Monet Japanese Bridge – A Walk Across Monet’s Famous Bridge Painting

The Impressionist painter Claude Monet painted a few bridges in his day – perhaps you remember his famous Waterloo Bridge series of the 1900s? But there was another bridge that led right into and from the artist’s heart, and that was his Japanese bridge from his famous waterlily garden. This article will explore the Japanese bridge Monet painted during his flourishing years in Giverny.

Artist Abstract: Who Was Claude Monet?

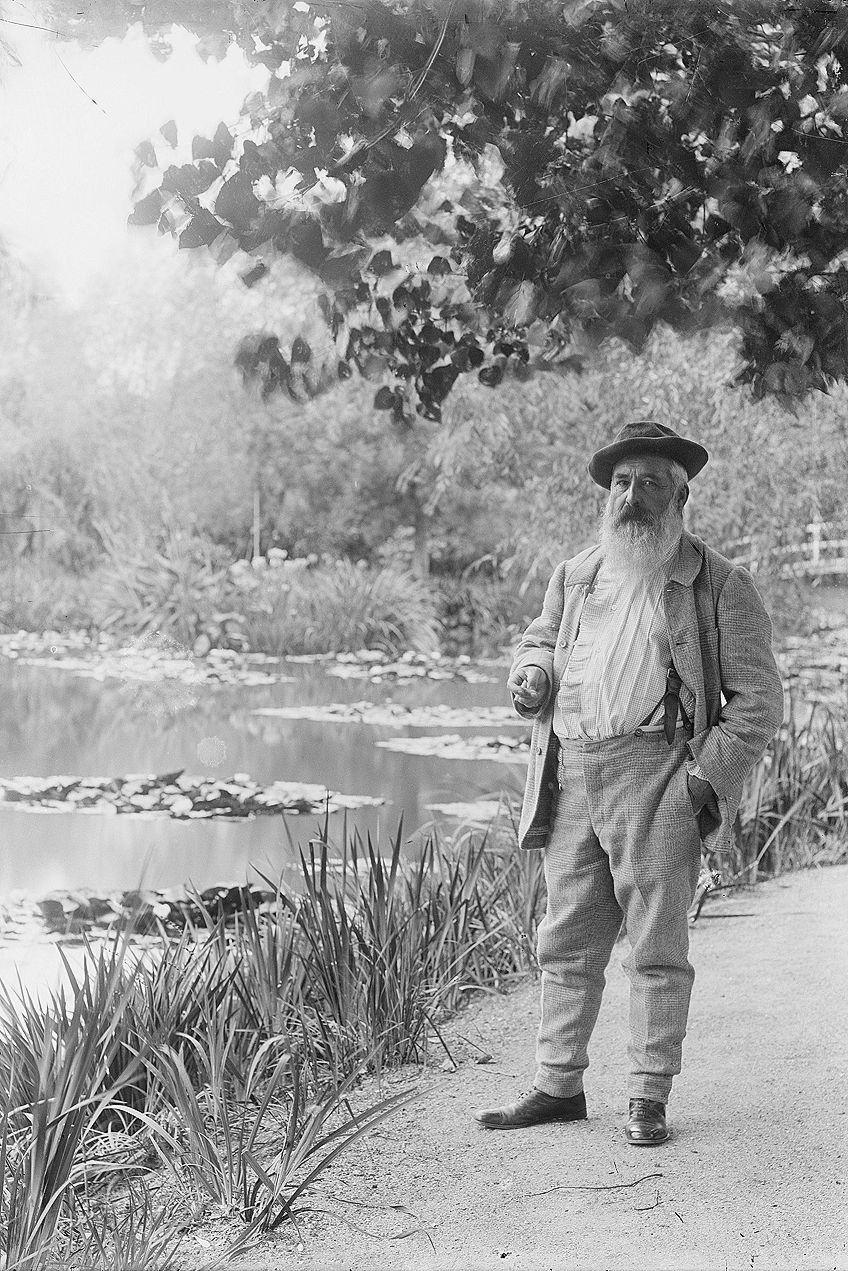

Claude Monet, born 14 November 1840 in Paris, was one of the most prolific Impressionist painters during the 19th Century. He started working as an artist at around 15 years old, selling various portraits. He studied in Paris at the art school Académie Suisse and served in the military, which took him all the way to Algeria where he would be significantly artistically influenced. Monet was acquainted with many other artists of the time, namely Édouard Manet and Camille Pissarro. It was Monet’s painting, Impression, Sunrise (1872), which inspired the name for the art movement Impressionism.

