William Kentridge – Learn About the South African Artist

As one of the most celebrated South African artists of the 21st century, William Kentridge is world-renowned for his hand-drawn animated films, prints, and sculptures. Born in Johannesburg in 1955, Kentridge started making art at the height of apartheid in South Africa. Besides being a leading anti-apartheid artist at the time, Kentridge continues to be a role model for contemporary artists worldwide.

A William Kentridge Biography

| Date of Birth | 28 April 1955 |

| Country of Birth | Johannesburg, South Africa |

| Art Movements | Postmodernism, Video art, and Contemporary art |

| Mediums Used | Printmaking, drawing, theater productions, and animated films |

Over the past half-century, William Kentridge’s career has grown from strength to strength. This William Kentridge biography provides a brief overview of his life and work. In this article, we consider the socio-political conditions that shaped his artistic practice and how his career developed over the years.

Early Life

Kentridge was born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1955 to a wealthy Jewish family. Both of his parents, Sir Sydney Kentridge and Felicia Geffen, worked as anti-apartheid lawyers and human rights activists. Having this political background and family lineage will prove vital to Kentridge’s artistic career. Kentridge’s father famously defended Nelson Mandela during the “Treason Trials” of 1956 – 1961. His father also represented Steve Biko’s family after Biko’s brutal death whilst in police custody in 1977.

Kentridge spent his childhood in a large Johannesburg house, where he still lives today. He was exposed to Modern art from a young age.

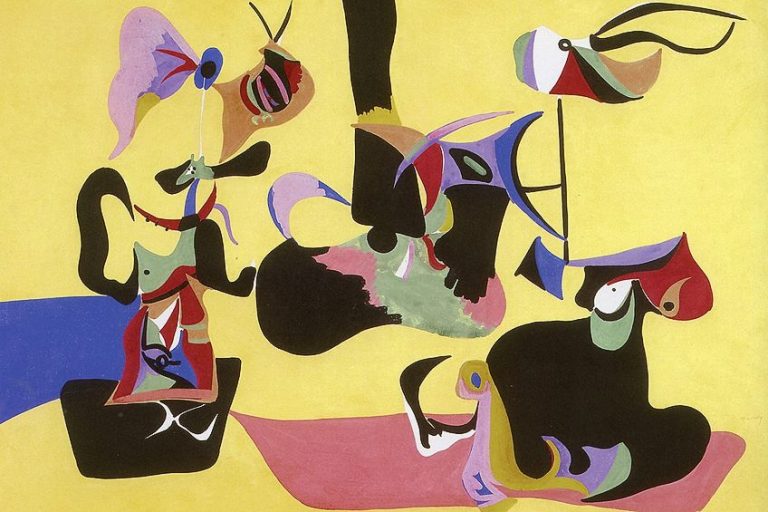

His childhood home was filled with reproductions of works by Matisse, Miro, Cezanne, and Modigliani. He was also frequently taken to the Johannesburg Art Gallery by his parents. Kentridge’s parents also had many friends who were artists, so the idea of becoming a successful artist was not uncommon to him.

Early Career

Upon graduating from the University of the Witwatersrand with a bachelor’s degree in politics and African studies, Kentridge enrolled at the Johannesburg Art Foundation, where he studied Fine Arts. His interest in African history and politics, however, remained with him and influenced his work. Due to his parents’ involvement in South African politics, Kentridge grew up acutely aware of the injustices in the country, and art became a form of expression for him.

Kentridge enjoyed his education but felt stifled by traditional painting styles. While his teachers promoted oil on canvas, Kentridge preferred charcoal drawing and etching.

In 1981, Kentridge changed courses again after being unsatisfied with his learning at the Johannesburg Art Foundation. This time, Kentridge left the country to study theater in Paris. A year later, Kentridge returned to South Africa. He felt like he would neither make a good painter, nor a good actor, but he nevertheless loved art and loved the movement and character of theater and film. For some time after his return, Kentridge worked as a stage prop assistant for a television series.

