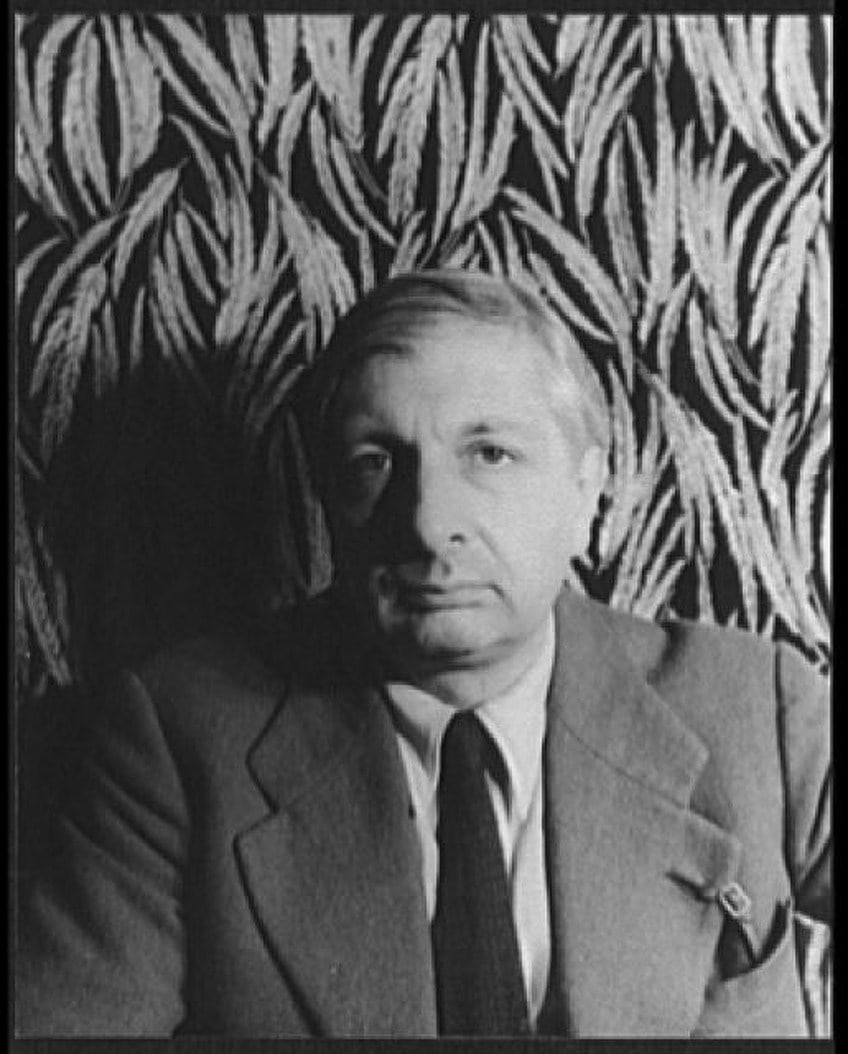

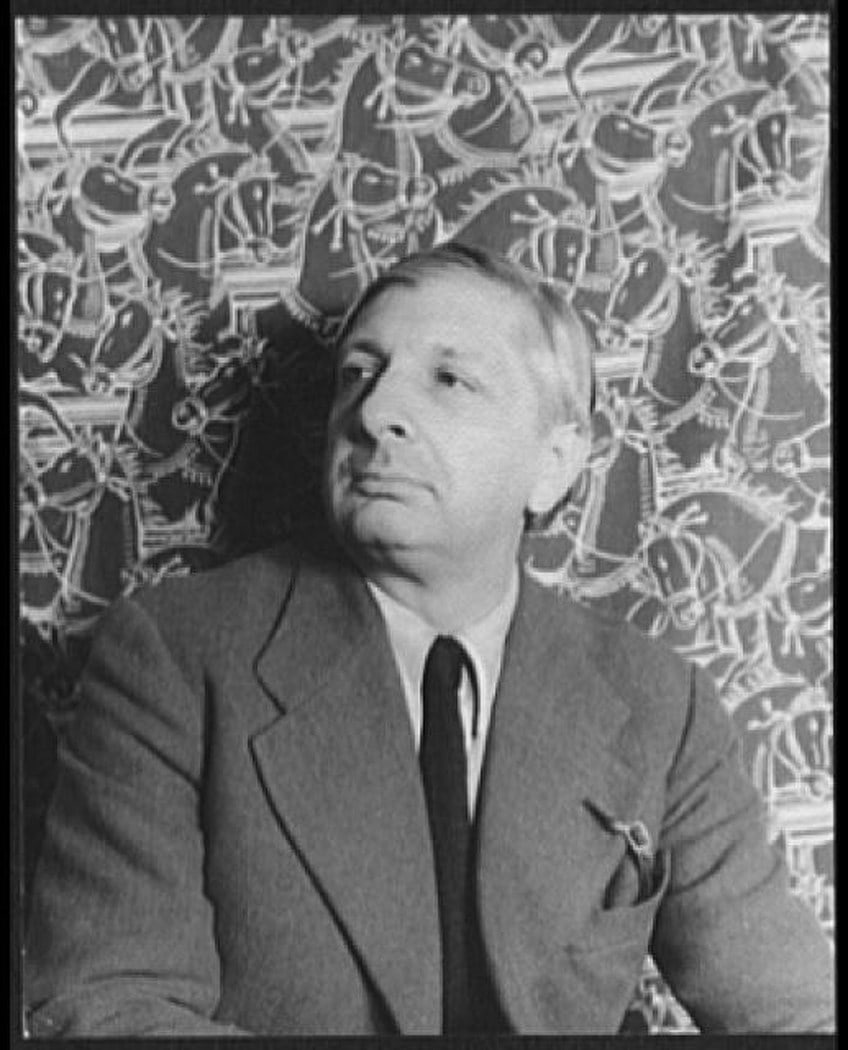

Giorgio de Chirico – One of the Top Famous Italian Painters

In the 1920s, Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings helped to pioneer the resurgence of Classicism, which became a pan-European movement. His homesickness during his time in Paris in the 1910s may have inspired the spooky, classically-influenced aesthetic of Giorgio de Chirico’s artworks of desolate town squares. His work from that era has resurfaced in recent years, and it was undoubtedly influential on a new school of famous Italian painters in the 1980s.

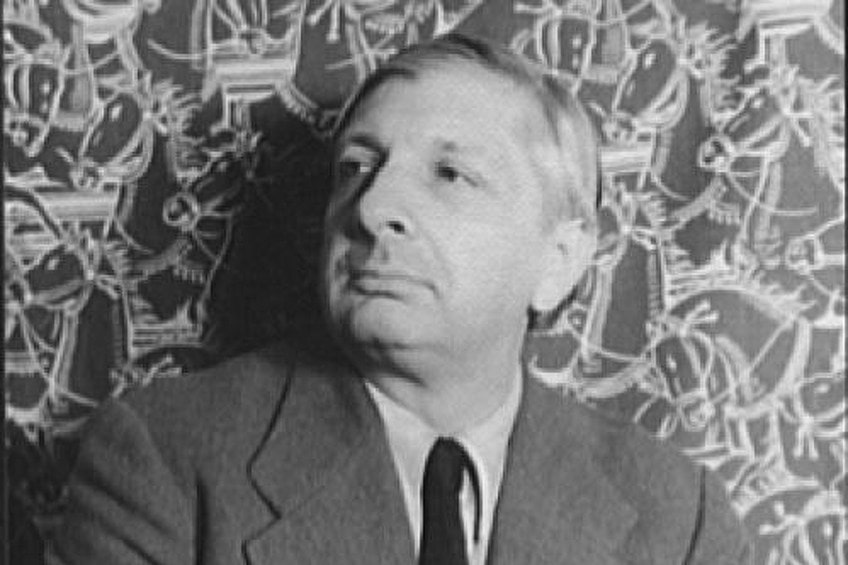

Giorgio de Chirico’s Biography

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 10 July 1888 |

| Date of Death | 20 November 1978 |

| Place of Birth | Volos, Greece |

The eerie tone and weird artificiality of De Chirico’s cityscapes from the 1910s made him renowned. Their major triumph is that he presents the images as haunting streets we could find in nightmares, rather than traditional cityscapes – as viewpoints on places full of bustle and everyday happening. They serve as settings for pregnant symbolism or even groups of things that approach still lifes at times.

Critics have referred to these films as “dream scripts” because of De Chirico’s inventive approach to them, which is similar to that of a dramatic set designer.

Childhood

Giorgio de Chirico was born to Italian parents in Volos, Greece. His father did engineer work on the Greek railway system, and his mother was a Genoese socialite. His parents fostered his creative growth, and he had a deep interest in Greek mythology at a young age, maybe because Volos was the port from where the Argonauts were meant to set sail to reclaim the Golden Fleece. Intestinal problems plagued him as a child, and it’s been suggested that this added to his melancholy disposition.

