Aphrodite of Knidos Statue – Analyzing This Female Sculpture

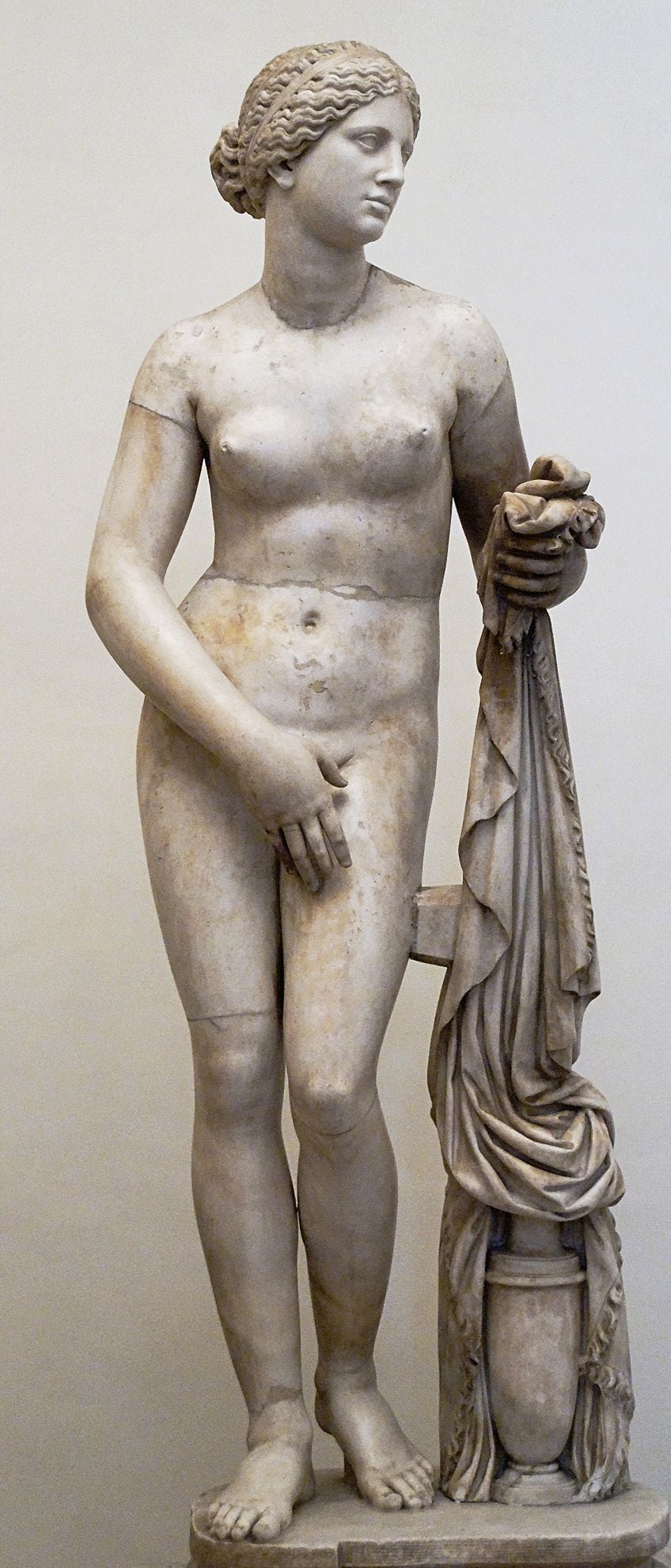

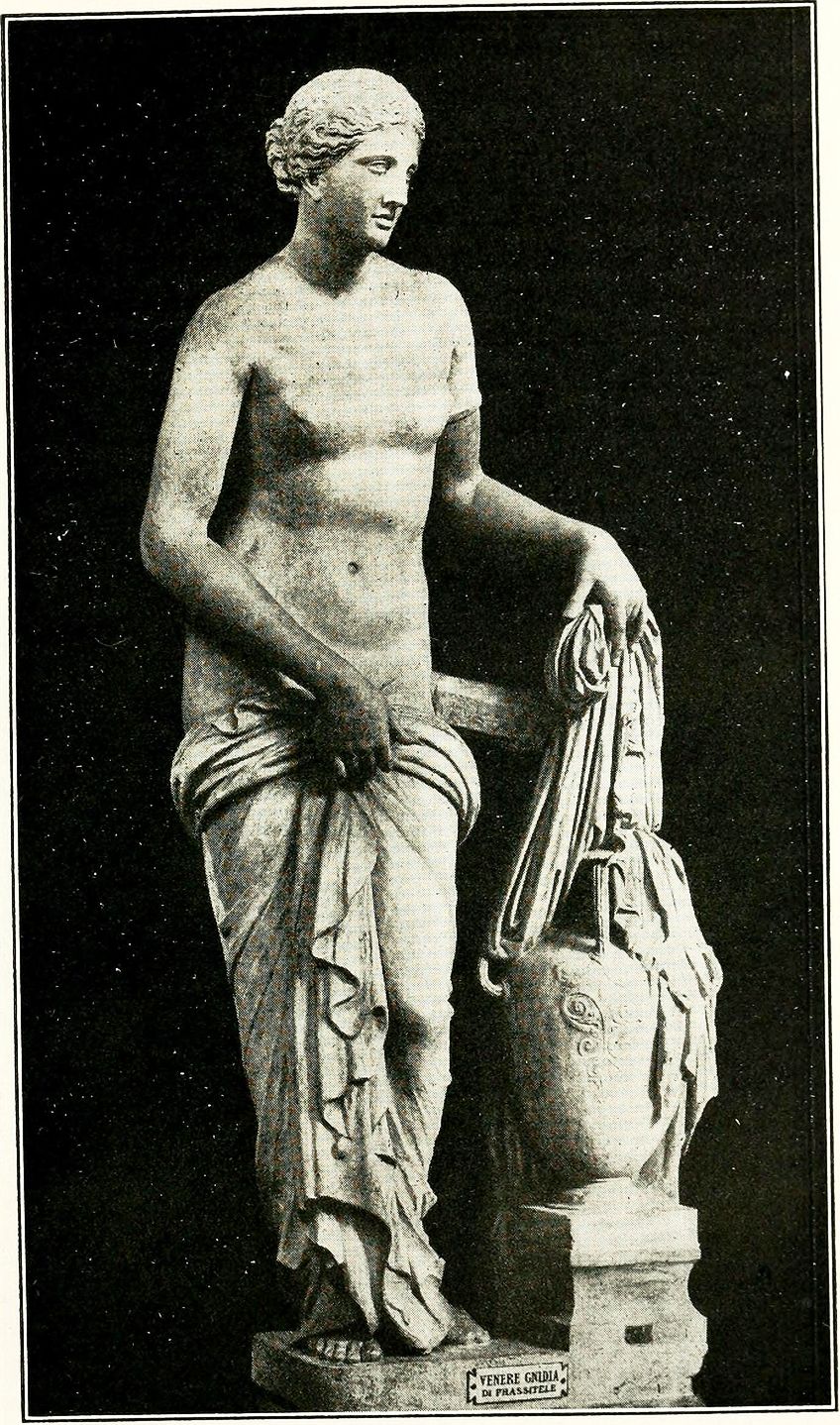

The Aphrodite of Knidos Statue is a sculpture of Aphrodite, a Greek Goddess. The Aphrodite sculpture is among the first female Greek and female Roman statues to be created in life-size. The Aphrodite body type was a unique representation of classical female sculpture in the era of the portrayal of heroic male nudes. The Aphrodite nude is portrayed reaching out for a bathing towel while modestly concealing her pubic area. Although the original Aphrodite statue has long been destroyed, there are many Roman copies of the Aphrodite nude.

Interesting Facts About the Aphrodite of Knidos Statue

The original Aphrodite statue was created for the Temple of Aphrodite at Knidos as a devotion monument. It represented the Goddess as she proceeded for the ceremonial bath that regenerated her pureness, shedding her drapery with one hand and discreetly concealing herself with the other. Her hands’ positioning obscures her pubic region while attracting attention to her bare upper body. The monument is famous for its beauty, and it is intended to be seen from every aspect.

| Sculptor | Praxiteles |

| Period | 4th Century BC |

| Style | Greek Late Classical |

| Dimensions | 205 cm |

The Original Aphrodite Statue

Because each copy has a distinct body form, attitude, and accessory, the prototype can only be characterized in broad strokes; the body twisted in a contrapposto posture, with the head possibly tilted to the left. Although Lucian stated that she “sported a faint smile that only exposed her teeth,” most later renditions do not include this.

