Arts and Crafts Movement – A Revolutionary Style of Design

Recognized as an international style of decorative and fine art, the Arts and Crafts movement was initially developed and most fully formed in the British Isles, after which it spread all throughout the British Empire, as well as the other regions in Europe and the United States. The Arts and Crafts style embraced folk, medieval, and romantic aesthetics and traditional craftsmanship, eschewing the industrial nature of the modern era. This style encompassed decorative arts as well as Arts and Crafts architecture. Let’s find out more below, as we explore various Arts and Crafts movement examples, its history, and its prominent members.

An Introduction to the Arts and Crafts Movement

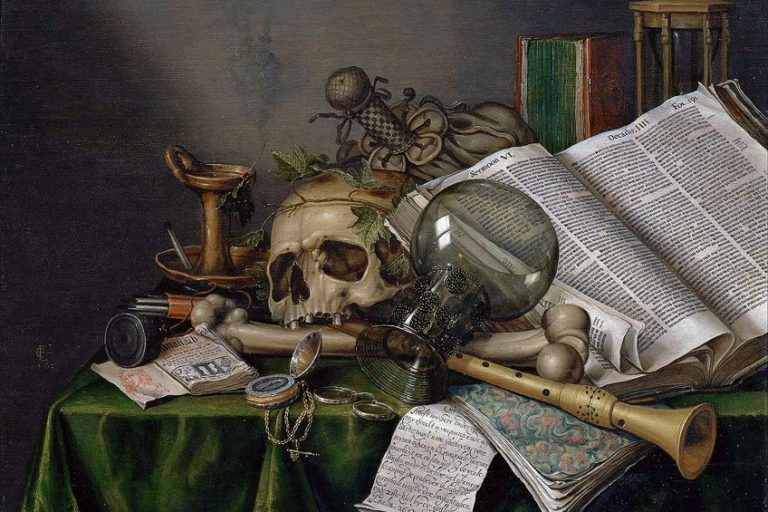

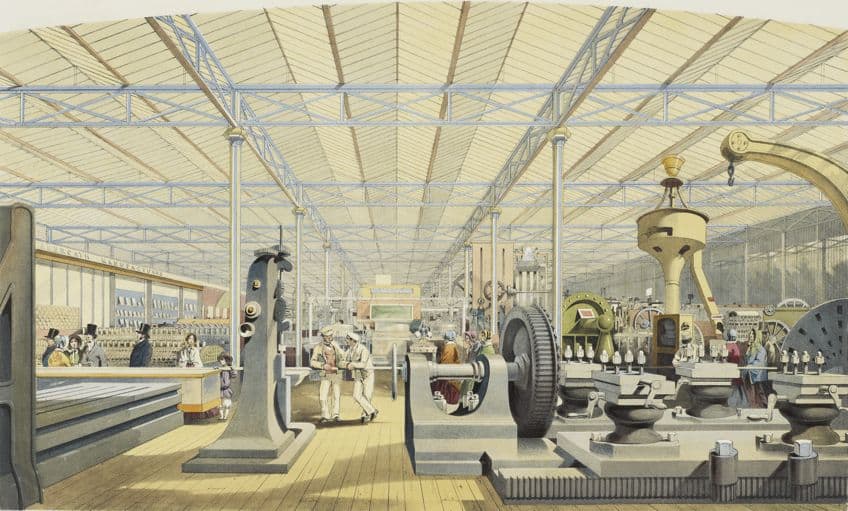

This movement first arose from a mid-19th-century British desire to modernize decoration and design. It was a response to the reformers’ view that there was a decline in standards relating to factory machinery and its output. Their criticism was further heightened due to the displayed objects that they encountered at the 1851 Great Exhibition, which they perceived as too extravagant, artificial, and uninformed of the properties of the materials that had been used.