Early Training

De Chirico attended Athens’ Higher School of Fine Arts from 1903 to 1905. The family traveled to Florence when his father died in 1905 before going to Munich the next year. De Chirico studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome, where he became fascinated by Symbolist artists such as German Max Klinger. In March 1910, he returned to his family in Milan after graduating from Munich. He traveled to Florence soon after and began studying German thinkers like Friedrich Nietzsche and Otto Weininger through Italian author Giovanni Papini.

De Chirico endeavored to connect these men’s works to his own painting, hoping to look beyond the mundane aspects of everyday life to the actuality that he felt lay beyond.

Mature Period

Throughout his career, Giorgio de Chirico’s paintings featured historical, mythical, and philosophical subjects. His Metaphysical Town Square series began. There are recurring themes of recollection, grief, mystery, the passage of time, and architecture – notably arches and spires – in barren, sad squares and cityscapes throughout this era, which lasted until 1919.

They look to be visions of deserted Mediterranean cities from a time outside of history, where mythology pervades everyday life.

In July 1911, De Chirico and his mother traveled to Paris to join his brother, passing through Turin on the route. He was intrigued by the city since it was there that Nietzsche first showed indications of psychosis in 1889.

The architecture of the courtyards and arched windows had a big influence on him, and you can see spots in the city in his works from this time period.

De Chirico and his brother enlisted in the Italian army to defend their country in World War I in May 1915. De Chirico proceeded to paint in Ferrara, with the city’s arches and store windows featuring in his paintings. He started using mannequins in his Parisian works, and they became increasingly common in his Ferrara works.

In 1917, a mental ailment led him into an institution, where he proceeded to create, primarily in the Metaphysical style, with crowded interiors. He met Carlo Carrà in the hospital, and their conversations gave birth to Metaphysical painting. De Chirico held his first solo display at the Galleria Bragaglia in Rome in early 1919.

Late Period

De Chirico’s final period of work is generally thought to have begun in 1919 and ended in 1978. He had a breakthrough in 1919, just after his first solo display, while pondering a Titian work at Rome’s Galleria Borghese. He published an article advocating a return to old methods and iconography while also initiating an ardent anti-modern art crusade. De Chirico had previously shown little interest in the technique. Despite his background, his early representational work displayed a lack of anatomical expertise.

He focused on his style and was influenced by the Old Masters while in Rome, especially between 1919 and 1924.

De Chirico’s art also expanded into various mediums at this time. He worked on drawings for a ballet based on a short play by Italian writer Luigi Pirandello in Paris in 1924. In 1929, he created lithographs for a reprint of Guillaume Apollinaire’s poetry collection Calligrammes. Hebdomeros, his sole novel, was published the same year.

Despite his creative shift, the dream-like compilation of experiences and settings in the book serves as a literary complement to his metaphysical artworks.

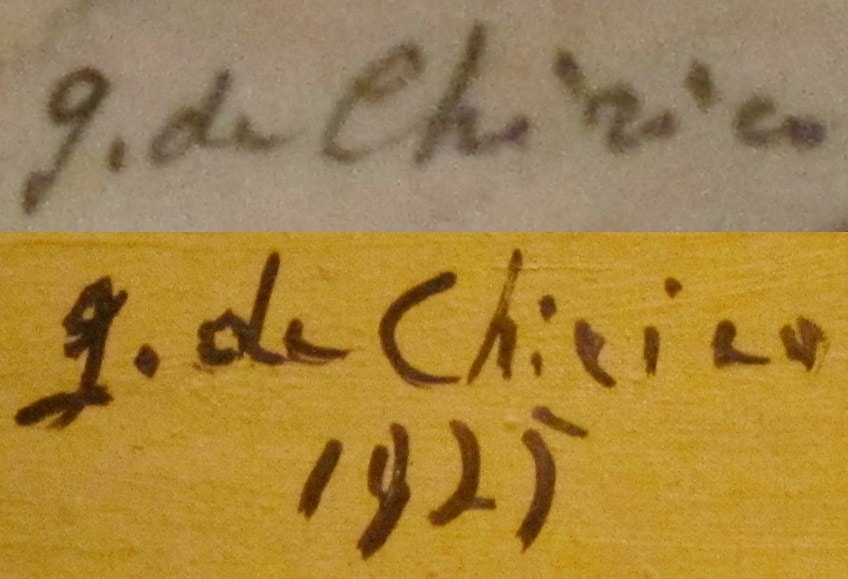

Despite the fact that De Chirico had removed himself from the Surrealists by this period, Hebdomeros remains one of the best instances of Surrealist writing. He pursued such endeavors till the end of his life. He began making miniature bronze sculptures in the late 1960s, some of which featured figures from his previous paintings, such as the mannequins from his Ferrara time. He would manufacture and sell reproductions of works from his Metaphysical phase for the remainder of his career, passing them off as original versions.

