Max Beckmann – Taking a Look at Max Beckmann’s Artworks and Legacy

Max Beckmann’s drawings transformed his observations of modern society into evocative visuals that disturb the observer with their emotional complexity and meaning. Max Beckmann’s paintings were linked to the New Objectivity movement and served as caustic visual criticisms of the turbulent interwar years. In later years, Max Beckmann’s artworks aimed for open-ended narratives that mixed scenes from life, fantasies, mythology, and dreams. Throughout his lifetime, he resisted the trend toward abstract artworks and remained committed to capturing the enchantment of reality and transferring it to canvas.

Max Beckmann’s Biography

| Nationality | German |

| Date of Birth | 21 February 1884 |

| Date of Death | 27 December 1950 |

| Place of Birth | Leipzig, Germany |

Max Beckmann’s mastery of gently layering people and symbols, as well as hue and shadows, enabled him to skillfully transform his experience into compelling dramatic canvases throughout his long career. During World War I, the future artist served as a medical officer, an event that prompted a significant transition in his creative approach from a conventional, academic manner to a more socially informed and emotive painting style.

Throughout his career, he expertly mixed allegorical characters and real-life scenes in semiotically charged artworks that expressed his own take on the cultural, societal, and political situation.

Childhood and Early Training

Max Beckmann was always interested in painting, and he would frequently disturb class by sketching and sharing them around. Beckmann’s oldest self-portrait comes from roughly 1898 when he was still a teenager, and it displays his early commitment to the visual arts.

He was determined to pursue a career in painting and, over his family’s objections, applied to the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts in 1898, but was denied admission.

Beckmann enrolled at the Grand Ducal Art Academy in 1900, notwithstanding the initial standstill in Dresden. Carl Frithjof Smith, a Norwegian realism artist who established in Beckmann a passion for accurate portrayal of truth, was his primary teacher. In 1902, he received an honorary diploma from the academy, and the next year, he embarked on the first of many travels to Paris. He saw the art of the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists personally when he was there. Paul Cézanne’s works, particularly, left an indelible influence on him.

In 1904, he returned to Germany and settled in Berlin, where he remained until the outbreak of World War I. The light palette and precise placement of characters inside the picture plane in works from this early time reflect the effect of his Paris tour on his art. Beckmann got a six-month stay in Florence thanks to a grant from the German Artists’ League. Beckmann gained an appreciation for Friedrich Nietzsche’s philosophy and Edvard Munch’s dramatic techniques while overseas, and his work evolved into an Expressionistic style.

In 1906, he exhibited for the first time with the Berlin Secession, a group of youthful painters who formed to oppose the more traditional state-run art establishment.

Beckmann wedded Minna Tube, a female artist whom he had pursued while at the Weimar Academy, in the autumn of 1906. Beckmann also established a working contact with Paul Cassirer, a famous contemporary art dealer in Berlin in the same year. Cassirer organized a significant solo exhibit of Beckmann’s art in 1913, as well as published the first monograph on him. Large narrative sequences characterized his art throughout this period.

Beckmann purposefully situated himself in contrast to the abstraction promoted by Der Blaue Reiter painters like Franz Marc by depicting the external reality as he saw it. At the outbreak of World War I in 1914, Beckmann enrolled in the military. He served as a medical assistant in numerous hospitals until 1915 when he was dismissed due to a mental collapse on the Belgian front. He relocated to Frankfurt and continued his creative endeavors.

