Tonalism – Exploring American Tonalism and the Paintings of the Style

In the 1880s, a new artistic style emerged when American artists began painting their landscapes with subtle tones of colored atmosphere. A decade later, American art critics started using the term “tonalism” to encapsulate this movement.

The Obscure Impressions of Tonalism

Examples of a Tonalism artist include Agnes Richmond, Bolton Brown, Emil Carson, and John Constable, but the two leading figures of this movement were George Inness and James McNeill Whistler. The aesthetic created by this diverse group of artists was radical for its time.

Tonalism would inform movements towards Impressionism and Abstraction and is still seen as prevalent today.

What Is Tonalism?

The Tonalism definition is misty, which is interesting because that is the official tonalism definition. When answering the question of what is tonalism, we refer to an American landscape art movement that featured subtle tonal ranges to convey mood or feeling.

Spanning from the 1880s to the 1950s, Tonalist landscapes became prevalent after the American civil war. Tonalism paintings depict a time of day when the tonal values appear closer, influencing the mood of the images.

The soft and blurry results suggest information instead of expressing it explicitly. The subtle paint handling and loose-edged, Romantic atmosphere of Tonalism paintings imbue a sense of spiritual solace that draws the viewer in and invite quiet contemplation.

The Tonalist Look

Tonalist landscapes are defined by a subdued color palette with neutral colors like gray, brown, or blue dominating these landscape scenes. The effect of the closely arranged values, often anchored by strong light or dark tones, is often referred to as chromatic harmony.

Instead of using sharp lines and color to indicate form, Tonalism artists use value units.

A tonalism artist uses broken touches like the Impressionists; there is no exaggerated impasto. Their gesture is based on the “put down a stroke and leave it” model but their stylistic touches are loyal to form. They still have edges and defined form but these are blended to achieve soft, dreamy atmospheres.

Tonalist landscapes depict broad expanses of land, water, or clouds. Often the sun or moon show up as beacons to other worlds or the humble haystack, which symbolizes the completion of labor. Tonalism portrays moments that enhance the landscape’s feeling of expanse. These paintings are not yet Impressionist works, so they are not focused on bright sunlight.

Instead, they emphasize different times of day and different times of the year, conveyed through cloud cover, reflections on water or snow, sunrises, or sunsets. They show the late afternoon, early evening, or dawn when the world is still at bay. There are hardly any figures in Tonalism paintings and when they do appear, they seem silent and solitary.

The Foundations of Tonalism

In the 1890s, the world had just discovered radiation, Darwin had just published his groundbreaking Origin of Species, the American civil war had just ended, and the world was facing the unstoppable force of industrialization, urbanization, and financial crises.

Tonalism purported to be something of a comfort for American viewers who needed art that slowed the pace of time, and evoked mystery and magic without becoming overly sentimental.

Tonalism was an important moment in art history which is illustrated by its relation to other important styles including the Barbizon School, Hudson River School, Luminism, and eventually Impressionism. Together, these landscape art movements established the traditions of painting outdoors, or en Plein air, which Impressionism has been credited for. The preceding movements also aimed for atmospheric impressions of the landscape.

Like the Impressionists, Tonalist artists made realistic images based on direct observation, but they were responding to the precise and patriotic renderings of the preceding Hudson River School.

Sharp, colorful compositions were replaced by subtle color effects and soft edges. The epic American landscapes of the Hudson River School were subsumed by more intimate views. Luminism, which followed the Hudson River School, was characterized by a crystal-like light and replaced by the moody atmosphere of the Tonalist artists.

French Barbizon

Traditional painters such as Nicholas Poussin often depicted scenes from antiquity in artificial arrangements that posed an ideal beauty. Poussin’s biblical scene Summer (Ruth and Baaz) (1660-1664) has a sense of order but, although it is painted in a naturalistic style and may have been based on a real landscape, it is unreal. Poussin did work en Plein air, but he saw these as preparatory studies on which he would later impose imagined scenes and would never dream of presenting his sketches as finished works.

In 1824, the Salon de Paris presented John Constable’s famous painting “The Hay Wain” (1821), which had an enormous impact on a particular group of French artists of the time. They were initially called “The School of 1830” because that is when they emerged. As the revolutions of 1848 raged on, they gathered at the village of Barbizon near the forest of Fountainbleau to manifest Constable’s ideas. They then became known as the Barbizon School which spanned from 1830 through to 1870.