Female kore figures were dressed approximately three centuries just after oldest naked male equivalents in Greek art, the kouros; the feminine kore figures were dressed. Previously, nakedness was a heroic costume reserved for males exclusively.

Heroic nudity provided a function for the male audience, bringing aesthetic pleasure to the observer, who was inherently masculine. Spivey claims that the Aphrodite of Knidos statue’s iconography may be credited to Praxiteles, who created the statue with the intention of being observed by male passersby.

The overwhelming evidence from assemblages shows that the Knidian artwork was intended to elicit male sexual reactions upon encountering the classical female sculpture, which were claimed to have been promoted by the temple attendants.

The sculpture of Aphrodite created a canon for female nudity proportions, inspiring several reproductions, the finest of which is believed to be the Colonna Knidia in the Pio-Clementine Museum of the Vatican. It is supposed to be a Roman replica, and it does not equal the polished brilliance of the original, which was burned in a terrible fire in Constantinople in CE 475.

Praxiteles sculpted both a naked and a clothed statue of Aphrodite, according to Pliny the Elder. The city of Kos bought the draped monument because they thought the naked version was obscene and reflected badly on their city, but the city of Knidos bought the naked statue. Pliny states that it gained Knidos prominence, and coins portraying the statue that were struck there appear to substantiate this.

Praxiteles was said to have utilized the prostitute Phryne as a subject for the sculpture, adding to the speculation over its origins. The statue became so well-known and replicated that the goddess Aphrodite personally traveled to Knidos to view it, according to a comical tale.

Antipater of Sidon’s lyric epigram sets a hypothetical query on the goddess’s lips: “Paris, Adonis, and Anchises saw me nude, that’s all I know, but how could Praxiteles concoct it?”

The Temple in Knidos

The Aphrodite sculpture, although being a religious figure and a patron of the Knidians, became a popular tourist destination. Nicomedes I offered to settle Knidos’ massive debts in return for the Aphrodite nude, but the Knidians declined. The sculpture of Aphrodite would have been polychromed and so lifelike that it stimulated men sexually, as evidenced by the legend of a young man breaking into the sanctuary at night and attempting to fornicate with the sculpture, leaving a stain on it.

An attendant priestess informed tourists that after he was found, he was so humiliated that he threw himself over a cliff at the temple’s edge. This narrative is told in the dialogue Erotes, which is typically assigned to Lucian of Samosata and contains the most detailed literary depiction of Aphrodite’s temenos at Knidos.

Erotes wrote, “The ground of the courtyard had not been condemned to sterility by a concrete surface, but had erupted with abundance, as Aphrodite would have wanted, […] To be honest, there are some unproductive trees among them, but their fruit is beautiful. […] Undoubtedly, Aphrodite is really only more appealing when joined with Bacchus; their joys are better since they are combined together.”

The narrator uses exaggeration to describe Aphrodite: “When we had drained the allure of these locations, we proceeded to the shrine itself. The goddess is seated in the middle, her statue fashioned of Paros marble. A high grin has her lips slightly parted. Except for a stealthy hand veiling her modesty, nothing covers her beauty, which is completely revealed. The sculptor’s craft has accomplished so brilliantly that it appears the marble has abandoned its hardness in order to form the elegance of her limbs.”

