Paul Cézanne – Biography of the Famous Post-Impressionist

French painter Paul Cézanne was the greatest artist of the post-Impressionist period, and he was greatly admired near the end of his life for urging that Paul Cezanne’s art style remain in contact with its tangible, almost sculptural beginnings. Paul Cézanne’s paintings are acknowledged as laying the groundwork for the aesthetic and intellectual rise of 20th-century modernity. In hindsight, Cézanne’s arts are the most effective and necessary connection between the transitory features of the Impressionists and the more materialist creative trends of Cubism, Fauvism, Expressionism, and total abstraction.

The Life and Art of Paul Cézanne

Dissatisfied with the Impressionist axiom that artwork is largely a reflection of visual processing, Paul Cézanne attempted to transform his creative technique into a new type of logical technique. The painting itself becomes a monitor in his hands, registering the artist’s sensory impressions as he stares attentively, and frequently repeated, at a certain topic. Where was the artist from though, and how did Paul Cézanne’s paintings featuring big bathers known as Large Bathers (1905) become so widely renowned? Let us start with his early life.

| Date of Birth | 19 January 1839 |

| Date of Death | 22 October 1906 |

| Country of Birth | France |

| Associated Movements | Post-Impressionism, Cubism |

Early Life of Paul Cézanne

In 1839, Paul Cézanne was born in the southern French town of Aix-en-Provence. His father was a rich barrister and financier who pushed Paul to follow in his shoes. Cézanne’s last repudiation of his dominating father’s desires finally resulted in a drawn-out, troubling connection between the two, despite him being monetarily reliant on his parents until his father passed away in 1886.

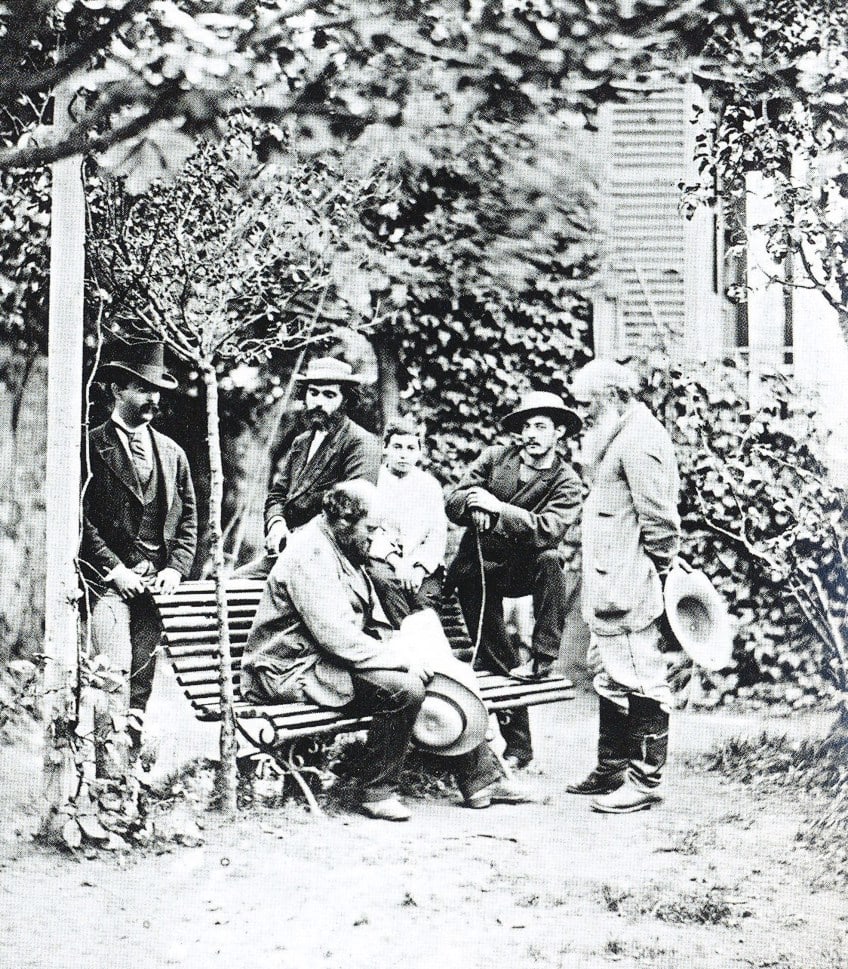

He was particularly good friends with Émile Zola, another Aix-born author who went on to become one of the best writer personalities of his period. The daring Cézanne and Zola were members of a tiny group known as “The Inseparables.” In 1861, the two artists relocated to Paris.