Constable had been influenced by 17th-century Dutch painters who engaged strong shifts between lightness and darkness. In addition, the Anglo-Dutch tradition was an alternative to the Franco-Italian tradition because it depicted local landscapes. These images were not set in ancient Greece or the Bible but were vernacular. Thus, the French landscape became the central subject for Barbizon painters. They abandoned formalism and drew directly from nature which was then elevated from being a mere backdrop to ancient dramas.

Barbizon painters worked everywhere, but Barbizon was their spiritual headquarters. They saw its quaint forests as unspoiled spaces in which to live and paint. They were early conservationists in that they became attached to the woods and concerned about deforestation. Barbizon painters also placed an epic emphasis on the sky which Constable said was the “chief organ of sentiment”.

Leading figures of the Barbizon School included Théodore Rousseau, François Millet, Charles Francois Dorby, Jules Dupre, Virgilio Diaz, Paul Emanuel, Francois Louis, Narcisse-Virgile Diaz de la Pena, Constant Troyon, Charles-Emile Jacque, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, and Charles Francois-Daubigny.

In the late 1860s, the Barbizon School attracted a younger generation of French painters who visited Fountainbleau from Paris and painted the national landscape. These artists included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and Alfred Cicely, who would go on to be leading figures of Impressionism in the 1870s.

Théodore Rousseau was the godfather of Barbizon. He sketched outdoors a generation before the Impressionists, though he still completed his paintings in the studio. Between 1836 and 1848, each painting Rousseau submitted to the Paris Salon was rejected. Nonetheless, by the end of the 19th century, Rousseau’s works were widely admired and collected by wealthy Americans, in particular.

This influence would coalesce with American landscape painting movements like the Hudson River School to form Tonalism.

The Hudson River School Movement

The school of painting of the late 1800s to early 1900s, known as the Hudson River School, was the first native painting movement of the United States. It was known for its patriotism and celebration of the beauty of America’s natural resources.

The artistic nationalism of the Hudson River School appealed to Americans who felt nostalgic for the purity of the landscape which was being ravaged by the Industrial Revolution. Like the Barbizon artists, Hudson River School painters painted various places other than the Hudson River Valley.

Thomas Cole started as a portrait painter but was inspired by artists such as Thomas Dody to paint American landscapes. To this end, Cole moved to New York in 1825 searching for a landscape painting career. He gained instant notoriety with his paintings at the Catskills and became the leader of the Hudson River School movement. His followers included Albert Bierstadt, Jasper Cropsey, Asher B Durand, and Frederick Edwin Church.

Led by Cole, these artists focused on the notion of the sublime and instilled in the viewer sensations of awe similar to those that occur in the presence of nature. Their images explored a location through either the time of year or time of day and they incorporated hidden messages in the paintings which gave their work a mysterious and haunting air.

Frederich Church’s Mount Ktaadn (1853) featured a vast body of water in the middle ground and a farm boy leaning against the tree on the far-right side of the painting. The farm boy seems stuck between human intervention and the untouched world, gazing out into the expanse and the reflective surface of the water, making this a meditative image.

This device would become a key feature of Tonalism paintings, which were regarded as a link between the Hudson River School and Modern art.

Luminism

Active from 1850 to 1870, Luminism is a style of Romantic landscape painting which is regarded as an offshoot of The Hudson River School. It is often conflated with Tonalism and, while it is difficult to tell them apart, there are some significant discrepancies, the first being that Luminism emerged before Tonalism.

Luminism is closely tied to Transcendentalism, which was an American philosophical movement focusing on the inherent goodness of human beings and nature. The almost religious spiritualization of the American landscape is what sets Luminism apart.

In their search for truth, Luminists preferred reduced scenes. Unlike the theatrically sensational scenes of The Hudson River School, their paintings were extremely still, calm, and prioritized spiritual meditation over drama.

Like Tonalism, the name of the movement is indicative of its aesthetic. Luminist paintings feature glowing light which often reflects off bodies of water to create a Romantic or poetic atmosphere. Often using an aerial perspective, Luminist landscapes propose luminosity as a universal approach to spirituality.

