Jean Michel Basquiat – Uncovering the Man Behind Basquiat’s Paintings

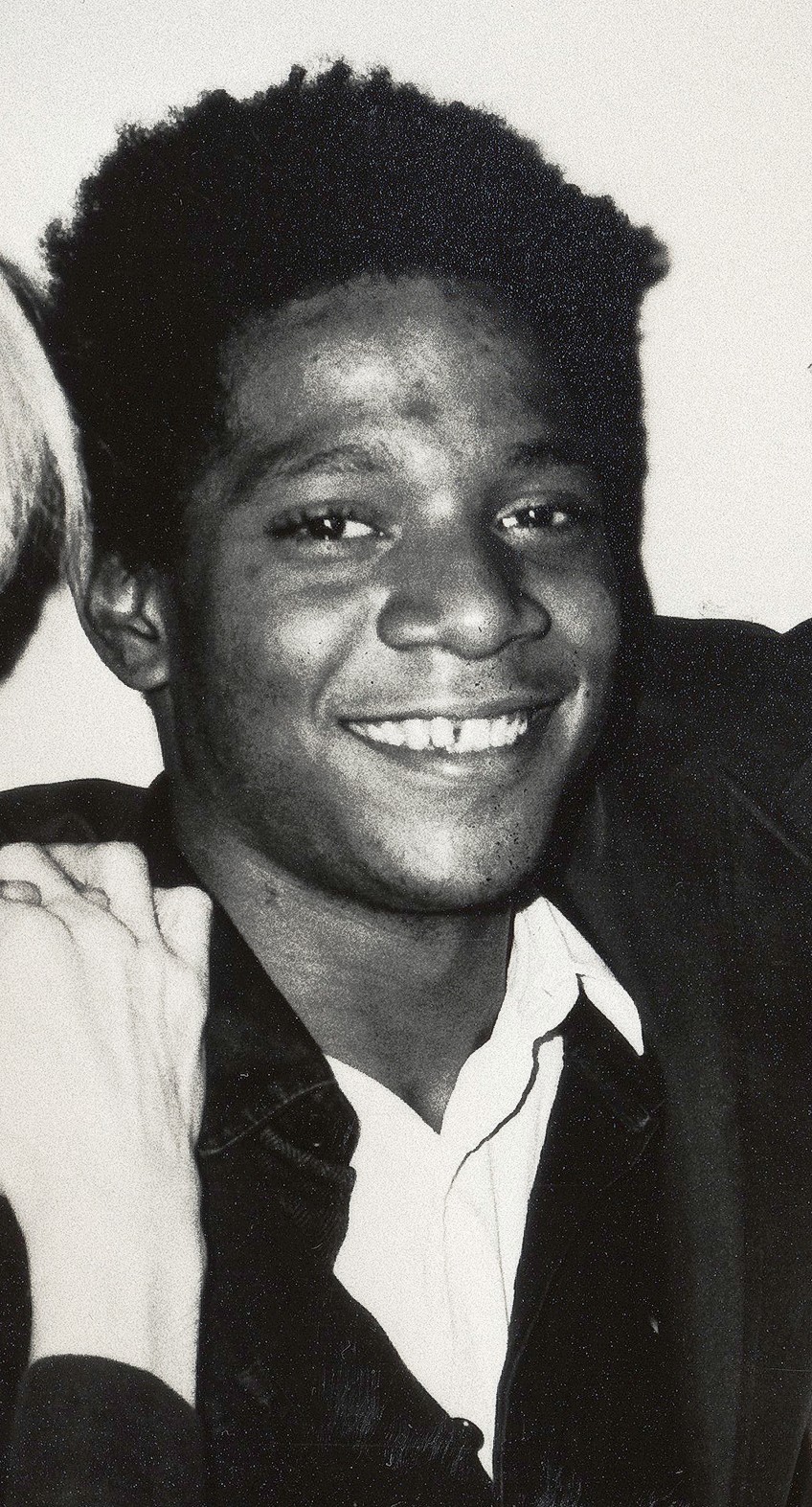

Jean Michel Basquiat always knew that he’d become a famous artist. Even before he became world-famous, he had already been making a name for himself in the New York City art scene. By the early 80s, Basquiat was rubbing shoulders with the likes of Fab Five Freddy, Blondie, Keith Haring, Madonna, and Andy Warhol. In the mostly white art scene of the time, he quickly became a symbolic bridge between high art and popular culture. Even posthumously, he remains a key figure of American pop culture.

The Flashing Spirit of Jean Michel Basquiat

| Date of Birth | December 22, 1960 |

| Date of Death | August 12, 1988 |

| Country of Birth | Brooklyn, New York, USA |

| Associated Art Movements | New-Expressionism, Post Pop |

| Genre / Style | Painting, Graffiti |

| Mediums Used | Oilstick, oil paint, spray paint |

| Dominant Themes | Social commentary, race, African spirituality, pop culture, capitalism |

Self-taught artist Jean Michel Basquiat was not the first Western artist to incorporate African imagery into his practice. However, he was certainly the first to explore the complex set of symbols that constitutes African visual language.

Many of his critics were perplexed by his imagery and his work was often called ‘childlike’ or ‘primitive’. Because of this unfortunate bias, the sophistication of his work is often obscured, while the pertinent references to a rich variety of sources are overlooked.

The Early Years

Basquiat was born in Brooklyn, New York on December 22nd, 1960. Born in the coastal town of Port Au Prince in Haiti, his father Gérard was an accountant. Born in New York, his mother Matilde Andradas was of Puerto Rican descent. Basquiat could speak English, Spanish, and French by the time he was eleven. Jean Michel Basquiat’s biography is culturally rich and would set the tone for his artistic life.