The Education and Career of Paul Cézanne

Cézanne was primarily self-taught as a painter. In 1859, he took part in evening sketching school in his hometown of Aix. Cézanne sought to attend the École des Beaux-Arts on two occasions after relocating to Paris but was dismissed by the judges on both occasions.

Early Training

Rather than pursuing professional instruction, Cézanne frequented the Musée du Louvre, where he copied masterpieces by Rubens, Titian, and Michelangelo. He also paid frequent visits to the Académie Suisse, a workshop where aspiring artists may sketch from a life drawing class for a low monthly subscription fee.

While still in the Académie, Cézanne met other artists Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, and Auguste Renoir, all of whom were poor painters at the stage but who would all eventually become founders of the fledgling Impressionist style.

Cézanne’s earliest oils were done in a fairly dismal tone. The paint was frequently used in heavy layers of impasto, giving weight to already melancholy works. His early paintings showed a preference for color over the shapes and viewpoints valued by the French Academy as well as the annual Salon’s jury, to which he consistently presented his works. Unfortunately, all of his applications were rejected. The painter also returned to Aix on a frequent basis to get funds from his displeased father.

1870 represented a watershed moment in Cézanne’s arts, precipitated by two events: the artist’s relocation to L’Estaque to evade the military conscription, and his closer relationship with one of the most famous emerging Impressionists, Camille Pissarro. Cézanne was enamored by L’Estaque’s Mediterranean environment, with its profusion of sunlight and vibrant hues.

Simultaneously, Pissarro was helpful in convincing Cézanne to use a lighter palette and eschew the dense, heavy impasto method in favor of smaller, more lively brushstrokes. Cézanne created a sequence of landscapes at L’Estaque that were dominated by the architectural shapes of the country homes, the bright blues of the ocean, and the vibrant greens of the vegetation.

Cézanne traveled back to Paris in 1872, where Paul, his son, was born. In 1886, his mistress would eventually become Madame Cézanne, right after his father died. Cézanne created around 40 pictures of his partner, as well as numerous mysterious portraits of their son.

Cézanne participated in the Salon des Réfuses in 1873, a renowned display of painters who had been rejected by the official Salon (he was within a circle that included Claude Monet, Édouard Manet, and Camille Pissarro, and others). The avant-garde painters were lambasted by reviewers, which evidently upset Cézanne severely.

During the next decade, he usually painted outside of Paris, in Aix or L’Estaque, and he stopped participating in unofficial group exhibits.

Mature Period

Cézanne’s experiences with creating from nature, as well as his rigorous experimentation, led him to establish his own artistic techniques. Cézanne sought authentic and permanent visual aspects of the things that surrounded him, as opposed to the portrayal of the temporary moment, which had long been preferred by the Impressionists. According to Cézanne, the painter must first “read” the topic of the picture by grasping its core.

The core must next be “realized” on a panel in the second step using shapes, colors, and spatial relationships. Colors and shapes consequently became the major features of his paintings, such as The Orgy (1867–1870), entirely free of the Academy’s stringent constraints of viewpoint and painting techniques.

Cézanne’s main objective was never to represent actuality as it was. He had said that he was attempting to disclose “something besides reality.” Cézanne’s still lifes were numerous in the 1880s, entirely revolutionizing the form in the two-dimensional style.

The important shift in focus from the things themselves to the shapes and colors transmitted by their surface and curves was the dominant characteristic of Cézanne’s still lifes.

