Alberto Giacometti – Modernist Master of Elongated Form

Alberto Giacometti’s amazing oeuvre tracks the evolving passions of art in Europe both before and following World War II. Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures in the 1930s exhibited Surrealist and creative sculptural shapes, sometimes suggestive of games and toys. After the war, as an Existentialist, Giacometti’s paintings paved the way for a form that encapsulated the philosophy’s concerns in observation, isolation, and dread. Although he paints and draws, the Swiss-born artist is most known for his sculptures, such as Giacometti’s Walking Man, one of his most expensive statues.

Alberto Giacometti’s Biography

| Nationality | Swiss |

| Date of Birth | 10 October 1901 |

| Date of Death | 11 January 1966 |

| Place of Birth | Stampa, Switzerland |

Giacometti is most known for his figurative works, which contributed to popularizing the subject of the tortured human figure as a representation of post-war anguish. Giacometti’s work from the 1930s is often regarded as the most significant contributor to Surrealist sculpture. He created a range of sculptural objects to investigate Freudian psychoanalytic topics like sexuality, desire, and trauma.

Some were inspired by primitive artwork, but those that mimic toys, games, and architectural models were possibly the most remarkable. They nearly want the observer to physically engage with them, which was a novel concept at the time.

Childhood and Early Training

Alberto Giacometti was born in the eastern Swiss alpine village of Borgonovo in 1901. He was the eldest of four siblings born to post-Impressionist artist Giovanni Giacometti and his wife Annetta Giacometti-Stampa, whose family were wealthy landowners in the region. In addition to his father, numerous relatives of Giacometti’s wider family were painters, notably Symbolist artist Augusto Giacometti and Fauvist Cuno Amiet, godfather to Alberto.

When Giacometti was just 11 years old, he started sending pencil and crayon sketches to his godfather Amiet, the majority of which he kept and are still preserved today.

In the years thereafter, he has experimented with oils and still lifes, frequently using his relatives as models. At the age of 12, he completed his first artwork. Giacometti studied at the Evangelical School in Schiers in 1915, where he proceeded to paint in a tiny private workshop.

Afterward, he attended Geneva’s École des Arts Industriels, where he pursued painting, sketching, and sculpture with sculptor Maurice Sarkissoff and Pointillist artist David Estoppey. Giacometti flew to Italy with his father in May 1920, when he saw Giotto’s paintings in Padua, Jacopo Tintoretto’s artworks at the Venice Biennale, and the art of ancient Egypt at the Archeological Museum in Florence. Soon after, he relocated to Paris, where he participated in various painting programs and became interested in Cubism and primitive arts.

“The Spoon Woman” (1927), his first significant bronze sculpture piece, was shown at the Salon des Tuileries in 1926.

Mature Period

Giacometti was warmly accepted into Surrealist circles during the 1930s, and he grew close to individuals like Joan Miró, Man Ray, and Max Ernst, as well as the movement’s founders, Louis Aragon and André Breton. However, he also published material in Documents, a monthly published by writer Georges Bataille, who was at the time promoting an alternative version of Surrealism to Breton’s.

Critics today feel that Bataille’s theories influenced some of Giacometti’s sculptures, including “Suspended Ball” (1931).

Giacometti and Diego, his brother, escaped Paris by bicycle in June 1940, narrowly avoiding a confrontation with the advancing German Wehrmacht (they observed the city’s devastation from afar the next day). During this time, Giacometti stayed in France and formed contacts with Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre, intellectuals who would later inspire his figurative works.