At a young age, his parents divorced and his father remarried. For this reason, and the fact that his mother was committed to a mental institution when he was in his teens, Basquiat’s relationship with his mother was complicated. But Basquiat had always had an interest in art museums and exhibitions. It was his mother who encouraged him. He became a member of the Brooklyn Museum at just six years old after his mother had taken him there for a visit.

In 1968, at the age of eight, when Basquiat was playing on the streets of Brooklyn, he was hit by a car. He was badly injured and admitted to the hospital. During his hospitalization, his mother brought him a copy of Gray’s Anatomy, which is filled with detailed anatomical drawings. The book had such a profound impact on the young Basquiat that he would later name his industrial art noise band Gray. It would also impact his art.

His mother’s influence is something he had a great veneration for and he often referred to her in his paintings. In 1972 his father worked in Puerto Rico so when Basquiat was twelve years old, he and his sister moved there with him, leaving their mother behind though it was her homeland. They lived there based on his work for about a year and a half. But Basquiat’s relationship with his mother would never recover.

The United States has a complex relationship with race. As a child of immigrants growing up in a multicultural household, Basquiat understood the fluidity of identity.

Having moved to the States for a better life, his father preferred to distance himself from the developing country. Rather, he wanted his family to be considered French and showed no interest in sharing his Haitian heritage with his children. Basquiat enjoyed a middle-class upbringing. He was extremely well-read and was exposed to New York’s rich art collections from an early age. He sought inspiration from the masters of Western art who helped him conceive an idea of the painter he wanted to be.

In 1977, Jean Michel Basquiat dropped out of high school a year before he was meant to graduate. His father was so upset, he kicked him out of the house. At 17, he became what we could call a street artist. He trolled the streets of New York tagging public spaces and selling postcards and sweatshirts featuring his art. He lived on cheap red wine and Cheetos. As a result, the artistic persona of a struggling artist emerged.