After struggling through years of what Kentridge calls his “early failures”, he turned to art again. This period of exploration was critical to his career development. Today, Kentridge advocates that failure is essential to the creative process. During this time of failure, exploration, and discovery, Kentridge found his own unique blend of expression that merges drawing, film, and performance.

This hybrid style of working became the signature characteristic of his mature work.

Mature Career

Apartheid reached its peak in South Africa during the 1980s. Apartheid laws denied basic rights to the majority black population and separated them from white society. While the system was dismantled in the early 1990s, the 1980s saw mass protests and social unrest. Given Kentridge’s political background and social awareness, he used his art to express his dissatisfaction with the apartheid regime.

What started as black and white charcoal drawings depicting scenes inspired by the South African political climate, soon developed into his own animation style that brought his drawings to life.

While traditional animation was created by sequences of drawings on separate sheets of paper, William Kentridge created his animations using only one sheet of paper. With quick actions, he would draw and erase movement on the paper as they evolved, taking photographic sequences as he worked. These images were then stitched back together, and the animation unfolded like a magical drawing in motion. Each updated image contained traces of the previous moment in softly blurred or erased charcoal lines.

This technique allowed for greater freedom and creativity in his work. He created complex and dynamic animations that were not possible using traditional animation methods. His layered animations were widely praised for their unique and inventive style. During the early 1980s, Kentridge married Anne Stanwix, an Australian-born doctor. They have three children together. In 1992, William Kentridge started working with the Handspring Puppet Company. Kentridge would continue to have many collaborative partnerships with filmmakers, musicians, and theater companies in the years that followed.

This allowed him to broaden the scope and ambition of his charcoal animated films. Over the next decade, Kentridge steadily became more prominent as an artist as he combined drawing, film, and theater to create unique works.

Several of his fictional characters appear recurrently in his animated films. These opposing characters include the capitalist Soho Eckstein in a business-like suit, and the dreamy artist Felix Teitelbaum. Both characters represent apartheid and conflicting forces that may exist within a single individual. According to Kentridge, both characters appeared to him in a dream. Kentridge’s films always show Felix Teitelbaum naked, and he is loosely depicted as a self-portrait of the artist. Kentridge admitted that this was mostly because he was too embarrassed to ask someone else to model for him.

Late Career

William Kentridge’s art first received international recognition when he exhibited at Documenta X in Kassel in 1997. Here, he showed two films featuring Soho and Felix. Soon after, Kentridge signed with the Marian Goodman Gallery. Goodman explains that Kentridge’s work at this time was in high demand. Goodman says, “We had so many institutions dying to show his work, and he had this full flowering”.

By the 2000s, Kentridge’s projects grew larger and more elaborate, embracing more collaborations. He branched out into opera in 2005, creating a contemporary interpretation of Mozart’s “The Magic Flute”, which was performed at Brussels’ La Monnaie.

In 2010, Kentridge collaborated with New York City’s Metropolitan Opera to produce Dmitri Shostakovich’s satirical theater production, The Nose, inspired by Nikolai Gogol’s surreal tale about a bureaucrat looking for his missing nose.In these years, Kentridge became South Africa’s most prominent contemporary artist. Among his major exhibitions were those at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Jeu de Paume in Paris, and the National Museum of Modern Art in Tokyo.

Kentridge founded the Center for the Less Good Idea in Johannesburg in 2016. The Center for the Less Good Idea is a platform for cross-disciplinary collaborations between creatives from all fields. It has become a hub for experimentation. The center encourages emerging South African artists and creatives to take risks, pursue their passions, and venture into new creative collaborations.

Kentridge’s newest theater production, “The Head & the Load”, was commissioned in 2018 by 14-18 NOW, a UK-based program. The production, which premièred in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, is a multimedia theatrical spectacle honoring African porters and carriers during World War I.

The impressive and critically acclaimed performance combines film projections, mechanized sculptures, dance, music, spoken word, and shadow play. Three years later, following the COVID pandemic, The Head & the Load has finally made its way back to Johannesburg as a touring show. Kentridge continues to live in his family home with his wife.

