Henri Matisse – An Exploration of the Life and Art of Henri Matisse

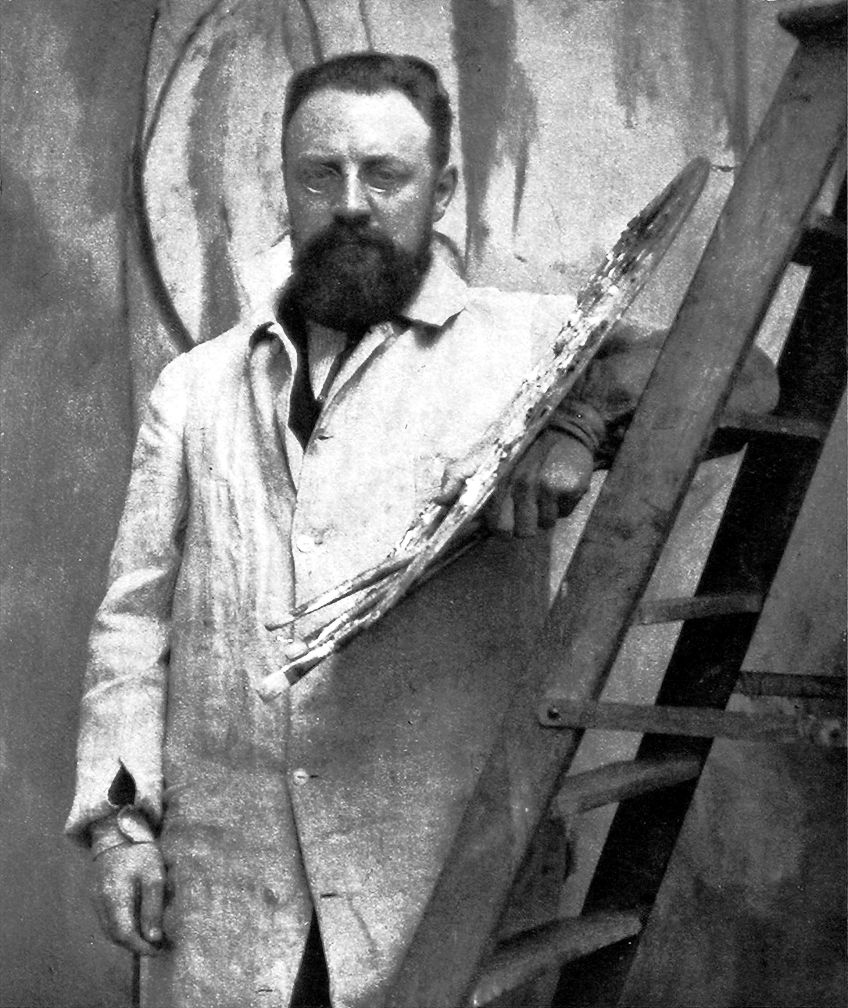

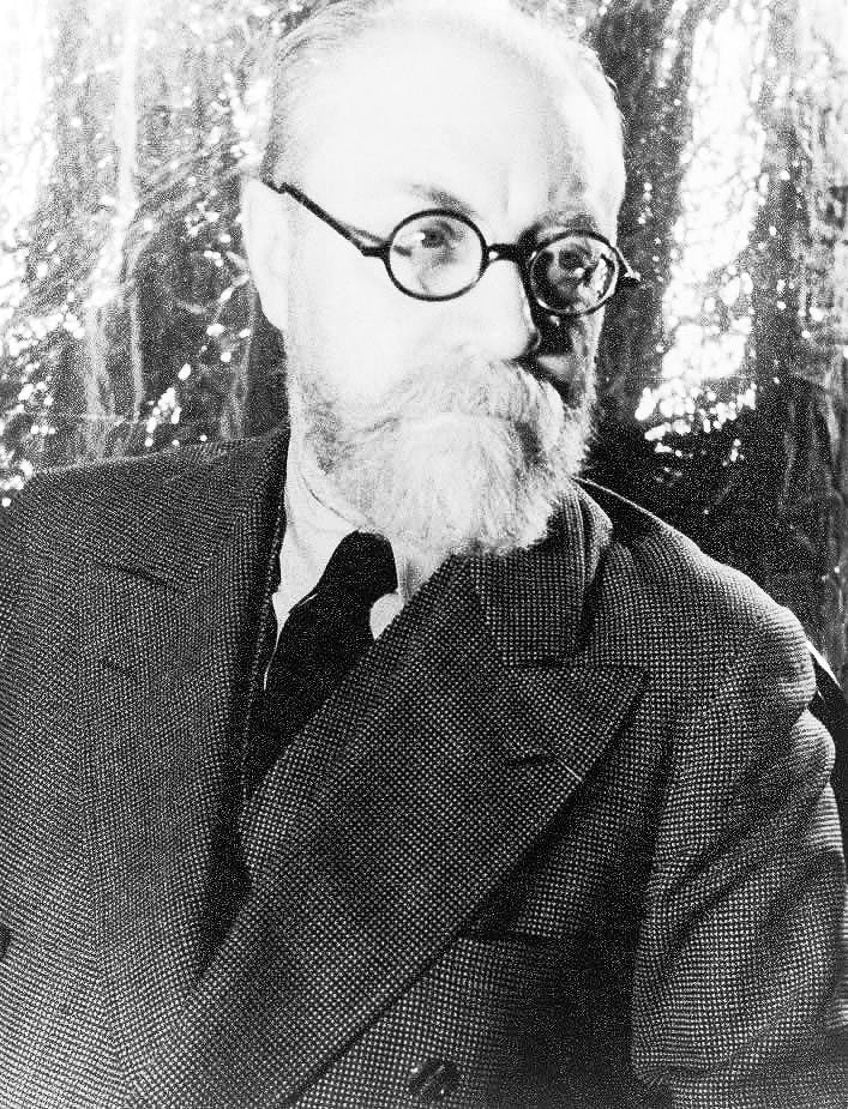

Henri Matisse is widely considered as one of the artists most responsible for defining the transformative advancements in the graphic arts during the first decades of the 20th century, accountable for key advances in sculpture and painting. Henri Matisse’s paintings gained him renown as a Fauve because of their strong colorism. Many of the finest examples of Henri Matisse’s artworks were made in the decade or so following 1906 when he established a disciplined style emphasizing flattened shapes and colorful patterns. Matisse the artist’s command of the evocative language of color and sketching, demonstrated in a body of work stretching more than a half-century, established him as a prominent figure in contemporary art.

A Henri Matisse Biography

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 31 December 1869 |

| Date of Death | 3 November 1954 |

| Place of Birth | Le Cateau-Cambresis, Picardy, France |

Matisse’s drawings and paintings were instrumental in advancing the significance of ornamentation in contemporary art. In works such as Matisse’s The Dance (1909), we are able to observe how important the human figure is to his creative output. Matisse’s portraits, such as The Woman with a Hat (1905), lambasted traditional portraiture.

