Political Art – How We Use Art As a Political Statement

Of all the swathes of artworks we encounter in our lives, some pieces have the ability to change our world. These artworks shape our views, reinforce them, or create new lenses through which we see the world. This is the domain of political art – where art and the human experience dance together.

Political Art

Often messy but always powerful, political art influences the way history unfolds, looking both backwards and forwards in time. Political art sits at the heart of social change, and closely describes and affects the ways we live. This article explores the significance of social issue art, its different types, and some of the most famous political art.

What Is Political Art?

Many say that all art is political. They are not wrong. Art and society have long been inseparable, creating new identities and shaping our understanding of the world. Art is also affected by political changes, events, and ideologies. For centuries, art and politics have been influencing each other. Regardless of how an artwork became political, however, it is important to understand that all art can be political based on the context in which it is produced, distributed, and observed. The question still begs though, what is political art? Or what is political in art? Political art is any art that brings awareness or comment to a social or political issue, in order for it to be interpreted and understood by the viewing public.

Because art is subjective, social issue art is often deeply entangled in the political views of the artists themselves.

Political art can either critique or support an existing status quo, point of view, or government. Over the years, political art has been used to challenge authoritarian rule, demand rights, or bring recognition to vulnerable groups. Just as much, political art has been used to enable bigotry and drive nations into war. Art as a political statement is thus complex, packed with both negative and positive possibilities. Most importantly, however, political art is about change. For better or worse, political artists are inspired by the will to change their societies in response to injustices or concerns they perceive. At the very least, art as a political statement seeks to bring awareness so that others can bring change.

Ancient Political Art

Political art has its roots in the Ancient period. One could argue that even the Rosetta Stone is a political artwork, since it carried an inscription of a political decree on its face. But Ancient social issue art rarely appeared how it does today, and rarely made the kind of impact that political artworks do in the present. Most Ancient political art focused on legitimizing the power of rulers to gain respect and loyalty from their subjects.

These political artworks usually included intimidating masks, elaborate headdresses, and fine jewelry.

In some Ancient societies, sculptures and inscribed portraits would preserve the legacy of political leaders. In smaller-scale Ancient societies, political art tended towards providing social or political education to subjects, often by relating to spiritual forces that people believed in. These artworks were used to instill fear or indicate the benevolence of spiritual entities. This type of political art dominated the Ancient period as artists had little freedom to express their personal political leanings. Between the 1200s and 1600s as well, political art mainly remained a tool for ruling elites to solidify power. But as the world changed over the centuries, so too did political art.

What Are the Types of Political Art?

Because the genre is multifaceted, there are numerous different types of political art. As much as there is political propaganda in art, there is also satiric, participatory, and activist political art, but all fall under the three main categories of Portrayal, Promotion, and Projection.

Portrayal

Sometimes the mere topic of an artwork is enough to make it political. By documenting a specific event, artists can make political claims by observing and representing the event through art. Political artwork that falls into the category of Portrayal usually depicts real-life occurrences that have happened in the past or are occurring presently.

People relate to these artworks according to their own positions and experiences in society.

Realism and naturalism are common themes in the political art of Portrayal. The perspective of the artist still matters here, but the main goal is to provide accurate and faithful depictions of reality. Different individuals take on different stances after viewing the artwork. A painting of the fall of the Berlin Wall, for example, realistically portrays a social event while creating different opinions among people who view it, fueled by their own experiences and memories.

Promotion

Political art as Promotion is less neutral and involves more of the artist’s own political views. Promotional political art is all about finding resolutions to social events and dramas. But to provide a resolution is also to involve one’s own opinion in the artwork, and so subjectivity is more deeply ingrained in this type of political art. This is often where we see political propaganda in art.

Certain elements of the scene are privileged over others, and the artist makes conscious choices about the message they want to deliver to the viewing audience. The artist evokes emotion from the viewer, strengthening their belief in the political message that the artwork presents. Promotional political artworks have a clear meaning and inspire those who agree with the message. This type of political art is often realist in style but enjoys creative space for narrative experimentation.

Projection

Projection is the most destabilizing of all types of political art, as it imagines worlds that are yet to come. It is the political art of what could be, involving the use of varied artistic elements. Artworks of this type rarely portray events or make direct political arguments, they instead become political solely because of how they challenge and break boundaries of the existing status quo in both art and politics.

Political messages are usually hidden in the artwork or require personal interpretation to acquire meaning.

For this reason, these artworks can be appropriated and picked up on by individuals of differing political views. The movements of Dada and Surrealism are examples of this type of political art, not for their direct political statements but for the way they shifted the status quo in society.

Famous Political Art

Below is a list of ten of the most famous political artworks and political artists. You will note how political art has evolved since the ancient period – artists infuse more creativity into their work, and their political messages are more nuanced, all the while changing the artform itself in the process.

