Winslow Homer – The Life and Paintings of the Famous Watercolor Artist

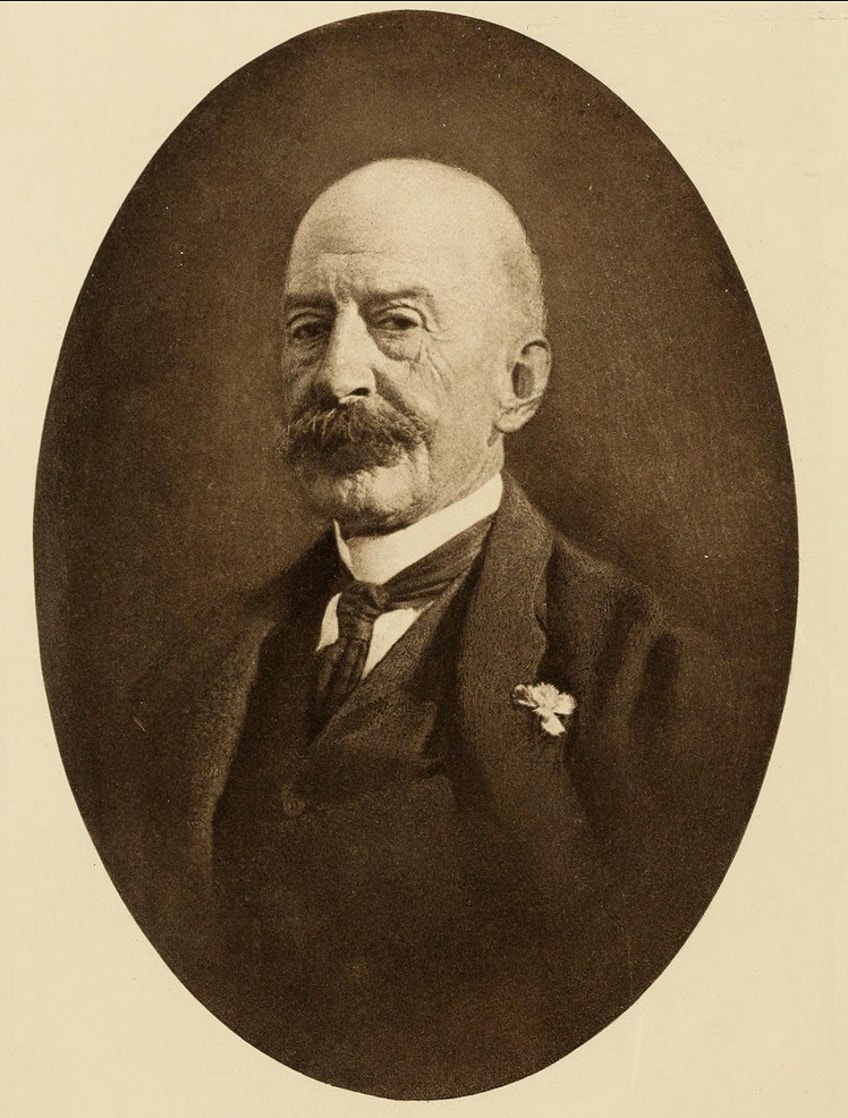

Winslow Homer was not only a watercolor artist but was also adept at oils and sketching. Winslow Homer’s paintings of marine subjects, such as The Gulf Stream (1899) were regarded as very expressive and powerful for the era in which they were created. The topics of Winslow Homer’s artwork, while seemingly simple on the face, grappled with the issue of human suffering within an uncaring cosmos in their most intense scenes. Today we will be exploring the most interesting Homer Winslow facts dealing with his life and art.

The Life and Art of Winslow Homer

Winslow Homer was enthralled by the immense grandeur of nature and wanted to convey that sensation onto his compositions through the brilliance of his expressive brushwork. Nature’s force is both grand and everlasting in Homer Winslow’s paintings and nonchalantly disinterested in the dramas of the human condition. The raw manner of these final years was not an aberration, but rather a distinctive feature of Winslow Homer’s artwork in its entirety.

| Nationality | American |

| Date of Birth | 24 February 1836 |

| Date of Death | 29 September 1910 |

| Place of Birth | Boston, Massachusetts |

Childhood and Education

Winslow Homer’s mother was a hobbyist watercolorist who introduced her creative son to the basics of her discipline; their mutual love of the arts created a strong bond that endured throughout their lives. His father was a generally unsuccessful businessman with an eccentric demeanor. Nonetheless, he was supportive of his son’s creative pursuits.