The tactic was part of an effort to benefit from the success of his early works and part of vengeance against the reviewers who praised it while criticizing his subsequent eras’ styles.

Legacy

Despite de Chirico’s 70-year career, his early metaphysical pieces remain his most important. He influenced the Surrealists greatly. De Chirico was one of the principal torchbearers of a new contemporary mythology, according to André Breton. He was initially pleased to be pursued by the Surrealists, but he eventually derided them as “leaders of modernistic idiocy.”

Nonetheless, he served as an influence for later French avant-garde organizations such as the Situationists, notably in terms of urbanization.

These two groups regard de Chirico as an architect as much as an artist, finding visions and designs for future cities in his cryptic piazzas and towers. Apart from the art world, de Chirico’s impact may be found in anything from Michelangelo Antonioni’s images of lonely cityscapes and urban alienation to the surroundings and branding for the Playstation videogame Ico.

Achievements

The adoration of the classical past is central to Giorgio de Chirico’s artworks. He became interested in this because of his admiration for German Romanticism, which opened him to fresh perspectives on the Classics and new approaches to themes of tragedy, riddle, and sadness. Themes and ideas from the Greco-Roman classics, according to de Chirico, were still relevant in the current world.

However, he discovered that juxtaposing the past and present caused unusual effects, such as sadness, confusion, and nostalgia, and that presenting this contrast produced some of his artwork’s most dramatic aspects in the 1910s.

The controlled purity of his approach accounts for much of the impact of de Chirico’s paintings.

He did it by abandoning the formal changes that have characterized most modern art since Impressionism in favor of a straightforward, realistic style that allowed him to describe objects simply. The outcome is a style that, like René Magritte’s, is full of seductive intrigue despite the depiction’s simple nature.

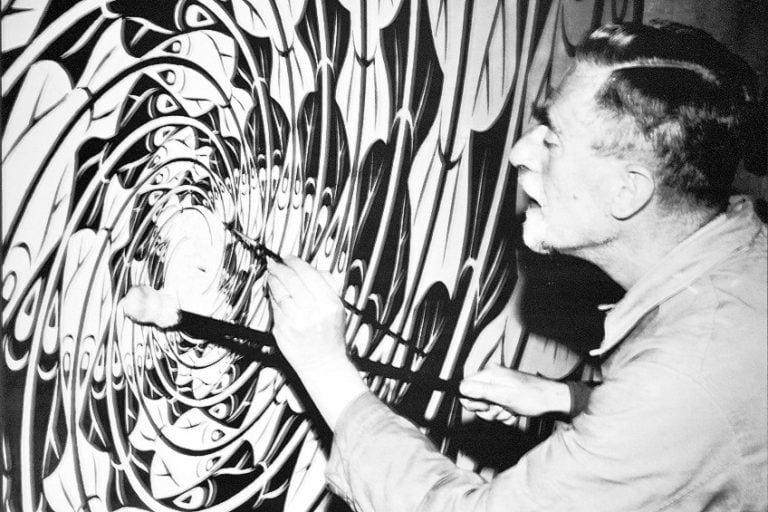

Giorgio de Chirico’s Paintings

De Chirico always thought that his early academic knowledge was essential in training him for his subsequent study, and this conservative stance placed him apart from other famous Italian painters, notably the Surrealists who helped enhance his renown. This outlook evolved into a reinvigorated faith in the significance of artisanship and the Old Masters’ heritage in the 1920s, resulting in a transition in his aesthetic toward better detail, fuller color, and more classically precise modeling of shapes and volumes, including more direct references to Baroque and Renaissance art.

The Enigma of an Autumn Afternoon (1910)

| Date Completed | 1910 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 80 cm x 59 cm |

| Current Location | Peggy Guggenheim Collection |

This is the first artwork in the Metaphysical Town Square series, and the first work in which he established his signature style and iconography – peaceful, cryptic, curiously reduced images of old cities. It’s also the first of a series of paintings with the term “enigma” in the title.