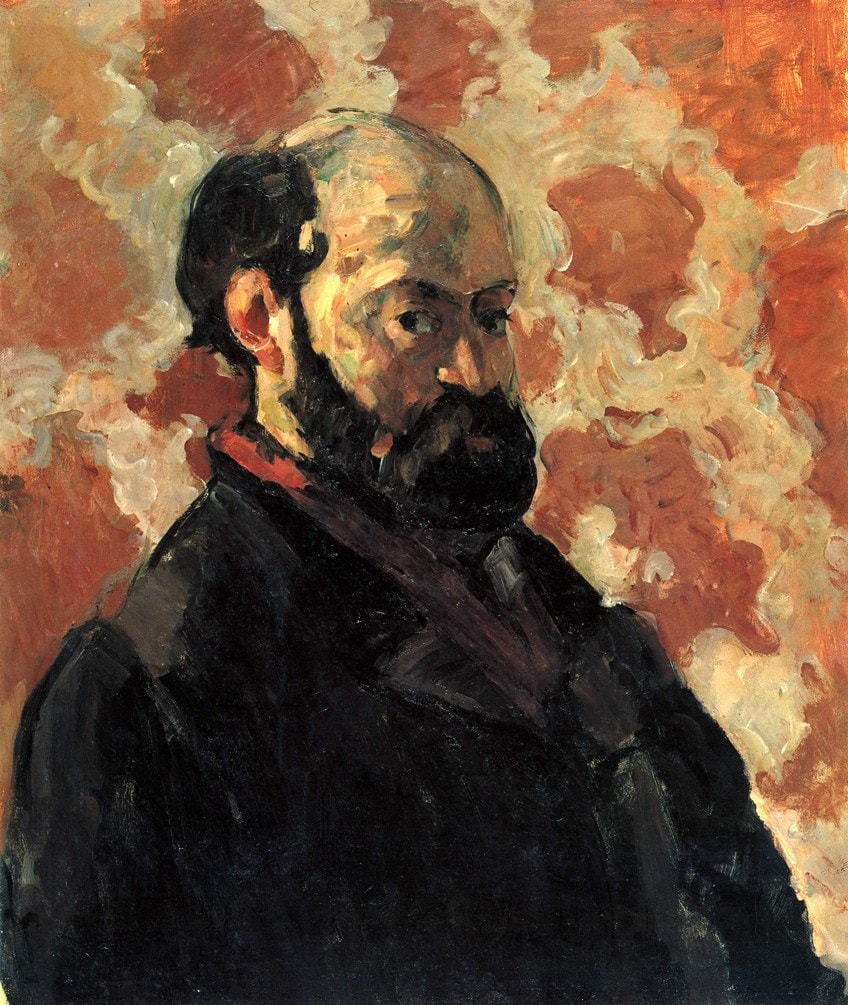

Cézanne’s portraiture, along with a large body of self-portraits, all reflect the same set of attributes. Examples of these include Portrait of Uncle Dominique (1886) and Achille Emperaire (1867–1868). The arrangements are intensely impersonal, as he sought to convey the structural and colorful potentials of the human form and its internal essence rather than the subject’s persona.

Late Period and Death

Cézanne’s creative endeavors were almost completely restricted to two graphic topics in the last ten years of his life. The representation of the Mont Sainte-Victoire, a majestic peak that commanded the arid and barren terrain surrounding Aix, was one example. The other was the culmination of the natural world and the human body in a succession of big bathers artworks.

The latter renditions of the big bathers were more abstract in terms of how shape and color seemed to merge on the surface.

Cézanne was out in the countryside when he was caught in a thunderstorm. He opted to return home after operating for two hours, but he fainted on the way. A passing car drove him home. His elderly housekeeper stroked his legs and arms to stimulate flow, and he regained consciousness as a consequence. He meant to resume working the next day, but he collapsed; the person with whom he was sitting phoned for aid; he was sent to his bed. He succumbed to pneumonia a few days later, on the 22nd of October 1906, and was laid to rest at his hometown of Aix-en-Saint-Pierre Provence’s Cemetery.

The Various Periods of Paul Cézanne’s Paintings

As with many artists, Cézanne’s arts underwent many changes in style through the years. Art scholars have been able to define several distinct periods in the artwork of Cézanne. Let us take a deeper look at these various periods.