On a business trip to England, he also fostered his son’s “inclination toward painting” by purchasing for him “a whole series of lithographs by Julian – depictions of facial features, trees, homes, anything that a youthful draughtsman would envisage having a go at.”

Furthermore, when Winslow was 19, his father organized for him to begin an internship with a friend, John H. Bufford, a notable lithographer in Boston. Despite the fact that this era represented the closest approach to professional instruction, designing drawings for popular sheet music, Homer would later characterize these years as being a “treadmill life.” After finishing his apprenticeship in 1857, he swore he would never work for anyone else again, started his own workshop in Boston, and developed a thriving freelance business as a commercial artist.

Homer swiftly rose to prominence, making pieces for publications in Boston and New York, but he soon revealed his actual aspirations: becoming a painter.

Early Career

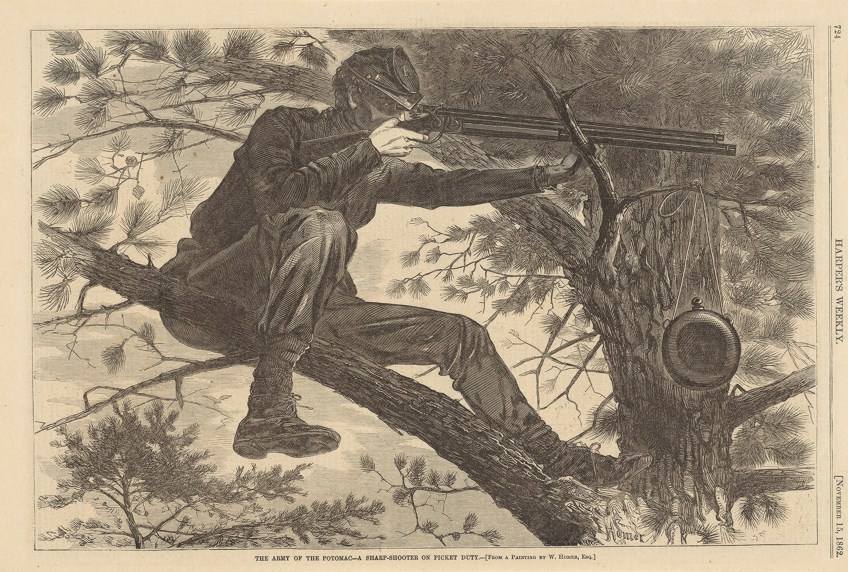

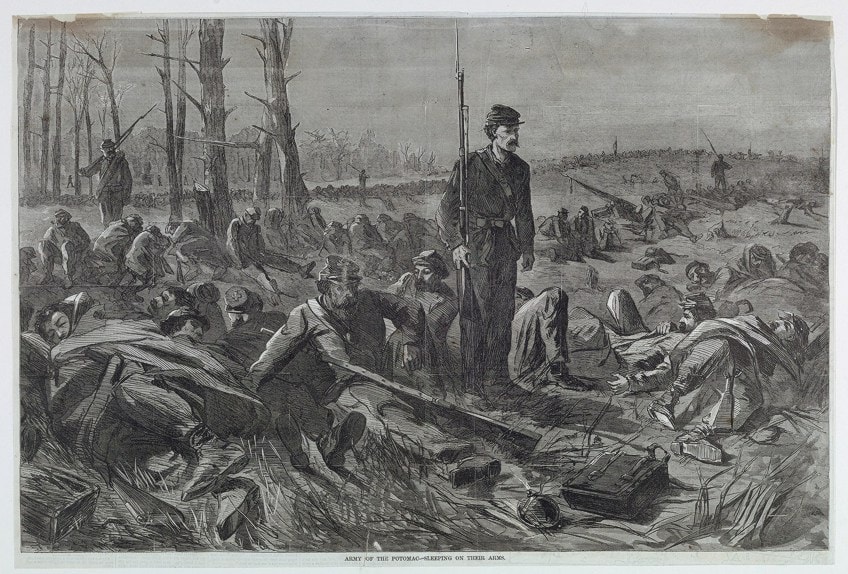

Winslow Homer’s early employment as an artist exposed him to the reality of the Civil War. After six months of the war’s commencement, Harper’s Weekly dispatched Homer to the front lines to document the conflict, which became a watershed moment in his psychological and creative growth. During his repeated travels to the Northern forces’ camps, Homer made various sketches for engravings spanning from genre settings to cluttered scenes of warfare.