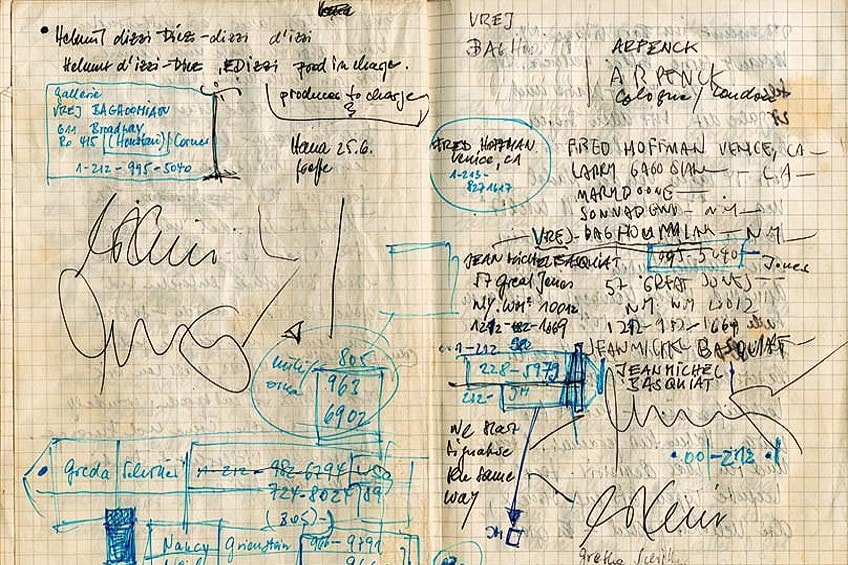

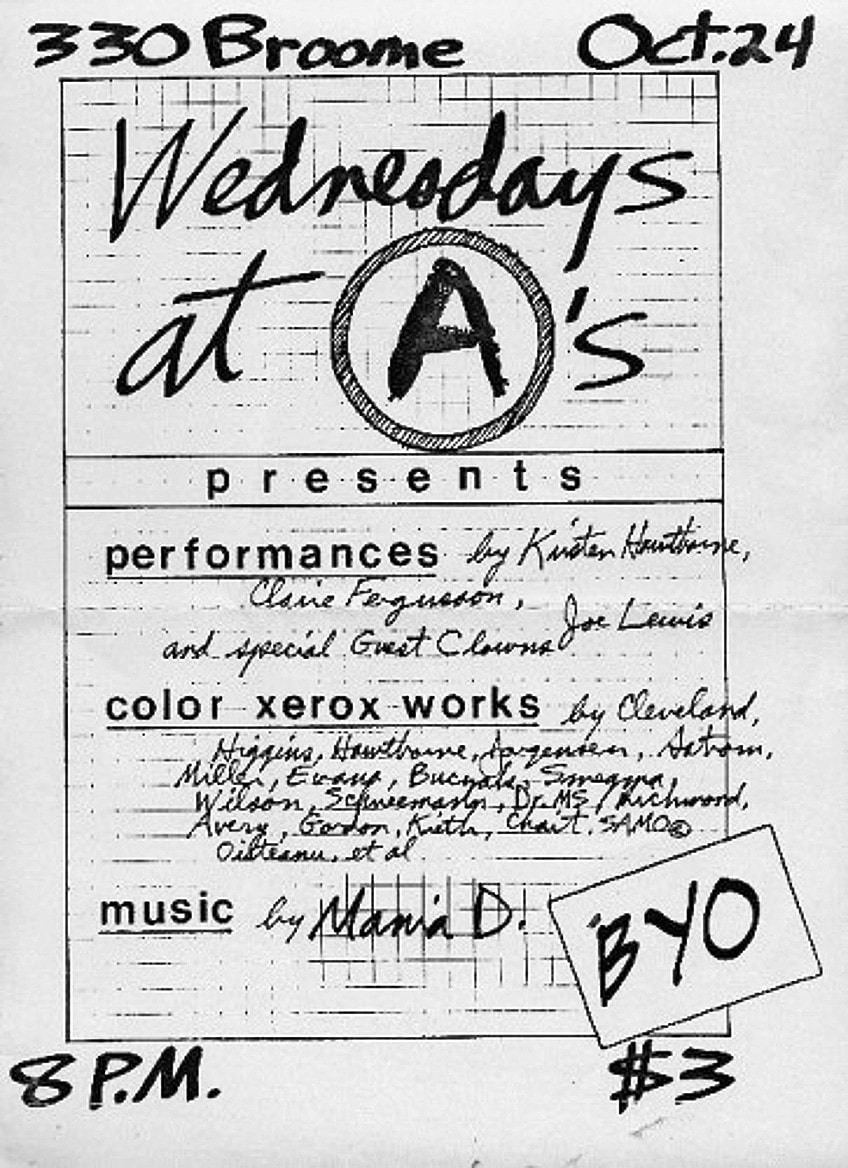

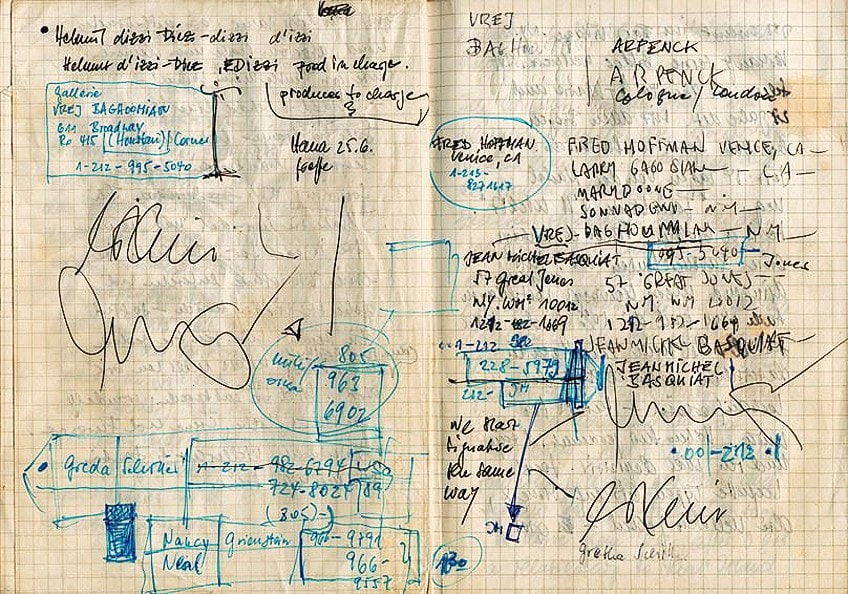

SAMO

In 1977, the same year Jean Michel Basquiat left school, he and his schoolmate Al Diaz started tagging subway trains and buildings throughout Brooklyn and lower Manhattan with phrases signed SAMO. SAMO is an abbreviation for “same old shit” and it was always signed with a copyright symbol. What made it stand out was its cryptic brand of graffiti and copyright symbol and all. It was described as more literary graffiti because it was much more language-focused.

Being a street-level subculture, graffiti tags were like a number or symbol that had more to do with where you lived than your artistic musings. Al Diez and Jean Michel Basquiat made SAMO into a brand that made cheeky, bleak societal commentary that popped up in an unexpected place. Tags like “Popeye Died of Syphilis” were the product of two young men bold enough to make fun of culture.

After three shows it was becoming clear that SAMO was gaining traction, but Basquiat and Diaz had differences about what they wanted for the brand. They had a falling out and in 1980 and the artists signified their disbanding when in 1980, tags declared “SAMO is dead” showed up on buildings around town. But Basquiat assumed SAMO as his own artistic persona, leaving Diaz feeling betrayed, frustrated, and resentful that he seldom got the credit. Even when he was acknowledged, people would often refer to SAMO as “Basquiat and that other guy”.

There is no doubt that Basquiat’s artistic trajectory was influenced by his interest in graffiti, but the graffiti artist image was something of a mirage. He was not necessarily part of the street scene. At the time a graffiti artist accused him of ‘posing’ as one of them. Nonetheless, he quickly gained public attention for his graffiti stylings.

The New York Scene

TV Party was Glenn O’Brien’s public access television show on which Basquiat became a regular guest starting in 1979. Basquiat then SAMO was once introduced as “The most language-oriented of all graffiti artists”. Two years later he starred in Downtown ’81, a film where he played a struggling artist, much like himself.

In 1983, Basquiat produced the rap record called “Beat Bop”, which was a collaboration with Fab Five Freddy, Ramellzee, and K-rod with Al Diaz on percussion.

Many suggest that Basquiat’s art was side-lined for a while. He may have contributed to it with his outsider persona, but he was certainly not an outsider. Jean Michel Basquiat grew up in New York. He had always been drawn to the experimental art and music scene so he frequented all the trendiest places. Over time he came to know influential people and found himself in influential places. People like hip-hop legend Fab Five Freddy, as Basquiat recalled, used to take him to Black Panther meetings. He even had a romantic relationship with Madonna.