We might infer that the riddle in issue is the connection between the real and the unreal, as this painting was created after the artist experienced an epiphany at Florence’s Piazza Santa Croce, in which the world emerged before him for the first time.

The artwork represents a reduced version of that square. It contains many of the elements that would come to define his works: a deserted plaza surrounded by a classical facade, the long shadows and deep hues of the city at sunset, and a motionless figure, in this case, a statue. The sail discernible in the background may have been influenced by de Chirico’s childhood excursions to the Greek harbor of Piraeus.

The Child’s Brain (1914)

| Date Completed | 1914 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 81 cm x 65 cm |

| Current Location | Modern Museum, Stockholm |

This was a beloved of Surrealism’s creator, André Breton, who reputedly acquired the artwork after seeing it in a gallery window forced him to get off his bus. For over 10 years before the Surrealists began to speak about the significance of dreams and the subconscious, de Chirico was producing pictures like these that spoke about precisely these topics.

In chats with de Chirico, Breton said, the painter divulged that the man shown in this portrait was his father.

The bookmark in the novel on the table represents his parents’ copulation, with the bookmark placed to symbolize the phallus. On some other level, the gentleman in the picture is a portrayal of the youthful, sexually conflicted, and virile Dionysus, whether based on de Chirico’s father or not.

Breton and the Surrealists analyzed de Chirico’s paintings using psychoanalytic readings, yet Freud was unfamiliar with de Chirico until sometime in the 1920s.

Gare Montparnasse (The Melancholy of Departure) (1914)

| Date Completed | 1914 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 140 cm x 184 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

The prominence of the architecture is fundamental to its potency, but it is de Chirico’s treatment of the architecture that is so original; it is not intended to reflect a specific place or setting, but rather to function as a theatrical set – an unreal background for unreal actions. Its use of several vanishing points, rich hues, and prolonged dusk shadows is typical of the artist’s work from the 1910s. The leaving train and clock tower may foretell his impending leave to serve in the Italian army in World War One.

Trains appear often in Giorgio de Chirico’s artworks, serving as a metaphor for life and young expectation.

The Disquieting Muses (1916)

| Date Completed | 1916 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 97 cm x 66 cm |

| Current Location | Private Collection |

Another common theme in de Chirico’s paintings is that of the muses. He thought they motivated the artist to explore beyond the tangible and into the metaphysical realms of recollection, myth, and truth. The Disquieting Muses was created about 1917 while he was residing in Ferrara; the city’s Castello Estense may be seen in the backdrop.

This would eventually come to serve as the basis for a poem of the same name by Sylvia Plath.

Once more, de Chirico disregards architectural scale and appears to depict it almost as a tiny model in which he may insert the symbolic items of an unsettling still life. There are at least 18 copies of this artwork that have been backdated by the painter to claim that they were created in the late 1910s, precisely like this one.

The habit of manufacturing such duplicates and backdating them was part profiteering and part retaliation against critics who criticized his later works.

Great Metaphysical Interior (1917)

| Date Completed | 1917 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 96 cm x 70 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

This is one of the metaphysical interiors produced during the last portion of his life in Ferrara. It, like the other pieces in the series, depicts a chaotic room with a variety of artifacts, including other framed photos, and was inspired by his trips around the city’s arcades. The contents of the chamber are rather suggestive, but given that food appears frequently in de Chirico’s work from this era, it’s possible that the baguettes laying in a coffin-like box are an allusion to his digestive difficulties.

Giorgio De Chirico’s Self-Portrait (1922)

| Date Completed | 1922 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 38 cm x 51 cm |

| Current Location | Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio |

Giorgio de Chirico’s Self-portrait is a painting that represents the artist’s soul-searching era. It depicts de Chirico with a self-portrait bust. While the statue looks at him blankly, the painter is turned slightly to the observer, staring at us with a disturbing glare. They’re both closely cropped, making them appear gigantic, while the little tangerine in the front further adds to their enormity. We are not able to view much of the environment behind them, however, the lonely structure placed against a green sky looks akin to de Chirico’s metaphysical works.

What’s intriguing about this piece is that it’s not just a double self-portrait, but the artist shows himself as both an object and a subject.

Eventually, the subject has become an object as well — that is, the picture itself. What do you think about that? However, what I actually mean by all of this object/subject rhetoric is that there is a close link between an artist and their work; they may easily overlay and penetrate one another. The artist creates the art, but the art comes to characterize the artist as well. The statue in the painting can be viewed as the most concrete and long-lasting self-representation an artist can make, but in de Chirico’s case, statues are much more. They signify wisdom, civilization, tradition, and a return to figurative painting, which he believes has been neglected.