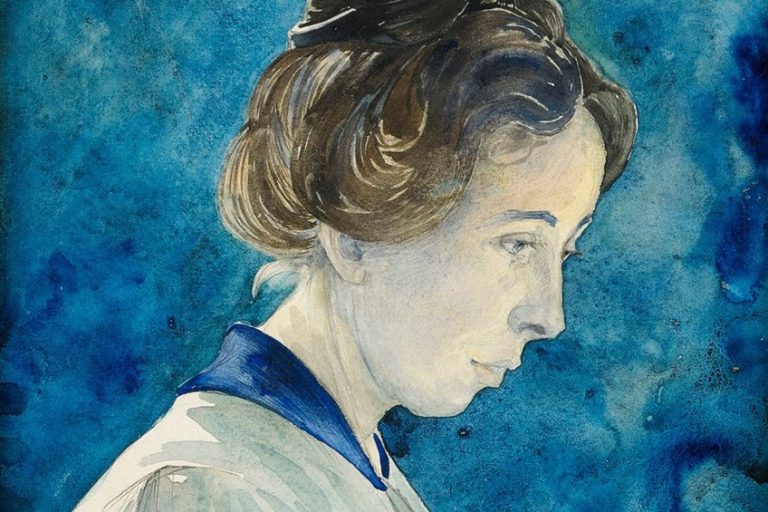

Following the emancipation of Paris and his three-year sabbatical in Geneva, Giacometti reappeared in the French city in 1946. Annette Arm, his old lover, rejoined him that same year, and the two wedded in 1949. Arm posed for him multiple times, including in the oil painting Annette with Chariot (1950).

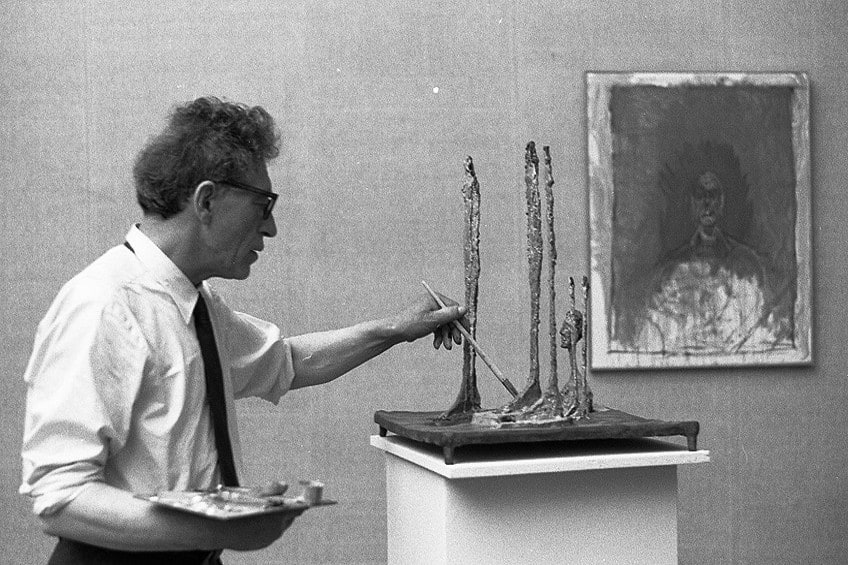

Giacometti developed his mature manner of extended figures while residing in Paris throughout these years, reputedly after spending time drawing passers-by in the city streets.

