Famous Greek Statues – 27 Iconic Sculptures of Antiquity

The ancient Greeks have earned a place in the history books for their complex mythologies, their revered philosophers, and legendary war heroes. Ancient Greek artifacts have revealed many details about the times during which these ancient Greek statues were created. In this article, we will explore the top 27 most famous Greek statues that you need to know. Keep reading for more about these ancient masterpieces!

Table of Contents

- 1 An Introduction to Greek Sculpture

- 2 The Top 27 Most Famous Greek Statues of All Time

- 2.1 The Lady of Auxerre (c. 650 – 625 BCE)

- 2.2 The Sacred Gate Dipylon Kouros (c. 560 BCE) by the Sacred Gate Sculptor

- 2.3 Kleobis and Biton (c. 580 BCE) by Polymedes

- 2.4 Moschophoros (c. 570 BCE)

- 2.5 Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE)

- 2.6 Dying Warrior (c. 505 – 500 BCE)

- 2.7 Leda and the Swan (c. 500 – 450 BCE) by Timotheus

- 2.8 Kritios Boy (c. 480 BCE) by Kritios

- 2.9 The Charioteer of Delphi (c. 470 BCE)

- 2.10 Zeus and Ganymede (c. 470 BCE) by Corinthian Workshop

- 2.11 Statue of Zeus at Olympia (c. 466 – 435 BCE) by Phidias

- 2.12 The Riace Bronzes (c. 460 BCE) by Myron and Alcamenes

- 2.13 The Artemision Bronze (c. 460 BCE)

- 2.14 Discobolus (c. 460 BCE) by Myron

- 2.15 The Marble Metopes of the Parthenon (c. 447 – 438 BCE) by Phidias

- 2.16 The Parthenon Marbles (c. 447 – 438 BCE) by Phidias

- 2.17 Athena Parthenos (c. 447 BCE) by Phidias

- 2.18 The Parthenon Frieze (c. 443 – 437 BCE) by Phidias

- 2.19 Doryphoros (c. 440 BCE) by Polykleitos

- 2.20 Hermes of Praxiteles (c. 400 BCE) by Praxiteles

- 2.21 Aphrodite of Knidos (350 BCE) by Praxiteles

- 2.22 Farnese Hercules (c. 350 – 300 BCE) by Lysippos

- 2.23 Diana of Versailles (c. 325 BCE) by Leochares

- 2.24 The Dying Gaul (c. 230 – 220 BCE) by Epigonus

- 2.25 The Winged Nike of Samothrace (c. 200 BCE) by Pythocritos

- 2.26 Laocoön and His Sons (c. 200 BCE) by Polydorus, Athenodoros, and Alexander