The Death of Marat (1793) by Jacques Louis-David

| Artist | Jacques Louis-David (1748 – 1825) |

| Date of Artwork | 1793 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 162 x 128 |

| Housed | Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, Brussels, Belgium |

Jacques Louis-David remains one of the most influential French artists in history, not only for his own technical brilliance but for the ways he captured the French Revolution on canvas. Louis-David grew up in Paris before moving to Italy to perfect his artistic talent. While there, he was influenced by Rococo and Baroque art, which he eventually combined and superseded with Neoclassicism. Baroque is an art style notable for its grandeur and flamboyance, making use of rich colors and intensive detail to convey emotion and dramatism more so than direct political themes. Even though he eventually overcame these genres with Neoclassicism, Baroque elements of drama and vividity still hide in his paintings. Neoclassicism, a movement synonymous with Louis-David today, was known for having political or moral themes, a response to the political neutrality of Rococo.

Louis-David was a supporter and propagandist of the Jacobins, the group that drove the revolution and unseated the French monarchy. Rococo was the official art style of the monarchy at the time, and artist-revolutionaries like Louis-David saw it as overly dramatic, detached, and excessive. By forwarding Neoclassicism and rejecting Rococo the artist posed a political challenge to the government, using the new genre to express themes and styles that were rejected in the past. His repertoire of political art – before, during, and after the revolution – is massive, but one of his most famous political paintings remains The Death of Marat (1793).

The Death of Marat (1793) depicts a real-life scene in which the prominent Jacobin leader Jean-Paul Marat has been murdered in his bath.

At this point in the French Revolution, the democratic ideals that inspired it in the first place were quickly being forgotten as different political factions battled for power. Marat, belonging to the Montagnard faction, was murdered by Charlotte Corday who supported the opposing Girondins. She blamed Marat for his involvement in numerous executions that had taken place as part of the Reign of Terror. Even though Marat was indeed a central figure in these executions, Louis-David’s portrayal of the murder quickly added more fuel to the fire, and support for the Montagnards strengthened. This is the power of political art – to shape perception. People overlooked Marat’s previous injustices after witnessing this painting, as Louis-David successfully presented him as a tireless revolutionary who had been betrayed by conniving forces.

In the painting, Louis-David is promoting a particular point of view. But how does he do this, seeing that the painting is simply a portrayal of an event? This is the mark of a good political artist. He manipulated various elements in the scene to subtly suggest a certain political argument, using art as a political statement. Marat is painted as a traditional religious martyr covered in a holy glow, taking his last breaths, with pen in hand to indicate his commitment to the revolution.

It was unlike Louis-David to make use of such dramatic imagery, but he was aware that it would resonate across the nation, as only twenty years before this was the main artistic style.

It certainly resonated. The Reign of Terror only worsened after this painting’s release. Many innocent lives were lost as a result of the paranoia that followed Marat’s death and Louis-David’s venerous depiction of him. After the revolution, Louis-David shifted his allegiances to the new emperor Napoleon, for whom he produced political art as well. Paintings such as Napoleon Crossing the Alps (1802) and The Coronation of Napoleon (1807) are political in that they provided legitimacy and glory to Napoleon’s claim to the throne.