Regardless of the fact that he is often recognized as an artist dedicated to delight and fulfillment, his employment of patterns and colors is frequently bewildering and unnerving. After 1930, he pursued a more daring form of simplification. When Matisse the artist’s health prohibited him from painting in his later years, he developed a significant oeuvre in the technique of paper collage.

Early Life and Education

Henri Matisse was born in the northern French town of Le Cateau-Cambrésis, the oldest son of a rich grain dealer. He began painting in 1889 after his mother sent him art equipment during a time of recuperation after an appendicitis episode. He discovered “a type of heaven,” as he later called it, and resolved on becoming a painter, much to his father’s chagrin. He returned to Paris in 1891 to pursue artwork at the Académie Julian with William-Adolphe Bouguereau. He began by painting still lifes and vistas in a classical manner, which he eventually mastered.

Matisse was influenced by earlier painters such as Antoine Watteau and Nicolas Poussin, as well as Japanese art and contemporary artists such as Édouard Manet. Chardin was among Matisse’s favorite artists; as a pupil, he copied four of Chardin’s works in the Louvre.

In 1896 when Matisse was largely still an unknown art scholar, he approached John Russell, the artist from Australia on the island of Belle Île off the coast of Brittany. Russell exposed him to Impressionism and the art of Vincent van Gogh, an acquaintance of Russell’s, and presented him with a Van Gogh drawing. Matisse’s approach shifted dramatically, discarding his earth-toned palette in favor of brilliant colors. He then claimed Russell was his instructor and that Russell had taught him about color theory.