- 2.27 Venus de Milo (c. 130 – 100 BCE) by Alexandros

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

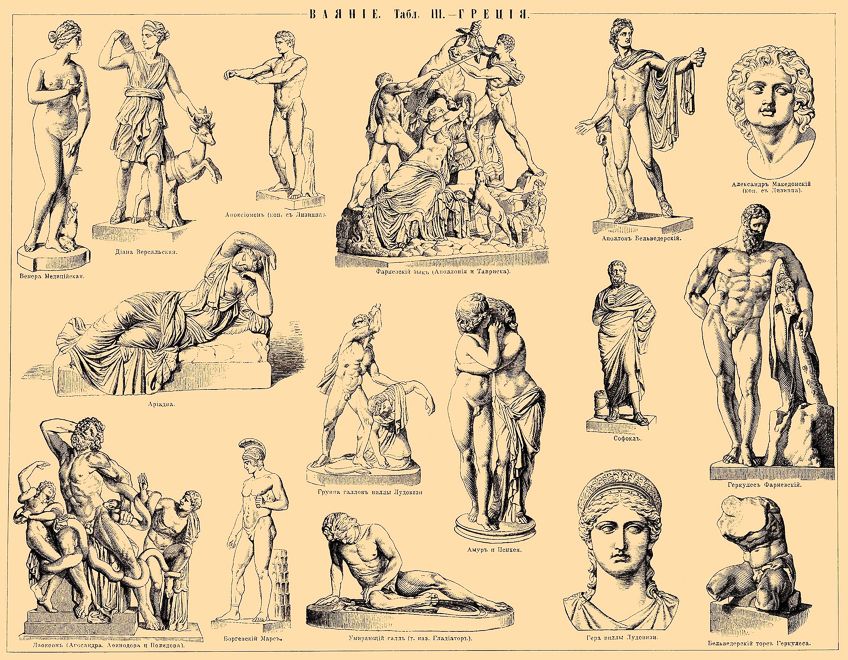

An Introduction to Greek Sculpture

Ancient Greek statues are generally accepted to have resulted from the influence of a mixture of Syrian, Minoan, Egyptian, Persian, and Mycenaean cultures. These cultures can be traced further back to Indo-European tribes that migrated from Northern regions of the Black Sea. Techniques such as bronze-casting and stone-carving were passed down to the Greek sculptors by the Syrians and the Egyptians.

The development of ancient Greek statues itself is divided into three chronological periods. From 650 BCE until 500 BCE, Greek sculptors first began developing monumental sculptures made from marble. This period was known as the Archaic period.

Ancient Greek artifacts reveal that most Greek sculptures were created primarily for religious functions in the Archaic and Classical periods.

From 500 BCE until 323 BCE, Greek sculpture reached its creative pinnacle in what was known as the Classical period, which saw an increase in sculpture production. Finally, the Hellenistic period was one of the most renowned eras that lasted between 323 BCE and 27 BCE.

During the Hellenistic era, many Greek sculpture styles had spread throughout the Eastern Mediterranean.

Many Greek statues were crafted from materials such as marble, terracotta, bronze, and wood, which gave Greek sculptures their signature look and feel. Although bronze was only used in large capacity between 550 BCE and 500 BCE, around half of ancient Greek statues were made from it.

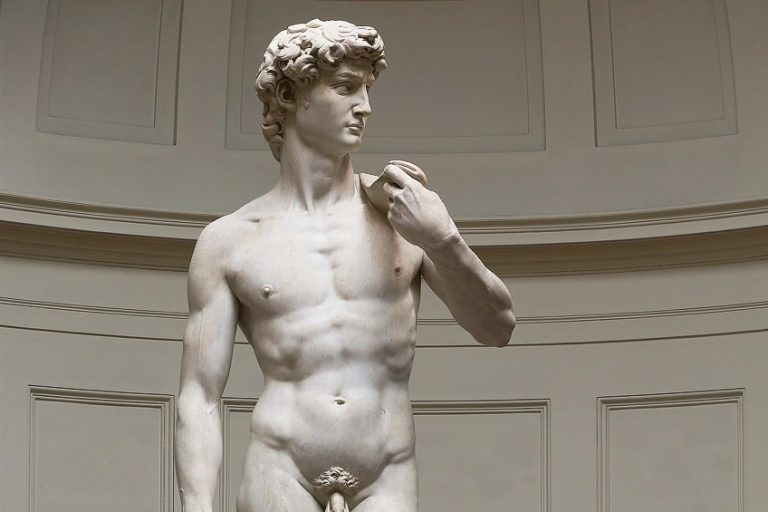

Ancient Greek statues are easily characterized by their realistic stance and accurate depictions of human anatomy.

Greek sculptors are also credited with developing the contrapposto stance, which involves the placement of figures in such a way that their form appears to rest on one foot while the other foot is portrayed as bent. Today, one can find many masterpieces of the ancient world that showcase the sculptural talents of Greek artists in institutions such as the Archaeological Museum of Olympia in Greece and the Louvre Museum in Paris. More information about the history of art in Greece can be found in our article about Greek art.

The Top 27 Most Famous Greek Statues of All Time

Ancient Greek art has left us with many gems from the past that show us the beauty and finesse of Greek sculpture and culture. From the works of famous sculptors such as Phidias and Myron to Callimachus and Kalamis, below, we will explore some of the most famous Greek statues from the golden era of Greek sculpture!

The Lady of Auxerre (c. 650 – 625 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 650 – 625 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone |

| Dimensions (cm) | 75 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

The Lady of Auxerre was found in a storage vault in the Museum of Auxerre and was discovered by a Louvre curator named Maxime Collignon in 1907. While no one knew how the statue came to be there, many scholars concur that The Lady of Auxerre represents Persephone, who was the daughter of the mythological being Demeter.