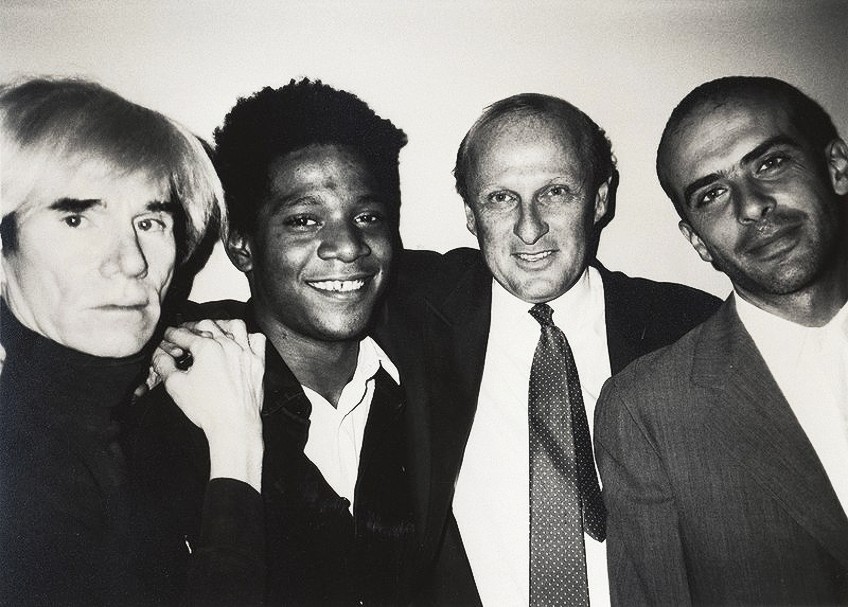

Warhol

Jean Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol are probably art history’s oddest pair. Though the young, ambitious Basquiat had been visiting Andy Warhol’s Factory for years, hoping to make an impact, Warhol paid little attention. Finally, in 1981, they were introduced at Mr. Chow’s, a popular spot in the city.

Two hours after their meeting, Basquiat presented Warhol with Doz Cabezas (1981), a still wet portrait of the both of them. Warhol was in disbelief at how quickly and well it was executed. Their encounter came at a rather interesting time when Basquiat’s star was rising while Warhol’s career had grown stale.

The mutually beneficial dynamic would yield an artistic collaboration spanning from 1983 to 1985. Their collaborations were like conversations across generations and cultural milieus manifested in paint. Some claim that Warhol was in love with Basquiat, others say he was a father figure. Whatever it was, their six-year relationship remains one of the most fruitful endeavors in contemporary art.

Commercial Success

His first exhibition at the DIY Times Square is what burst Basquiat art onto the scene. Hosted in an abandoned massage parlor off 7th Avenue, the exhibition boasted some of the hottest artistic talents of the day including Jenny Holzer, Kenny Scharf, Kiki Smitha, and Keith Haring. In 1980, at the age of 20, Basquiat was invited to present his first solo exhibition in Italy.

In 1981 he produced his first American one-man show at Annina Nosei Gallery who had become his representative. That same year he exhibited in Los Angeles, Rome, Rotterdam, and Zurich. It’s also the year that he became the youngest artist ever to participate in the prestigious international temporary art exhibition Documenta where his paintings were extremely well accepted. His popularity coincided with the emergence of neo-Expressionism.

The 1980s were notoriously permeated by greed and consumer culture. Basquiat’s artistic persona was a conflicted embodiment of that. A lot of the work he was making at the time was about capitalism.

His references to oil companies and corporations and his frequent use of the copyright and trademark symbols indicate a critical engagement with ideas of ownership and exploitation. As he made more and more money, Basquiat began blurring the lines of power.

He spent his money extravagantly, buying expensive suits, and quite literally throwing money out the window, drinking only the finest wines in the most luxurious hotels. Fellow artist and friend Keith Haring once said Basquiat “was all of a sudden becoming the thing he criticized.”

Basquiat, seeing the stereotypes that were imposed on him, set about creating a persona that both satisfied and critiqued the public’s dependence on these limitations. His play on the narrative of the untrained, rough and ready primitive black fuelled the fire of his career. His reality was that he was middle class, art educated, and notoriously ambitious, but he didn’t feel the need to blow his cover if the facade made him rich and famous. He once said: “I’m not a real person. I’m a legend.”

He certainly seemed to have celebrated his commercial success but he also understood that only certain kinds of black artists could be co-opted into the art elite. So, he cultivated a persona where he would feign poverty or perform the primitive. Even after he was making mind-blowing amounts of money, he continued to attend his openings in rags.