Important William Kentridge Artworks

William Kentridge’s artworks often use drawing, animation, and shadow puppetry to depict South Africa’s history, culture, and politics. He is internationally renowned for his large-scale projections, which often combine animation and live theater performance. Kentridge’s work has been exhibited in numerous galleries and museums around the world. Listed below are some of William Kentridge’s most important works that celebrate his immersive, spectacular style.

| Artwork Title | Date | Medium | Location |

| Koevoet (Dreams of Europe) | 1984 – 1985 | Charcoal on paper; triptych; each panel 100 x 73 cm | Robert Loder Collection |

| Johannesburg, 2nd Greatest City after Paris | 1989 | Animated film using charcoal and pastel drawings; 16mm film transferred to video; 8 min 2 secs | © William Kentridge |

| Arc/Procession: Develop, Catch Up, Even Surpass

| 1990 | Charcoal and pastel on paper | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

| Felix in Exile | 1994 | Animated film using charcoal, pastel and poster paint; 35mm film transferred to video; 8min 43sec | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

| Falls Looking Upstream (Colonial Landscapes) | 1995 | Charcoal and pastel on paper; 120 x 160 cm | Southern: a Contemporary Collection, South Africa. |

| Sleeper – Red

| 1997 | Etching, aquatint, and drypoint on paper | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

| Ubu Tells the Truth | 1997 | Animated 35mm film with charcoal drawings, drawings in chalk on a black background and documentary photographs and 16mm film transferred to video; 8 min | © William Kentridge |

| Black Box / Chambre Noir | 2005 | Installation; mechanized model theater, drawings, kinetic sculptures, and animated film projections | Commissioned by and exhibited at the Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin.

|

| I am not me, the horse is not mine

| 2008 | Video installation; 8 projections with color and sound | Collection of the Tate, United Kingdom |

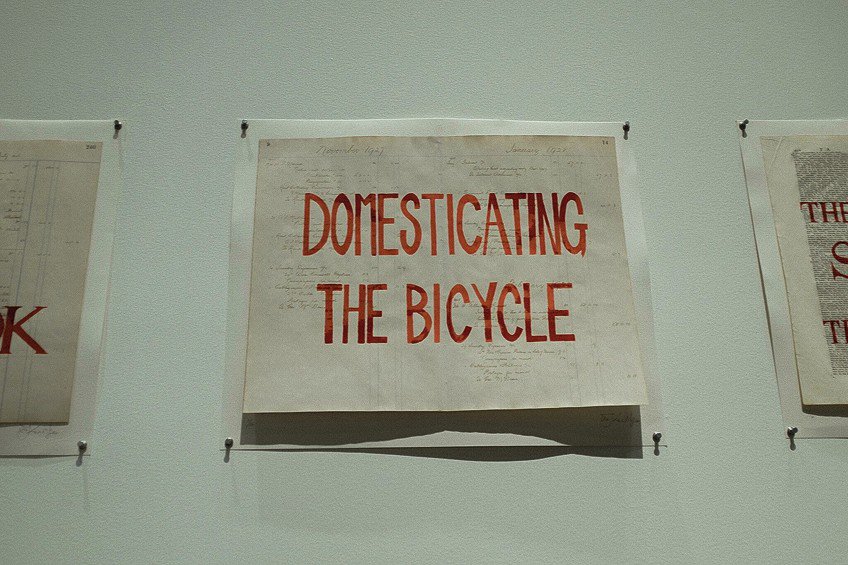

| Second Hand Reading

| 2013 | Flipbook film from drawings on single pages of the shorter Oxford English Dictionary; HD video with color and sound | © William Kentridge |

| The Shrapnel in the Woods

| 2013 | Indian Ink on Crabb’s Universal Technological Dictionary 1826 | Marian Goodman Gallery, New York |

| Notes Towards a Model Opera | 2015 | Three channel HD film installation; 11 minutes 14 seconds | William Kentridge Studio, Johannesburg © William Kentridge |

| More Sweetly Play the Dance

| 2015 | Eight channel video installation with four megaphones; sound | Marian Goodman Gallery, New York |

| The Head and the Load

| 2018 | Theater production | Premiered at the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall |

| Sibyl | 2019 | HD film; 9 minutes 59 seconds | William Kentridge Studio © William Kentridge |

| Hypsométrique de l’Empire Russe

| 2022 | Hand-woven mohair tapestry; 400 x 600 cm | William Kentridge Studio © William Kentridge |