Others suggest that it could also represent a Greek woman statue known as a “kore” or maiden, which was created as an offering to Persephone. The male version of a kore is a “kouros” and these sculptures were most often used as grave markers.

All that remains of this statue and other sculptures of its era is its limestone surface, as any paint that once decorated ancient Greek sculptures have been lost to time. Minoan influence can be seen in her narrow waist and an Egyptian influence can be seen in the rigid representation of her hair.

The Sacred Gate Dipylon Kouros (c. 560 BCE) by the Sacred Gate Sculptor

| Artist Name | Sacred Gate sculptor |

| Date | c. 600 – 590 BCE |

| Medium | Naxian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 200.1 |

| Where It Is Housed | Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece |

This famous kouros was discovered in the ancient Kerameikos cemetery at a site known as the Sacred Gate in 2002. Unearthed by the German Archeological Institute, the cemetery was part of the potter’s corner of ancient Athens. The statue depicts a male figure that was used for marking graves and crafted from Naxian marble. Standing at just over two meters high, the Greek sculpture was found along with two lions made from marble, pillar fragments, and a sphinx.

Although it cannot be proven with certainty, some scholars have suggested that it could be the work of an unknown Dipylon sculptor, who was perhaps also a vase painter from Greece.

Although his name is not known, a similar kouros was previously found 40 meters away from the recent discovery in 1916. Another head of a sculpture, which is currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, bears similarities in dimension and design to both heads found in 2002 and 1916. It is known that the first two are the work of the Dipylon sculptor and so it is highly likely that this new discovery was another work of ancient Greek artifacts created by the resident Sacred Gate sculptor.

Kleobis and Biton (c. 580 BCE) by Polymedes

| Artist Name | Polymedes of Argos (6th century BC) |

| Date | c. 580 BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 216 |

| Where It Is Housed | Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece |

These ancient Greek statues were found in Delphi in 1893 but originally came from Argos. The famous Greek statues are nude and identically crafted from Parian marble. Inscribed on the base of the statues is the name of the sculptor, Polymedes of Argos. There are two different interpretations of who the statues are meant to represent but both of them are rooted in Greek mythology.

Besides the name of the sculptor, there was also another word inscribed on the base of these ancient Greek artifacts.

Archeologists were also able to make out the word fanakon on the base, which translates to the word “princes”. This term was usually used in reference to Pollux and Castor, who were the twin sons of the Greek God Zeus and who were worshipped widely in Argos at the time. The other mythological narrative involves the offspring of a priestess who worked for Hera, a goddess of Delphi. This priestess was known as Cydippe and her sons were two human brothers named Kleobis and Biton.

Moschophoros (c. 570 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 560 BCE |

| Medium | Limestone |

| Dimensions (cm) | 165 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece |

This ancient Greek sculpture is also known as The Calf Bearer in English and was created in the Archaic period. It had been discovered in 1864 in the Acropolis of Athens and was reconstructed from fragments that were found during the Persian invasion, therefore, it is not in the best condition since both legs are missing from the knees down. Other missing features include the statue’s left thigh, genitals, and hands.

Although found in 1864, the base was only discovered three years later.

The statue was made from limestone and stands at 165 cm tall. An inscription on the base indicates that the statue was dedicated to the goddess of wisdom, Athena by a person identified as Rhombas. It has been suggested that the statue was made in the likeness of the patron who commissioned it and was most likely a prominent figure in the Attican region.

Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 530 BCE |

| Medium | White marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 118 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece |

This Greek woman statue is one of the most famous Greek statues of the Archaic period. Based on traces found on the marble, it was originally painted in bright colors and was sculpted from white marble. The 118 cm-high statue was found in an excavation site in 1886 near the Athenian Acropolis, in three separate pieces. The statue was named after the fabric depicted, which was used for making shawls and robes called peplos. At the time of its creation, the fabric was no longer part of modern fashion.

Although it is uncertain who among the Greek sculptors originally created it, some scholars believe that it could be the work of the Rampin Master, who created another famous sculpture from the Archaic period known as “The Rampin Rider”.