In 1894, he had a child, Marguerite, with the beautiful Caroline Joblau. He wedded Amélie Noellie Parayre in 1898; the couple reared Marguerite jointly and had two sons, Pierre and Jean. Matisse frequently used Amélie and Marguerite as models. On the recommendation of Camille Pissarro, he traveled to London in 1898 to examine J. M. W. Turner’s works before traveling to Corsica.

In February 1899, he returned to France and collaborated with Albert Marquet, where he met Jean Puy, André Derain, and Jules Flandrin. Matisse engaged himself in the art of others, incurring debt in the process by purchasing works from artists he respected.

A plaster bust by Rodin, a Gauguin picture, a Van Gogh sketch, and Cézanne’s “Three Bathers” (1879 – 1882) were among the works he hung and exhibited at his house. Matisse discovered his major influence in Cézanne’s mastery of pictorial form and color.

The Humbert Affair, a massive financial scandal, engulfed Amélie’s parents in May 1902. Her parents were made scapegoats in the affair, and her family was threatened by hordes of irate fraud victims. “Their media scrutiny, followed by the incarceration of his father-in-law, left Henri Matisse the artist as the sole earner for an immediate family of seven,” noted art historians.

Matisse developed a painting technique that was somewhat dark and obsessed with form from 1902 to 1903, a transition that was probably meant to generate marketable paintings during this period of financial difficulties.

After attempting his first sculpture, a replica of Antoine-Louis Barye in 1899, Matisse spent most of his time and efforts working in clay, creating “The Slave” in 1903.

Mature Period

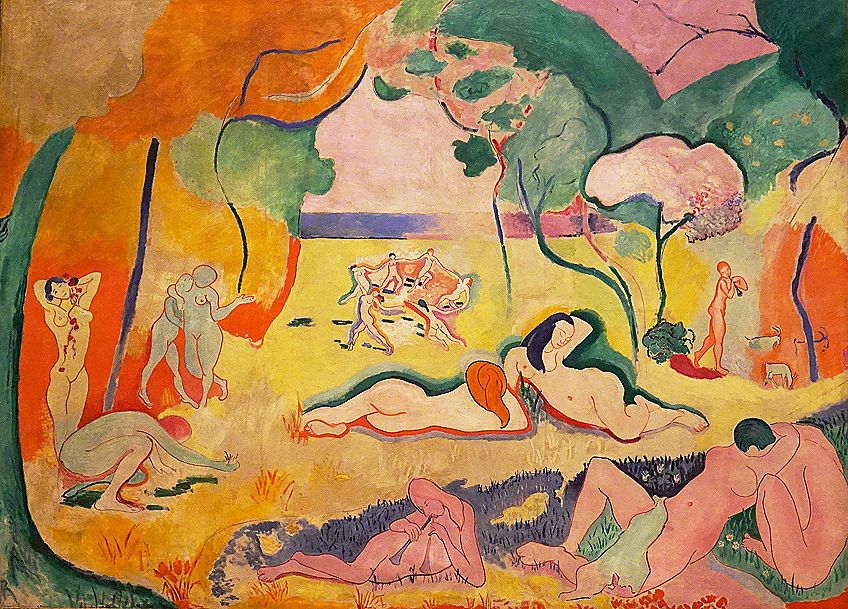

Fauvism as a genre emerged about 1900 and still existed after 1910. The group as a whole endured only a few years, from 1904 to 1908, and held three exhibits. Matisse’s debut solo show in 1904, at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery, was a disappointment. Luxe, Calme et Volupté, his most major neo-Impressionist masterpiece, was completed in 1904. In 1905, he returned south to collaborate with André Derain in Collioure.

His works from this time were distinguished by flatforms and restrained lines, and he employed pointillism in a less severe manner than previously. Matisse’s paintings used bold, often discordant colors to evoke emotion, with little respect for the subject’s inherent colors.

At the Salon d’Automne in 1905, Matisse displayed Woman with a Hat (1905) and Open Window (1905). Louis Vauxcelles, a reviewer, described a solitary statue encircled by a frenzy of pure tones as “Donatello amid the wild creatures”, alluding to a Renaissance-style work that occupied the space with them.

His remark was published in Gil Blas, a daily newspaper, on the 17th of October, 1905, and quickly became popular. The show drew scathing criticism—”a jar of paint has been thrown in the face of the people,” stated reviewer Camille Mauclair—as well as some positive notice. When Gertrude and Leo Stein purchased Matisse’s Woman with a Hat (1905), which had been singled out for special censure, the struggling artist’s mood improved noticeably.

