“Olympia” Manet – An Analysis of Édouard Manet’s Olympia Painting

It has been described as one of the “most controversial” paintings from the 19th century, you know that famous painting of a woman lying down and gazing straight at us as if she knows we are watching her. This is of course Manet’s Olympia (1863), or shall we say the most infamous painting from the 1800s? In this article, we will provide a Manet Olympia analysis and discuss the question, just what was the artist of Olympia trying to do?

Artist Abstract: Who Was Édouard Manet?

Édouard Manet was a French artist, born on 23 January 1832. He was born in Paris into a wealthy family. He was always interested in art and after enrolling in the Navy and Marines at his father’s behest he pursued his studies in art. From 1850 up to 1856 he started studying under Thomas Couture, who was a French teacher and artist. After his studies, he started his own art studio, which was in 1856. Manet was a revolutionary artist of his time, going against the traditional grain of the Salon. He was also acquainted with numerous artists and scholars, notably Gustave Courbet and Charles Baudelaire.

Manet is remembered as one of the leading artists of Impressionism, however, he was also a part of the Realism art movement and depicted scenes of modern life.

Olympia by Édouard Manet In Context

Manet’s Olympia has been the subject of numerous outrages and shocked viewers. For its time, during the 1800s, it was a painting that caused controversy because what Manet depicted was not a mythological, and therefore accepted, nude female figure, but the nude female figure of a prostitute with various suggestive objects alluding to this.

In this article, we will provide a Manet Olympia analysis starting with a contextual analysis, which will discuss Manet and his artworks in more detail to provide context for why he painted Olympia. Furthermore, we will discuss the significance of the dominant art movement Manet was involved in during his art career, which was Realism and then Impressionism.

We will then provide a formal analysis by taking a peek at Olympia and Manet’s overall subject matter and stylistic elements, for example, the color, brushwork, perspective, and scale.

| Artist | Édouard Manet |

| Date Painted | 1863 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Genre | Genre painting |

| Period / Movement | Realism, Impressionism |

| Dimensions | 130.5 x 190 centimeters |

| Series / Versions | Not applicable |

| Where Is It Housed? | Musée d’Orsay, Paris |

| What It Is Worth | Not available |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

When Manet painted Olympia in 1863 the artistic climate in Paris, but Europe mostly, functioned under traditional rules about how art should look and be. The Salon was a famous annual (sometimes biannual) exhibition, which started in 1667. It was the main exhibition for the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, or in French, Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture, which was started in 1648 by Charles le Brun.

Eventually, the Academy ended during the time of the French Revolution in 1793 and it was restarted as the Academy of Painting and Sculpture. It was combined with two other art schools in 1816, namely the Academy of Music and the Academy of Architecture. This became known as The French Academy of Fine Arts; in French, it is the Académie des Beaux-Arts.

The Salon exhibition was named after the Salon Carré, which is a room in the Louvre in Paris. It was the main location for many exhibitions, initially only for the students from the École des Beaux-Arts (School of Fine Arts) or the members of the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture to showcase their artworks.

It was a conservative exhibition space and event, although it was one of the grandest exhibitions held and was a reputable opportunity for anyone who exhibited.

However, from 1725 the Salon started exhibitions in the Louvre, mentioned above, and its name changed to Salon de Paris. Although it was more public, allowing more artists to exhibit, a jury judged the artworks from 1748. The jury was a selection of artists who were also usually selected from the Academy itself and had the know-how, so to say, about judging the artworks according to the standards of the time.

The Salon was a prestigious event and attracted scholars, art dealers, collectors, and art patrons. It was also the only large exhibition in France, and it held a level of power and control over the professional careers of artists. It followed conservative rules based on academic principles and the artistic standards, or “canons”, from Classical Antiquity.

It is important to note that during this time, art was judged according to a hierarchy of painting genres. Each genre ranked from the most “moral” subject matter to the lowest. This was about how a morally based message or story would be conveyed through the subject matter as well as how accurately the human body would be painted.