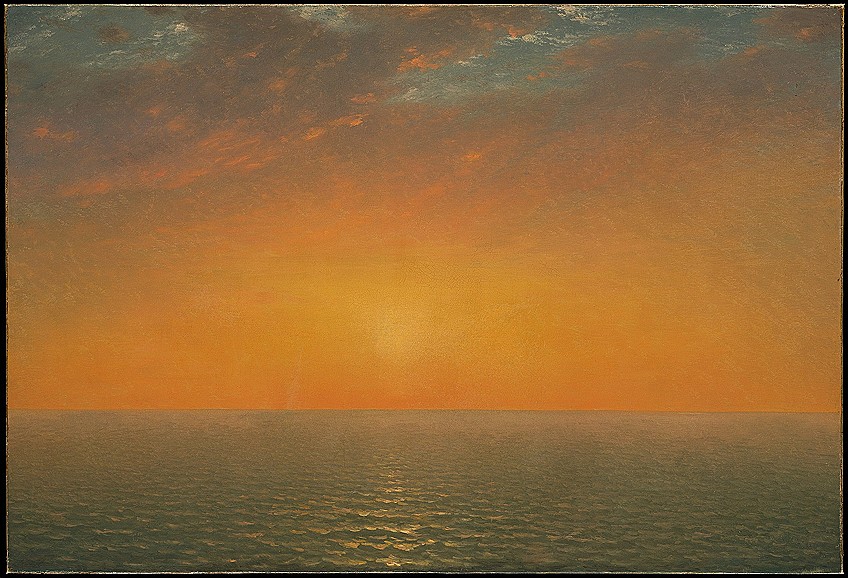

John Frederick Kensett was one of the masters of Luminism and his painting, “Sunset on the Sea” (1872), shows how often Luminists referred to light even in the titles of their works.

This painting depicts the sea and the sun with subtle shifts of light in the foreground. The godly sunset glow shines through clouds reflecting off the waves. This oil on canvas is housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

American Impressionism

What began to happen next would have a decisive impact on the shape of the art canon. American painters were gaining confidence in their traditions and presenting their work at international exhibitions. The World’s Fair of 1867 made it clear that American identity was tied to its landscapes.

The awe-inspiring paintings of these grandiose scapes seemed to be unique to the United States. European audiences and painters were beginning to recognize the American school of landscape painting.

Winslow Homer’s minuscule painting Artists Sketching in the White Mountains (1868) made a massive impression. Depicting a group of painters painting outside with their equipment and easels constitutes irrefutable evidence that the French were not the inventors of en Plein air painting. In this way, Homer is an integral part of the journey towards American Impressionism.

American artists also traveled abroad and were exposed to artists like Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot, who was a leading figure of the Barbizon School, which had become extremely popular with American collectors. Corot was initially an academic painter and had found enough success to spend his summers making his loose landscape paintings, which eventually became even more popular than his academic paintings.

Corot’s popularity inspired the rise of an American Barbizon, which has come to be known as American Tonalism.

Key Tonalist Painters

Like the French Impressionists, Tonalist artists were among the very first to begin painting modern scenery, as seen in Henry Ward Ranger’s Connecticut Woods (1899) and George Inness’ Harvest Moon (1891). But unlike the Impressionists who sought to capture light, these artists were attempting to imbue the landscape with mood and feeling.

Many American Impressionist painters practiced American Tonalism as well, and William Langston Lathrop’s “The Delaware Valley” (ca. 1899) demonstrated his suspension between Tonalism, which was more concerned with mood and atmosphere, and Impressionism, which sought to capture the effect of momentary light.

Some other well-known painters of the Tonalism movement include Homer Dodge Martin, Agnes Richmond, and Bolton Brown, but by virtually unanimous accounts, the most important Tonalists were Georges Inness and James McNeill Whistler.

Georges Innes (1825 – 1894)

| Birth Date | 1 May 1825 |

| Death Date | 3 August 1894 |

| Places Lived | New York, United States |

| Associated Art Movements | Tonalism, Hudson River School |

Like many other Tonalist artists of the 1800s, George Inness hailed from The Hudson River School. He became incredibly influential on other artists of the Tonalist style particularly because his artistic process was so different from that of many other painters of his time.