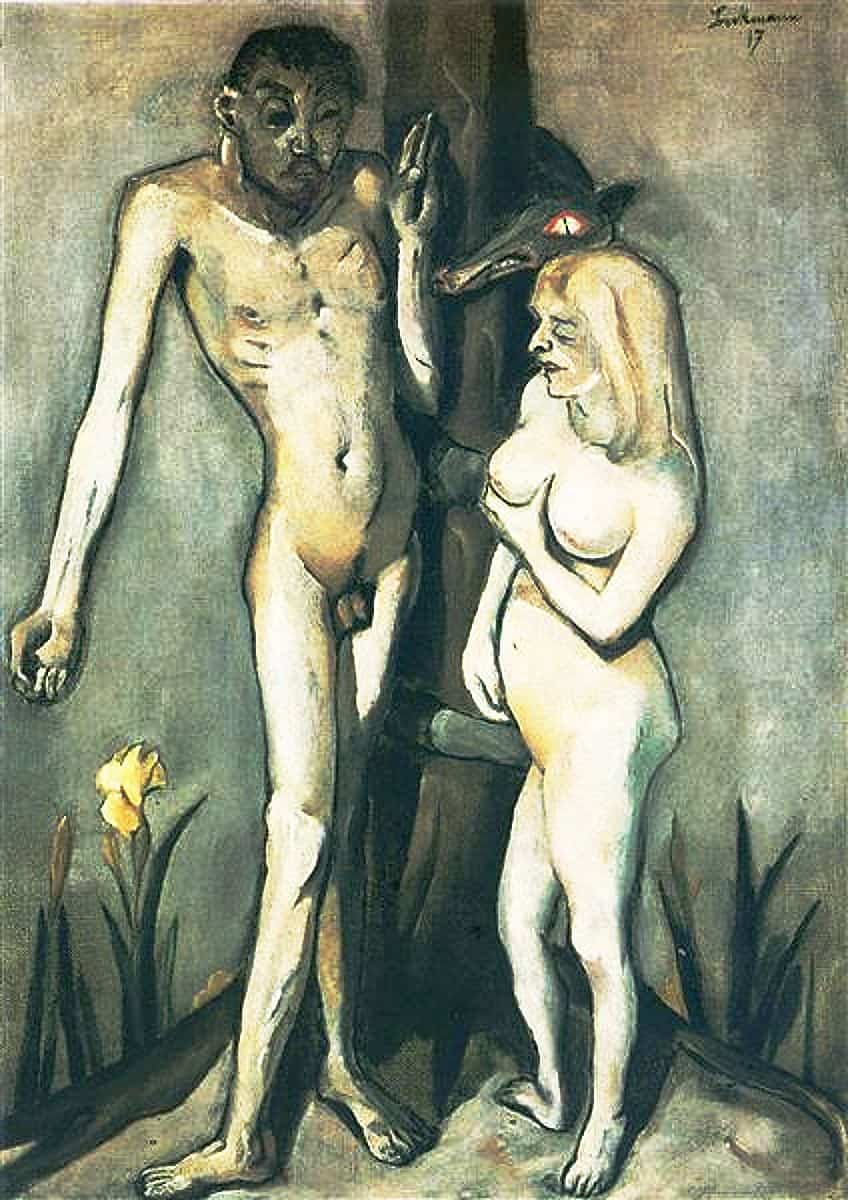

As evidenced in the ungainly, contorted figures of Adam and Eve (1917), one of the first works done after his rehabilitation following duty, his recollections of death and brutality during the war had a tremendous influence on his work.

Critics were critical of Beckmann’s latest style, which featured heavy, extended lines and cramped space.

Mature Period

Beckmann produced a manifesto in August 1918, in which he defined his views on the current upheaval and stated his resolve to “be part of all the agony that is coming.” He regularly utilized his work to interact with postwar Germany’s social, political, and economic challenges, notably in the setting of the New Objectivity movement, which severely highlighted Germany’s fragility following World War I.

Beckmann was widely regarded as one of the group’s pioneers, and he was extensively included in Gustav Hartlaub’s 1925 survey show at the Kunsthalle Mannheim.

Following the war, Beckmann and Tube split up and finally divorced peacefully in 1925. In the same year, he wedded Mathilde von Kaulbach, a youthful opera soprano, and acquired a teaching job at Frankfurt’s Stadel Art School. Max Beckmann’s artworks were often included in exhibits throughout Europe during the 1920s, including a huge retrospect in 1928 at the Stadtische Kunsthalle. By this time, he had refined his approach, using aspects from earlier works but in more vibrant, expressive hues.