Monet’s Japanese Bridge in Context

Below, we will discuss one of Monet’s iconic oil paintings, The Japanese Footbridge (1899) in addition to many other iterations of the same structure. First, we will provide a contextual analysis, going over some of the social, historical, and cultural factors that shaped Monet’s life at the time. Secondly, we will provide a more formal analysis, looking at Monet’s stylistic approaches.

| Artist | Claude Monet |

| Date Painted | 1899 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Genre | Landscape |

| Dimensions | 81.3 x 101.6 centimeters |

| Series | Water Lily Series |

| Where Is It housed? | National Gallery of Art |

| What Is It Worth? | The painting has been estimated to be worth between $50 million and $150 million dollars. |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

It all started when Monet moved to Giverny with his family in 1883. Giverny is a village located in the northern parts of France, near the banks of the River Seine in Normandy. What prompted Monet to move to Giverny was his view of the village while on a train trip. Monet fell in love with the small village and made the decision to live there, so he rented a home and bought it years later. The home was located on what used to be a cider farm.

During his life at Giverny, Monet set out to create a lush garden. In 1893, he located some land close by to his home. The land had a pond that the artist converted into a water garden, which was inspired and influenced by the Japanese style. Monet’s new home and garden became a significant, in fact, primary, source of inspiration for his artistic career.

He was deeply moved by the natural surroundings he created, and he is quoted endearingly describing his garden, saying:

“My garden is my most beautiful masterpiece. I work at my garden all the time and with love. What I need most are flowers. Always. My heart is forever in Giverny, perhaps I owe it to the flowers that I became a painter.”

The artist was also a horticulturist and worked on expanding his water garden. Eventually, he managed to divert water from the Epte River and include various types of trees, bushes, an assortment of flowers, and exotic plants. It is also said that Monet’s water lilies were imported from South America and Egypt.

Most notably were the above-mentioned famous water lilies, which became the main subject matter for his series of paintings called the Water Lily series (also Nymphéas), with around 250 paintings all exploring and depicting various aspects of the famous and beloved water garden. Another important addition to Monet’s garden was the wooden bridge included in 1895, built in a Japanese style that reached across the pond.

Formal Analysis: A Look at Monet’s Style

There are 12 iterations of the Japanese bridge Monet painted, all exploring his water garden from different “views”. It is important to note that Monet’s paintings vary slightly in their composition, and some are housed in different museums and art galleries. In this article, we will mostly refer to The Japanese Footbridge, painted in 1899, which is now housed in the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. in the United States, while mentioning other paintings within the series for more context.

Art history sources report that Monet would visit his garden a few times a day and observe the changing of the light and seasons, which would affect the way he portrayed each painting in his series.