History painting was the first genre on the list. This was a genre where Biblical and mythological subject matter would depict moral messages in the best manner, and it allowed artists to paint the human form, and this is where their artistic skill also showed. The next genre was Portraiture and then Genre Paintings, which depicted everyday scenes and were also smaller in size. The other, less prestigious genres included Landscapes and Still Life Painting.

Painting as a medium was also more significant than the medium of sculpture.

Although the Salon’s history is more complex than what we have outlined above, what is important to understand from this is that there was significant conservatism and rules applied to how art should be painted and conveyed to the public – there were standards to uphold.

Therefore, when we look at Manet’s “Olympia”, which was exhibited in the Salon in 1865, we will understand the social and cultural context it was placed in.

Undoubtedly, many were shocked that this Olympia painting was not painted according to standard conventions that dictated depictions of mythological or biblical figures. Furthermore, it was a depiction of an everyday woman, more scandalously, a prostitute. It was not the accepted depiction of a classical female nude like a goddess for example. Importantly, the audience who saw this painting consisted mainly of men who were educated and in elitist circles, especially the Salon.

From Conservatism to Modernism

Edouard Manet’s Olympia became a turning point painting from the 19th century. It broke the artistic rules and portrayed subject matter and style in a new fashion. Up until that time, conservative classical conventions ruled art, but a Modern era started, this was also during the onset of the Industrial Revolution during the 18th century.

During this time there was a developing art movement called Realism, which centered around art depicting everyday life and not so much subject matter (such as Biblical and mythological) that was far removed from what the modern-day person was experiencing.

Realism was pioneered by the French artist Gustave Courbet who wanted to paint what he experienced and saw in the world. He did not follow the academic rules of art. He influenced other artists to follow new conventions, which also set the foundations for the developing Impressionist art movement.

Manet followed in the footsteps of painting within the Realist art style along with Gustave Courbet. Manet also inspired many new artists like Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, Alfred Sisley, and others, all of whom were part of the new Impressionism art movement.

Manet’s unique avant-garde approach inspired these artists to follow their own style and not the traditional conventions of academic art. However, Manet reportedly maintained his goal of exhibiting with the Salon regardless of the rejection and ridicule he underwent from his controversial paintings.

Another important figure in the move to Modernism was Charles Baudelaire, who was also a good friend of Manet’s.

Baudelaire was a French writer, poet, and art critic. He wrote several important essays around the idea of Modernism during 19th century France, especially how it implicated artists and the development of their styles and expressions, during the artistic climate of Realism and Impressionism.

Some of Baudelaire’s seminal essays include On the Heroism of Modern Life (1846) and The Painter of Modern Life (1863). Furthermore, Baudelaire and Manet used to meet at the Tuileries Gardens in Paris and spent considerable time together; Manet depicted Baudelaire in his Music in the Tuileries (1862) painting.

What was important about Baudelaire’s theories was his argument that modern life was “heroic” and that it held merit just as much as the subject matter explored from the Classical era. He placed value on the importance of the modern man and on the role of the painter who conveys the urban life that enlivens the Modern era through art. He also referred to the idea of the “flâneur”, which means “stroller” or “loafer” in English, and stated that artists need to be part of and detached from the city life. We will also notice that Manet painted himself near the far left in his Music in the Tuileries. He has been described as embodying the idea of the “flâneur”.

Baudelaire wrote that Modernity is “the transient, the fleeting, the contingent” and we see the essence of this notion in how Manet painted.