1861 – 1870: The Dark Period

Napoleon III established the Salon des Refusés by order in 1863, where paintings refused for presentation at the Salon de l’Académie des Beaux-Arts would be shown. The young Impressionists, who were deemed subversive at the time, were among the painters whose paintings were denied. Cézanne was affected by their aesthetic, but his social interactions with them were abysmal—he appeared unpleasant, bashful, resentful, and depressed. His paintings during this time are distinguished by gloomy colors and significant usage of black.

They stand in stark contrast to his early watercolors and drawings at the École Spéciale de Dessin in Aix-en-Provence in 1859, and their brutality of emotion stands in stark contrast to his later works.

Cézanne made a sequence of works using a palette knife in 1867, influenced by the influence of Courbet. He subsequently referred to these pieces, which were large portraits, as une couillarde. Cézanne’s palette knife period was not merely the origin of contemporary expressionism, though it was inadvertently that; the notion of art as expressive orgasms made its first manifestation at this point.

Among the Couillard works are a sequence of images of Cézanne’s uncle Dominique, in which Cézanne created a style that “was as cohesive as Impressionism was fragmented. Later paintings from the dark period include sexual or brutal topics such as The Rape (1867), and The Murder (1868), which portrays a man slashing a lady who is being pinned down by his female collaborator.

1870 – 1878: Impressionist Period

After the Franco-Prussian War began in July of 1870, Paul Cézanne and his wife, Marie-Hortense Fiquet, fled Paris for L’Estaque, where he shifted his focus to landscapes. In January 1871, he was proclaimed to be a draft evader, but the war concluded the following month, in February, and the pair returned to Paris in the summertime of 1871. At the beginning of 1872, they relocated to Auvers. Cézanne’s mother was kept out of family gatherings, but his father was kept in the dark about Hortense for fear of inciting his fury. The artist got a monthly income of 100 francs from his father.

Pissaro and Cézanne produced landscapes together in Paris and Auvers.

Cézanne referred to himself as Pissarro’s disciple for a long time afterward. Cézanne began to forsake dark colors under Pissarro’s direction, and his paintings became considerably lighter. Cézanne went between Paris and Provence after abandoning Hortense in the region of Marseille, participating in the first and third Impressionist exhibitions in 1877. In 1875, he drew the notice of collector Victor Choquet, whose purchases helped him financially. However, Cézanne’s exhibited works elicited laughter, wrath, and ridicule.

“This odd-looking head, the color of an old boot, may give a pregnant woman a jolt and produce yellow fever in the fruits of her uterus before its advent into the universe,” observed reviewer Louis Leroy of Cézanne’s picture of Choquet.

Cézanne’s father learned about Hortense in March 1878 and vowed to cut him off monetarily, but in September he softened and agreed to send him 400 francs for his household. Cézanne moved back and forth between Provence and Paris until Louis-Auguste had a workshop constructed for him at his property in the early 1880s. This was on the top story, and an expanded window was installed, bringing in northern light but breaking up the line of the eaves; this feature still exists. Cézanne established himself in L’Estaque. In 1882, he worked with Renoir there, and in 1883, he visited Monet and Renoir. A popular artwork from this period is A Modern Olympia (1873-1874).

1878 – 1890: Mature Period

The Cézanne family settled in Provence at the start of the 1880s, where they lived for the rest of their lives, save for occasional trips abroad. The relocation indicates new freedom from the impressionists based in Paris, as well as a strong predilection for the south, Cézanne’s native land. Hortense’s brother owned a home at L’Estaque with a vista of Montagne Sainte-Victoire.

The “Constructive Period” refers to a series of paintings of this peak from 1880 until 1883 and also of Gardanne from around 1885 until 1888. The year 1886 marked a watershed moment in the family’s history. Hortense became Cézanne’s wife.

Cézanne’s father passed away in 1886, giving him the property he had acquired in 1859. By 1888, the family had moved into the old manor of Jas de Bouffan, a big home, and gardens with facilities that provided them with newfound luxury. This mansion, with significantly smaller grounds, is presently owned by the city and is available to the public on a limited basis. For several years, it was assumed that Cézanne severed his acquaintance with Émile Zola after he used him as the inspiration for the failed and ultimately fatal fictional artist Claude Lantier in the novel L’œuvre (1886) Recently, letters were unearthed that contradicted this. A letter from 1887 reveals that their relationship lasted for at least a little after that. An artwork called Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1890) was made around this time.