Late Period and Death

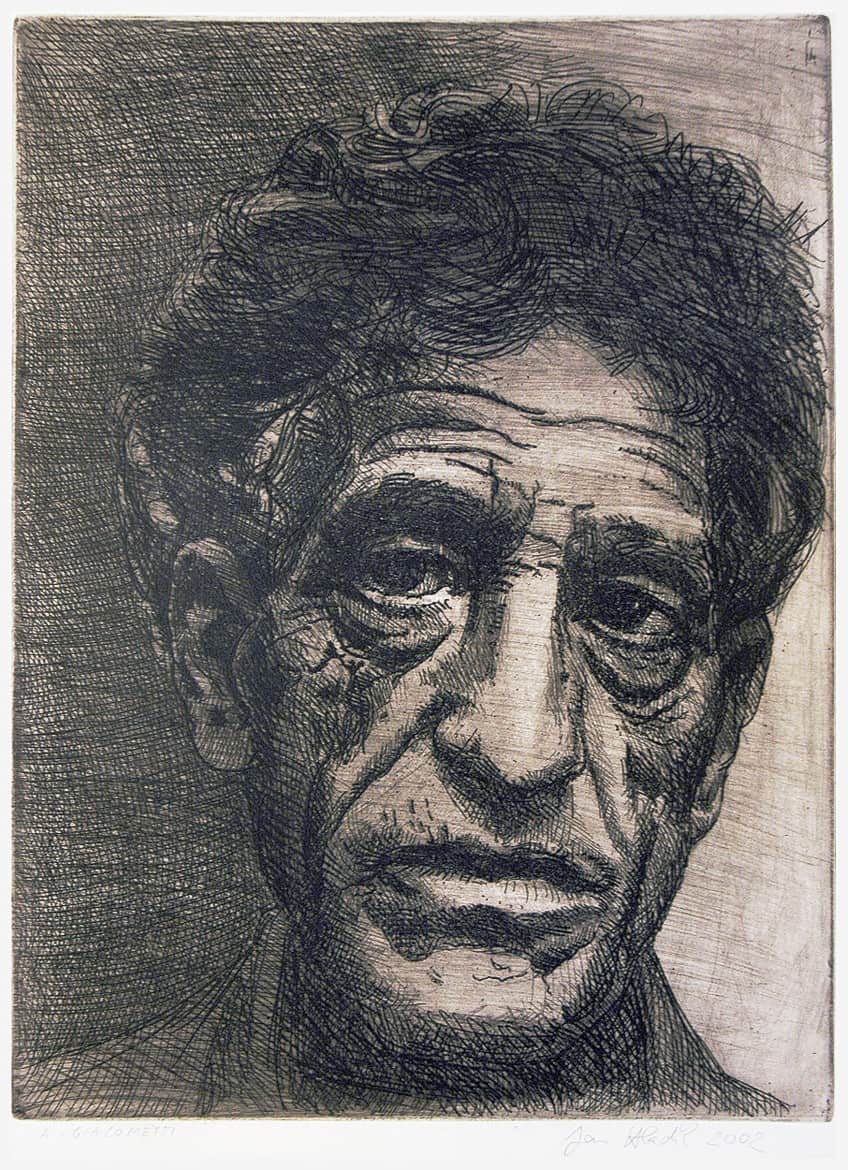

As Giacometti’s technique matured during the 1950s and 1960s, his bronze figures got bigger and more intricate, ranging from Woman of Venice II (1956), which stood about four feet tall, to Tall Woman II (1960), which was over nine feet tall. He also focused more on portraiture, both paintings and sculpting. Diego and Annette were among his frequent models, as was Isaku Yanaihara, a Japanese senior lecturer and author whom he met in 1955.

Giacometti was worldwide renowned by the 1960s, but his health deteriorated.

He suffered from cardiac and circulation issues. Nonetheless, he persisted to create, and in his dying weeks, he was engaged with a bust and artwork of Elie Lotar, a close personal friend and French photographer.

Annette Giacometti had become the sole custodian of his intellectual property because he had no children.

She labored to compile a comprehensive inventory of her late husband’s legitimate works, as well as gather data on the location and manufacturing of his works and battle the expanding number of falsified creations. When she died in 1993, the French government established the Fondation Giacometti. Roland Dumas was convicted in May 2007 of unlawfully selling Giacometti’s paintings to a prominent auctioneer.

Artistic Analysis

Both pivotal periods in Giacometti’s career produced breakthroughs that impacted a wide spectrum of artists. The Surrealist quality of Giacometti’s sculptures from the 1930s, for example, impacted Henry Moore, creating the Surrealism that would be such an essential element of Moore’s work throughout his life. Moore’s own inventive attempts in the 1930s would be difficult to envisage without Giacometti’s model.