Design Reform

Design reform started with Exhibition organizers Owen Jones, Henry Cole, Matthew Digby Wyatt, and Richard Redgrave, who all despised excessive ornamentation and unworkable or poorly built objects. For instance, Owen Jones claimed that the upholsterer, architect, calico-printer, weaver, and potter, created innovations without beauty, or beauty without intellect. Several publications developed from these criticisms of the produced objects, outlining what the writers thought to be the ideal design principles. The Supplementary Report on Design (1852) by Richard Redgrave examined the concepts of design and ornamentation and argued for more rationale in the use of decoration.

Jones stated that decoration must be secondary to the item adorned, that it must be suitable to the item, and that carpets and wallpapers shouldn’t have any patterns indicating anything other than a plain or level.

In the Great Exhibition, textiles or wallpaper often incorporated decorations with a natural theme that was designed to be as authentic as possible, but these writers argued for flat and simple natural designs. Redgrave emphasized that “style” required solid construction of an item before its adornment, as well as an understanding of the quality of the materials used. In their eyes, the utility of an object must take precedence over its decoration.

Nevertheless, the mid-19th-century reformers in design failed to advance as far as the Arts and Crafts movement’s architects and designers. They were more preoccupied with adornment than with building, had insufficient knowledge of manufacturing processes, and did not criticize industrial practices in general. By comparison, the Arts and Crafts movement was considered to be as much a movement for social reform as it was a movement for the reform of design, and its main adherents didn’t distinguish between the two.

The Influence of Augustus Pugin

Augustus Pugin, a pioneer in the Gothic revival in architecture, foreshadowed some of the Arts and Crafts movement’s principles. Pugin, as with the Arts and Crafts artisans, pushed for material, structural, and functional truth in production. Pugin highlighted the inclination of social critics to link modern society’s flaws to those of the Middle Ages, such as vast city expansion and how the poor were treated – a belief that became popular with Morris, Ruskin, and the Arts and Crafts movement. Pugin’s book Contrasts (1836) juxtaposed unfavorable modern buildings and town planning with exemplary medieval examples, and Rosemary Hill, his biographer, observed that he came to conclusions about the significance of tradition and craftsmanship in architecture essentially in passing that would require the remainder of that century and the collaborative efforts of Morris and Ruskin to flesh out in detail.

Hill defines the minimalist furniture he chose for a specific building in 1841, such as the wood tables and rush chairs, as the embryonic Arts and Crafts interior.

The Influence of John Ruskin

The Arts and Crafts ideology was heavily affected by John Ruskin’s social critique, which was in turn heavily impacted by Thomas Carlyle’s work. Ruskin attributed a nation’s social and moral health to the features of its architecture and the essence of its labor. Ruskin saw the industrial revolution’s mechanical production and division of labor as slave labor, and he believed that a moral and healthy society required autonomous workers who also designed the products they manufactured. He considered factory-made products to be “dishonest”, and he felt that craftsmanship and handwork combined dignity and labor. His supporters preferred handcrafting to industrial manufacturing and expressed concern about the possible disappearance of traditional skills, although they were more preoccupied with the impacts of the factory system than with the technology itself. William Morris defined “handicraft” as “work devoid of any division of labor” instead of “work without any kind of machinery.