With his loose brushwork, he seemingly captures this fast-paced lifestyle of the Modern world that was so deeply dissected and revered by many scholars, writers, and artists during the 19th century. Furthermore, if we look at Manet’s Olympia painting through the lens of the Modern man at play we will have a deeper understanding of the question we posed above: what was the artist of Olympia trying to do? Manet’s expressive style of painting seemed to be inherently tied to the Modern lifestyle.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

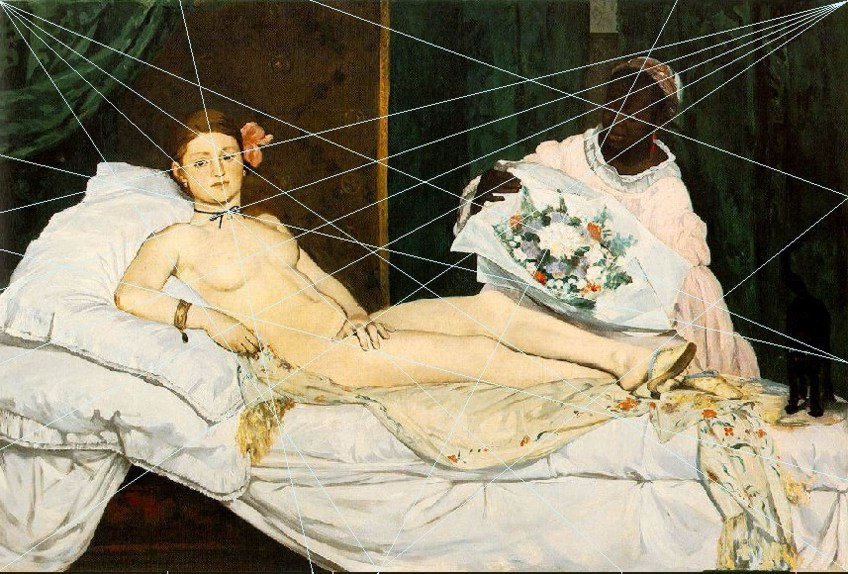

Manet’s Olympia could be considered the “poster girl” of unabashedness. She is propped up on her long chair, or as it is called in French chaise longue, staring comfortably at the viewers, which in her time would have mostly consisted of men – this could also be in the direction of an approaching client. Below, we discuss this subject matter further as well as look at Manet’s choice of artistic elements.

Subject Matter

Let us start with the central figure, who, as the title suggests, is Olympia. We see her relaxed and reclining on a chaise longue bedecked in white sheets with a creamy-colored Oriental throw or shawl over it; Olympia reclines on top of the throw holding part of it casually in her right hand (our left) as her elbow rests on the large pillow.

This gesture also hints at the idea that she does not need to cover herself and she is comfortable with her nudity.

Her left hand (our right) is placed over her genital area, her fingers resting on the top of her right upper thigh. Her legs are crossed, her left leg is over her right leg, which creates more coverage near her genital area and ironically draws more attention to it, specifically with the manner her hand is resting. However, the way her hand is placed does not appear as if she is trying to cover herself, it appears as if she is merely resting her hand in that area.

Around her neck is a delicate black ribbon with what appears to be a transparent jewel attached to it. She wears a golden bracelet on her right wrist (our left) and what appears to be pearl earrings in each ear; tucked behind her left ear is a large pinkish flower, possibly an orchid. She wears dainty heeled golden slippers with blue trimmings, the slipper on her right foot has come off leaving her foot exposed.

Olympia reclines completely in the nude and her fair skin color stands out from the darker surroundings, and almost blends in with the whites on her chaise longue with hints of gold from her jewelry and accessories as well as the throw she reclines on.

Her brunette hair is tied back and almost blends in with the darker wall colors behind her. The wallpaper behind her is darker shades of green and mustard with various patterns. To the left, we see a dark green satin curtain.

These darker shades of colors from the background emphasize the foreground, placing most of the attention on the lighter whites from Olympia and her bedding.

A close-up of Olympia (1863) by Édouard Manet; Édouard Manet, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Standing on the other side of the chaise longue, just off-center towards the right side of the composition is a maidservant presenting Olympia with a bouquet of flowers in white wrapping paper. Similarly, the maid-servant wears off-white-colored clothing, which blends in with the foreground. Her darker skin complexion blends in with the darker background colors like Olympia’s hair color.