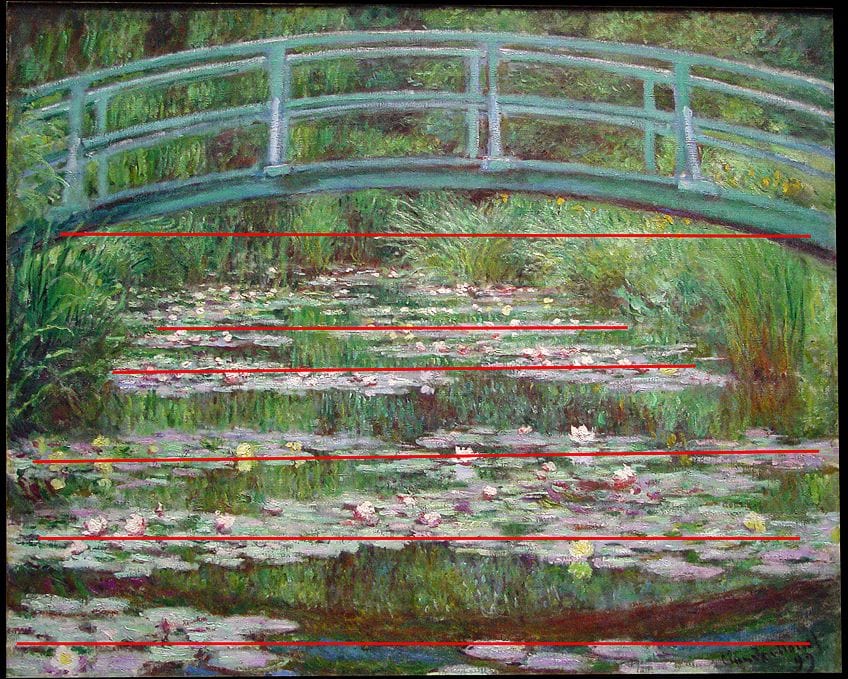

When we look at The Japanese Bridge specifically, which you can see above, we will notice a vertical composition consisting of the arched bridge towards the upper part of the painting, leaving minimal space between the top edge of the painting and the upper part of the bridge, thus creating a kind of border along with the entire upper third of the canvas.

This is not the only manner Monet painted it, however. In various other iterations, such as Water Lilies and Japanese Bridge (1899), housed at the Princeton University Art Museum, there is space between the top of the painting and the bridge, giving us a different “feel” for the composition.

Below the famous bridge, we see the water pond with an assortment of pink water lilies here and there, and the surrounding lush, green foliage that makes up most of the background, also predominantly along with the top third of the painting. The forefront of the painting depicts mostly the water, almost as if Monet took a snapshot of a moment in time – the painting becomes almost like a continuation of the actual water pond.

On the lower third of the painting, there is a slight indication of the bridge’s reflection in the water, although this mirrored effect does not steal away any of the glory from the real bridge above.

Color

In terms of the colors in this oil painting, Monet did not include any stark colors; instead, we are met with cool and warm tones. There is the dominance of greens from the surrounding foliage and blues from the bridge, and what gently appears to be a patch of sky through the trees in the background, which together all add a cool and calming effect to the painting. Interspersed are warmer tones that color the water lilies – many appear pink with hints of yellow. There is a combination of whites that suggests areas where light reflects.

This painting is a typical example of an Impressionist painting because it is painted outside, a term referred to as en plein air in French, meaning “outdoors”. It simply means to paint outside, a common stylistic trait of Impressionism. Artists sought to paint outside so as to capture the natural light as opposed to the artificial light found inside in a studio.

Impressionists also painted with a light background to prime their canvas, which further enhanced the element of brightness within the overall painting.

We do not notice a strong emphasis on darker backgrounds, nor do we see large areas of darker colors like blacks or browns in this famous bridge painting, as well as in many of Monet’s (and other Impressionist’s) paintings. The only area that suggests darker hues can be seen near the background in the foliage, as well as darker reds from the bridge’s reflection and patches in-between areas of foliage to suggest shadow.

A characteristic of Impressionist artists was that they utilized colors from the light spectrum (red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo, and violet) with mixes of white, which we notice in most of Monet’s Japanese bridge paintings.

Furthermore, many artists utilized colors in a complementary way, placing certain colors next to the other to enhance their vibrancy.

It should be noted that although the earlier paintings of Monet’s famous Water Lily series appeared calm and tranquil in their lighter colors, some of Monet’s later paintings incorporated darker colors due to his eyesight being affected by cataracts. He started utilizing darker reds, oranges, and other earthy colors.

Texture

The texture of Monet’s brushwork consists of short brushstrokes and is often described as “rapid” or “choppy”. They are done in horizontal and vertical strokes, delineating the water lilies on the pond and the verticality from the surrounding grassy foliage and its reflection in the water. We also notice dabs or blotches of paint on the water lilies, a technique referred to as tache in French, which means “mark” or “stain”.