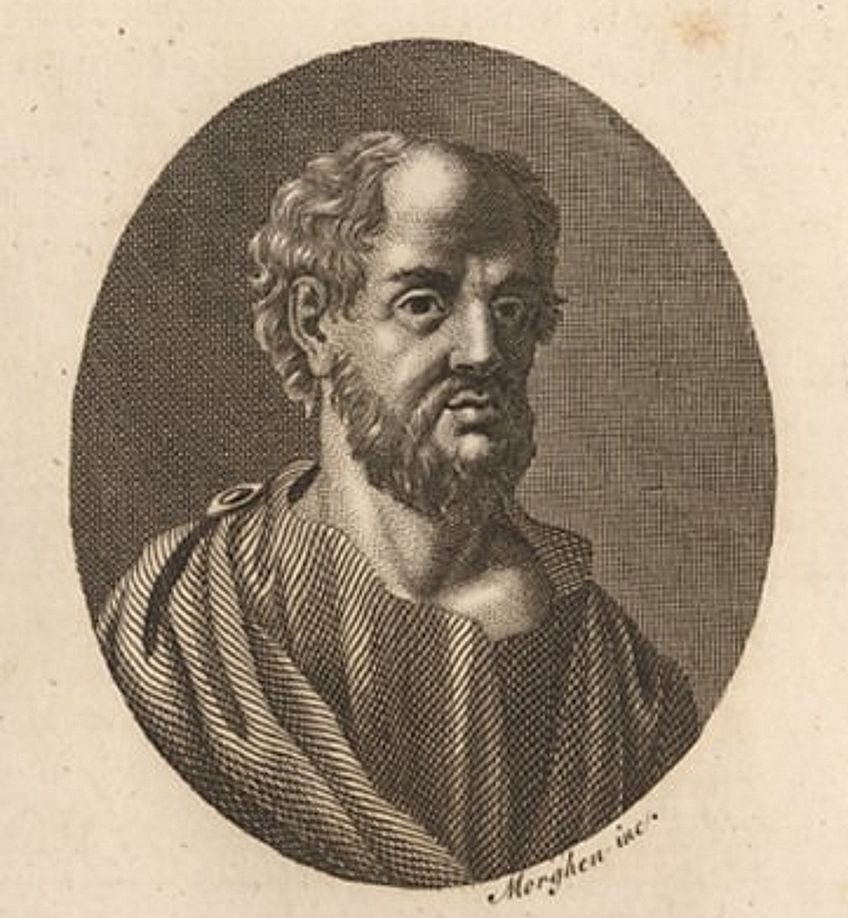

The Sculptor Praxiteles

Praxiteles of Athens, the son of Cephisodotus the Elder, was the most prominent sculptor in Attica during the fourth century BC. He was the first to build a life-size statue of a naked woman. While no sculpture ascribed to Praxiteles is known to exist, several replicas of his sculptures have remained; numerous historians, notably Pliny the Elder, reported about his creations; and coins engraved with silhouettes of his various notable statuary types from the period are still in existence.

A rumored romance between Praxiteles and his attractive muse, the Playwright harlot Phryne, has generated conjecture and reinterpretation in works spanning from paintings to comic opera to shadow play. Some writers have claimed that the name Praxiteles was used by two sculptors. One was a colleague of Pheidias, while the other was his better-known grandson.

Though it is usual in Greece for the same name to be repeated every other generation, there is no conclusive evidence supporting either stance.

Precise dates for Praxiteles are difficult to come by, but given the absence of proof that Alexander the Great employed Praxiteles, which he very certainly would have done, it is probable that he was no longer functioning. Pliny’s date, 364 BC, is most likely that of one of his greatest famous writings.

Praxiteles’ subjects were either humans or dignified and less aged deities like Apollo, Hermes, and Aphrodite instead of Zeus, Poseidon, or Themis. Praxiteles and his pupils nearly completely worked with Parian marble. At the time, the Paros marble quarries were at their peak, and no marble could be better for the needs of the artist than that from which the Hermes of Olympia was fashioned.

The Background of the Famous Aphrodite Sculpture

Greek and Roman writers constantly addressed the concept that the highest form of art was a complete imitation of actuality; or, to put it differently, that there’s no discernible difference between the picture and its original. The most famous narrative along these lines is two competitive painters Zeuxis and Parrhasios, who competed to see who was the more competent.

Zeuxis painted a group of grapes that looked so lifelike that birds swooped in to devour them.

It was an illusionary triumph that threatened to take the day. However, Parrhasios painted a curtain, which Zeuxis, thrilled with triumph, ordered he take aside to expose the artwork behind. Pliny, who related the episode in his encyclopedia, stated that Zeuxis swiftly recognized his error and relinquished victory, saying, “I tricked just the birds, Parrhasios misled me.”

There is no sign of any such artworks, assuming they even actually existed beyond the narrative. We do, however, have documentation for a marble sculpture that was the focus of a similar, but considerably more horrific, narrative. That is a sculpture created in 330 BCE by the artist Praxiteles, and it is today known as the “Aphrodite of Knidos statue,” after the Hellenic town on the western coast of modern-day Turkey where it first resided.