On the end of the chaise longue, to the far right, is a black cat standing on all fours and its tail up in the air. Could the cat be depicted as either getting up from sleeping or about to lie down? The cat looks in our direction, similarly, the famous Olympia also looks in our direction, while the maidservant looks at Olympia seemingly trying to get her to look at the flowers.

Her right hand (our left) appears as if it is opening the white wrapping paper to expose the flowers a little bit more.

Who Was Olympia?

The woman reclining, who we have come to know as Manet’s Olympia, was Victorine-Louise Meurent, who was a French model and painter. She was a model for several of Manet’s paintings, including the famous Le Déjeuner sur L’Herbe (The Luncheon on the Grass) (1862 to 1863). Her paintings were also exhibited at the Salon in Paris, of which were accepted on several occasions.

When we look beyond the woman who modeled as Olympia, the actual term “Olympia” used as the title of Manet’s painting has a history of its own. “Olympia” was used to refer to prostitutes during the 1800s in France, however, there has been scholarly debate about why Manet chose this term.

The article from Sharon Flescher, titled More on a Name: Manet’s “Olympia” and the Defiant Heroine in Mid-Nineteenth-Century France (1985) suggests the term “Olympia” could have a likeness to the idea of a powerful heroic female. In Flescher’s paper, she mentions the opera Herculaneum first shown in Paris in March 1859.

The queen in the play was named “Olympia” and was a pagan queen sent to put a stop to the progress of Christianity. In the play, she also uses her powers to seduce the Christian Helios away from his lover. She also stands unwaveringly while Mount Vesuvius erupts, and lava approaches her.

Furthermore, Flescher also mentions Manet’s teacher, Thomas Couture’s painting The Romans in their Decadence (1847), and the opera Herculaneum being a “theatrical counterpart” to it. The similarities between both Manet and Couture lie in the central reclining female figure. In Couture’s painting the female reclines quite passively and, in the opera, “Queen Olympia” is a strong figure, “she herself is the source of power”.

What Flescher aimed to convey in her article was the way the title “Olympia” was understood and perceived during Manet’s time and generally the 1800s France and that it may refer to a “female type”. Could it be that Manet’s Olympia was depicted as a strong example of a female figure although she was a courtesan?

We certainly see a level of confidence in her from her seemingly unwavering gaze and comfort with her nudity.

There are numerous suggestions and postulations about the title “Olympia” and why Manet could have used this title. Some sources also suggest that Manet’s friend Zacharie Astruc may have given the title to Manet’s painting. When Olympia was exhibited at the Salone a part of Astruc’s poem was included for the painting’s catalog entry.