In 1926, Neumann financed his debut show in the United States, and six of Max Beckmann’s paintings were featured in a new exhibit in 1931 in New York, organized by Alfred Barr. Following Hitler’s inauguration as Germany’s chancellor in 1933, Beckmann was dismissed from the Stadel School, and his works were confiscated from German institutions. In the same year, he left Frankfurt and moved to Berlin.

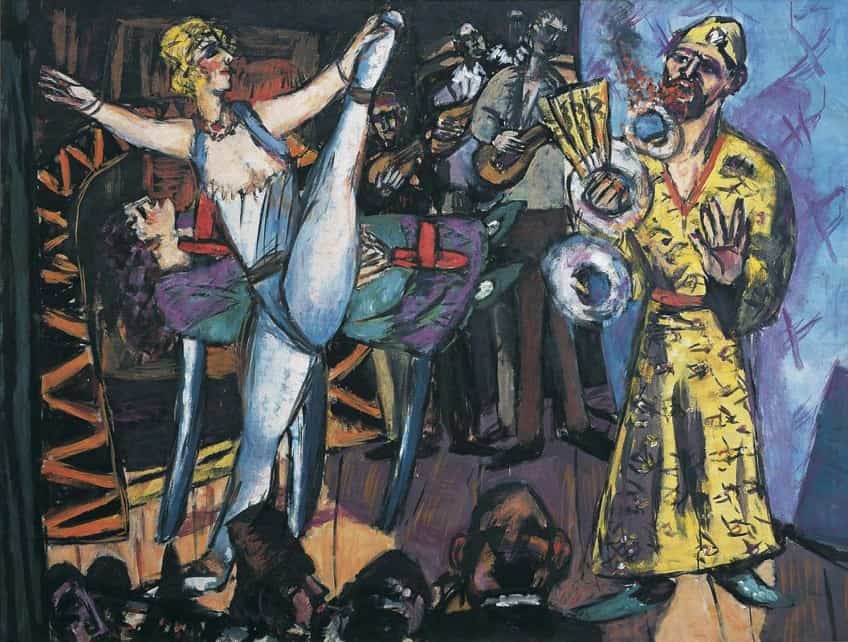

“Departure” (1937), the first of Beckmann’s famous triptychs, was made in the middle of an escalating conflict climate toward contemporary art in Germany.

Beckmann and his wife arrived in Amsterdam the same year, on the same day as the Nazi-sponsored Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich, which denigrated contemporary art. He would never return to Germany and spent the rest of his life abroad.

Later Years and Death

Beckmann stayed in Amsterdam during the war and produced a large number of canvases, prints, and sketches despite his relocation. In August 1947, he was offered a teaching job at Washington University’s School of Fine Arts in St. Louis. Beckmann arrived in St. Louis later that year after traversing the Atlantic with his wife.

He lectured in Oakland, Boulder, California, and Colorado, over the summers, and took use of the chance to visit the American country. When he was given a job on the staff of the Brooklyn Museum Art School in 1949, he departed St. Louis. That September, he and his wife relocated to New York City.

Max Beckmann passed away of a heart attack while heading to the Metropolitan Museum of Art to view his work on exhibit in December 1950.

The Legacy of Max Beckmann

Beckmann’s remarkable creative progress throughout two World Wars has left an indelible mark. His emphasis on the relevance of his own experience as a teacher was an enduring message for his pupils in both Europe and America. Beckmann’s close closeness to many different artists during his career provided for the flow of ideas among peers outside of his classroom instruction.

Some of Beckmann’s early contemporaries, such as Otto Dix and George Grosz, were influenced by his work.

These artists exchanged political and artistic ideas, each having a long-term influence on the others. Beckmann had a long and far-reaching effect as a teacher of young painters in America. Ellsworth Kelly was one of his students and recognized an aesthetic obligation to his professor in a catalog article decades later, despite stylistic differences. Even though Beckmann took over as an art professor at Washington University from Philip Guston, Guston benefited much from the German expatriate’s sensual use of color and strong narrative approach.

Beckmann’s paintings’ reputation in American museum collections boosted his influence on following generations of painters. Portraitists working in the late 20th century, such as Alice Neel, were influenced by Beckmann’s unflinching depictions of sitters, notably in terms of his use of harsh edges, brilliant colors, and candid portraits of his subjects.