And, at a time when abstract art ruled, Giacometti’s representational work was critical in re-establishing the form as a viable theme in the postwar period.

Legacy and Accomplishments

His slender bronze figures, which look pierced and frail, crushed in space, are visual representations of Existentialist ideas, markers of modern humanity’s shattered state. Giacometti eschewed Surrealism and abstraction in the late 1930s, becoming increasingly focused on how to express the human form in a compelling illusion of actual space.

He wished to show figures in such a way that a real feeling of spatial distance could be captured, so that we, as spectators, might participate in the artist’s own sensation of distance from his subject, or from the meeting that inspired the piece.

He came up with a method that included reducing the figures to the smallest possible proportions. Many authors engaged in Existentialism were intrigued by Giacometti’s postwar success – establishing a vocabulary through which to describe the figure in actual space. Both of these ideologies have concepts about self-consciousness and how we interact with other people, and Giacometti’s work was regarded to effectively portray the tone of melancholy, isolation, and solitude that these beliefs implied.

Even though art form swept the art world in both Europe and the United States in the 1950s, Giacometti’s figurative sculpture became a profoundly important paradigm of how the human form may return to art.

His figures depicted people who were alone in the world, bent inward, and unable to engage with their peers despite a strong desire to do so.

Art Style Analysis

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Giacometti’s sculptural method was: “Three Men Walking (II), 1949, typifies his style with its rough, worn, intensively wrought surfaces. These figures, stripped down to their bare essentials, recall lone trees in winter with no leaves. Giacometti seldom deviated from the three subjects that interested him—the strolling man, the standing, naked lady, and the bust—or all three, mixed in various groupings—within this style.”

“Figures were never a dense bulk, but like a translucent architecture,” Giacometti stated in a letter to Pierre Matisse.

Alberto Giacometti writes in the letter about how nostalgic he was for the realism, and classical busts of his boyhood, and describes the narrative of the existential dilemma that led to the style he became known for. “I rekindled my desire to create figure-based compositions. For this, I needed to make (quickly, I reasoned; in passing) one or two drawings from nature, only enough to grasp the design of a head, of a full figure, and I took a model in 1935. This research should take two weeks, I reasoned, and then I’d be able to finish my compositions.

From 1935 through 1940, I spent every day with the model. Nothing went as planned. For me, a head became a wholly unfamiliar and dimensionless entity”. Alberto Giacometti’s difficulties in re-approaching the form as an adult is often viewed as an indication of the existential battle for meaning, rather than a technical shortcoming because he attained exquisite realism with ease while he was creating busts in his early teens.

Although Giacometti was a crucial figure in the Surrealist movement, his work defies classification.

Several call it formalist, while others say it’s expressionist or has anything to do with Deleuze’s “blocs of feeling.” Even after his expulsion from the Surrealist group, his sculptures were a reflection of his emotional reaction to the topic, even though the objective was typically mimicry. He sought to make renderings of his models as he saw them and as he believed they should be seen.

He once stated that he was sculpting “the shadow that is cast,” rather than the human form.

The attenuated shapes of Giacometti’s figures, according to scholar William Barrett, represent the perspective of 20th-century existentialism that modern existence is becoming increasingly hollow and devoid of significance. “All of today’s sculptures, like those of the past, will be shattered at some point. As a result, it’s critical to meticulously craft one’s work down to the tiniest detail and infuse life into every atom of substance.”

Famous Examples of Giacometti’s Paintings and Sculptures

Alberto Giacometti is most renowned for his bronze sculptures of tall, slender human figures created between 1945 and 1960, including Giacometti’s Walking Man, one of his most expensive statues. The impressions he got from people scurrying in the huge metropolis impacted Alberto Giacometti’s work. “A sequence of moments of stillness,” he described people in motion. The emaciated figures are frequently understood as symbols of mankind’s existential terror, insignificance, and loneliness.