Reading Recommendations

William Kentridge’s artworks have been widely exhibited in galleries and museums around the world, and his art has been featured in various publications. His art has also been the subject of documentaries and feature films. Here are our top three recommendations on books that provide an in-depth look at his life and work.

William Kentridge: Five Themes (2009), edited by Mark Rosenthal

Throughout his career, William Kentridge’s artworks explored five primary themes, which this impressive catalog explores in depth. The five themes include “Soho and Felix”, “Ubu and the Procession”, “Artist in the Studio”, “The Magic Flute”, and “The Nose”. The book also includes a DVD that Kentridge created especially for this catalog. The DVD includes fragments from his films along with commentary that explains his work in more depth.

- Investigates the five primary themes of Kentridge's career

- Includes fragments from significant film projects by Kentridge

- Book comes with a DVD made especially for this publication

Six Drawing Lessons (The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures) (2014) by William Kentridge

This fabulous book is one of the most comprehensive expositions of Kentridge’s views on art, artmaking, and the artist’s studio. Kentridge explains art as being its own kind of knowledge that cannot be fully understood in rational terms or academic reasoning. In this book, Kentridge unpacks the importance of the artist’s studio as a location for the creation of meaning and argues that art has the power to educate us about the most crucial problems of our time.

- Most comprehensive collection available on Kentridge’s art

- Includes Kentridge's thoughts on art, art-making, and the studio

- Ideal for those wanting to gain insight into William Kentridge

William Kentridge: In Praise of Shadows (2022), edited by Ed Schad

This expansive book explores Kentridge’s dynamic and highly original art practice. The book is organized chronologically and thematically, starting with Kentridge’s first charcoal drawings. It stretches into intersections with film, sculpture, theater, opera, printmaking, and a variety of other media. The publication includes an essay by curator Ed Schad, photographs of Kentridge’s studio, archival material, a conversation between Kentridge and Walter Murch, and a never-before-published lecture by Kentridge.

- Includes essays by Ann McCoy, Zakes Mda, and Ed Schad

- Presents and expands on Kentridge’s dynamic art practice

- Features a talk between Kentridge and the famous Walter Murch

Throughout his long and stable career, William Kentridge’s work continues to transform and evolve. He has created art in many forms, from drawings to sculptures, and even films. His works combine elements of theater, literature, music, and philosophy to create powerful messages that challenge viewers to think critically. Kentridge’s work is internationally renowned for stimulating thought and emotion. His work offers an unprecedented perspective on South Africans’ daily lives, both during and after apartheid.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Materials Does William Kentridge Use?

William Kentridge uses a variety of materials in his work, including charcoal, pastels, printmaking, and sculpture. He often ventures into cross-disciplinary work combining traditional art mediums with theater, music, and dance. This multi-disciplinary approach allows for dynamic and layered works that explore themes of collective memory, identity, social inequality, and personal reflection.

Why Does Kentridge Use Charcoal?

One reason that Kentridge started to use charcoal was because it is an inexpensive material. That is, however, not the only reason he is drawn to charcoal. Kentridge explains that he enjoys charcoal because of its malleability.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “William Kentridge – Learn About the South African Artist.” Art in Context. July 12, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/william-kentridge/

Attewell, C. (2023, 12 July). William Kentridge – Learn About the South African Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/william-kentridge/

Attewell, Chrisél. “William Kentridge – Learn About the South African Artist.” Art in Context, July 12, 2023. https://artincontext.org/william-kentridge/.