There is also a fluidity in Monet’s brushwork that indicates a looseness in the foliage swaying in the wind. Viewing the painting from a closer vantage point, it appears as if the brushstrokes are applied with a sense of ease and freedom, a colorful assortment of short, long, thick, and thinly applied paint, which, when all combined, creates the full picture we see when viewing it from afar.

Monet also received criticism for his paintings. Many described his works as unfinished and that he did not adhere to traditional methods of painting. Some critics also mentioned that his work did not have enough detail.

As for Monet’s later paintings within his series, such as The Japanese Footbridge (1920 to 1922), housed in the Museum of Modern Art in New York, we notice the brushstrokes are looser and applied in thicker strokes of paint, quite haphazardly; it is almost as if the painting depicts a raging fire. This, again, was due to Monet’s failing eyesight.

Line

There is an interplay of horizontal and vertical lines in this composition. We will notice the water from the pond almost receding into the background with the utilization of linear perspective, creating a strong sense of verticality in the painting, moving towards an unknown point in the distance. This is intersected by the horizontal line created by the bridge from one end of the width of the painting to the other end. Furthermore, if we look at the dispersal of water lilies on the surface of the pond, these echo the horizontality from the bridge.

Besides the vertical and horizontal aspects in the artwork, we also notice short diagonal and curved lines from the foliage on the sides, as if these create a bordering or welcoming effect for the large expanse of water and the floating pink lilies. The bridge is also depicted as a curved shape crossing the width of the canvas, with its structural supports becoming curved rectangular shapes amidst the more naturally occurring environment.

Space

When we look at the space utilized in the composition, it comes from a natural observation of the environment. It does not seem to subscribe to the formal spatial requirements of art from other periods like the Renaissance and Neoclassicism, where artists paid particular attention to balance and harmony of where and how shapes and forms would be placed – think of paintings like Masaccio’s Tribute Money (c. 1425) or Oath of the Horatii (1786) by Jacques-Louis David.

The space in Monet’s Japanese bridge paintings, and really most of the Water Lily series, is characteristically Impressionist. Impressionist artists depicted their subject matter in a real manner, where sometimes figures or objects would be cut-off or not completely centralized in the picture plane.

Similarly, when we look at Monet’s famous bridge painting, although there are no human or animal figures present, the natural environment is depicted in such a way that it is almost like a moment in time, and we do not see the full bridge from end to end.

Some areas will appear “cut-off”, for example, we also do not see where the water begins. It merely flows into our space from an unknown source, but it is as natural a pictorial space as the natural environment itself.

In other paintings of Monet’s Japanese bridge, for example, The Japanese Bridge (1900) housed in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, we will see a path leading to the bridge on the left side of the composition. This gives us an entirely new vantage point of the bridge as well as showing us more context in terms of what the rest of Monet’s garden looked like.

In numerous other iterations of the famous bridge painting, such as an earlier version entitled The Japanese Bridge (1896), housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Monet included more spatial awareness in the composition. We also see the path to the left leading to the bridge and the background appears more open compared to the lush greenery in later depictions.

Several of his later versions, namely, The Lily Pond, Green Harmony (1898), housed in the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, The Lily Pond (1899), housed in the National Gallery in London, and Bridge Over the Lily Pond (1899), housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, all depict a more focused perspective of the bridge without any of the surrounds.

The space may even seem more “cramped” from the lush greenery, making up the background like a backdrop with the water pond and bridge becoming the main focal points.

In Monet’s other paintings, we also see views of the bridge from the left side, as in Water Lily Pond (1900) at the Art Institute of Chicago, Water-Lily Pond, Symphony in Rose (1900) at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, and The Water-Lily Pond (1900) at the Museum of Fine Art in Boston.

Scale

Monet’s Water Lily series is a large scale, as we see from the series in Paris at the Musée de l’Orangerie, which covers an oval-shaped wall space and is 90 meters long. If we look at the famous bridge painting mentioned in this article, it measures 81.3 by 101.6 centimeters and shows the full depiction of the famous Japanese bridge and surrounding water lilies.

Many of Monet’s paintings ranged in dimensions, some measuring 200 by 200 centimeters and others 89 by 92 centimeters.