The expressive style of Max Beckmann’s paintings, as well as his concern in critically expressing the realities of his period in painting, owe a debt to socially aware painters like William Kentridge and Leon Golub.

Important Examples of Max Beckmann’s Artworks

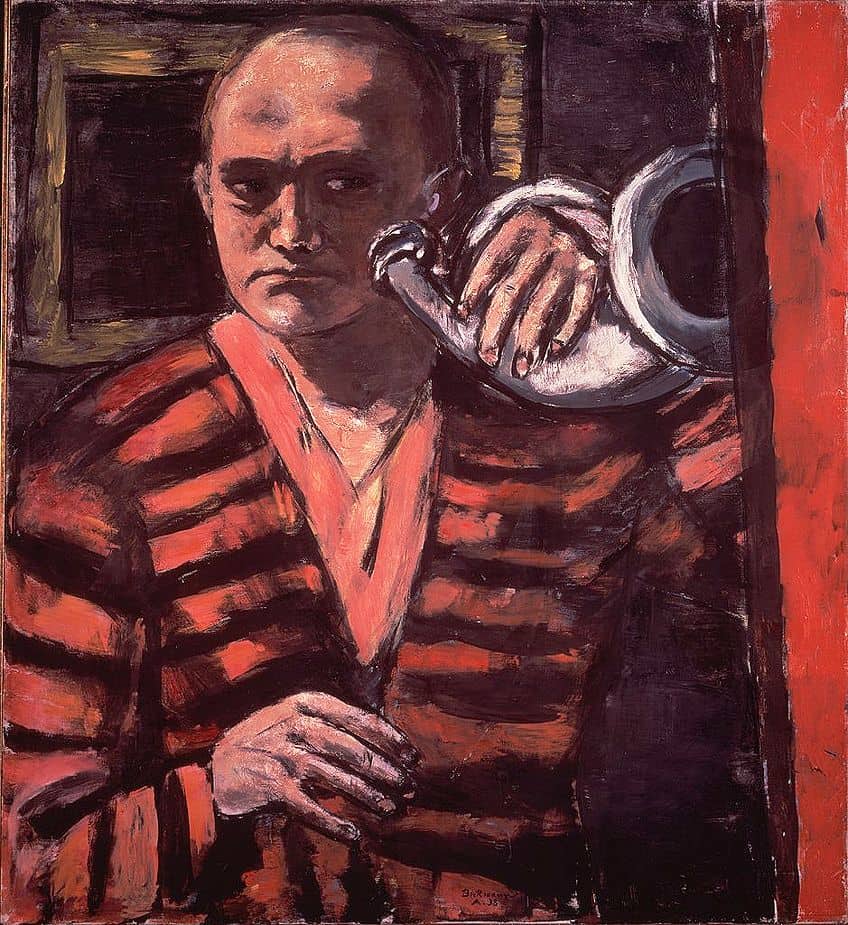

Beckmann was obsessed with gaining a complete understanding of himself, and to do so, he created over 85 self-portraits in a range of media. His lifelong conviction in the value of artists’ individuality and ideas of the world was underscored by his continual development of self-representation.

Beckmann dabbled in the triptych, or three-paneled painting, format. He transformed the out-of-date format, which had hitherto only been utilized for medieval religious artworks, into the right backdrop for his modern humanist parables.

Young Men by the Sea (1905)

| Date Completed | 1905 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 148 cm x 235 cm |

| Current Location | Schlossmuseum, Klasik Stiftung Weimar |

This artwork, created when he was just 21, exhibits the young artist’s strong intellectual background and deep visual awareness of the human form. He included multiple nudes in a variety of stances across the composition on this big canvas, giving the piece the illusion of a sophisticated anatomical study. The structure and subject pay homage to post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne, whose works Beckmann had seen the year before while in France.

The artwork’s illusionistic environment, large canvas size, and majesty of the characters all connect it to the academic style.