Nonetheless, it was his subtle portraits of the ordinary life of average troops that dominated his output during this time period.

These sketches eventually served as the foundation for his professional illustrations and, presently, offer a unique perspective on the developing technology of contemporary warfare, most prominently in his series The Army of the Potomac (1862).

After the war, Homer’s wartime sketches continued to inspire a series of paintings, most notably Prisoners from the Front (1866), which established his name as a painter and continue to be among his most well-known works to this day. These works established his artistic name in New York, and he was selected to exhibit at the 1866 Exposition Universelle in Paris.

Despite his popularity, Homer continued to create commercial works until 1875, when he shifted his focus to being an oil and watercolor artist.

Mature Period

Homer came to France with his painting in 1867 for the first of two voyages to Europe and stayed in Paris for over a year. The youthful American’s visit to France corresponded with exhibits of Realist painters such as Gustave Courbet and Edouard Manet. Homer was more inspired by The Barbizon School, a scape style that gained prominence in America in the 1860s. During his visit, Homer would have encountered the pre-Impressionist works of Auguste Renoir and Claude Monet, who looked just as captivated by the qualities of lighting as their counterpart from America.

There was a feeling of yearning and naivety mixed in with a uniquely American embodiment of contemporary, democratic principles in Winslow Homer’s artworks upon his return.

Even in this early stage, the manner of his writing irked reviewers of the day, with some describing it as “incomplete,” and has long baffled anybody attempting to draw a genealogy between Homer and older masters. “If a gentleman wants to be a painter, he must never look at images,” says Homer, encapsulating his objective of artistic freedom.

As a result, without embracing the aesthetic appeal or urban tendencies of the “sophisticated” trends in French artwork, Homer started painting pictures of remote American life in his distinct aesthetic, such as a series of works depicting images of village schoolchildren operated by young school teachers and perceptive genre depictions of African Americans.

Despite his continuous increase in popularity, the critical response to his work has been varied. “We candidly admit that we despise his subjects, he has selected the lesser pictorial variety of landscapes and culture; he has determinedly handled them as if they were stylistic,” one critic wrote of his creations, while others lauded his uniqueness: “There is no image in this showcase, nor can we recollect when there has been an image in any art show, that can be compared next to this.”

Around 1880, Homer began to withdraw from metropolitan social life in favor of a calmer existence in small towns, relocating to an island in Gloucester Harbor for the summertime. Some assume that this was due to a succession of personal tragedies or other emotional anguish, but such speculation is impossible to substantiate because Homer guarded his private affairs very secretively.

“It would definitely kill me to have such a thing surface – and as the most intriguing portion of my existence is of no relevance to the world, I must reject to offer you any specifics in reference to it,” he reportedly said informed a potential biographer.

Regardless, the change of setting had a considerable influence on the subject matter of his paintings, which became more dramatic and even gloomy during this time.

Late Period

Almost every author who has written on Homer since 1882 has seen the voyage to England as a watershed moment in his life, separating his promising earlier years from his more mature phase, when he would bring a new degree of passion and intent to his craft. Subjects of Winslow Homer’s artworks turned toward the working classes, most commonly fishermen and females whose lives were both divided and connected by the sea.

Homer caught the dramatic fog-lined beach while presenting situations in an emotionless manner, leading art historians to consider works from this time as portrayals of regular laborers’ daily heroics.

Although Homer continued to exhibit his work in New York for the remainder of his career, he elected not to reside there when he returned to America. The craving for solitude that drove Homer to spend almost a year and a half in Cullercoats followed him to America. Prout’s Neck, a rugged headland on the coast of Maine provided him with an adequate setting.