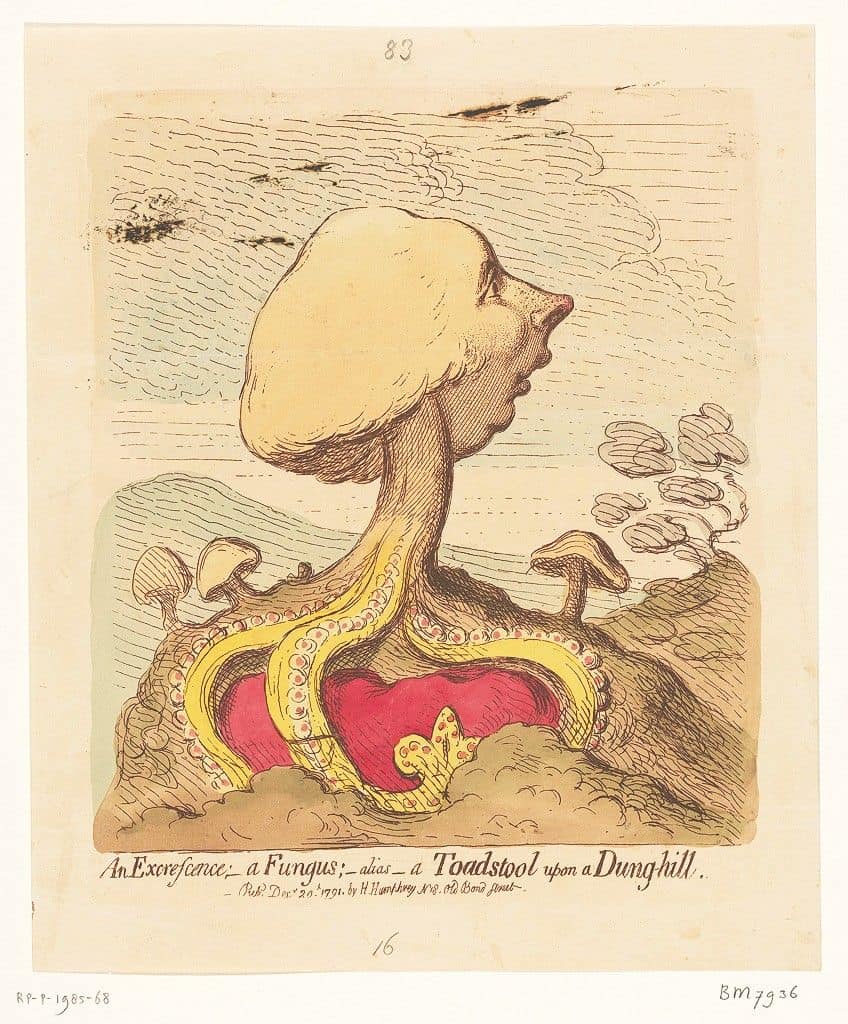

The Plumb-pudding in Danger (1805) by James Gillray

| Artist | James Gillray (1756 – 1815) |

| Date of Artwork | 1805 |

| Medium | Hand-colored etching |

| Dimensions (cm) | 26 x 36 |

| Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

Another popular type of political art is satire. Satire arrives in many different mediums, sometimes as comic strips and sometimes as paintings, and seeks to bring political awareness or make political arguments via comedic effects. Back at the turn of the 19th century in England, political satire was slowly becoming an influential way in which people were forming opinions about politics and society. James Gillray was a highly important artist in this regard. Sometimes referred to as “the father of the political cartoon” by art historians, Gillray’s specialty was bringing creative humor and wit into his famous political art. His formative artistic training was in etching and aquatinting, producing works at the Royal Academy that gradually brought attention to his skill.

Alongside William Hogarth (another esteemed English political cartoonist by whom Gillray was inspired), he is recognized as one of the most influential and prescient political artists of all time.

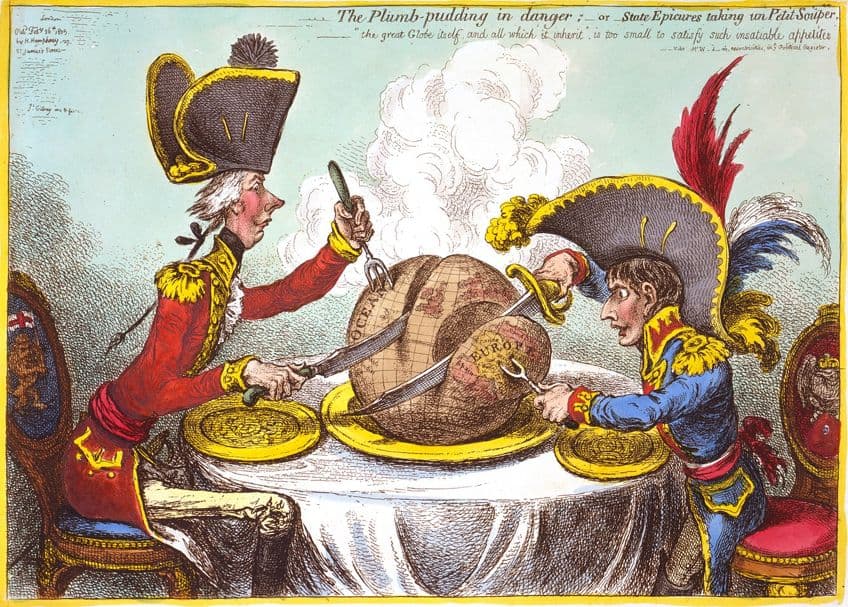

Gillray produced roughly 1600 cartoons, caricatures, and prints throughout his long and successful career as a political artist. The Plumb-pudding in Danger (1805) is, however, easily his most lasting work. The image he produced back then has been reinterpreted by political cartoonists ever since, making it one of the most well-known political cartoons in history. The caricature of the globe being brashly divided into parts by powerful rulers, like a meal on a table, has reappeared in times of conflict ever since. In Gillray’s original version, Emperor Napoleon and the English Prime Minister William Pitt divide a figurative plumb pudding of the globe with the British Isles at the center. Napoleon slices away at Europe, while Pitt cuts off a piece of the West Indies – an accurate depiction of both countries’ imperial ambitions at the time. By analyzing the cartoon, however, we see how Gillray made subtle political arguments.

Napoleon is portrayed in a frenzied state with Pitt at ease, and their differences in physical size are also played upon. Note the utensils of the rulers, and how Napoleon makes use of an army sword, which is meant to symbolize an aggressive militaristic approach. This is countered by Pitt’s three-pronged fork, which is a symbol of Britain’s strength on the seas. So too are their outfits and regalia highly important in easily identifying these characters and the relationship between them. Gillray composed this cartoon to satirically comment on Napoleon’s attempts to forge peace with Britain during the War of the Third Coalition, which were seen as insincere. Hauntingly, the cartoon’s original caption warns that the globe is not big enough for the power appetites of these rulers. Indeed, it was not, as the war only intensified following the cartoon’s release.