The Aphrodite sculpture was heralded as a breakthrough in artwork in antiquity because it was the first full nude sculpture among Greek and female Roman statues following millennia of sculptures of women, like Phrasikleia, being shown clothed. Praxiteles’ original Aphrodite statue has long been lost; one tale has it that it was finally transferred to Constantinople, where it was ruined in a blaze in the 5th century CE.

However, it was so popular that hundreds of variations and duplicates of it were manufactured across the classical civilizations, in full size and miniatures, and it even appeared as the design on coinage. Many of these variants have been preserved.

It is impossible to get beyond the prevalence of such pictures of the nude female form now and imagine how audacious and risky it would have been for the first spectators in the 4th century BCE, who was undoubtedly not accustomed to the prominent exhibition of feminine skin.

Even the phrase “first female nude” minimizes the significance by indicating that this was an artistic or aesthetic breakthrough that was just waiting to happen.

In reality, whatever was steering Praxiteles’ research (another “Greek Renaissance” whose causes we don’t truly comprehend), he was shattering traditional presumptions about craft and sexual identity in very much the same manner that Tracey Emin or Marcel Duchamp have done since: whether it’s actually turning a public urinal into an original artwork in the particular instance of Duchamp, or Emin’s tent. It’s hardly unexpected that the first client to whom the sculptor presented his new Aphrodite, the Greek town of Kos on an island off the Turkish coast, said, “No, thank you,” and chose a more conservatively clothed version instead.