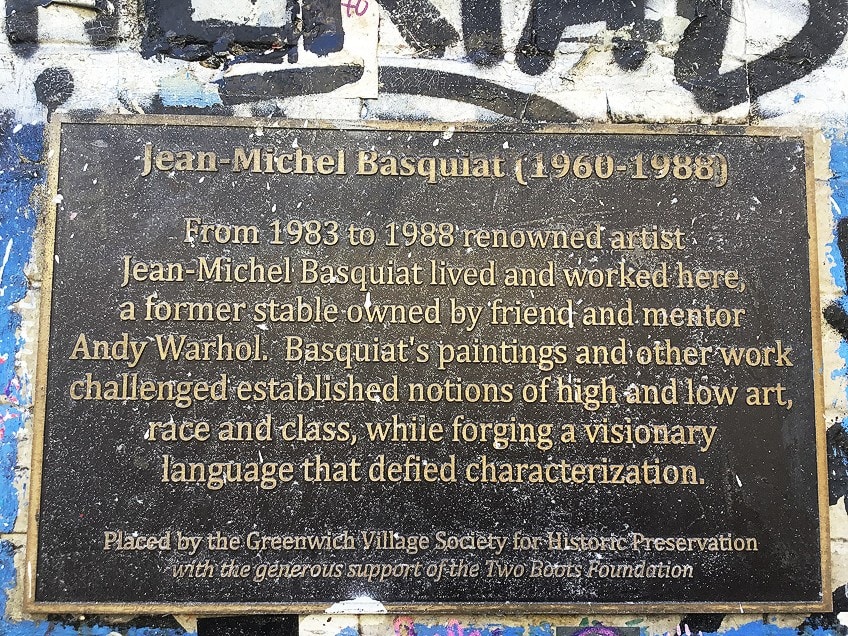

In 1982, for a year Jean Michel Basquiat lived and worked in the basement of Larry Gagauzian’s new home on Market Street in Venice. While the press focussed on the fact that it was a basement, they neglected to mention that it was fifteen hundred feet, four clean white walls, and ten-foot-high ceilings. They also failed to mention that Madonna, his girlfriend at the time, lived there too for a few months. Basquiat once read something that referred to him as “the slave in the basement”, to which he responded: “If I was white, they would call me an artist in residence.”

Basquiat often started work in the early afternoon, working late into the night. His studio was filled with a diverse array of materials and references which he would use to produce his paintings. Even when he wasn’t painting in the studio, it was all a part of the process. There was a mattress on his studio floor, next to it a boombox. Whether it was materials or subject matter, he consumed and regurgitated whatever was around him.

The way Basquiat applied paint was fluid and intuitive. Sometimes he started with abstract passages of paint. Other times he would lead with a drawing, an image, text, or collage. He would lay something down and then destroy most of it leaving only a fraction of the original image.

The paintings on the walls of his studio were in various stages. Some had only a few marks while others had been labored over with multiple layers. In spite of this process, Basquiat worked at a fast pace. Always moving between his canvases, working and reworking.

Art and Meaning

Much of Jean Michel Basquiat’s frustration with his artistic persona was rooted in a sense of alienation in the 1980s art world. While he had a wildly successful commercial career, he was often regarded as a wunderkind because of his exotically “childish” technique.

The true consequences of this unfounded primitivization will never be fathomed, but more can be done to scrutinize his conceptual foundations in order to afford this erudite artist the kind of credit he seemed to be after.

Language, Text, and Context

As he was multilingual, he was interested in the concept of language. Particularly its use as a way of slipping between communities. His focus was on the ability of language to permeate a variety of meanings and relate to diverse audiences. He would often use particular words in Spanish, French, or Creole as a way of dropping hints to very specific audiences.

In his work The History of Black People (1983) we see a large black ship across the center of the canvas and two blocks along the side. There is a vignette on the right where Basquiat had inscribed the word Memphis in a box. Above it, the word “Thebes” and below it is “Tennessee”, referring to Memphis of Ancient Egypt. Basquiat was showing his linguistic capacity to signify Egypt and the Americas, and perhaps the transition between the two.

While it was clear that he was a wordsmith who cared about language and meaning, he also used words as images. He would often employ a visual technique for linguistic purposes. For example, he would draw a face and instead of drawing the teeth, he would write the word teeth, or draw a figure and write feet where we would expect the feet to be.

In Undiscovered Genius of The Mississippi Delta (1983) see another example of him using words as imagery. Basquiat wrote, crossed out, and repeated words to create rhythm. He talked about the crossing out of words as a means of making people want to read them more. But he also used repetition as a way of disempowering certain words.

In the painting, Mark Twain’s name is repeated. An author whose book Adventures of Huckleberry Finn followed a protagonist across the Mississippi River. It is set twenty years after the abolition of slavery and is a scathing satire of the attitudes towards racism in America. The repetition of the words “Mississippi” and “Negroes” is Basquiat’s way of hammering out the traumatic national history of slavery and racism in the United States. The words are emptied of authority and meaning.

A lot of the works are untitled, so the names they go by are given these because of the words that Basquiat wrote on them. One has to wonder whether that was part of his plan. Basquiat’s work asks us to be complicit in the interpretation and meaning-making process. The artist creates a dialogue with us, leaving enough mystery for the viewer to be able to interpret his images in so many ways.

Equals Pi (1982) like most of Basquiat’s work can seem chaotic to the untrained eye. In what looks like a blackboard on which Basquiat scribbles his equations, this painting is based on the dimensions of a cone. “Knowledge of the Cone” are the words written at the top of the painting to alert us as to what the equation means. The cone has many implications, but importantly cones give us the ability to see color. Color is basically refracted light. He awakens us to consider cones in their various dimensions and perception is key. Light is information. Information is awareness.

The Black Experience

There is little evidence to suggest Basquiat had any relationship with other African American visual artists. While they had not come close to the level of success, he had experienced artists like Romare Barden and David Hammons were living and working during his lifetime. Nor does he seem to have made many references to the Harlem Renaissance, a New York-based art movement that occurred in the 1920s.

However, Jean Michel Basquiat was plagued by the prejudice he saw being pitched against black men. Even as he rose to fame, he was still facing racism on a daily basis including in the art community. He once recounted exiting the opening night of a successful exhibition and realizing that no cab would stop for him.

When he spoke out about his experiences of racism in the art world, his own friend Julien Schnabel called him fragile. By saying this Schnabel implied that the issue was with Basquiat and not the racist art world. In spite of this Julien Schnabel was given the reins to direct the 1996 Basquiat biopic, which starred Jeffrey Wright as Basquiat and David Bowie as Warhol.