The watercolor artist had spent over ten years visiting the lonely location before settling to Prout’s Neck. Homer purchased the carriage house of his brother’s main house, where he established his artist workshop with a sea view beyond the steep cliffs.

His most famous works from this time period may reflect a life of seclusion and forbearance.

During the winter months, Homer is known to have ventured far from the icy northern shores of Prout’s Neck for the milder climates of the Bahamas, Bermuda, and Florida, capturing the particular atmosphere of the tropical environment in a succession of watercolor paintings and drawings. Homer, on the other hand, would return to his workshop above the rugged seashore cliffs and resume his tireless marine expeditions. He died at Prout’s Neck in 1910 at the age of 74.

Legacy

Winslow Homer is largely regarded as one of the most important 19th-century American artists. His work played a significant role in shaping an American creative sensibility at a period when European ideas were a source of contention among American painters and critics. His steadfast individualism was a source of inspiration for people of his generation.

Homer revolutionized genre painting into powerful expressions of human taste, and in his later works uncovered an America that impressionist niceties and American renaissance fantasy completely disregarded.

Winslow Homer’s impact lasted well into the twentieth century, notably among painters who mostly ignored European-inspired abstraction tendencies in favor of pursuing a uniquely American voice in their work. It seems logical that a painter whose long career spanned several mediums, from printing to oil painting to watercolor, would have a similarly wide effect.

Winslow Homer’s Paintings

Winslow Homer’s painting career began with his realistic depictions of the American Civil War. Homer, who was initially dispatched to the frontlines as a war journalist, recorded the conflict through his prints, which ranged from violent fighting scenes to tranquil moments in the soldiers’ everyday life.

These photographs came to graphically characterize the war as “illustrated journalism” to a large chunk of the Northern States’ audience. Several of these sketches were later transformed into a series of oil paintings by Homer, revealing the artist’s understanding of the lives of Union troops.

Winslow Homer’s artwork captured the shifting waves of American life and livelihood during his lengthy career.

Where his contemporaries, such as Thomas Eakins, focused on the heroic characters of sportsmen, surgeons, and academics, Homer attempted to depict key motifs through the games of country schoolteachers, windswept terrain, and coastlines, and the robust forms of fishermen men, and women. Mortality themes recur throughout Homer’s work, from his early Civil War paintings through his mid-career hunting series and, eventually, his late sea meanderings.

Homer’s apparently simple pieces, often classified as “heroic” and “manly,” frequently showed perilous circumstances and served as heartbreaking reminders of the frailty of life.

The Veteran in a New Field (1865)

| Date Completed | 1865 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 61 cm x 96 cm |

| Current Location | Metro Museum of Art, New York |

This picture, one of the most well-known of Homer’s Civil War works, illustrates the artist’s acute awareness of the socio-historical epoch in which he existed. With a scythe, a worker harvests the apparently endless field of wheat. A Union soldier’s coat and flask in the lower right corner indicate that this peasant is also a Civil War veteran. This is an early illustration of Homer’s capacity to interweave delicate storylines into his works, painted just after the tragic war’s end and President Abraham Lincoln’s following death.

In terms of creative approach, Homer’s painting appears to merge Realist and Impressionist approaches in a distinctly American manner.

The soldier’s laboring figure, portrayed in a somewhat naturalistic way, portrays the single figure’s hard struggle under the blazing sun as he sweeps his blade across the wheat. The wheat, by contrast, reads as Impressionist, despite the fact that this picture predates the origins of the Parisian style or Homer’s voyage to France.

It had been Homer’s habit to create outside long before he traveled to France, therefore Impressionism – even if he was aware of it – could not have exposed Homer to the technique of open-air paintings. It has been a major aspect of his artistic process from his early days as a painter.

Snap the Whip! (1872)

| Date Completed | 1872 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 56 cm x 91 cm |

| Current Location | Metro Museum of Art, New York |

One of Homer’s most renowned paintings poses a challenge to current observers. It looks to be a simple and beautiful sight, with a row of youths walking hand in hand and sprinting through a field of grass in an unbelievably vivid Kelly green sprinkled with wildflowers of all colors. A modest red schoolhouse sits in the distance, against a patchwork sky of blue and white.