The Third of May 1808 (1814) by Francisco Goya

| Artist | Francisco Goya (1746 – 1828) |

| Date of Artwork | 1814 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 268 x 347 |

| Housed | Museo del Prado, Madrid, Spain |

Francisco Goya requires little introduction, and his art was almost always political. In a reverse career path to Jacques Louis-David, Goya began his career as a royal court painter but later dived into a more personal period which is as much political as it is moving. Ever since falling deaf in 1793, Goya’s work began to take on darker and more contemplative themes, as he began reflecting on society in the midst of his own physical and mental sufferings. This change in tone was sparked when Spain was invaded by France in 1808. Goya remained court painter and was commissioned to produce works for ruling French incumbents, but remained neutral throughout this period. In secret, Goya worked on a collection of political artworks inspired by his experiences during this time. These works were only published 35 years after Goya passed away in 1863, mainly because they were too critical to be released any time before.

Alongside the series of etchings The Disasters of War, Goya produced a pair of companion political paintings, The Second of May 1808 and The Third of May 1808 in 1814.

These paintings were inspired by the Second of May Uprising, where poor Spanish citizens conducted a spontaneous rebellion against the French military in Madrid. The military brutally repressed this uprising and hundreds of Spanish lives were lost. The first painting depicts the uprising in motion, while the second attends to the numerous executions which followed it. Goya’s commitment to artistic neutrality and realism remains clear, and by providing these scenes of violence with such moving darkness and intensity, historians suggest that these works were political statements against such wanton violence. In the first painting, Goya depicts the rebelling Madridians as heroes standing up against a professional army – knives against guns. This upset the returning Spanish king, which is another reason for its delayed release to the public. Also note how Goya does not prioritize any specific point of focus, this in order to accurately capture how chaotically these events played out.

The Third of May 1808 is often grouped among the first Modern paintings in art history. Breaking with all former conventions about how scenes of war and death should be depicted, this piece was revolutionary for art as a whole. Goya’s treatment of light in this scene is of particular importance. The lantern does not only shed a dramatic light and color on the main figure of the scene, the laborer protesting his innocence before execution, it also presents the French shooting squad as one morphed unit, thus serving as a soft border between good and evil. The worried onlooker waiting in line serves to guide the viewer’s gaze across the two lines of soldiers and victims. Some note the influence of Peter Paul Rubens in this painting, especially in Baroque elements of emotional intensity.

Man at the Crossroads (1933) by Diego Rivera

| Artist | Diego Rivera (1886 – 1957) |

| Date of Artwork | 1933 |

| Medium | Fresco |

| Dimensions (m) | 4.85 x 11.45 |

| Housed | Replica in Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, Mexico |

Diego Rivera was a revolutionary Mexican painter whose impact remains prevalent today. His career as an artist took him around the world, from his home country to France and later the United States. His works were known for their charged political engagement, philosophical consciousness, and intricate details. He was married to Frida Kahlo for some time, who produced a number of political artworks in her own right, centralizing Mexican cultural heritage and the sidelining of women in art. One such work is Moses (1945). Rivera was keen to depict his political and philosophical musings onto canvases and murals. He was inspired by the history and struggle of both his own people and other groups around the world, as evidenced by political artworks such as The History of Mexico (1935) and Detroit Industry Murals (1933).

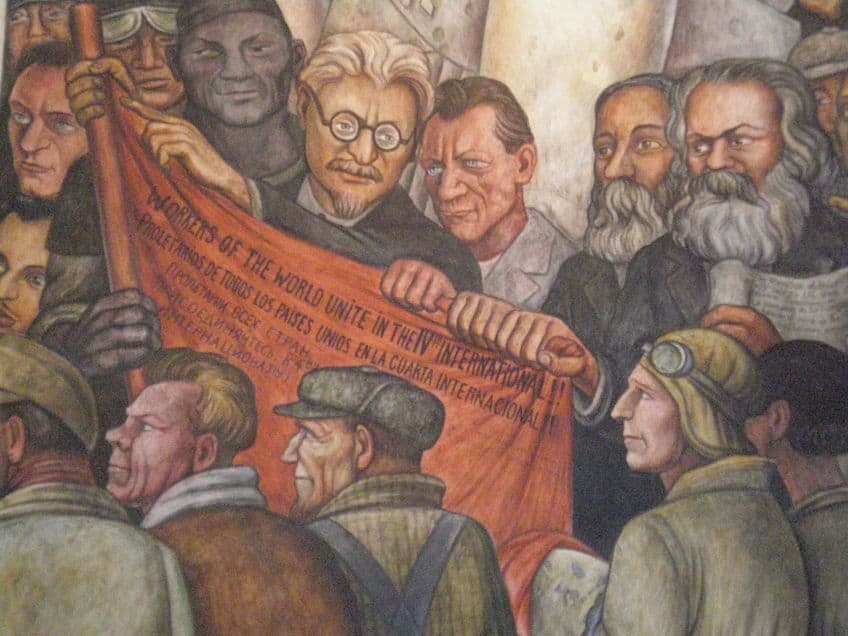

Man at the Crossroads is as much a political artwork as it is a political actor.