1890 – 1906: Final Period

Cézanne’s peaceful time at Jas de Bouffan was fleeting. From 1890 until his demise, he was plagued by disturbing circumstances, and he retreated deeper into his paintings, spending long periods as a complete loner. His works were well-known and highly sought for, and he earned the admiration of a new generation of artists.

The issues began in 1890 when he was diagnosed with diabetes, which destabilized his temperament to the point that his connections with others were once again compromised. He went to Switzerland with Hortense and his child, maybe expecting to mend their marriage. Cézanne, on the other hand, went to Provence to reside, while Hortense and Paul Junior moved to Paris.

Hortense returned to Provence, but in different living accommodations, due to financial constraints. Cézanne relocated to live with his sister and mother. He converted to Catholicism in 1891.

Cézanne, like previously, rotated between working in Jas de Bouffan and in the Paris area. He made his first visit to Bibémus Quarries and ascended Montagne Sainte-Victoire in 1895. He must have been impressed by the complex environment of the quarries since he rented a hut there in 1897 and painted substantially from it. The forms are thought to have influenced the early “Cubist” aesthetic. Also that year, his mother passed, which was sad but allowed him to reconcile with his wife. He sold his place at Jas de Bouffan and moved to Rue Boulegon, where he established a workshop.

Nevertheless, the relationship remained tumultuous. He needed a quiet area to himself.

In 1901, he purchased some property along the Chemin des Lauves, a secluded road on high terrain near Aix, and ordered the construction of a workshop there. In 1903 he relocated there. Meanwhile, in 1902, he created a will in which he excluded his wife from his inheritance and left it all to his son. The relationship appears to have deteriorated; she is believed to have burnt his mother’s memorabilia.

From 1903 till his death, he worked at his workshop, spending a few weeks in 1904 with Émile Bernard, who remained as a house guest. After he had passed, it was turned into a monument known as Les Lauves. The dramatic painting Pyramid of Skulls (c. 1901) was made in his final period.

Artistic Characteristics of Paul Cézanne’s Paintings

It is hard to overlook the formation of a distinct aesthetic style in Cézanne’s later work. With his artworks, the artist provided a new way of observing the world. As his renown grew in the last years of his life, a growing proportion of young artists were influenced by his unique vision.

Of them was a youthful Pablo Picasso, who would soon guide the Western heritage of art in a completely new and unforeseen path. Cézanne encouraged the new generation of painters to separate form from color in their work, resulting in a fresh and subjective graphic reality rather than mindlessly copying.

Cézanne’s impact lasted far into the 1930s and 1940s, when a new creative style, Abstract Expressionism, was emerging.

Cézanne applied colors to his canvases in a series of defined, careful brushstrokes, as if he were “trying to create” a picture rather than “painting” it. As a result, his work adheres to an intrinsic architectural aesthetic: every area of the canvas should contribute to the canvas’s greater structural structure. In Cézanne’s mature works, even a simple apple may have sculptural intricacy. It’s as if each Cézanne still life, landscape, or portrait has been seen from a variety of angles, its material elements reconstructed by the artist as more than simply a replica, but as what the artist referred to as “a harmonious counterpart to nature.”

This aspect of Cézanne’s systematic, time-based work led the Cubists to see him as their creative teacher.

Paul Cézanne’s Exhibitions

Paul Cézanne’s paintings were included in the inaugural Salon des Refusés exhibition in 1863, which featured works rejected by the judges of the annual Paris Salon. From 1864 until 1869, the Salon dismissed Cézanne’s offerings every year. Until 1882, he kept sending paintings to the Salon. Through the influence of fellow artist Antoine Guillemet that year, he displayed The Artist’s Father, Reading L’Événement (1866), his very first successful Salon entry, as well as his last one.

Later, a few isolated works were displayed at various places until 1895, when Ambroise Vollard, a Parisian dealer, offered the painter his first solo exhibition.