The art world labeled Basquiat as a childlike figure in western art, it is white artists that he cited the most. His extensive knowledge of art, linguistics, and music, shows that he deserved more credit. Because he looked up to artists like Leonardo Da Vinci, Manet, Pablo Picasso, Willem De Kooning, and Jackson Pollock, even those who recognized his talent would often credit his brilliance to his white predecessors. During his lifetime, the press had gone as far as labeling him the ‘Black Picasso’. He reported feeling insulted by this term.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YE3wxioYluc

He explored the way he saw himself and the way others saw him in his work. But his definitions of himself remain unclear. He felt that society would not allow him the complexity of identity one way or the other, so he chose ambiguity. He may have been identified as an immigrant. However, he also saw himself as a product of the African diaspora. He had a particular interest in how cultures in the new world retained their Africanness.

Basquiat’s paintings used African and African American symbology and icons to represent a concept of heroism. Exclusively, his heroic figures were black male musicians or athletes. This was either a depiction of how he saw heroism or a critique of heroism. In an interview, he once said that the reason he put black male figures into his paintings was that he felt they experienced a level of erasure.

Per Capita (1981), like a lot of his work, has a number of boxing references. It was based on the political and sports figure Mohammed Ali was referenced in Basquiat’s work under his government name Cassius Clay. In this painting, we can see Basquiat explore the concept of the empowered black man. Basquiat referred to a number of other black boxers in his work like Jack Johnson, and Sugar Ray Robinson.

But his portrayals were not always affirmative. In Irony of Negro Plcemn (1981) Basquiat addresses the oppressed subject wearing the oppressor’s uniform. La Hara (1981) is an old-fashioned Puerto Rican term for “police”. It comes from the surname O’Hara which was common in the predominantly Irish police force of the 1940s and 1950s New York. On this rare occasion, Basquiat ventured to depict white men.

In Defacement (1983) Basquiat responded to Michael Stewart’s death. Stewart was a fellow aspiring artist and had been caught tagging the New York subway on September 15, 1983. The details of what happened then are unclear, but we know that as a result of his arrest Stewart spent thirteen days in a coma and died from his injuries on the 28th of September 1983. Basquiat was not a close friend of Stewart’s but this instance of police brutality clearly hit too close for comfort. He was heard saying “it could have been me”.

Black folk would remain the subjects of his paintings because he wanted to offer a more realistic and regular portrayal of black people in modern art.

He paved the way for black artists who want to interrogate race or racial history in their work and even those who preferred not to deal with race at all. He wanted his work to illuminate the rich diversity of their cultural experience. Through his paintings, he expressed his love of self and humanity as told through the experience of being a black man.

The Head

The human head is a common feature of Basquiat’s work. Gray’s anatomy would remain a constant influence and he continued to quote Leonardo Da Vinci whose annotated manuscripts Basquiat owned. Basquiat’s depiction of the human head is neither realistic nor grossly distorted. He used the conceptual idea of the human head to portray a recognition of self. This stroke of symbolism connected him to expressionism which had occurred some decades earlier.

Basquiat’s head figures were also influenced by African masks with the skull figures representing death, while conversely engaging lively African ancestral beliefs bolstered by vibrant colors. These two influences perhaps depicted multiple facets of Basquiat himself.

Between 1981 and 1983, Basquiat produced many of his most compelling paintings which focussed on the human head. Some paintings feature a single head, others a group. Two Heads on Gold (1982) and Mitchell Crew (1983) are examples where he shows a number of head studies on one canvas.

One of the most important of the head paintings is Philistines (1982). The central figure had exposed bones. One of the head figures is rendered simply as head and neck. Its eyes bulge out of the sockets. The open mouths baring teeth appear abnormally big. In early 1981, Basquiat produced a painting of another huge head. Untitled (1981) is one of the most compelling of the conceptually driven head paintings and it marked Basquiat’s as a new icon in the canon of 20th-century art.

Back of the Neck (1983) shows his pictorial strategy Basquiat had begun to explore in early 1981 and one of the most intense forays into the work of Pablo Picasso and sub-Saharan African sculpture which separates it from the other head images produced during his time. He’s interested in the simultaneous experience of both external and internal realms. While the heads have the expected features of eyes, nose, and mouth, it also presents us with depictions of an interior dimension.

“Untitled, Head” (1982) which was sold for an unfathomable amount of money, has been eclipsed by its history-making price. The main subject of this work is a large bravado head, which, executed with bold brushwork and color, is considered to be a form of self-portraiture. This seminal work shows the eyes and mouth as a passageway into the hidden realm of inner life.

In these paintings, Basquiat’s fascination with human anatomy coincided with his deep curiosity for aspects of a psychological dimension, creating a new way of seeing subjectivity. In November 1990, Basquiat would present no less than 27 head studies at his seminal drawing exhibition at the Howard Miller Gallery in New York City.

The Crown

Basquiat’s symbolism includes ladders, crosses, and arrows, but by far the symbol that is most recognizable was the crown. The crown is ubiquitous and quite significant in Basquiat’s work. He used it in his paintings, notebooks, and sculptures.

At times, Basquiat would simply sign his work with a crown. He finds inspiration for the crown in African legend, attempting to refer to African royalty in a contemporary style. The crown was part of graffiti street lore and represented power and nobility.

Symbols reserved for the greatest masters and legends of graffiti. Of the various array of symbols in African and graffiti art, Jean Michel Basquiat responded to the crown. The three points on top of the crown became part of Basquiat’s iconography.

Basquiat often referred to the concept of dual realities. In black studies, this is called double consciousness. Basquiat uses the crown to offer his black subjects an alternative realm in which they too can be kings.