The piece was originally commissioned for the foyer of the Rockefeller Center’s main building in 1932. Rivera was at this point one of the most famous painters in the world, let alone one of the most famous political artists. In what is heralded as one of the greatest political artworks of the 20th century, Man at the Crossroads was a piece in which Rivera allowed his most potent creativities to flourish. The painting was a 5 by 11 meter mural divided into three panels, each representing different stages of humanity’s unfolding progress through history. The left-hand panel concerned the development of ethics and science, with its opposite portraying the development of economics and equality. The central panel united the mural by depicting a worker controlling this evolution with a complex machine, undercut below by a flourishing nature out of which all life emerges.

But how was the painting a political actor as well? In what has come to be known as the “Battle of Rockefeller Center”, the piece sparked a conflict between artists and art houses all over the world after being rejected. The piece was admired by the Rockefellers but the issue lay in the representation of Vladimir Lenin in the bottom right section. This was a time of anti-radical skepticism in the United States, and communist symbolism had little place in the censored art scene of the time. Rivera refused to remove the Soviet leader from the painting, but offered to repaint the work in any other building. To no avail, this treasure of famous political art was thus carelessly destroyed as the foyer wall was plastered back up. Artists all over the world criticized the decision and protested, fundamentally shifting standards of artistic freedom in the art world. Today, it is unlikely that the fresco would have been destroyed in the way that it was. A recreation exists in Mexico at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, but the original artwork remains lost to time, only living through a few photographs taken before its destruction.

Guernica (1937) by Pablo Picasso

| Artist | Pablo Picasso (1881 – 1973) |

| Date of Artwork | 1937 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 349 x 776 |

| Housed | Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid, Spain |

Although often valued more for his deft skill and unique artistic contributions, the political paintings of Pablo Picasso’s oeuvre should not be overlooked. The political threads that flowed through his works were subtle and complex, but moving nonetheless. Picasso produced a number of political paintings throughout his career, the most overt of which arrived after his experiences in the Spanish Civil War. He initially mobilized political propaganda in art for the Republicans in the war, The Dream and Lie of Franco (1937) being one notable example. Thereafter his political art took on more personal inspirations, allowing his limitless creativity to envelope this genre as well. There are three main anti-war paintings produced by Picasso: Guernica (1937), The Charnel House (1945), and Massacre in Korea (1951).

With each, Picasso offered incomparable artistic interpretations of some of the most important political events of the 20th century.

Guernica is historically considered as a critically important anti-war painting. Like Goya, Picasso sought to critique war by drawing attention to the suffering and atrocity it brings with it. The painting was produced in response to the bombing of the town of Guernica by fascist forces in 1937. The town of Guernica was mainly housing women and children as most men were away fighting. The events hurt Picasso in more ways than one, not only as a Republican supporter but as an artist who had always taken women and children as humanity’s perfect forms. The characters in Guernica reflect these events as women wail in fear or sorrow, with one holding her deceased child in her arms. The painting is taken as a flagship for Picasso’s cubism, making use of broken-up geometric shapes reassembled into abstract arrangements.

The scene is set in a dark room, with another door to the right of the room leading further into darkness. Picasso’s careful use of shading and color in black, gray, and white conveys a mournful tone. A horse suffers above a fallen soldier, reminding the viewer of the main topic of the painting, which is war and all its agony. A bull in the left of the painting, whose tail has been manipulated to resemble smoke, has sparked countless theories about Picasso’s intended symbolism, although the artist himself never revealed his direct intentions for the figure. There is also hope, however, but only in the transcendence of the violence of war. For instance, a flower grows from the fallen soldier’s sword, and a dove is seen through a crack in the wall, in a bright and peaceful world outside of the darkened room of war. A ghostly head and arm of a woman floating above carries a torch of peace across the scene, bringing light with it. The massive painting was later displayed across Europe, raising funds and bringing attention to the Spanish Civil War. In many ways then, Guernica is an early example of activist art.

The Migration Series (1941) by Jacob Lawrence

| Artist | Jacob Lawrence (1917 – 2000) |

| Date of Artwork | 1941 |

| Medium | Tempera |

| Dimensions (cm) | 30 x 46 |

| Housed | Museum of Modern Art, New York and The Phillips Collection, Washington D.C., United States |

Jacob Lawrence was a prominent American painter whose groundbreaking interpretations of the African-American experience in the early 1900s have left an indefinite impact on politically engaged art. Lawrence grew up in Harlem after moving from New Jersey at 13. Attending art classes throughout his youth, he was enamored by the busy and diverse color schemes of his surroundings. Even though he dropped out of school at 16, his passion for art saw no interruption.

By 1937 he was studying under some of the leaders of the Harlem Renaissance, on his way to his own success.

Lawrence swayed little from his main topic of choice as an artist, namely the social life of Harlem and African-Americans on the whole, who were experiencing significant struggles at this point of the 20th century. Lawrence saw a prime muse in the Great Migration, which saw over 6 million African-Americans relocate northwards from the south in the early 1900s. At the age of just 23, he produced a 60-panel artwork depicting the social and cultural changes the migration brought along with it. Lawrence grew up around people who were part of the Great Migration, and so had an intimate grasp on the social aspects involved.