As Monet grew older, his paintings became more abstract and his compositional scale (the size of the subject matter in the painting) changed by focusing on specific areas of his garden. We can see this in the Water Lily from the Musée de l’Orangerie where it is only depictions of the water lilies on an expanse of water and not the full view of the bridge and water lilies scene. Another example of this “close-up” view includes Water Lilies (1906), which is housed in the Art Institute of Chicago.

Interesting Facts About the Monet Japanese Bridge

When Monet set out to build his water garden and bridge, he received resistance from the local community. However, he eventually got permission and set out to build what was to be a great source of inspiration not only for Monet but also for the many other artists who succeeded him.

Some sources also say that if it was not for the local community’s approval, Monet would not have produced his series of iconic water lilies and Japanese bridge paintings.

The Japanese culture influenced Monet’s style, inspiring him to introduce various Japanese motifs and elements such as the Japanese bridge. Monet was a collector of Japanese woodblock prints called Ukiyo-e, which means “pictures of the floating world” in Japanese.

This style of art was a great source of inspiration for the Impressionist artist. It also inspired many other Impressionist artists and was termed as Japonisme by the French critic Philippe Burty in 1874. This Japonsim also influenced artists from succeeding art movements like Post-Impressionism.

Forever in Giverny

Monet passed away in December of 1926 and continued living in Giverny until his death. His life at Giverny gave him tremendous success in his artistic career. Today, his home and garden at Giverny are run and maintained by the non-profit organization called Fondation Claude Monet, which opened the house to visitors during 1980. It has become one of the most frequently visited sites in the art world.

Each Monet Japanese bridge painting is unique, telling us a different story through its visual vibrancy of colors, brushstrokes, and verdant landscape of flowers, foliage, and decorative bridges. Each painting also shows us how Monet played with the concept of light (especially its many reflections on the water pond) and how colors can show us reflections of a truer nature around us.

Monet’s Water Lily series paintings, including his series of famous bridge paintings, are true testaments to this artist’s skill, paving the way for the evolution of Impressionism and other art movements thereafter. If Monet took the same number of photographs of his beloved water garden, these would not do it justice the way his paintings did.

Take a look at our Japanese Bridge Monet painting webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

When Did Claude Monet Paint the Japanese Bridge?

Monet started painting his famous Japanese bridge during his time living in the village of Giverny. In 1899, he painted The Japanese Footbridge along with 12 other different views of the same bridge. The different versions are all housed in different art galleries and art museums around the world.

Is Monet’s Japanese Bridge Part of a Series?

Monet’s Japanese bridge paintings are part of his Water Lily series (also called Nymphéas). There are around 250 oil paintings that show various aspects of his water garden in Giverny. Another important addition to Monet’s water garden was the Japanese-style wooden bridge, included in 1895, which was built to go across his pond.

Why Is Monet’s Water Lily Series So Popular?

Monet’s series of water lily paintings, including the Japanese bridge, has been considered as some of the artist’s best artwork from his painting career. He skilfully explored the nature of color and light in his compositions and he depicted the natural environment in a new way that would influence the art world for years to come.

What Techniques Did Monet Use in His Japanese Bridge Paintings?

As an Impressionist painter, Monet utilized several techniques that explored the way light was depicted in the natural environment. One of his primary techniques (and style) is painting outside, referred to as en plein air in French, meaning “outdoors”. Monet’s brushwork would often consist of short brushstrokes with dabs or blotches of paint to depict the water lilies, a technique called tache in French, which means “mark” or “stain”.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Monet Japanese Bridge – A Walk Across Monet’s Famous Bridge Painting.” Art in Context. August 9, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/monet-japanese-bridge/

Meyer, I. (2021, 9 August). Monet Japanese Bridge – A Walk Across Monet’s Famous Bridge Painting. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/monet-japanese-bridge/

Meyer, Isabella. “Monet Japanese Bridge – A Walk Across Monet’s Famous Bridge Painting.” Art in Context, August 9, 2021. https://artincontext.org/monet-japanese-bridge/.