Historians suggest that the stance of the statue depicts a goddess and not a mortal human. Normal kore postures included depicting one leg forward, with her left hand holding the skirt and the right hand holding an offering. There are two lines with 35 holes around her head, indicating that the statue may have included a crown at some stage.

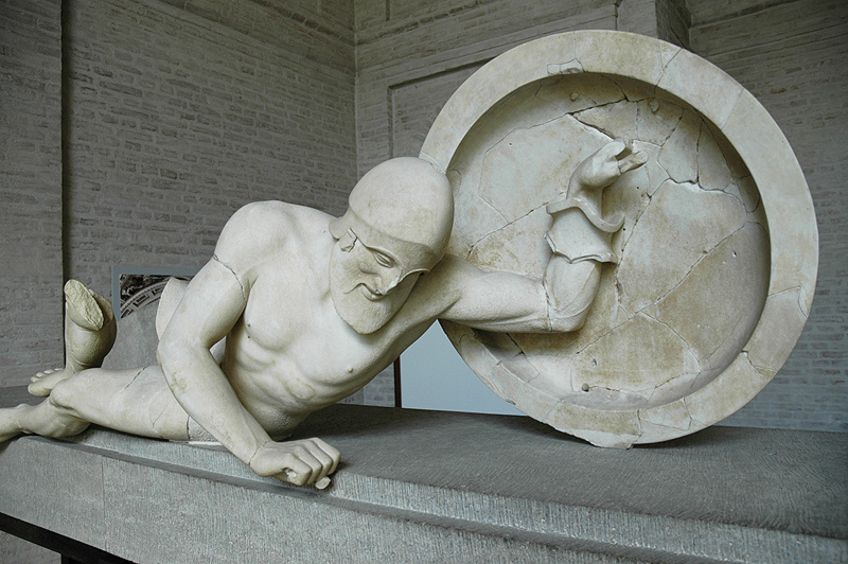

Dying Warrior (c. 505 – 500 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 505 – 500 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 185.9 (l) |

| Where It Is Housed | Glyptothek Museum, Munich, Germany |

Built as a dedication to the goddess Aphaia, the temple of Aphaia was situated on the island of Aegina within a sanctuary. The current temple was built on the site of two previous temples that had been destroyed through the ages. Ancient Greek statues were removed from the western and eastern pediments of the temple and were shipped overseas. Once there, they were sold to Ludwig I of Hanover. The Greek sculpture is thought to portray Laomedon, a fallen Trojan hero.

It was common to depict figures who had fallen in battle, as the Greeks believed that if one fell in battle, then one became immortal.

It was seen as an honor to die in such a way, and Greek sculptors depicted these men as courageous heroes. Even though the back parts of the marble statues were not visible to the human eye, they had been just as exquisitely polished as the rest of the sculpture, as nothing escaped the eyes of the gods. This beautifully crafted sculpture was part of a series from the Archaic period that would end up in the Glyptothek in Munich. They have since been shown to have had a significant influence on the architecture and art of Munich.

Leda and the Swan (c. 500 – 450 BCE) by Timotheus

| Artist Name | Timotheus (375 – 350 B.C) |

| Date | c. 500 – 450 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 132 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, California, United States |

The Greek sculpture Leda and the Swan was created by the sculptor Timotheus sometime between 500 and 450 BCE. Today more than 20 Roman replicas exist, attesting to how popular the theme was in the Roman world. It was based on the Greek mythological story of how Zeus tried to seduce the queen of Sparta, Leda, by turning himself into a swan.

The most well-known Roman version of the original Greek sculpture was found in Rome in 1775 and was believed to have been sculpted in the first century.

Just like the original, the clothing both reveals and conceals the naked body of the statue, as it was created in a time when full nudity in statues was considered acceptable. The contrasting use of cloth, which is heavily folded in some sections and transparently clings to the body in other places, are characteristics of the work of Timotheus. After it was discovered, the statue was restored in the 18th century with amendments to the swan’s head, cloak, and Leda’s arms.