Lawrence produced The Migration Series in the same style that had already brought him attention as an upcoming artist – what he called “dynamic cubism”. This cubism was inspired by the rich colors of Harlem, straying from classical cubism in its use of patterning, brightness, and sharper shapes. Using tempera as a medium, Lawrence planned and painted all the panels at once so as to maintain color consistency throughout the artwork. His work inspired other polemic works of art concerning the social struggles of African-Americans, such as Norman Rockwell’s The Problem We All Live With (1964).

Watercolor of Terezin (1944) by Petr Kien

| Artist | Petr Kien (1919 – 1944) |

| Date of Artwork | 1944 |

| Medium | Watercolor on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 45 x 35 |

| Housed | United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington D.C., United States |

The Second World War oversaw countless works of famous political art, some produced as part of the war effort, others in fiery critiques of the war itself. One of the most touching political paintings from this period, however, for both its composition and the context in which it was produced, is Petr Kien’s Watercolor of Terezin. It is one of many works produced by Kien before his early death at 25. Kien was a talented Jewish artist from Czechoslovakia who produced thousands of paintings, poems, operas, plays, and drawings in his short career. He had risen in popularity at the Academy of Fine Arts in Prague leading up to World War Two. But in 1939 after the Nazi’s Nuremberg laws were enforced, Kien and his family were deported to the Terezin Ghetto. Terezin served as a halfway point for established Jews before being sent to concentration camps around Europe, but was covertly portrayed by the Nazis as a free Jewish settlement.

Alongside Kien, a number of prominent Jewish artists were imprisoned in the ghetto with which he collaborated.

Kien was assigned as leading technical drawer at the ghetto, but almost upon arrival began to sketch the scenes of suffering that circulated around him instead, working with stolen stationery and paper. The Watercolor of Terezin is one of many still-lifes that he produced depicting the ghetto. In it, he leaves space for hope in the face of evil by making use of dynamic and flowing color. This lay in stark contrast to the poetry he was producing at this time, which was far darker. Watercolor of Terezin and Kien’s similar works from the ghetto were not just political because of their content, but because of the social impact they had. These artworks were vital in exposing the brutality of Terezin to the rest of the world after the war, and contributed directly to providing an accurate historical record of the Holocaust. Kien would unfortunately never see his great impact, as in the same year he produced this work he was transferred to Auschwitz and died thereafter.

Some say that he was sent to his death after the Nazis discovered some of his works, particularly the critical opera Emperor of Atlantis (1943) he wrote with Viktor Ullman. Other sources state that Nazi officers broke his hand before his deportation to Auschwitz – clearly, both he and his art were a political threat. We have no doubt that Kien would be pleased to know that his works did much to reveal the atrocities of the Holocaust, leaving his mark on history.

The Dinner Party (1979) by Judy Chicago

| Artist | Judy Chicago (1939 – Present) |

| Date of Artwork | 1979 |

| Medium | Mixed media |

| Dimensions (m) | 14 x 14 x 14 |

| Housed | Elizabeth Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Brooklyn Museum, New York City, United States |

Judy Chicago was a highly influential political artist at the forefront of the early feminist movement. While at university, she attempted to produce artwork depicting sexual organs and feminist ideals, but was repressed by her professors for her radicalism. As a result of her artistic growth and the death of both her husband and father, she changed her last name from Cohen to Chicago to turn a new independent chapter in her life. Throughout the 1970s, Chicago established herself among the world’s finest feminist artists. At this time she also became a lecturer, giving courses in feminist art to the next artistic generation. Following her success with Womanhouse (1972), a participatory political art exhibition centered around women’s empowerment, Chicago shook the art world with her magnum opus, Dinner Party (1979).

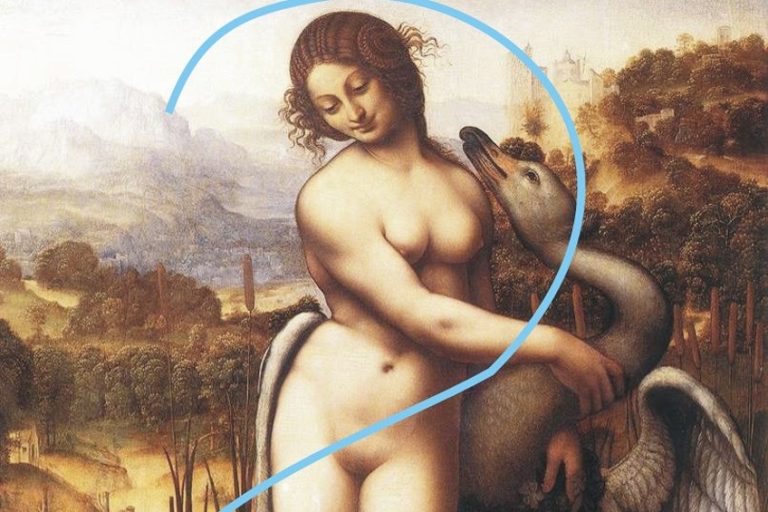

Dinner Party posits a massive triangular dinner table with a shallow body of water enclosed by it. On the tabletop, 39 seat placements are carefully arranged for 39 women identified by Chicago to have influenced human history, be they living, dead, or even mythical. Each plate is sculpted uniquely in shapes representative of a vulva. This group includes ancient goddesses, important religious figures, artists, writers, scientists, and women’s activists.