The Influence of William Morris

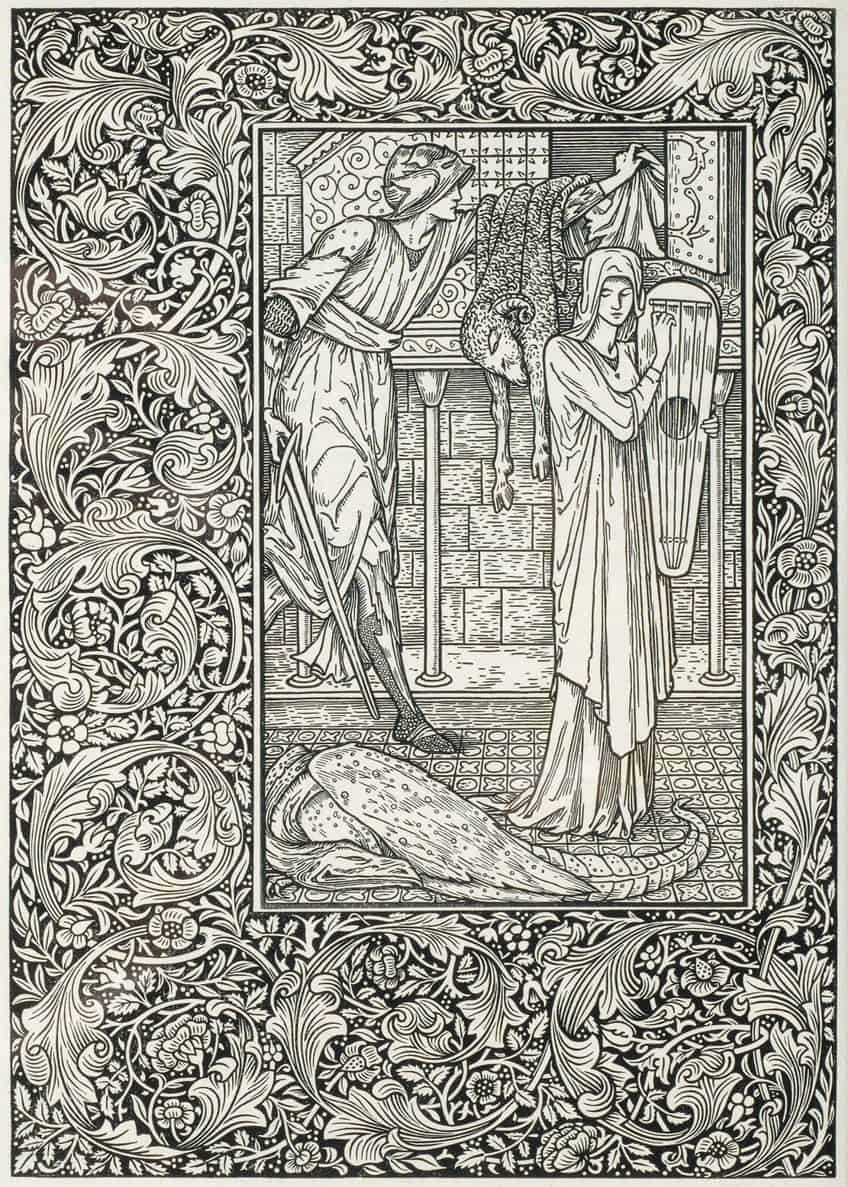

Morris was regarded by many as playing the most pivotal role in the design styles of the late 19th century and had a major impact on the Arts and Crafts movement. A group consisting of pupils of the University of Oxford known as the Birmingham Set, including Edward Burne-Jones, incorporated their appreciation of Romantic literature with a dedication to social change, inspiring the movement’s aesthetic and social vision. Morris started to experiment with other crafts and create furniture and decor. Morris was involved in both manufacturing and design, as was typical of those working within the Arts and Crafts movement.

The separation of the intellectual process of design from the hands-on act of physical production, according to Ruskin, was both culturally and artistically detrimental. Morris expanded on this concept, insisting that nothing be done in his workshops until he had personally mastered the necessary skills and materials, believing that without respectable, creative human labor, individuals start to disconnect from life.

Morris started professionally producing furniture and ornamental items in 1861, basing his creations on medieval influences and employing bold shapes and bright colors. His designs were influenced by nature and animals, and his goods by domestic or vernacular traditions of the British countryside. Some were purposefully left unfinished to emphasize the intrinsic beauty of the materials used in addition to the craftsmanship of the artisan, resulting in a rustic appearance. Morris aimed to include all of the arts into home décor, focusing on nature and purity of form.