In his articles, he encourages painters to visit sculptures: “Yes, to the statues to acquire the dignity and religion of painting, to the sculptures to degrade you a little, you who were still too human despite your puerile devilries.”

De Chirico never lost his enthusiasm and persistence for adopting ancient techniques when he broke away from the Surrealists – who, in the early 1920s, were finally acknowledging the relevance of his metaphysical works – and embraced a style incorporating Baroque and Romanticism. Instead of grabbing the future, de Chirico stayed stationary in the middle of a flurry of revolutionary art trends.

Recommended Reading

We have tried to cover the fundamental aspects of Giorgio de Chirico’s biography and art. Yet, there is so much more we can learn about his amazing artwork. Here are some essential books to help you discover more about his artworks and life.

The Memoirs of Giorgio De Chirico (1994) by Giorgio de Chirico

No Italian painter of the 20th century has sparked as much debate, ranging from adulation to harsh criticism, as Giorgio de Chirico. He is an important character in contemporary art and one of the founders of surrealism; his effect on other artists, particularly during his “metaphysical” era, was enormous. De Chirico used imagery from the unconscious to produce art with mythical, philosophical, and social implications, giving his works more than just aesthetic appeal.

- A self-portrait on one of the most famous Italian Surrealist painters

- A projection of the obsessions and inner conflicts of the artist

- The memoirs of the famous Italian painter, Giorgio de Chirico

Giorgio de Chirico: The Changing Face of Metaphysical Art (2019) by Victoria Noel-Johnson

Victoria Noel-Johnson investigates the creator’s whole, multifaceted work and provides a unified logic within its multiplicity in the first de Chirico analysis in more than 20 years. Noel-Johnson contends that, notwithstanding the de Chirico’s many adjustments in style, methodology, subject, structure, and tonality over 60 years, all of his creations can provide meaningful imaginings of unquantifiable philosophical ideas by arranging the creator’s projects contextually and reciting them through the Nietzschean ideology to which the painter was notably dedicated.

This lavishly illustrated volume includes pieces from the artist’s foundation as well as some of Italy’s most prominent institutions and collections, as well as a rich core of archive documents like letters and vintage pictures.

Around 1911, Giorgio de Chirico began to create his Metaphysical painting, painting melancholy, dreamlike vistas of depopulated landscapes filled with strange artifacts. Despite the fact that this is the work for which de Chirico is most known, his “Metaphysical Painting” era only lasted until 1919, although he remained productive and adventurous throughout his long life. Between 1909 and 1911, he traveled to Milan, Florence, and Turin, where he was influenced by the brilliant Mediterranean sunlight, sun-drenched promenades, and retreating arcades – characteristics that would become crucial visual themes in his best-known paintings.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Giorgio de Chirico?

Giorgio de Chirico is mainly remembered as a co-founder of the Scuola Metafisica art scene, which flourished in Italy at the beginning of the twentieth century. He explored the complexities of the mind with frightening, dreamy images of low-lit town squares inhabited by marble sculptures, trains, dummies, and stretched shadows. The artist purposefully warped perspectives and flattened forms into flat surfaces. De Chirico had a strong effect on the Surrealists, notably Salvador Dalí, André Breton, and René Magritte, but while they were inspired by Freudian psychoanalysis, de Chirico acknowledged the ideas of Arthur Schopenhauer and Friedrich Nietzsche as his major influences. De Chirico’s art may now be found in the Tate, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection, among other places.

What Legacy Did Giorgio de Chirico Leave Behind?

Despite his 70-year career, de Chirico’s early metaphysical works remain his most important. He had a significant impact on the Surrealists. According to André Breton, De Chirico was one of the primary torchbearers of a new modern mythology. He was thrilled to be sought by the Surrealists at first, but he soon denounced them as leaders of modernistic foolishness.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Giorgio de Chirico – One of the Top Famous Italian Painters.” Art in Context. June 1, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/giorgio-de-chirico/

Meyer, I. (2022, 1 June). Giorgio de Chirico – One of the Top Famous Italian Painters. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/giorgio-de-chirico/

Meyer, Isabella. “Giorgio de Chirico – One of the Top Famous Italian Painters.” Art in Context, June 1, 2022. https://artincontext.org/giorgio-de-chirico/.