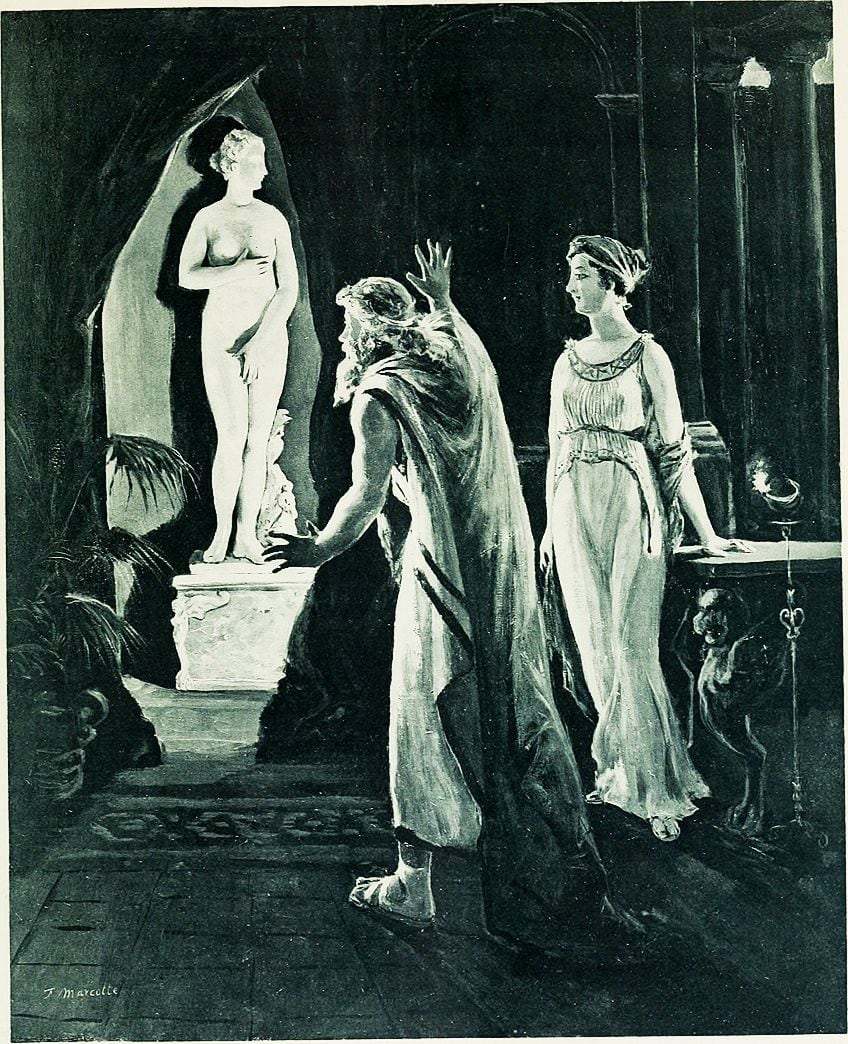

But being nude was only one aspect of it. This Aphrodite was unique in an erotic sense. The hands solely are a dead giveaway. Are they attempting to conceal her? Are they going in the path of what the spectator is most interested in seeing? Or are they just teasing us? Whatever the explanation, Praxiteles established an edgy interaction between a female statue and an imagined male spectator which has never been lost in the annals of European art—as certain early Greek audiences were all too cognizant. It was a feature of the sculpture that was dramatized in a fascinating story about a man who handled this famed goddess in marble as if it were a flesh and blood lady.

It is described in its entirety in a strange essay published about 300 CE.

The author describes what is probably definitely a fictitious dispute between three men – a monk, a heterosexual, and a homosexual – over which type of sex, if any, is ideal. During their journey, they arrive at Knidos and proceed to the town’s main attraction, the famed statue of Aphrodite in her temple. While the heterosexual is looking at her head and front, and the person who appreciates the love of boys is looking at her back, they notice a little flaw in the marble around the top of the statue’s thigh.

As an art aficionado, the monk begins to extol Praxiteles’ praises for hiding what may have been a defect in the stone in such an unobtrusive place – but the woman keeper of the temple pauses him to explain that something far eviler lurked behind the mark. She says that a young person once met and fell enamored with the sculpture and managed to lock himself in with her for the entire night and that the small stain is the sole remaining proof of his lust.

Both the heterosexual and homosexual say that this validates their thesis, with one commenting that even a lady in stone may stir passion, and the other claiming that the placement of the stain indicates that she was taken from behind, like a boy. The caretaker, on the other hand, insists on the terrible sequel: the young guy went insane and hurled himself off a cliff.

This narrative has a number of difficult lessons. It is a reminder of how unsettling some of the ramifications of the Greek Revolution may be, how enticing it is to blur the line between life-like stone and real-life humanity, and how hazardous and foolish it is to do so. It demonstrates how a feminine statue may drive a guy insane, but also how art can serve as an explanation for what was, after all, rape. Remember, Aphrodite never agreed.

This has been our look at a few of the interesting facts about the Aphrodite sculpture. The Aphrodite sculpture is among the first female Greek and female Roman statues to be created in life-size. “Aphrodite of Knidos” statue is a sculpture of Aphrodite, a Greek Goddess. The Aphrodite body type was a unique representation of classical female sculpture in the era of the portrayal of heroic male nudes. The Aphrodite nude is portrayed reaching out for a bathing towel while modestly concealing her pubic area. Although the original Aphrodite statue has long been destroyed, there are many Roman copies of the Aphrodite nude.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Does the Original Aphrodite Statue Come From?

The original Greek classical female sculpture was made. The Aphrodite sculpture established a standard for female nudity dimensions, prompting several copies. Praxiteles was claimed to have used the prostitute Phryne as a model for the sculpture, adding to the mystery surrounding its beginnings. According to Greek legend, the statue became so well-known and copied that the goddess Aphrodite personally visited Knidos to see it.

What Was So Special About the Aphrodite Sculpture?

This statue was so popular that hundreds of modifications and replicas were produced throughout the classical civilizations, in full size and miniatures, and it even featured as the design on coins. Many of these varieties have survived. It is tough to look past the current abundance of such images of the naked female form and fathom how daring and perilous it would have been for the initial viewers in the 4th century BCE, who were surely used to the prominent display of feminine flesh. Even the phrase first female nude downplays the significance by implying that this was a mere creative or aesthetic breakthrough waiting to happen.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Aphrodite of Knidos Statue – Analyzing This Female Sculpture.” Art in Context. January 13, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/aphrodite-of-knidos-statue/

Meyer, I. (2022, 13 January). Aphrodite of Knidos Statue – Analyzing This Female Sculpture. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/aphrodite-of-knidos-statue/

Meyer, Isabella. “Aphrodite of Knidos Statue – Analyzing This Female Sculpture.” Art in Context, January 13, 2022. https://artincontext.org/aphrodite-of-knidos-statue/.