Design and Social Principles of the Arts and Crafts Style

William Morris supported Ruskin’s criticisms of an industrial society and opposed the modern factory, the division of labor, the use of equipment, capitalism, and the decline of traditional craft techniques. However, Morris’ attitude toward industrial machinery was not very consistent. At one point, he stated that machine manufacturing should be considered “an evil” practice, yet, on other occasions, he was prepared to commission work from factories that could fulfill his requirements with the help of machines. Morris claimed that in a “proper society”, wherein neither cheap garbage nor luxuries were produced, machines could be developed and used to minimize labor hours.

So long as these machines deliver the quality he required, it seems that William Morris did not have practical objections to their use.

Focus on the Middle Ages

Morris, however, emphasized that the artist should be a craftsman-designer who worked by hand and promoted a society of free crafters, similar to what he thought must have occurred throughout the Middle Ages. Morris believed that the Middle Ages were an era of excellence in common people’s art because artisans took great pleasure in their work. A great deal of Arts and Crafts design was inspired by medieval art, and the movement idealized medieval life, literature, and architecture.

No Division of Labor

Morris and his supporters argued that the division of labor on which modern industries relied was unfavorable but the degree to which every design ought to be executed by the designer was a topic of contention. Not every Arts and Crafts artist handled every stage of the manufacturing process personally, and it wasn’t until the 20th century that this became a prerequisite for the concept of craftsmanship. Although Morris was well-known for acquiring practical knowledge in a variety of crafts, including dying, weaving, calligraphy, printing, and embroidery, he did not see the division of labor between designer and crafter as an issue in his factory. Walter Crane, Morris’s close political companion, was opposed to the division of labor for ethical and artistic reasons and argued that the designing and creating aspects should all be done by the same hand. Crane’s contemporary and friend, Lewis Foreman Day, fiercely disagreed with him.

He believed that the division of the two processes was not only inevitable in modern society, but that it was also the only way to achieve the best in both design and manufacturing.

The Development of the Arts and Crafts Movement

Morris’s designs quickly rose to popularity, gaining recognition when his company’s craftsmanship was displayed at the International Exhibition in 1862. Despite his desire to establish a democratic kind of art, Morris’ work later grew in popularity with the middle and upper classes, and towards the last years of the 19th century, Arts and Crafts architecture and interiors were the most prominent styles in Britain, replicated in items created using traditional industrial processes. The development of Arts and Crafts styles and concepts in the latter part of the 19th and the start of the 20th centuries led to the formation of several organizations and craft communities, albeit Morris had limited involvement with them due to his obsession with socialism at the time.

In Britain, 130 different Arts and Crafts organizations were founded, the majority emerging between 1895 and 1905. By the close of the 19th century, the principles of the Arts and Crafts movement had a significant impact on the decorative arts, including woodworking, furniture, stained glass, lacemaking, leatherwork, embroidery, weaving, metalwork, jewelry, ceramics, and enameling, as well as painting, sculpture, architecture, graphics, book production, photography, and illustration. By 1910, the Arts and Crafts style and everything done by hand was in vogue.

The general public came to view Arts & Crafts as less competent and purpose-fitting than an average mass-produced item as a result of the profusion of amateur handicrafts of varying quality and inept imitation.

By the time the war started in 1914, the movement was in trouble and on the decline. Financially, its 1912 exhibition had been a complete failure. The Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, now run by an old guard, was turning away from manufacturer collaboration and commerce in favor of purist handwork. Meanwhile, designers in continental Europe were innovating in design and forming alliances with industry. Its refusal to serve a commercial function has been considered to represent a turning point in its trajectory. People who were involved in the Arts and Crafts movement were viewed as radical designers who tried to reform the modern movement but ultimately failed and were replaced by it.

Arts and Crafts Architecture

The Arts and Crafts movement had its greatest and longest-lasting impact on architecture, and many of its leaders had backgrounds as architects. Philip Webb’s 1859 design for Morris of Red House in Bexleyheath, London, is regarded as a prime example of the early Arts and Crafts architecture style. It has substantial, well-proportioned forms, a steep roof, large porches, brick fireplaces, pointed window arches, and wooden fixtures. Webb eschewed traditional revivals of historical forms centered around big and grand buildings in favor of British vernacular architecture, presenting the texture of everyday materials such as tiles and stone by means of an asymmetrical and charming architectural composition.