Despite rising public acclaim and profitability, Cézanne decided to labor in greater creative solitude, frequently working in his cherished Provence, distant from Paris. He specialized in a few categories and was equally skilled in each: still lifes, landscapes, and bather studies. Due to a shortage of suitable nude models, Cézanne was forced to construct from his mind for the final.

His portraits, like his landscapes, were inspired by what he knew, therefore subjects included not just his son and wife, but also local villagers, children, and his art collector, such as The Overture to Tannhauser: The Artist’s Mother and Sister (1868). Cézanne’s still lifes are ornate in style, created with heavy, flat surfaces, and have the weight of Gustave Courbet.

The “props” for his paintings may still be discovered at his workshop, in the outskirts of contemporary Aix, just as he left them. Cézanne’s arts were not welcomed by Aix’s tiny elite. In 1903, Henri Rochefort attended an auction of artworks once owned by Zola and wrote a very critical piece titled “Love for the Ugly” in L’Intransigeant on the 9th of March, 1903. Rochefort tells how attendees allegedly burst out laughing when they saw the works of “an ultra-impressionist called Cézanne.”

The people of Aix were incensed, and for many days, editions of L’Intransigeant landed on Cézanne’s doorstep, along with letters urging him to depart town because “he was disgracing.”

Paul Cézanne’s paintings were shown at a major museum-like retrospect exhibit in Paris in September of 1907, following his death in 1906. The Cézanne exhibition at the Salon d’Automne in 1907 had a significant impact on the direction of the avant-garde in Paris, confirming his status as one of the most prominent artists of the 19th century and ushering in Cubism.

The Legacy of Paul Cézanne’s Art Style

When shown among the Impressionists, Paul Cézanne’s paintings were repeatedly disregarded by the authoritative Salon in Paris and mocked by critics. Nonetheless, younger painters who visited Cézanne’s workshop in Aix regarded him as a master throughout his lifetime. Cézanne’s arts, like those of Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, impacted Matisse and many others antecedent to Expressionism and Fauvism, with their feeling of urgency and incompleteness.

Cézanne is regarded as one of the most influential artists of all time.

We learned from him that changing the color of a thing means changing its structure. His work demonstrates unequivocally that painting is not the art of replicating an object with colors and lines, but of giving firm, yet malleable, expression to our nature. Cézanne’s landscapes, such as The Neighborhood of Jas de Bouffan (1885–1887), inspired Ernest Hemingway to relate his writing to the artworks.

“I was understanding something from Cézanne’s art that made writing basic accurate phrases far from enough to give the narratives the depths that I was attempting to put in them,” he wrote. Cézanne’s experiments with geometric simplicity and optical phenomena encouraged Braque, Picasso, Metzinger, and others to explore increasingly more complicated perspectives of the same subject, finally leading to form fracture. Cézanne thus launched one of the most innovative fields of creative inquiry of the 20th century, one that would have far-reaching consequences for the creation of contemporary art.

Picasso called Cézanne “the parent of all of us” and declared him “my single master!” Cézanne’s talent was recognized by other artists such as Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Paul Gauguin, and many others.

Famous Paul Cézanne Paintings

Cézanne was a prolific and famous artist. He created many famous works such as his paintings of big bathers and Cézanne’s still life paintings. Here is a list of some of his works created throughout his lifetime:

- The Hanged Man’s House (1873)

- A Modern Olympia (1874)

- Self Portrait (1875)

- Bather (1887)

- Mardi Gras (1888)

- The Card Players (1893)

- Rideau, Cruchon et Compotier (1894)

- Madame Cézanne in a Red Dress (1894)

- Woman with a Coffee Pot (1895)

- The Large Bathers (1906)

Book Recommendations

Paul Cézanne is known for his famous French Post-Impressionist artworks. He experienced many ups and downs in his career, and it is almost impossible to fit all the interesting information into a single article. Therefore, we have created a list of book recommendations for your further reading pleasure.

Cézanne: A Study of His Development (Kindle) by Roger Fry

Roger Fry, the late art critic, had unrivaled intuition and impact. One of his aims was to fight for a deeper comprehension of the Impressionist school and, above everything else, to secure the magnificent place that was rightly Cézanne’s. Fry offers a critical critique in Cézanne that has never been exceeded in many ways.