The picture appears sad, even nostalgic, which is maybe unexpected when considering one of the most renowned American artists of the 19th century.

Even Homer’s most bucolic paintings, however, surpass nostalgia when one looks closely and notices traces of destitution, such as the children’s torn and ill-fitting clothes, and exposed feet. Childhood and the existence of children took on special relevance in America in the years after the Civil War, and these pictures reflected the resolve to reconstruct and to establish a better and more powerful nation.

The underlying storyline of these post-war pieces, which center on the experiences of youthful instructors and their pupils, is provided by veiled references to the lost generation of Civil War warriors.

The Cotton Pickers (1876)

| Date Completed | 1876 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 61 cm x 96 cm |

| Current Location | Los Angeles County Museum |

In an era rife with racist imagery, Homer went to Virginia in the 1870s to start work on a collection of works representing the lives of persons just liberated from enslavement but still battling entrenched racism. He captures calm moments in the ordinary life of newly emancipated African-Americans rather than stereotypes.

There is no overarching moralistic narrative or story plot that the artist provides, rather, like in “Snap the Whip!”, Homer conveys the sense of a witnessed moment in time.

During harvest season, two women stand in a large cotton field, their daily toil can be observed in the hefty burden each carries. The two individuals’ gigantic stature is evocative of Jean-François Millet’s impact, as is the rose-colored dusk sky, which the French Realist frequently used in his compassionate portraits of rural work.

As Homer produced this series during the latter years of the Reconstruction Period, with the evacuation of federal soldiers from the South likely to follow with the passage of the Compromise of 1877, the time of day becomes a symbol for the epoch.

However, Homer’s attitude to these works of art is not instructional.

Although painted in a concerto of pastel colors and contrasted with soft white cotton bulbs, this image does little to reassure the destiny of these women. Rather, like this and many other pieces of the age, Homer leaves the destiny of the individuals to the viewer’s imagination.

Mending the Nets (1882)

| Date Completed | 1882 |

| Medium | Watercolor |

| Dimensions | 69 cm x 49 cm |

| Current Location | National Gallery of Art, Washington DC |

The elegance of the native way of life piqued his curiosity and provided him with a fresh set of genre images vaguely tied to his growing interest in marine themes. The work’s extraordinary degree of detail, particularly in the individuals’ hair and the fishing net, demonstrates Homer’s mastery of the challenging medium.

The women are dressed shabbily and are intent on their labor, in stark contrast to Homer’s prior compositions of refined women engaging in pleasurable pursuits.

It was the manner of Homer’s English era, more than the topic, that seemed to catch his reviewers off surprise, with one remarking in the New York Times: “In both technique and style, they are English. Before thinking that the maker of those English watercolors is just the same who used to excite the fury or admiration of reviewers with his funny conceits, blatant peculiarities, and gorgeous recordings of situations that only he knew how to paint, one must read the signed name.”

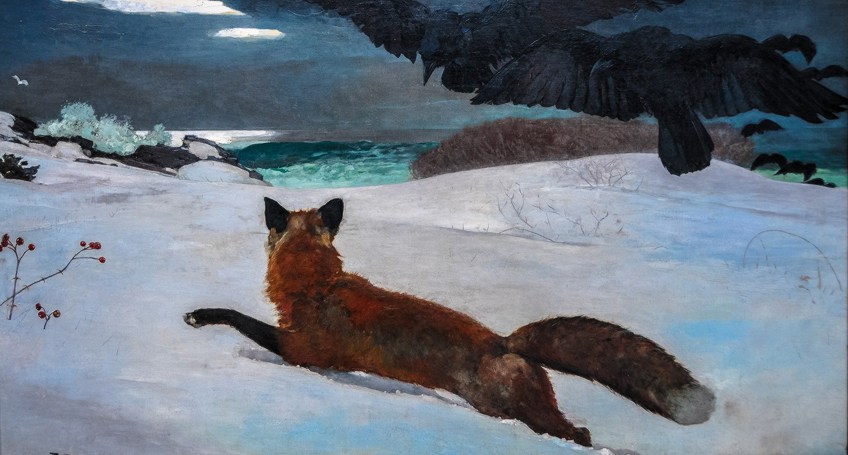

Fox Hunt (1893)

| Date Completed | 1893 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 96 cm x 174 cm |

| Current Location | Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts |

Fox Hunt, Homer’s biggest painting, is a good illustration of the topics he focused on in the 1890s when he mainly abandoned portrayals of men and women laboring in and engaging with nature. Instead, the artist concentrated only on depicting the natural environment. In this painting, he depicts a starving fox struggling to survive an onslaught by a swarm of ravenous crows.