Matisse, along with André Derain, was seen as a Fauve’s leader; the pair were amicable competitors, each with his own following.

Raoul Dufy, Georges Braque, and Maurice de Vlaminck were also members. Gustave Moreau, a Symbolist artist, was the movement’s inspiring instructor. As a lecturer at Paris’ École des Beaux-Arts, he encouraged his pupils to think outside the boundaries of formalism and to pursue their own ideals.

In a piece published in La Falange in 1907, Guillaume Apollinaire said of Matisse, “We are not here in the face of an excessive or radical endeavor: Henri Matisse’s artworks are entirely sensible.” However, Matisse’s art during the time was harshly criticized, and he struggled to support his family. Nu bleu (1907), one of his paintings, was destroyed in effigy in 1913 at the Armory Show in Chicago.

Matisse’s professional life was unaffected by the downturn of the Fauvists after 1906; many of the finest examples of Henri Matisse’s artworks works were produced between 1906 and 1917, at a time when he was an engaged member of the great assembling of creative skill in Montparnasse, despite his traditionalist looks and stringent bourgeois work ethic. He continued to be influenced by new things and in 1906, he traveled to Algeria to study Primitivism and African artworks.

In 1910, he spent two months in Spain researching Moorish art after seeing a huge exhibit of Islamic art in Munich. He returned to Morocco in 1912, and while there, he made various adjustments to his art, including the use of black as a color. The result was fresh confidence in the use of vivid, unmodulated color in Matisse’s paintings, as seen in L’Atelier Rouge (1911).

Sergei Shchukin, a Russian art collector, was a longtime friend of Matisse’s. He made one of his greatest pieces, Matisse’s The Dance (1909), for Shchukin as half of a two-part contract, the other being Music, 1910. An older rendition of Matisse’s The Dance (1909) is housed in New York City’s Museum of Modern Art.

Henri Matisse the artist met Pablo Picasso in April 1906. The two remained friends for life as well as adversaries, and their stories are frequently contrasted. One significant distinction between the two is that Matisse sketched and worked from nature, whereas Picasso preferred to work from his imagination. Women and still lifes were the most often painted topics by both artists, with Matisse more inclined to position his figures in completely realized interiors.

Picasso and Matisse first met at Gertrude Stein’s Paris salon with her partner Alice B. Toklas. In the first 10 years of the 20th century, American buyers and admirers of Henri Matisse’s artworks included Gertrude Stein, her siblings Leo and Michael Stein, as well as Michael’s spouse Sarah. Furthermore, Gertrude Stein’s two acquaintances from Baltimore, the Cone sisters Etta, and Claribel, were Picasso and Matisse’s main benefactors, amassing hundreds of Picasso and Matisse drawings and paintings.

Even though many artists frequented the Stein salon, many of them were not featured among the art on the walls of 27 rue de Fleurus. Contemporaries of the Steins, Matisse the artist, and Picasso, were part of their cultural circle and frequently attended Saturday evening events at 27 rue de Fleurus.

Matisse was credited for starting the Saturday evening salons.

According to Gertrude, “Visitors started to attend more regularly to view Matisse’s paintings – and the Cézannes: Henri Matisse brought people, everyone brought someone, and they arrived at any time, and it became an annoyance, but it was in this way that Saturday nights began.”

André Derain, Georges Braque, the poets Guillaume Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin, and Henri Rousseau were among Picasso’s friends who attended the Saturday nights. His friends created and funded the Académie Matisse in Paris, a private, non-profit institution where Matisse taught new painters. It was in operation from 1907 to 1911. The Steins and the Dômiers spearheaded the academy’s creation, with the help of Sarah Stein and Patrick Henry Bruce.

From 1912 until 1913, Henri Matisse spent the next seven months in Morocco, creating around 24 canvases and countless sketches. His later orientalist subjects, such as odalisques, may be linked back to this time period.

After Paris

His work from the decade or so after this migration demonstrates a loosening and easing of his style. This “returning to order” is typical of most post-World War I art, and may be likened to Stravinsky’s neoclassicism, as well as Derain’s return back to traditionalism.