Beckmann’s mature, distinctive style, which distinguishes his later works, was yet to be deciphered. Despite the conventional nature of the job, Beckmann was able to link his education to his passion for the water. The expanse of the waters both impressed and alarmed him, and he countered the boundless emptiness of the horizon with a plethora of traditional characters in the foreground.

This traditional artwork was highly regarded in Germany’s academies and institutions. Beckmann was not only awarded the Villa Romana Award for this piece but it was also purchased by the Weimar Museum the next year.

Despite his initial success, Beckmann subsequently transitioned to a more expressive style that was more adapted to the dramatic topics he wanted to represent.

Adam and Eve (1917)

| Date Completed | 1917 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 57 cm x 80 cm |

| Current Location | Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin |

It’s one of the earliest paintings he finished following World War I, and it has little relation to his prewar vistas or large-scale tales. The painting is mostly bereft of color, rather being occupied by a range of grays that give the piece an overall tone of sorrow and create a thin spatial depth.

Beckmann’s turn towards moralizing pictures, in which every aspect, even the color of the paint, has a deeper significance, is also reflected in the muddy tones.

The yellow lily’s vivid pop and the serpent’s crimson eye contrast dramatically with Beckmann’s dismal palette for the flat terrain and skeletal humans, calling the audience’s eye to them right away. Beckmann’s affinity for symbolism and metaphor is evident in these images; the lily alludes to innocence and salvation, while the flaming red of the serpent’s eye highlights the devil’s mercurial nature. The two symbols neatly depict the consequences of man’s fall, cycling from sinfulness to salvation.

Aside from the artwork’s tonally symbolic structure, Beckmann’s integration of a range of elements resulted in jagged contours, flat color planes, and small space. The gruesome, twisted forms owe their existence to medieval German painters who depicted anguish and misery in similar ways. The Neue Sachlichkeit’s desire to resurrect German heritage in the face of modernity is exemplified by its use of medieval techniques and subject matter.

In contrast to the medieval influence, the Cubists’ compacted compositions impact the arrangement of space on the canvas, while the scathing tone of the portrayal is linked to the Expressionists’ social commentary.

Beckmann’s blending of these many tendencies led to the development of an individual style and the start of his most prosperous time.

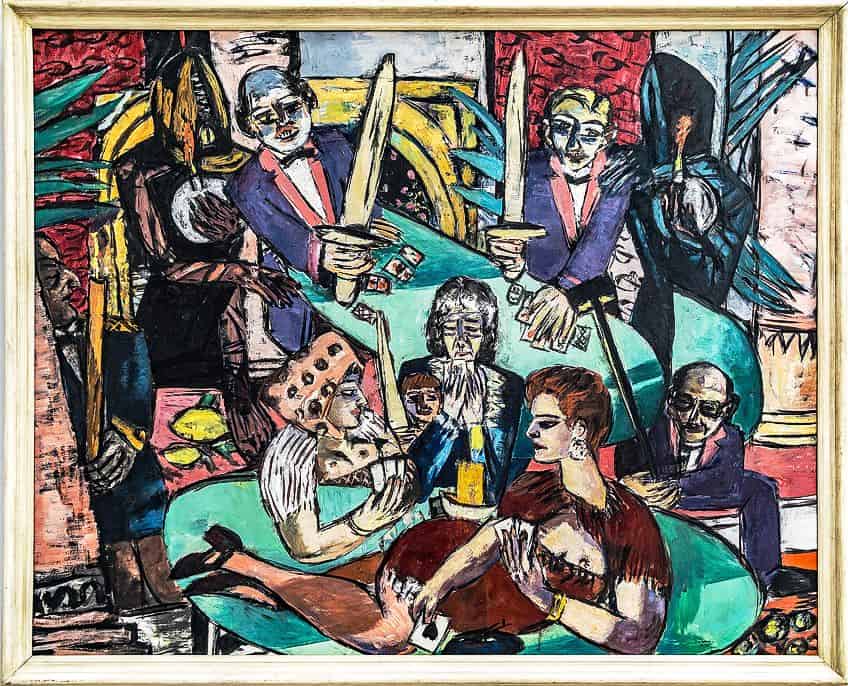

Departure (1935)

| Date Completed | 1935 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 215 cm x 314 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Beckmann started to paint this piece long before the Nazis came to power, and finished it shortly after they removed him from his Frankfurt teaching position. Despite claiming to be nonpolitical in lectures, Max Beckmann’s drawings display his rising uneasiness in the face of the savagery produced by the emergence of the Nazis. During the 1920s, he developed a taste for large-scale painting, which culminated in this, his first triptych.