The crows tower enormous overhead, while the fox is portrayed mid-stride, but plainly hindered by the heavy winter snow – the entire composition lends the painting a feeling of magnificent urgency.

In this scene, the conventional roles are flipped, as the fox that normally hunts here becomes the prey. The suffering creature’s claw extends out, pointing to the sole indication of life, vivid red berries, a toxic kind, starkly set against the freezing white snow. A reference, maybe to one of the scene’s expected outcomes.

Nevertheless, the fox’s sharp diagonal, which is mirrored by the artist’s name in the lower-left corner, implies mobility for the animal and helps the observer to deduce the outcome of this dramatic event.

Recommended Reading

We hope you enjoyed these Winslow Homer facts. Winslow Homer’s paintings, such as The Gulf Stream have given us a greater insight into the lives of those working by the seas and countryside. Maybe you are keen to learn even more about Winslow Homer’s artworks and lifetime. Here are a few books to help you achieve that goal.

The Watercolors of Winslow Homer (2001) by Miles Unger

Winslow Homer’s preferred medium was oil painting, but he also performed commercial graphics and recorded the New York City social scene to make ends meet. Homer eventually retreated from city life entirely, settling in Prout’s Neck in New England. There, he started to turn to watercolor, partly for monetary reasons, but also because the popular new medium allowed him to encapsulate his impressions of landscapes and countryside experienced from his many journeys with suddenness and straightforwardness inconceivable in the more time-consuming oil paints.

Winslow Homer: Artist and Angler (2002) by Patricia Junker

This book is accompanied by a spectacular display of paintings, including kaleidoscopic vistas of trout ponds, brightly colored prize fish, and emotive transcriptions of a sportsman’s days on crowded rivers and languid streams. The collection of images shown in our galleries at the Fine Arts Museum of San Francisco provides visitors to our respective institutions with a brief but unforgettable view into Homer’s realm, the realm of the Victorian sportsman, and the battlefield of nature.

- This book accompanies an exhibition of splendid paintings.

- Offers readers a brief but memorable glimpse into Homer's world

- Accompanying the museums at the Fine Arts Museum of SF

Despite Homer’s status as the “archetypal American painter,” two different travels to Europe had a significant impact on the creator’s attitude to form and substance. In Paris, he found the Realist paintings of Jean-François Millet, and Gustave Courbet, as well as the growing interest in Japonism. Homer returned to Cullercoats, England, more than ten years later, and was struck by the lives of the women and men whose livelihoods depended on the ocean.

Take a look at our Winslow Homer paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Winslow Homer?

He was a late-19th-century American artist whose paintings, particularly those on sea topics, are among the most dramatic and expressive in the country. His expertise in drawing and watercolors adds the exhilarating immediacy of empirical observation from the environment to his oil paintings. His themes, often seemingly simplified on the surface, dealt with the theme of human struggles within an unsympathetic world in their most dramatic moments.

What Was Important About Winslow Homer’s Artwork?

Winslow Homer was well-known for working in a number of art media, unlike many other painters who were well-known for working in only one. Marine scenes were frequently represented in Winslow Homer’s paintings. Winslow Homer’s paintings showing coastlines and coastal vistas evolved when he spent the years 1881 to 1882 in the town of Cullercoats. Working men and women from the area are seen in several artworks from the English coast.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Winslow Homer – The Life and Paintings of the Famous Watercolor Artist.” Art in Context. April 21, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/winslow-homer/

Meyer, I. (2022, 21 April). Winslow Homer – The Life and Paintings of the Famous Watercolor Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/winslow-homer/

Meyer, Isabella. “Winslow Homer – The Life and Paintings of the Famous Watercolor Artist.” Art in Context, April 21, 2022. https://artincontext.org/winslow-homer/.