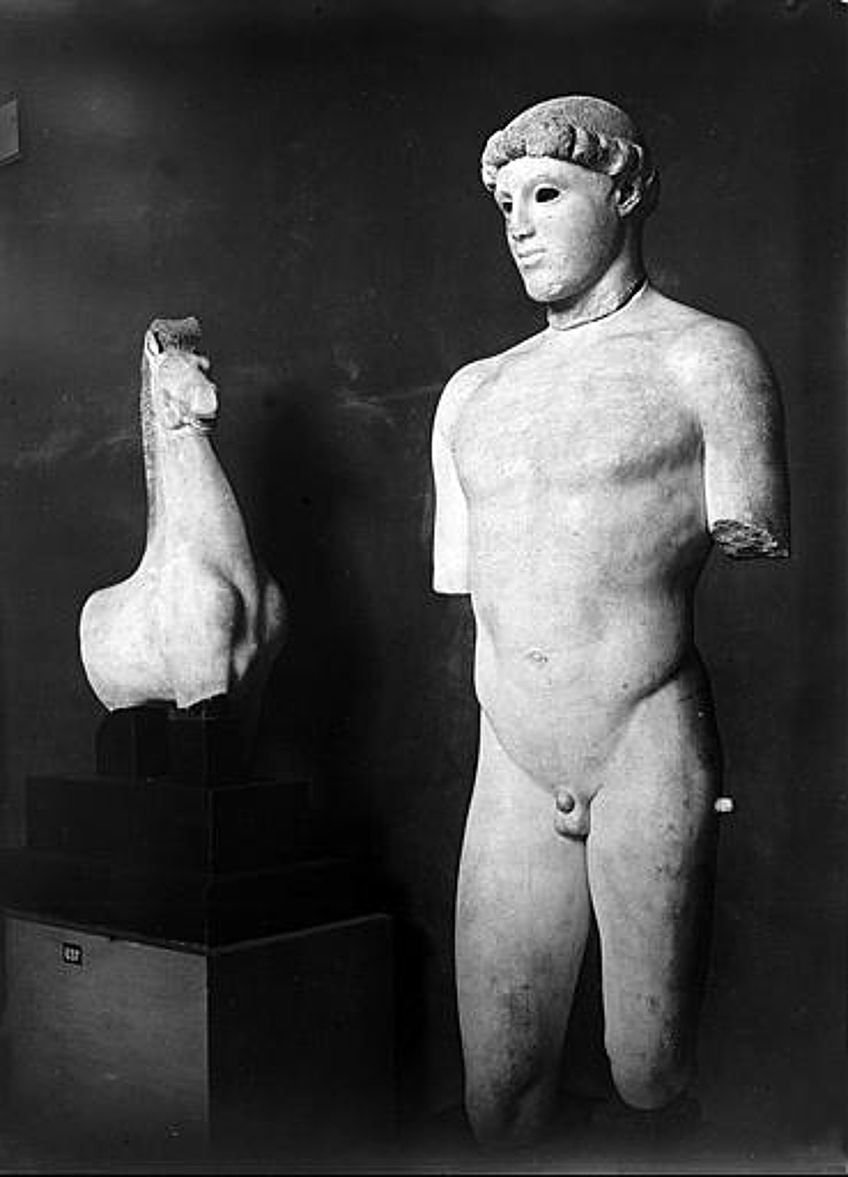

Kritios Boy (c. 480 BCE) by Kritios

| Artist Name | Kritios (early 5th century BCE) |

| Date | c. 480 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 86 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece |

The Kritios Boy is also known as the Ephebe Youth and was discovered in 1866 during an excavation of the Acropolis in Athens. It was headless at the time and the head was only found 23 years after the body was unearthed. The Greek sculpture is less than life-sized and was made from marble. It was named after the sculptor Kritios, who was a prominent figure of the period.

“The Kritios Boy” has been cited as a prime example of ancient Greek statues that were created during the shift from the Archaic period to the early Classical period. This was indicated by the posture, which became more natural and less rigid.

The Kritios Boy was sculpted in the contrapposto stance, with the weight bearing down on a single leg and the other bent in a natural manner. It was a very early example of the development and understanding of human anatomy by Greek sculptors, and an attempt to portray the human body accurately and realistically.