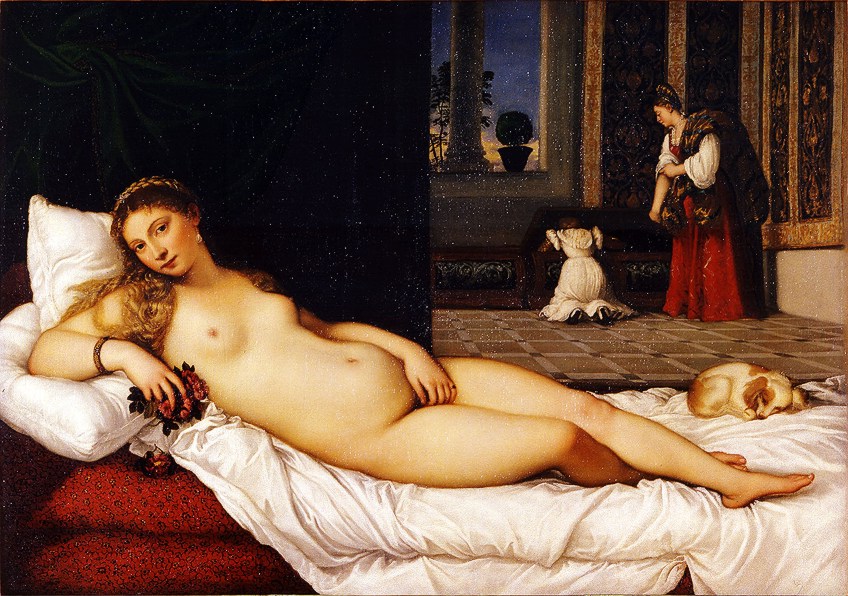

Manet’s Olympia was modeled on the Italian Renaissance Titian and his Venus of Urbino (1534) painting, albeit in his own expressive manner, which would merit an article of its own. We see numerous differences in the way both artists depicted their central female figures; what stood out in Manet’s Olympia was her lack of voluptuousness and thinness, a seeming misrepresentation of how female figures were supposed to be painted, which was voluptuous and delicate as we in Titian’s Venus.

Color and Light

If we look at the color and depiction of light in Manet’s Olympia there is a stark difference to the academic paintings that preceded it. We see a flatter composition because of the way Manet situated the lighter and darker colors. Furthermore, the stark white skin tone of Olympia appears as if there is harsh lighting on her, possibly from a studio light?

Manet included large areas of color, especially the focus on white in the foreground and the background, which is completely darkened. This creates almost no sense of depth in the composition.

Loose Brushstrokes

Manet painted in loose brushstrokes and if we look closely, we will notice how his application of paint appears seemingly haphazard and rushed. This was a newer method of applying paint, especially compared to the academic rules of paint in an almost perfect manner – this caused even more shock in the viewers when the painting was exhibited.

This loose brushwork is a direct reflection of Impressionism and inspired many of the Impressionist artists to follow in Manet’s brushstrokes, so to say. It was a testament to the depiction of modern life and everyday scenes.

Perspective and Line

There is an evident horizontal and vertical play here, for example, the horizontality of Olympia’s figure and her chaise longue taking up the width of the composition. What is notable is the golden vertical line on the wallpaper in the background, dividing the dark red part of the wall from the dark green. This line is spaced only slightly away from Olympia’s genital area where her hand rests.

The fact that Manet barely utilized linear perspective gives the painting a flatter appearance and brings the entire scene closer to us. This painting is often compared to Titian’s “Venus of Urbino” (1534) painting.

We see how Titian created a background scene utilizing linear perspective and a vanishing point in the distance, which gives the scene a sense of depth. Furthermore, the vertical line from the curtain behind Venus directly lines up with her genital area, placing more focus on that area – as noted, this is slightly off-center in Manet’s Olympia.

Scale and Scandal

Manet’s Olympia was painted on a large canvas, measuring 130.5 by 190 centimeters. This was apparently a large format for a Genre painting of the time, as we mentioned earlier about the hierarchy of genres, History Paintings were usually done on large canvases because of their importance.

This is worth noting as we put ourselves in the shoes of academicians in 19th century France: What would they have thought when they viewed such a large, scandalized depiction of what should have been a voluptuous, and maybe meeker, goddess?

Manet’s Olympia: Symbolic References

In Manet’s Olympia, the entire scene might be a symbolic reference, however, there are other elements worth highlighting. In Titian’s Venus of Urbino (1534), we see a sleeping dog near the far-right foot of the chaise longue, this creates a completely different ambiance compared to Manet’s black cat, also situated in the far right of the chaise lounge.

Reportedly, a black cat symbolized promiscuity and female courtesans. Dogs symbolized fidelity and love as we see in Venus of Urbino. Furthermore, dogs were commonly included in Renaissance paintings. This distinction creates further dissonance between Manet’s Olympia and the traditional painting styles.

Manet and Feminism: Olympia, the Maid, and the Matter of a Gaze

Maybe Manet did not expect that his Olympia would cause such an uproar even into the 20th and 21st centuries. It has become a widely debated painting within the Feminism movement, specifically regarding the subject of the male gaze and the role of the maid.

Manet’s maid was a model named Laure who also modeled for him in his other painting titled “Children in the Tuileries Garden” (1862).

Her role in Manet’s Olympia has been critiqued as being a “peripheral” negro and “robot” by the American writer and artist Lorraine O’Grady. In O’Grady’s essay Olympia’s Maid: Reclaiming Black Female Subjectivity (1992) she explores how Manet’s maid is depicted in a western manner and from a European perspective. The maid is seemingly overshadowed by the white woman reclining in front of her.