While Matisse’s orientalism odalisque works were popular at the time, several contemporary reviewers thought them shallow and ornamental. Matisse resumed active partnerships with other painters in the late 1920s.

He collaborated not just with French people, the Dutch, Germans, and the Spanish, but also with a few people in the United States and recent American migrants. After 1930, his art took on a new vitality and bolder simplicity. American artwork enthusiast Albert C. Barnes persuaded Matisse to create The Dance II (1910), a massive fresco for the Barnes Foundation that was finished in 1932; the Foundation also possesses several dozen additional Matisse works.

This trend toward minimalism, as well as a premonition of the cut-out method, may also be seen in his work, “Large Reclining Nude” (1935). Matisse labored on this work for several months and sent Etta Cone a series of 22 images to track his progress.

The War Years

Matisse’s wife Amélie, who accused him of having an affair with Lydia Delectorskaya, a younger Russian immigrant, terminated their 41-year union in July 1939, splitting their belongings evenly. Delectorskaya attempted to commit suicide by trying to shoot herself in the breast; miraculously, she survived intact with no serious consequences and returned to Matisse to operate his residence, pay his bills, type his communications, keep detailed records, assist in the workshop, and coordinate his business operations for the rest of his life.

Matisse was in Paris when the Nazis seized France in June 1940, but he managed to return to Nice. His son, Pierre, a salon operator in New York at the time, encouraged him to depart while he could. Matisse was on his way to Brazil to flee the Occupation when he reconsidered and stayed in Nice. “It seems to me that I would desert,” he wrote to Pierre in September 1940. “What becomes of France if every one of value leaves?”

Although he was never a part of the resistance, it became a source of pride for the seized French that one of their most famous painters opted to stay, despite the fact that he, as a non-Jew, had that option.

During the Nazi occupation of France from 1940 until 1944, the Nazis were more indulgent in their assaults on “deviant art” in Paris than in the German-speaking countries under their military government. Matisse was permitted to exhibit alongside other former Cubists and Fauves whom Hitler had originally alleged to detest, but without any Jewish artists whose projects had been expunged from all French galleries and museums; any French creatives displaying in France had to accept an oath ensure their “Aryan” standing, including Matisse.

In 1941, Matisse was stricken with duodenal cancer. While the operation was successful, it resulted in terrible consequences that almost killed him. After being immobile for three months, he created a new art form out of paper and scissors.

Monique Bourgeois, a nursing student, answered Matisse’s post for a nurse. The two formed a platonic bond. He learned she was a budding painter and taught her the basics of perspective. Matisse occasionally approached Bourgeois after she quit the post to enter a convent in 1944 to pose for him. In 1946, Bourgeois became a Dominican nun, and Matisse dedicated a shrine to her in Vence, a tiny town he relocated to in 1943. All through the war, Matisse was mostly secluded in southern France, although his family was deeply engaged with the French resistance.

Matisse was astonished to learn that his daughter Marguerite, a member of the Résistance during the war, had been beaten by the Gestapo in a Renne’s jail and deported to a German concentration camp. Marguerite narrowly escaped from the Ravensbrück train, which was delayed by an Allied airstrike; she remained in the forests in the confusion of the final days of the war until she was rescued by other resistance fighters.

His son Pierre, a New York art dealer, assistant-Nazi French painters he promoted in fleeing seized France and entering the United States. In 1942, Pierre organized the famed “Artists in Exile” show in New York.

Final Years

Matisse was diagnosed with stomach cancer in 1941 and had surgery, which left him dependent on a wheelchair and frequently bed-confined. Sculpture and painting had become physically demanding, so he experimented with new media. He began making cut-paper collages with the aid of his assistants. He’d cut sheets of paper pre-painted with gouache by his helpers into shapes of varied colors and sizes, then arrange them to create vibrant compositions. Initially, these works were small in scale, but they gradually grew into murals or room-sized sculptures.

As a result, there emerged a unique and dimensional intricacies artistic medium that was neither painting nor sculpture. He referred to the latter 14 years of his life as “his second life.” When discussing his work, Matisse remarked that, despite his limited movement, he could travel around gardens in the shape of his artwork.

Although paper cut-outs became Matisse’s main medium in his final decade, his first acknowledged usage of the method was in 1919, when he designed the décor for Igor Stravinsky’s musical Le chant du Rossignol. Albert C. Barnes negotiated for cardboard templates of the unique size of the walls onto which Matisse fastened the arrangement of painted paper forms in his Nice workshop.