This idea of black folk as self-proclaimed kings was a vital part of black affirmative culture following the Civil Right Movement of the 1950s and 60s. Mohammed Ali, who emerged onto the scene around that time, called himself “The King of The World”.

Flesh and Spirit

As he was an avid reader, Basquiat had an interest in both the visual and the musical arts, he got himself a copy of Robert Farris Thompson’s book Flash of the Spirit as soon as it was released. Flash of The Spirit is a roughly 300-page book on African and Afro-American Art and philosophy originally published in 1983.

It was Robert Farris Thompson’s most popular book and made a huge impact on young Basquiat. He once said that Robert Farris Thompson was the only person who would truly understand his art.

The broadly scoped book studies five various cultures and their artistic and spiritual practices. The first was the Yoruba from Nigeria. Thompson explored how the different designs in their artifacts are rooted in the Ifa religion. The second introduced the Congo people of Zaïre. Their art is observed through drawings called cosmograms which depict religious concepts. The author considered how medicinal charms often had an artistic element in their construction.

The following chapter looked at Vodou in Haiti. Along with his analysis of paintings and sculptures, the author also looks at linguistics and shows the linkages between Voodoo/Vodun practices in Haiti, and the Yoruba and Dahomean cultures of Africa. He surveys how certain customs have survived into the diaspora. The fourth chapter explores art from Mali and the final chapter, art from Cameroon.

Having engaged with direct sources including voodoo practitioners, Ifa diviners and also visited various locations where the art was located in Africa and the Caribbean, the book offers not only art history but broader information about the various societies. Farris Thompson demonstrated a deep respect for African culture in his assessment of the artistic traditions on their own terms and within their cultural context.

Jean Michel Basquiat’s painting, “Flesh and Spirit” (1982 – 1983) is an homage to “Flash of the Spirit”. The colossal four-panel painting is one of the largest Basquiat ever made and was completed in 1983.

Basquiat echoed the cosmogram using two horizontal panels linked to create four quadrants. The cosmogram is a symbol of the human connection to the ancestral realm and the arrows point to the interplay between them. In Flesh and Spirit, Basquiat is paying homage to the cultural and aesthetic influences that inform his practice. He adorns his contemporary images with Africana religious traditional icons as outlined in Thompson’s book. This work declares Basquiat’s maturity as an artist and his ability to send discerning messages to those who know and care to receive them.

Bebop and Hip Hop

Music has always played an important part in Jean Michel Basquiat’s process. While working in the studio, he had to have the television on or some kind of noise in the background. His earliest sonic experiments were focused on rock and noise music, and he was briefly in an experimental noise band called Gray.

In the 1980s, as he became more prominent in the New York creative scene, his tastes developed. He experienced Caribbean music, African music, and the relatively new cultural phenomenon of hip-hop music.

Hip hop has four formal elements which are emceeing, DJing, breakdancing, and graffiti. Basquiat dabbled in at least two of these. Graffiti and taggers are of course a foundational element of hip hop culture and they would influence Basquiat to become SAMO. He created the cover art for the Beat Bop record which had sonic references to the band Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five and is directly influenced by hip hop freestyling cultures. He played a club DJ in Blondie’s Rapture music video.

Horn Players (1983) depicts iconic musicians sax player Charlie Parker and horn player Dizzy Gillespie. Basquiat has rendered both these musicians in visual and linguistic portraits. Charlie Parker’s saxophone emits pink musical notes on the left of the canvas. In drawing a straight line between bebop and hip hop, Basquiat cast himself as the illuminator of the connection between these two worlds. He evoked the trajectory between bebop’s emergence in the post-war 1930s and the emergence of hip hop at the beginning of the late 1970s.

As in Robert Farris Thompson’s Flash of the Spirit, music is not perceived as only a part of black culture, but a tool for understanding it. The trajectory of black sonic traditions across the globe and across time resonated with Basquiat. His paintings would increasingly demonstrate his connection to bebop and hip hop. Overlapping the various traditions of hybridity and mixing of unlikely elements from the past and the present in order to speak to what it meant to be an American at the time.

The crown shows up in jazz symbology with legends like Duke Ellington and Count Bassey choosing names that indicated nobility. The symbol is as ubiquitous in hip hop with legends like Notorious BIG having dubbed himself the King Of New York.

In his painting, “Charles the First” (1982), which once again referenced Charlie Parker, we see a text “Most Young Kings Get Their Heads Cut Off”. This is a reference of course to the classic Shakespeare quote: “uneasy is the head that wears the crown”. The cutting off of heads could be a reference to police brutality and the myriad of other issues faced by black people in a problematic society.

Bebop musicians were serious about their artistry and wanted to be regarded at the same level as classical musicians. They rejected the notion of music as mere entertainment. In a painting like Obnoxious Liberals (1982) Basquiat alerts us that he similarly had a desire to be taken seriously as an artist. The inscription “Not For Sale” is perhaps a response to reports that rich patrons of Basquiat’s early paintings were requesting to have made to order art, so as to better match their furniture.

Basquiat’s practice of crossing out words can be compared to the deconstructive nature of jazz and bebop music. Jazz musicians deconstructed the American songbook so that they could emphasize the creative role of the musician. Hip hop DJs and producers scratch and remix existing records in order to find a new sound. When Basquiat used the practice of scratching, crossing out words it was a visual manifestation of these black sonic traditions.

What many people call chaotic work, Basquiat would probably call improvisation. Improvisation is the height of transcendence in jazz music.

Serious musicians were expected to draw on a variety of sources to create their art. In hip hop, the futuristic soundscapes created by DJs and producers could also be classified as chaotic as they constituted the destruction of something else. The objective is to make a unique original statement, which is what Basquiat attempted. He knew instinctively that painting with no formula would trigger new revelations.