Bedford Park, a London neighborhood developed primarily in the 1880s and 1890s, features around 360 Arts and Crafts style residences and was once very popular. The very first Arts and Crafts homes were built in the vernacular design made popular by Raymond Unwin and Barry Parker, and the community came to represent a simple way of life. Arts and Crafts Movement examples in architecture include Wightwick Manor in Wolverhampton, England, Blackwell in Lake District, England, Marston House in San Diego, California, and Edgar Wood Center in Manchester, England.

Garden Design

Gertrude Jekyll designed gardens using Arts and Crafts concepts. She collaborated with Sir Edwin Lutyens, the English architect, for whose projects she produced various landscapes and who developed her residence Munstead Wood in Surrey, near Godalming. Jekyll designed the gardens for the house of York architect Walter Brierley, Bishopsbarns. A gardener who had previously worked with Jekyll and Lutyens at Castle Drogo, George Dillistone, designed the garden for Brierley’s final project, Goddards in York.

The garden at Goddards featured a variety of characteristics that represented the house’s arts and crafts design, such as the placement of hedges that divided the garden into a number of outdoor rooms.

Art Education

The Arts and Crafts movement’s ideas were embraced in the late 1880s by the New Education Movement, which consisted of handicraft education in schools at Bedales and Abbotsholme, and his impact can be seen in Dartington Hall’s mid-century social experiments. Arts and crafts practitioners in the United Kingdom were critical of the government’s art education system, which was oriented on abstract design with little emphasis on practical skills. Concerns were raised in industrial and governmental spheres about the absence of craft training, and in 1884 a Royal Commission suggested that art education focus more on the compatibility of designs to the materials in which they were to be created.

The first institute to implement this move was the Birmingham School of Arts and Crafts, having “paved the way for integrating executed designs into the instruction of design and art across the country, working with the materials for which the designs were created instead of designing on paper”. Other local authority schools started to adopt more real-world craft training, and by the 1890s, representatives of the Art Workers Guild were spreading the Arts and Crafts styles and concepts throughout the country. Crane sought to restructure the Royal College of Art in 1898, yet was ultimately rejected by the Board of Education due to bureaucracy and left after a year.

The development in the late 19th century of the Arts and Crafts movement in Britain signaled the start of a shift in society’s values of how things were manufactured. This was a response to both the negative impacts of industrialization and the decorative arts’ comparatively low status. The Arts and Crafts movement revolutionized the design and production of everything from houses to jewelry. Since 1840, Britain has recognized the negative consequences of machine-dominated manufacturing on both social circumstances and the standard of manufactured products. However, it wasn’t until the 1860s and 1870s that inventive approaches to design and architecture were advocated in the hopes of solving the problem.

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Did the Arts and Crafts Movement Get Its Name?

The movement was named after the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, which was an organization that was created in London in 1887. The movement was structured more by a set of objectives than a prescribed style. The Society’s main goal was to establish new relevance for decorative artists’ work. In 1888, the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society held its first annual exhibition, displaying Arts and Crafts movement examples of work that it thought would help enhance the intellectual and social importance of crafts.

What Defines the Arts and Crafts Style?

The movement marked a move away from industrialized manufacturing, and handcrafted items were more highly valued. They also felt that there should be no division of labor.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Arts and Crafts Movement – A Revolutionary Style of Design.” Art in Context. June 28, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/arts-and-crafts-movement/

Meyer, I. (2023, 28 June). Arts and Crafts Movement – A Revolutionary Style of Design. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/arts-and-crafts-movement/

Meyer, Isabella. “Arts and Crafts Movement – A Revolutionary Style of Design.” Art in Context, June 28, 2023. https://artincontext.org/arts-and-crafts-movement/.