Matisse created another series of cut-outs between 1937 and 1938 while working on-stage costumes and sets for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. However, it wasn’t until Matisse was bedridden following his operation that he started to develop the cut-out method as its own expression, rather from its earlier utilitarian nature. In 1943, he relocated to the hilltop of Vence, France, where he completed his first big cut-out piece for his artist’s book named Jazz.

These cut-outs, on the other hand, were designed as patterns for stencil prints to be examined in the book, rather than as separate graphic pieces. Matisse still considered the cut-outs to be different from his main art form at this period.

With the 1946 debut of Jazz, he gains a new grasp of the medium. Matisse speaks to the potential of the cut-out method after recapping his career, stressing, “An individual must never be a slave of himself, slave of a technique, slave of a legacy, slave of achievement.” Following Jazz, the number of individually created cut-outs rapidly rose, eventually leading to the development of mural-size works such as 1946’s Oceania the Sky and Oceania the Sea.

Lydia Delectorskaya, Matisse’s studio helper, loosely pinned the outlines of fish, birds, and sea plants straight into the room’s walls. The two Oceania sculptures, his first cut-outs of this magnitude, were inspired by a trip he took to Tahiti years ago. His cutting The Sheaf was a triumph when it was displayed at the Salon de Mai in May 1954. Mr. and Mrs. Brody, American collectors, commissioned the artwork, which was later adapted to a ceramic for their Los Angeles home.

Matisse began preparing plans for the Chapelle du Rosaire de Vence in 1948, allowing him to explore this approach within a really ornamental framework. The experience of creating the chasubles, chapel windows, and tabernacle door—all of which were designed using the cut-out technique the effect of concentrating his attention on the medium.

Matisse used paper cut-outs as his main medium of expression until his demise in 1951, after completing his last canvas the year before.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rLgSd8ka0Gs

Despite his atheism, Matisse and Bourgeois had a strong connection that resulted in this endeavor. They reconnected in Vence and began working together again, as she recounted in her book. In 1952, he founded a museum dedicated to his art, the Matisse Museum in Le Cateau, which presently houses France’s third-largest collection of Matisse paintings.

Matisse’s final effort was the creation of a stained-glass window put in the Union Church of Pocantico Hills in the New York state. “It was his ultimate artistic endeavor; the maquette remained on the wall of his room when he passed in November 1954,” says Rockefeller. The piece was finished in 1956.

The Legacy of Henri Matisse

In the 1950s, scholars saw Fauvism and Matisse as forerunners of Abstract Expressionism and most of the modern art. Several Abstract Expressionists may trace their ancestors back to him, although for different reasons.

Some such as artists, like Lee Krasner, were affected by his varied mediums, as Matisse’s paper cut-outs prompted her to chop apart and reconstruct her own paintings.

Color field painters like Mark Rothko and Kenneth Noland were drawn to his large fields of vibrant colors, as seen in the Red Studio (1911). In contrast, Richard Diebenkorn was more concerned with how Matisse generated the perception of depth and the spatial and temporal tensions between his subject material and the surface canvas.

Others, such as Robert Motherwell, did not immediately demonstrate Matisse’s impact in their works but were impacted by his perspective on color in art. Marguerite Matisse, Matisse’s daughter, has provided insights into Matisse’s working techniques and works to Matisse researchers. She died in 1982 while working on a catalog of her father’s oeuvre.

Henri Matisse’s art continues to enchant not just artists, but also investors, who have paid up to $17 million for his paintings. And, as seen by multiple recent and impending blockbuster exhibits, he remains a public favorite across the world.

Henri Matisse’s Art Style and Techniques

Henri Matisse’s modern art approach helped pave the way for numerous noteworthy innovations in painting and sculpture throughout the early decades of the twentieth century. However, this was mostly owing to his application of revolutionary procedures.

The vivid colorism seen in several of Matisse’s style paintings between 1900 and 1905 earned him a place among the Fauves.

The bulk of his finest works was made in the decade after 1906. This year saw the birth of Henri Matisse’s newly created art style. This style emphasized the use of ornamental patterns and flattened shapes. Later that year, 1917, he moved to the French Riviera, near a neighborhood. His technique progressively evolved here, and the paintings became calmer and more tranquil.