This statistic reflects the fearful atmosphere prevalent throughout the 1940s and Cold War. It’s depressing, lonely, and tough to connect with.

Gazing Head (1928)

| Date Completed | 1928 |

| Medium | Plaster |

| Dimensions | 40 cm x 36 cm x 6 cm |

| Current Location | Alberto Giacometti-Stiftung, Zurich |

Alberto Giacometti had a lot of trouble sculpting from life in his early years. In desperation, he started working from memory. The result of this attempt is the early plaster bust Gazing Head, which is possibly the artist’s first completely original piece.

The bust is both abstract and figurative because of the flattening of the face and head, as well as Giacometti’s economical use of smooth divots for defining.

Despite this, the work’s central motif, gazing, urges spectators to consider whether what they’re looking at is, in reality, a mirror. When Gazing Head was originally shown in Paris in 1929, it drew the attention of the French Surrealists, kicking off a relationship that would last for the rest of Giacometti’s career.

Suspended Ball (1931)

| Date Completed | 1931 |

| Medium | Cord, plaster, metal |

| Dimensions | 60 cm x 36 cm x 34 cm |

| Current Location | Fondation Giacometti, Paris |

Surrealists were drawn to Giacometti’s sculptures like Gazing Head, but it was Suspended Ball, originally shown at Galerie Pierre in 1930, that inspired André Breton to request Giacometti to represent the group. The white spherical form of the sculpture, which seemed to float freely while still being locked in a cage, as well as the cryptic portion underneath it, evinced the dream-like and sensual aspects that the Surrealists cherished. Influenced by Suspended Ball, Salvador Dalí wrote an essay on Surrealist artifacts for Breton’s journal following the 1930 group exhibition.

Despite Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures’ association with Breton’s collective, critics have linked them to the concepts of Breton’s rival, Georges Bataille.

The elements of the sculpture have been claimed to be purposely perplexing because, while they appear to depict a sex encounter, it is uncertain which element is masculine and which is feminine. Bataille’s concept of formlessness has been argued to be encapsulated by this tangle of categories.

Hands Holding the Void (1934)

| Date Completed | 1934 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 153 cm x 32 cm x 29 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

After his brief involvement with the Surrealists, Alberto Giacometti began to diverge from the group, as shown in this piece. It was produced as a memorial to the artist’s tragically deceased father, embodying “metaphysical reality,” as reviewer Carl Einstein put it. Certain prehistoric and Egyptian motifs are incorporated. The vacuum the figure is clutching might be the soul or kâ as it was known to the Egyptians.

The Surrealists welcomed this piece, yet the representational components show that the artist was moving beyond them.

City Square (1948)

| Date Completed | 1948 |

| Medium | Painted bronze |

| Dimensions | 24 cm x 64 cm x 43 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art, New York |

While not Alberto Giacometti’s first effort into the waif-like characters for which he is better known, the multi-figure City Square is a remarkable lesson in giving the sense of a large environment. The figures, which Sartre referred to as “moving outlines,” appear to emerge from nowhere as they walk across an empty environment.

Giacometti’s purpose is to place the link of man and environment with the earth,” Fairfield Porter said in a 1960 review for The Nation, “and he also sees mankind and everything else as a connection between the earth and infinity, with a dualistic connection to the environment.

By this time, Giacometti had studied Existentialism, and “City Square” may be read in that light, presenting humanity as a pale shadow of itself, living halfway between existence and nothingness.

Annette with Chariot (1950)

| Date Completed | 1950 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 50 cm x 73 cm |

| Current Location | Private Collection |

Although the sculpture is Giacometti’s most well-known media, he was also a skilled painter. This example of Alberto Giacometti’s paintings from 1950 demonstrates his ability to create a sense of tremendous depth on a flat surface.

The artist’s spouse, Annette, is the topic here, and she is constructed of the same arcs and dashes used to show the surrounding space as if she were simply another object.