Some notable attendees of the dinner party are Georgia O’Keefe, Sacajawea, Susan B. Anthony, Hildegarde von Bingen, Sappho, and the female Egyptian pharaoh Hatshepsut.

Beneath the dinner table lies a floor of porcelain tiles engraved with the names of another 998 influential women in history. One man was mistakenly included, the Ancient Greek sculptor Kresilas, who at the time was historically thought to have been a woman. Chicago took cues from both her own feminist art and the artworks of the past. For instance, the choice of a triangle is a feminist symbol for equality, whereas by segmenting the table seats into groups of 13, Chicago is alluding to the Last Supper, at which no women were present.

It took over 6 years and 400 individuals to produce this masterpiece, although for the first 3 years, Chicago worked on the project alone. The dinner plates gradually increase in tilt between seats 1 and 39, acting as a symbol for the gradual gains women have made towards equality and independence throughout history. The piece served as a critique of the common exclusion of women from the mainstream historical record.

Chicago figured her art as a political statement by highlighting women who changed history, making a political claim about how we should understand history and who should be included in it.

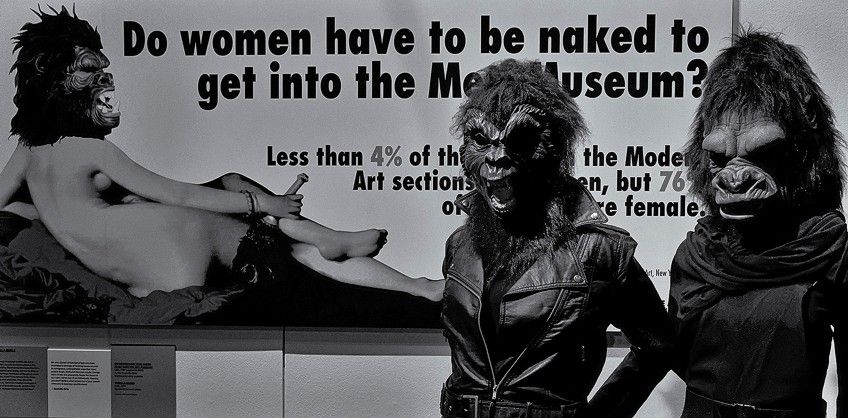

Chicago paved the way for feminist artists both in her time and for those thereafter. For example, the Guerilla Girls followed in her footsteps as a group of anonymous feminist artists bringing attention to sexism rooted in the art world, and are still active today. Their postered question from 1989 remains relevant: “Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum”?

Girl with Balloon (2002) by Banksy

| Artist | Banksy (1973 – Present) |

| Date of Artwork | 2002 |

| Medium | Stencil mural |

| Dimensions (cm) | 101 x 78 (Paper reproduction) |

| Housed | Waterloo Bridge, London, United Kingdom |

We can think of Bansky as both a political artist and a political activist. But it may be smart not to say too much about Banksy at all, seeing as we know very little about him in the first place. One of his main claims to fame is his secrecy and anonymity as an artist. Most people still do not know who Banksy is, let alone his real name. Regardless, his social issue art stands up among the most influential, both past and present. Banksy is known for his famous political art, mainly striking and sometimes humorous stencil graffiti works which can be found all over the world. All his works are politically engaged art, providing viewers with opportunities for personal reflection. His topics include war, inequality, consumerism, authoritarianism, and greed, among others.

It is difficult to isolate any one of Banksy’s paintings as his most influential, because his repertoire extends into thousands. Nevertheless, the two works stand out as directly political, either for their content or the way Banksy has engaged with art and society through them.

Rage, The Flower Thrower (2005) was produced by Banksy on his travels to the war-torn West Bank, stenciled upon the 760-kilometer wall that separates Israel and Palestine. In the painting, a Palestinian protestor is depicted throwing a projectile replaced by a bouquet of flowers. This is a clear example of Banksy’s sentiments regarding war, and his dreams for peace. Another one of Banksy’s most recognizable political artworks is Girl with Balloon (2002), initially produced at a number of sites across London in 2002. The piece portrays a young girl with a balloon, and Banksy leaves it up to the viewer to determine whether the girl is reaching out for the balloon or has just lost grasp of it. The balloon takes upon a heart shape and is the only part of the image that has color, intended to symbolize hope. Banksy plays on notions of innocence to provoke feelings of optimism and hope in the world with a childlike simplicity.

Ever since its initial appearance, Banksy has produced multiple recreations of the piece to accommodate different political agendas, such as raising funds for victims of the Syrian War and vocalizing his views against Brexit. He took the political life of this artwork even further at an auction at Sotheby’s London in 2018. After a framed copy of the piece had just sold for over a million dollars, a paper shredder secretly built into the frame by Banksy shredded the work, effectively destroying it. The mechanism failed to complete the process, shredding the work up to its halfway point and leaving only the heart-shaped balloon in the frame. This then became an art piece of its own, and remains the only artwork produced during a live auction. In 2021, it sold for 25 million dollars. In this process, Banksy challenged the fabric of what artworks can be and how the art world receives them – a political comment in its own right.