After the 1930s, Henri Matisse’s art took on a stronger interpretation of form. He eventually developed health problems, at which point he was instructed not to paint. This is when he developed his signature style and produced a considerable body of work using cut-paper collages. Henri Matisse’s artwork style was perhaps the most admired, with this being one of his career’s pinnacles.

These days lasted barely a little more than a decade; it comprised 3 shows, one of which put its leader on the map, Matisse. This style was most recognized for its extravagant use of colors that had no real-world connection. The paint was applied erratically and haphazardly.

Notable Artworks

After Fauvism faded, one of Matisse’s most highly praised and iconic paintings came to completion. He began to instill the design aesthetic of Artwork from Africa and Primitivism in his students. He begins touring and is highly accepted everywhere he goes.

He was also a part of every major creative trend in Paris at the time. Some of his most renowned paintings date from this period, including Matisse’s The Dance (1909). Here are a few more of his important works:

- Luxe, Calme, et Volupte (1905)

- The Woman with the Hat (1905)

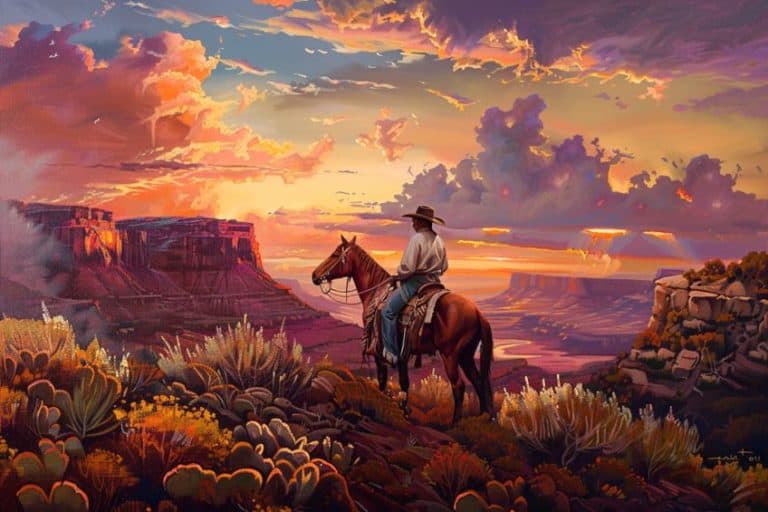

- Joy of Life (1906)

- Blue Nude (1907)

- The Back (1909)

- The Dance (1909)

- The Moroccans (1916)

- The Sheaf (1953)

Henri Matisse is widely regarded as one of the artists most important for defining the revolutionary breakthroughs in the graphic arts during the early decades of the 20th century, as well as being responsible for major improvements in sculpture and painting. Because of its vivid colorism, Henri Matisse’s paintings earned him a reputation as a Fauve. Many of Henri Matisse’s best works were created in the decade or so following 1906 when he developed a disciplined style stressing flattened forms and vivid patterns. Matisse the artist’s command of the emotive language of color and drawing, as evidenced by a body of work spanning more than a half-century, positioned him as a key figure in modern art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Matisse Known For?

Matisse’s sketches and paintings had an important role in expanding the importance of decoration in modern art. Despite the fact that he is generally seen as an artist committed to joy and fulfillment, his use of patterns and colors is frequently perplexing and unsettling. Aside from that, he is well-known for the collages that he created with paper cutouts. These compositions were in the final stages of his career, and he had already achieved sufficient praise by that point.

Why Did Matisse Make Cut-Out Art?

When contrasted to his earlier work, his way of work had altered dramatically in the final years of his life. Despite this, Matisse continued to paint until a misdiagnosis was made. He was afflicted with abdominal cancer in 1941 and had surgery. This further confined him to a bed and a chair, preventing him from painting or sculpting. He needed a fresh outlet, so he enlisted the aid of a handful of his subordinates and began constructing cut-paper collages.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Henri Matisse – An Exploration of the Life and Art of Henri Matisse.” Art in Context. March 15, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/henri-matisse/

Meyer, I. (2022, 15 March). Henri Matisse – An Exploration of the Life and Art of Henri Matisse. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/henri-matisse/

Meyer, Isabella. “Henri Matisse – An Exploration of the Life and Art of Henri Matisse.” Art in Context, March 15, 2022. https://artincontext.org/henri-matisse/.