He accomplished with notable success a dual goal: to demonstrate the fundamental growth of the artist’s talent and to examine his works as it truly is; or, as Fry puts it, “to discern the deep contrast between Cézanne’s statement and what we have constructed of it.” The outcome is a book, written in Fry’s most straightforward, perceptive style, that is of tremendous technical value to the artist and pupil, and that provides an enlightening exposition of the core character of Cézanne’s work to the layperson.

- Roger Fry was an art critic of unequaled perception and influence

- A critical analysis which in many aspects has never been surpassed

- An illuminating demonstration of the nature of Cézanne’s art

Cézanne in Provence (2006) by Philip Conisbee

This gorgeous book, released to commemorate the centennial of Paul Cézanne’s death, highlights the artist’s portrayals of his home Provence. While Cézanne is widely regarded as one of the modernists’ forefathers, this book concentrates on his personal sense of accomplishment, particularly as a painter investigating the environment in and around his birthplace of Aix-en-Provence. Despite spending time in other parts of France, particularly Paris, Cézanne returned to Provence on several occasions, where he spent practically the whole last 20 years of his life.

- Celebrates the artist’s depictions of his native Provence

- Focuses on Cézanne's own sense of achievement as a painter

- Beautifully illustrated with some 160 paintings and watercolors

The Letters of Paul Cézanne (2016) by

We are familiar with Cézanne the painter, the pioneer of aesthetic modernism that profoundly influenced the 20th century. We know less about the letter-writer, but this is no less significant. He never ceased sending letters from 1858 till his death in 1906. They are intimate, friendly, and intellectual, and they are necessary for comprehending the man, with his impetuosity, pains, and generosity. Those he addressed to his oldest friend, Emile Zola, are particularly poignant. We shall encounter an artist who reflects on his work: whether he addresses Pissarro (adoringly) or the Superintendent of Fine Arts (violently), it is always for the greater glory of painting. This is a must-have book that contains all of the painter’s correspondence.

- Cézanne's correspondence reveals both heroic and human qualities

- New translation includes over 20 unpublished letters

- Reproduces Cézannes original sketches and caricatures

The finest artist of the post-Impressionist period was French painter Paul Cézanne, and he was much respected near the end of his life for demanding that Paul Cezanne’s art style keep in contact with its palpable, almost sculptural roots. The paintings of Paul Cézanne are widely regarded as establishing the framework for the aesthetic and intellectual development of 20th-century modernism. In retrospect, Cézanne’s arts constitute the most efficient and essential link between the Impressionists’ ephemeral qualities and the more materialist creative approaches of Cubism, Fauvism, Expressionism, and absolute abstraction.

Read also our cezanne web story.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Paul Cézanne?

During the late 1870s, French artist Paul Cézanne developed his own style and avoided being involved with other Impressionist painters. He also found fulfillment in working alone in his homeland in Southern France. Some of the reasons for his desire to work alone included the fact that the personal orientation of his works did not correspond with the brilliance of other Impressionists. Furthermore, his works garnered unfavorable comments from a larger number of people. This was also the reason he didn’t want to reveal his art publicly for roughly 20 years following his impressionist exhibition.

What Was Paul Cézanne’s Art Style?

Cézanne used colors to the canvas in a series of defined, careful brushstrokes, as if he were “trying to create” a picture rather than “painting” it. As a result, his work adheres to an intrinsic architectural aesthetic: every area of the canvas should contribute to the canvas’s greater structural structure. In Cézanne’s mature works, even a simple apple may have sculptural intricacy. It’s as if each Cézanne still life, landscape, or portrait has been seen from a variety of angles, its material elements reconstructed by the artist as more than simply a replica, but as what the artist referred to as “a harmonious counterpart to nature.”

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Paul Cézanne – Biography of the Famous Post-Impressionist.” Art in Context. December 30, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/paul-cezanne/

Meyer, I. (2021, 30 December). Paul Cézanne – Biography of the Famous Post-Impressionist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/paul-cezanne/

Meyer, Isabella. “Paul Cézanne – Biography of the Famous Post-Impressionist.” Art in Context, December 30, 2021. https://artincontext.org/paul-cezanne/.