Sunflower Seeds (2010) by Ai Weiwei

| Artist | Ai Weiwei (1957 – Present) |

| Date of Artwork | 2010 |

| Medium | Porcelain |

| Dimensions (sq m) | 1000 |

| Housed | Tate Modern Museum, London, United Kingdom |

Ai Weiwei is a prolific Chinese artist and political activist known for his creative and famous political art. Following a difficult childhood under conditions of political repression, Weiwei began his artistic career in film before moving to the United States and gradually staking his claim as a talented multi-medium artist. He has since produced a plethora of social issue art, encompassing documentaries and music, to visual art and architecture. Weiwei has never been one to reserve his political views, and has channeled his criticism of the Chinese government by utilizing his art as a political statement. This is inspired by his experiences of hardship growing up in the country and his emphasis on individuality, democracy and human rights. He has investigated a number of national scandals, and has even been arrested twice for his critical artistic voice.

Sunflower Seeds (2010) is a conceptual installation artwork first exhibited at Tate Modern art gallery at the start of the 2010s.

The artwork consists of one hundred million small porcelain sculptures, carefully designed to resemble sunflower seeds. This incomparable hand-crafted artwork required the skill of over 1600 artists working together for two years in the town of Jingdezhen, China’s home of porcelain crafting. Audiences could initially interact with the seeds by touching, sitting, and walking on them until fears of their decay saw the piece cordoned off.

There are multiple inspirations behind this famous political artwork. Personally, Weiwei sees the sunflower seed as a symbol of togetherness during challenging times, as they were always shared between friends while he was growing up. Politically, Sunflower Seeds is a comment on China’s magnitude, and how the individual can be forgotten amidst vast expanses of conformity, much like how individual seeds are easily lost when viewing the artwork in full. It is also a critique of mass consumer culture and attempts to bring new perspectives to what it means for something to be “Made in China.”

Political art is a highly complex and varied artistic genre. It is related to the different contexts in which it is rooted, from revolutions and wars, to social movements and changes in the concept of art itself. Politically engaged art can appear in multiple forms, but the main types of political art can be understood as portrayal, promotion, or projection. The list above has run through some of the most famous political art in contemporary history, but many remain to be explored as political artworks continue to be produced everyday.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why Make Political Art?

Political art relies on the premise that art has the power to spur change in the world, just as much as literature or politicians can. The list of famous political art above certainly suggests this is true. Political artists are motivated by the will to interpret or change their social realities, by expressing their views and drawing viewers to the messages they portray through their artworks, utilizing art as a political statement.

What Is Political in Art?

Any kind of art can become political depending on both the context in which it is produced, and the inspirations involved in the production of the artwork itself. At the fundamental level, art is made political when it brings awareness or instigates social change, on either the part of the artist or the viewing public. Whether or not this process is intentional does not matter, as long as meaning is recovered from the artwork and this meaning is directed towards change.

Who Are Some Other Political Artists?

There are numerous famous political artists and artworks that did not appear in our list, but deserve recognition as well. Even though your local graffiti artist can be a political artist in their own right, famous political artists (and their influential political artworks) that eluded mention above include: Ai Weiwei (Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn (1995)), Chris Ofili (No Woman No Cry (1998)), Alberto Korda (Che Guevara (1960)), Shepard Fairey (Hope (2008)), Barbara Kruger (I Shop Therefore I Am (1987)), Max Ernst (Europe After the Rain (1942)), and Yoko Ono (Cut Piece (1964)).

Armin Kific is a social and political researcher and writer based in Pretoria, South Africa. He completed a degree in Political Science with majors in History and Philosophy in 2020 and has since completed an Honours in Anthropology and History. He is also currently pursuing a Master’s degree in Social Sciences from the University of Pretoria. Armin’s knowledge of the arts spans various mediums, and he is always looking for ways to marry art with social science. In 2021, he produced a short documentary film about the often-forgotten South African soul star Mpharanyana, integrating history, music, photography, and film. Armin is well-versed in art history, especially in the fields of political artwork and ancient artifacts. He enjoys exploring art history sources for information that has been lost or overlooked. He is also trained in biographical writing.

His favorite art movements include baroque, surrealism, and neoplasticism. Armin is an ardent supporter of indigenous art in South Africa and is involved in an organization that looks to uplift South African artists following the challenges of Covid-19. By writing for ArtInContext, Armin continues to cultivate his artistic creativities and unite perspectives between art and society.

Armin has been working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He writes about the topics of art history, specializing in political artworks and ancient artifacts.

Learn more about Armin Kific and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Armin, Kific, “Political Art – How We Use Art As a Political Statement.” Art in Context. June 2, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/political-art/

Kific, A. (2023, 2 June). Political Art – How We Use Art As a Political Statement. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/political-art/

Kific, Armin. “Political Art – How We Use Art As a Political Statement.” Art in Context, June 2, 2023. https://artincontext.org/political-art/.