Annette does, however, emerge discreetly from the arrangement, establishing her humanity despite the generally bland order of the space, much like Giacometti’s sculpted stick figures. Alberto Giacometti’s matured works had been an antidote to abstraction, as several of the prominent Existentialist philosophers of the time remarked.

Women of Venice II (1956)

| Date Completed | 1956 |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions | 120 cm |

| Current Location | Metro Museum of Art, New York |

“Man alone – degraded to a thread – in the disrepair and suffering of the earth – who seeks for oneself – beginning out of nothing. Man on a sidewalk like searing iron; who cannot raise his heavy feet,” Francis Ponge said in a 1951 piece for Cahiers d’Art. Like earlier paintings in a similar genre, Woman of Venice II depicts a solitary person, her body pummeled almost to the brink of collapse but yet standing tall and straight.

The topic of human decency and mankind’s desire to establish its presence in a huge world that seems bent on destroying it was at the core of such artworks.

Recommended Reading

Although this was a rather detailed article, there is always more to learn about any artist. Perhaps you would like to explore Alberto Giacometti’s paintings and sculptures even more. Listed are some books that can assist you in doing so.

Alberto Giacometti: Sculptures, Paintings, Drawings (1994) by Angela Schneider

The Swiss sculptor Alberto Giacometti, one of the great masters of twentieth-century art, expressed the existential isolation of contemporary mankind with his slender, emaciated figures whose lifelike gazes penetrate the expanse of space. This comprehensive book, which includes over 250 sculptures, paintings, sketches, and graphic pieces, is an outstanding survey of his work.

- Contributions by several notable art historians

- An exemplary overview of Giacometti's entire oeuvre

- More than 250 sculptures, paintings, drawings, and graphic works

Giacometti: Sculpture Paintings Drawings (2008) by Angela Schneider

Alberto Giacometti is most renowned for his lanky, attenuated figures, but he also made brilliant two-dimensional art. This book provides a thorough examination of his whole output, emphasizing the continuity between his pre-1935 works, which also included his Surrealist sculptures, and his postwar achievements. It describes Giacometti’s creative crisis, when he reverted to working from models and separated from the Surrealists, and how he started to approach the challenge of placing people in space in a whole new way.

- Offers a scholarly assessment of his entire oeuvre

- Featuring extraordinary images of the artist at work

- Discusses relationship between his two- and three-dimensional works

Alberto Giacometti is well known for his bronze sculptures of ghostly, emaciated figures, which helped him become a significant character in the Surrealist movement. World War II also happened to be a pivotal moment for Modernism as a whole. Giacometti started to focus on the head in 1936, concentrating on the figure’s gaze and ultimately gave his works an extruded aspect.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Alberto Giacometti?

Alberto Giacometti’s incredible career traces the changing passions for art in Europe both before and after World War II. In the 1930s, Alberto Giacometti’s sculptures displayed surrealist and inventive sculptural shapes, which were sometimes reminiscent of games and toys. As an Existentialist, Giacometti’s paintings after the war set the way for a form that reflected the philosophy’s interests in observation, solitude, and dread.

What Characterizes Alberto Giacometti’s Sculptures?

Following the war, parallel changes occurred in the artist’s work, with his frequently altered figures becoming increasingly gaunt and detached from their environment. He started to concentrate on extended single figures, frequently strolling or standing, as well as figural ensembles in various spatial contexts. Giacometti’s distinctive perspective reduced his themes to extensively wrought yet stick-thin forms.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Alberto Giacometti – Modernist Master of Elongated Form.” Art in Context. June 25, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/alberto-giacometti/

Meyer, I. (2022, 25 June). Alberto Giacometti – Modernist Master of Elongated Form. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/alberto-giacometti/

Meyer, Isabella. “Alberto Giacometti – Modernist Master of Elongated Form.” Art in Context, June 25, 2022. https://artincontext.org/alberto-giacometti/.