Beckmann used the divided canvas’s extended format to highlight key episodes within a bigger narrative and to heighten the impact of his persistent story.

Even though the tripartite format was created centuries ago for Christian religious artwork, Beckmann believed it to be the right pattern for his modern kind of personal and societal allegorical picture. The triptych’s dimly illuminated right panel depicts a lady shackled to an upside-down guy, looking for a way out of her predicament but being prevented by a drummer in front of her and a scary bellhop behind her.

Beckmann depicted numerous persons in a torture cell, their wrists chained, required to comply with horrible acts of brutality, in the left panel.

Recommended Reading

We have just scratched the surface of Max Beckmann’s biography and art. There is plenty more to discover about Max Beckmann’s paintings and story. Here are some great book recommendations to aid you in learning more about this amazing artist.

Max Beckmann and the Self (2003) by Wendy Beckett

Max Beckmann, a German artist who lived through two world wars and produced almost a thousand pieces, was as innovative as he was prolific. Beckmann’s own words serve as an opening to the artist’s artistic expression and unrelenting pursuit of the self in this wonderfully crafted collection. Beckmann sought to identify himself via his artworks throughout his life.

- Beautifully produced volume uses his own words as an introduction

- Explores his creative expression and unwavering search for the self

- Careful analyses of more than 50 works

Max Beckmann (2003) by Susan Bieber

Max Beckmann was one of the best painters of the twentieth century, yet there hasn’t been an exhibition of his works in the art centers in over 30 years. Max Beckmann’s paintings were always figurative, yet muscular and mysterious, and has huge and frightening force, thus the dip in attention might be due to the significance of abstraction in 20th-century art. In the years leading up to World War I, Beckmann worked as a Naturalist and Symbolist.

- Sheds light on Beckmann's influence on the artists of his day

- Discusses his relationship with cultural politics in the 1920s and 1930s

- First comprehensive exhibition of his work to be seen since 1984

Max Beckmann established a distinctive pictorial technique after the war that combined expressionist hue and movement, mythical and mystical allusion, and the stark new realism of his depiction of daily life during the Nazi campaign of terror. Max Beckmann produced cryptic pictures and rich tableaux of unprecedented depth and intricacy throughout a journey that brought him from his native homeland in Germany to worldwide ports. He was a prodigious artist in painting, printmaking, and sketching, as well as a great sculptor.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Max Beckmann?

Max Beckmann established his visual style, employing a realistic idiom rich in symbolic connections to provide a dramatic portrayal of the twentieth century’s upheavals and their consequences. Travel had a crucial role in the life of the German painter. Nevertheless, the Nazi regime’s condemnation of him as a so-called degenerate artist led him to flee.

What Art Style Is Max Beckmann Known For?

Throughout his lengthy career, Max Beckmann’s talent of delicately layering people and symbols, as well as color and shadow, enabled him to masterfully turn his experience into engaging dramatic paintings. During World War I, the future artist worked as a medical officer, which spurred a fundamental shift in his artistic approach from a traditional, academic approach to a more socially aware and empathetic painting style. Throughout his career, he masterfully combined allegorical figures and real-life events in semiotically charged artworks that represented his perspective on the cultural, social, and political context.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Max Beckmann – Taking a Look at Max Beckmann’s Artworks and Legacy.” Art in Context. June 23, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/max-beckmann/

Meyer, I. (2022, 23 June). Max Beckmann – Taking a Look at Max Beckmann’s Artworks and Legacy. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/max-beckmann/

Meyer, Isabella. “Max Beckmann – Taking a Look at Max Beckmann’s Artworks and Legacy.” Art in Context, June 23, 2022. https://artincontext.org/max-beckmann/.