Paintings like Irony of A Negro Policeman (1981) seem both historical and contemporary at the same time. Police brutality is a long-standing issue for black people across the globe. All the time songs and images are being made about people like Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Trevon Martin, or George Floyd – black people who died based on an encounter with the police. One of the most iconic sonic iterations of this global frustration is NWAs infamous song F*** The Police.

Jean Michel Basquiat’s Death

Riding with Death (1988) was the last painting Basquiat ever made. Death had always been a part of Basquiat’s work. What is haunting about this painting is the economy of means and the prophetic ghostliness. There is normally so much information on a Basquiat surface that one can hardly take it all in.

Here he strips it all the way back to its bare bones. Scholars generally agree that the skeleton riding figure is Basquiat himself. The color palette has an odd, anxious sickliness to it. Towards the end of his life, Basquiat felt isolated by his level of success. This was the catalyst for his development of heroin addiction.

He had become a celebrity and he had plenty of money, but all he wanted was to be taken seriously by the art establishment. Though the commercial had embraced him, museums were lagging. From the early stages of his career, he knew he wanted to be a star and make money. For a black man to claim he’d become one of the greatest painters in 1979 was a revolutionary statement.

Towards the end of his life, he had so much money that he didn’t know what to do with it. He was making a lot of money, but he had not garnered critical acclaim from the art elite. He had had incredible success but received little critical attention and was only written about in exhibition catalogs.

Because museums didn’t take him as seriously as the art market did, and the quick absorption into the art market that’s still happening, he’s still setting records. All of the work got absorbed into private collections and is not available for scholars.

His work was rejected by the MoMa and the Whitney, which frustrated him. He still felt like an outsider, and he was still openly disregarded as a primitive savant. In 1988, he left New York for Hawaii in an attempt to get sober. He returned to his Great Jones Street art studio in New York and died tragically of an accidental overdose on the 12th of August 1988.

Jean Michel Basquiat’s career lasted only eight years and he died at 27 years old.

A Lasting Legacy

He might have died young, but famous Basquiat paintings continue his legacy. Jean Michel Basquiat’s biography will intrigue generations to come. He was a multi-faceted artist who practiced many art forms throughout his career. The lyrical abstraction is influenced by jazz, hip hop, African, American, and Western art culture.

The diagrammatic way in which Basquiat worked indicated that he was attempting to organize and process information.

Even in the white art world where he was still regarded with suspicion and mistrust, he dared to produce paintings that engaged in social critique. Basquiat’s emergence preceded the breakthrough 1993 Whitney Biennale where many African American and Latino artists got recognition through this large-scale exhibition. The exhibition itself was criticized by the press for being “overly political” and “overly ethnic”.

While these artists could band together and demonstrate their collective need for representation and respect, Basquiat truly stood alone in the hostile milieu of the western art world at that historical moment. His struggles resonate with young people who face a similar hostility at the same or similar institutions today. But thanks to his irreplaceable contributions, there has been considerable progress. He may not be able to see it, but today his art is housed at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which had once rejected him, the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, and other prestigious art institutions. Thanks to his self-belief and prolific output of paintings, his work would see his dream come true.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Owns the Basquiat Estate?

The $10 million Jean Michel Basquiat estate is managed by his sisters, Lisane Basquiat and Jeanine Heriveaux.

How Much Is Jean Michel Basquiat’s Work?

Basquiat paintings break records when it comes to their sale price. Undiscovered Genius of the Mississippi Delta (1983) sold for $23.7 million in May 2014. That was nothing compared to one of the most famous Basquiat paintings Untitled, Head (1982) which sold for $110.5 million, to the Japanese mega art collector Yusaku Maezawa on May 18, 2017. Another Untitled Head (1983) was sold for $15.2 million in June 2020. All of these were sold at Sotheby’s.

Do Beyonce and Jay-Z Own One of the Basquiat Paintings?

We know that Jay-Z bought Mecca (1982) in 2013 at Sotheby’s for $4.2 million. However, because of Basquiat’s commercial success, a lot of his work is hidden in the private collections of the rich. Up until recently, Equals Pi (1982) was once a never-before-seen work. That is until it was recently purchased by Tiffany’s Co, who featured in an ad campaign alongside Jay-Z and Beyonce.

How Did Jean Michel Basquiat Die?

Jean Michel Basquiat’s death was caused by a heroin overdose. Many people claim that it was accidental. Basquiat had been dealing with drug use problems for a while before he was found dead in his apartment.

Why Did Madonna and Jean Michel Basquiat Break Up?

During an appearance on the Howard Stern Show, Madonna opened up about her relationship with Basquiat, saying that she left him because he wouldn’t stop doing heroin. The breakup was pretty ugly, with Basquiat taking back the paintings he’d made for her and painting over them.

Did Basquiat’s Friends Try to Sell His Art After He Died?

When his ex-girlfriend Alexis Adler tried to sell her 50-piece collection of what she claimed were Basquiat works to the auction house Christie’s, Basquiat’s family called them fakes. They promptly slapped her with a $1 million lawsuit.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Jean Michel Basquiat – Uncovering the Man Behind Basquiat’s Paintings.” Art in Context. March 23, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/jean-michel-basquiat/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 23 March). Jean Michel Basquiat – Uncovering the Man Behind Basquiat’s Paintings. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/jean-michel-basquiat/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Jean Michel Basquiat – Uncovering the Man Behind Basquiat’s Paintings.” Art in Context, March 23, 2022. https://artincontext.org/jean-michel-basquiat/.