Furthermore, O’Grady states that the maid is “made to disappear into the background drapery. While the confrontational gaze of Olympia is often referenced as the pinnacle of defiance toward patriarchy, the oppositional gaze of Olympia’s maid is ignored: she is part of the background with little to no attention given to the critical role of her presence”.

Apart from the somewhat dubious role of Manet’s maid, another notion touched on by this painting is the male gaze.

As we mentioned in the above text this painting would have been viewed mostly by men, in the Salon, but it is equally fitting that the subject matter suggests the female is a prostitute who would have been gazed at by men and been the object of their affections and desires.

Manet: Causing a Scene

Manet certainly causes a scene with his modern subject matter placed within a traditional space filled with Classical expectations. This somehow did not stop him from winning a spot in the Salon’s exhibition, even after so many ridiculed and criticized his painting; Manet is widely quoted as stating in a letter to Charles Baudelaire, “They are raining insults upon me!”.

The writer and art historian, Eunice Lipton, has often been quoted as stating about Manet’s images, “robbed as they are of their mythic scaffolding, are bold indeed”. She further explains that Manet’s “women are seen as strong, autonomous beings, firmly saying no to centuries of conventional behavior” and that they are not “updated versions of Venus, Flora, Mary or Salome. Manet’s women are only people”.

Despite Manet disregarding “centuries of conventional behavior” he nonetheless “updated” the idea of how women were portrayed and placed within art and society. Maybe he was regarded as mocking or disrespectful, maybe he was criticized, but he certainly showed the conservative academicians in France what was happening in the real world, on the streets, where real people lived, far removed from the more fantastical and mythical characters from the past.

Take a look at our Olympia by Manet webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is That Famous Painting of a Woman Lying Down?

While there are hundreds of paintings of women lying down, one of the more famous depictions, often criticized as scandalous, is the French Realist and Impressionist Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863). It depicts a woman reclining confidently on a chaise longue starting directly at the viewers. It is believed that Manet depicted this woman as a French prostitute. While she stares at the viewer she is presented with a bouquet of flowers by her maidservant.

What Was the Artist of Olympia Trying to Do?

In Olympia Manet depicts a controversial scene of a reclining prostitute in a pose reminiscent of how goddesses were portrayed in academic paintings from the 19th century. This sparked controversy because Manet highlighted modern life versus the mythological or Biblical scenes that were acceptable according to the art academics of the time. Manet also painted in an expressive manner, which veered away from the stylistic rules of painting that were in line with Classical Antiquity. In Olympia Manet questioned the traditionalism that was so rooted in art and he paved the way for modernism.

Who Was Manet’s Olympia?

The woman in Édouard Manet’s Olympia was a French model, her name was Victorine Meurent; she was also an artist who exhibited at the Salon several times. Meurent also modeled in other paintings by Manet, for example, The Street Singer (1862), Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe (1862 to 1863), Lady with a Parakeet (1866), and The Railway (1873) among others. She also modeled for other artists like the Belgian Realist Alfred Stevens and his painting The Parisian Sphinx (c. 1875 to 1880).

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““Olympia” Manet – An Analysis of Édouard Manet’s Olympia Painting.” Art in Context. November 11, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/olympia-manet/

du Plessis, A. (2021, 11 November). “Olympia” Manet – An Analysis of Édouard Manet’s Olympia Painting. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/olympia-manet/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““Olympia” Manet – An Analysis of Édouard Manet’s Olympia Painting.” Art in Context, November 11, 2021. https://artincontext.org/olympia-manet/.

There are two women in the painting, and it’s disappointing to only research the history of one of them. What’s more, to show a close-up of the cat, the hand, Olympia’s face — and not the black servant. As if she’s not even there.

Her name was Laure.

Olympia’s expression is complex but I see a hardening of her and she is very young – still in her late teens possibly.