Inness is often noted for his energetic intervention on a canvas. His brushstrokes are rapid yet accurate. He came at a painting with every tool at his disposal to achieve the effect he desired.

His technique involved scratching, scraping, digging, glazing, and scumbling. Whenever he was unsatisfied with the results, he would simply layer another painting right over his previous experiments which resulted in interesting textural surfaces.

Moving away from the grand spectacle of The Hudson River School, Inness began to favor more intimate scenes like in “Keene Valley, Adirondacks” (1885) and “In the Gloaming” (1893) which are remarkably simple paintings. The compositions are calm, yet they demonstrate a delectable amount of energy and texture.

Expressing his thoughts and justifying his actions were part of George Inness’ artistic practice. He once said, “a work of art does not appeal to the intellect, it does not appeal to the moral sense, its aim is not to instruct, not to edify, but to awaken an emotion.”

James McNeill Whistler (1834 – 1903)

| Birth Date | 11 July 1834 |

| Death Date | 17 July 1903 |

| Places Lived | Lowell, United States, London, United Kingdom |

| Associated Art Movements | Tonalism, Impressionism, Aestheticism |

Whistler remains the quintessential figure of Tonalism. Whistler left America for Europe when he was 21 and he seemed to reject the nationalism that many respected American artists had embraced. But even half a world away, Whistler seemed unable to escape the fundamental ways in which he had been influenced by the conventions that had evolved to portray American landscapes.

Whistler’s “Nocturnes” series, which he made in London between 1870 and the mid-1880s, is a transposition of the American wilderness.

He was both challenging the style of American landscape painting and transforming it to its urban double. Whistler’s shadowy atmospheric spaces of a gritty night-time city owed a lot to the artist’s repudiated origins.

His contemplative figures are almost always meditatively directed towards some body of water, mostly the Thames River. This scheme references not only American landscape painting traditions but also important American poetic conventions of the mid 19th century. Nocturnes Blue and Silver – Chelsea (1871) depicts a figure who stands, gazing over an expanse of water surrounded by the urbanscape. Whistler’s liquid touch softens and fades the tones of the surrounding sea, gentle colors glistening in the night.

By spiritualizing the painted figure, Whistler was attempting to offer us access to hidden worlds. In thin skins of oil, Whistler layered subtle tones of dark colors, giving his gloomy surfaces a cool, somber effect. The painting’s plea for our passive attention gives it a synesthetic quality.

Another title Whistler used for his “Nocturnes” was that of symphonies, reinforcing the idea that the paintings were created simply to be enjoyed for their beauty.

Tonalism Today

Tonalism showed us that nature can be observed through tonal values and this has become a ubiquitous part of artistic understanding. However, many Tonalist followers clung too closely to its tenets, reducing it to a somewhat gimmicky and redundant tradition. As a result, Tonalism was quickly eclipsed by Impressionism and European modernism.

By the 20th century, Tonalism paintings were considered old-fashioned and suffered a devastating form of erasure in early surveys of American art and even the most astute observers relegated it to a mere footnote.

But as Tonalism is associated with the exploration of the subtleties of color relationships, it cannot ever truly disappear. While it may seem invisible, it is always there. Nowadays, it is not solely a painting phenomenon, but we see Tonalism in all manner of other media, particularly photography which is founded on a subtle exploration of tonal value.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Tonalism the Same As Barbizon?

Yes and no. American Tonalism was a product of the Barbizon School, but Barbizon was also known as French Tonalism.

What Is Tonalism in the Australian Context?

The Australian Tonalism definition is based on a movement that emerged in Melbourne during the 1910s. It is also referred to as the Max Meldrum School, after its founding figure. The Meldrum School of Tonalism artists was interested in finding scientific methods to accurately ascertain analogous value units.

Where Was the Hudson River School?

The Hudson River School was located around the Hudson River Valley in New York state, within the United States of America.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Tonalism – Exploring American Tonalism and the Paintings of the Style.” Art in Context. March 24, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/tonalism/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 24 March). Tonalism – Exploring American Tonalism and the Paintings of the Style. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/tonalism/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Tonalism – Exploring American Tonalism and the Paintings of the Style.” Art in Context, March 24, 2022. https://artincontext.org/tonalism/.