The Charioteer of Delphi (c. 470 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 470 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 180 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Delphi Archaeological Museum, Greece |

This bronze sculpture was found in the sanctuary of Apollo in Delphi in 1896 and is one of the most well-preserved statues from the Delphi region. Also known as The Reign Holder, it is widely accepted that it was created to commemorate of the victory of Polyzalus at the Pythian Games. The Charioteer of Delphi was originally part of a group of sculpture but the others were moved and melted for resale. Luckily, this sculpture managed to escape after it was trapped under a rockfall.

The other sculptures that were originally part of the group included four horses, two grooms, and a chariot.

It is unknown who made the sculptures for sure but it has been attributed to several Greek sculptors, including Pythagoras and Calamis. Despite its Sicilian theme, it is believed the sculpture was cast in Athens due to certain stylistic observations. Scholars pointed out several stylistic similarities with other statues from Athens such as the Piraeus Apollo (c. 530 BCE). The bronze statue also attained its distinctive green tinge from its many years of exposure to a humid and enclosed space.

Zeus and Ganymede (c. 470 BCE) by Corinthian Workshop

| Artist Name | Corinthian workshop |

| Date | c. 470 BCE |

| Medium | Terracotta |

| Dimensions (cm) | 310 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Olympia Archaeological Museum, Greece |

This terracotta Greek sculpture is from the late Archaic period and depicts Zeus carrying Ganymede to Mount Olympus. It was originally used as an acroterion for one of the Olympian treasuries and is nearly life-sized, which was unusual considering the medium. The sculpture has since been attributed to a Corinthian workshop and was created in the period of transition between the Archaic and Classical eras.

The sculpture was found in fragments during different periods of excavation, with the first parts being discovered in 1878 in the western and eastern areas of the Olympic stadium.

More fragments were discovered at the same site during various excavations until 1938. The sculpture is far from complete but has been reconstructed in its best form using its many fragments. Today, the sculpture can be found at the Olympia Archeological Museum, as the earliest example of Greek art in which the subject’s eyes do not simply stare forward, but was executed in an expressive and realistic manner.

Statue of Zeus at Olympia (c. 466 – 435 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist Name | Phidias (480 BCE) |

| Date | c. 466 – 435 BCE |

| Medium | Gold, bronze, ivory, and ebony |

| Dimensions (cm) | 1240 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Temple of Zeus, Archaeological site of Olympia, Greece |

Erected at the Temple of Zeus, this massive sculpture of the Greek God Zeus once stood at a towering height of over 12 meters and was created by renowned sculptor, Phidias. Phidias began construction on the sculpture around 466 BCE and only completed it by 435 BCE. The ornate decoration of the work and its opulent materials is what made it a legendary statue.

Sculpted from bronze, ebony, ivory, and gold, the sculpture was recognized as a chryselephantine sculpture, of which involved the use of wooden framework that was decked with gold panels. Before the turn of the 5th century, the Statue of Zeus at Olympia was believed to have been destroyed or lost, however, it remains a lost work of art that is also recognized as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World.

The Riace Bronzes (c. 460 BCE) by Myron and Alcamenes

| Artist Name | Myron (c. . 480 – 440 BCE) and Alcamenes (c. 5th century BCE) |

| Date | c. 460 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 198 x 199 |

| Where It Is Housed | Museum of Reggio Calabria, Reggio Calabria, Italy |

The Riace Bronzes were discovered by accident in 1972, when an amateur scuba diver named Stefano Mariottini was out snorkeling off the shore of Riace in Calabria when he spotted what appeared to be a human arm sticking jotting out of the seabed. After contacting the police and concluding that the limb was not human, archeologists arrived on scene to uncover the famous bronze Greek statues.

The statues have been labeled simply “Statue A” and “Statue B”, and differ in size by a centimeter.

Based on their posture, the figures once held spears in their hands. Although it is uncertain exactly who created them, it has been suggested that they were created by different Greek sculptors, with Myron being a likely candidate for Statue A and Alcamenes being the possible sculptor of Statue B. Despite the time of their discovery, the statues were not exhibited until 1981 in Rome and Florence, where they drew crowds of over a million people in just a year.

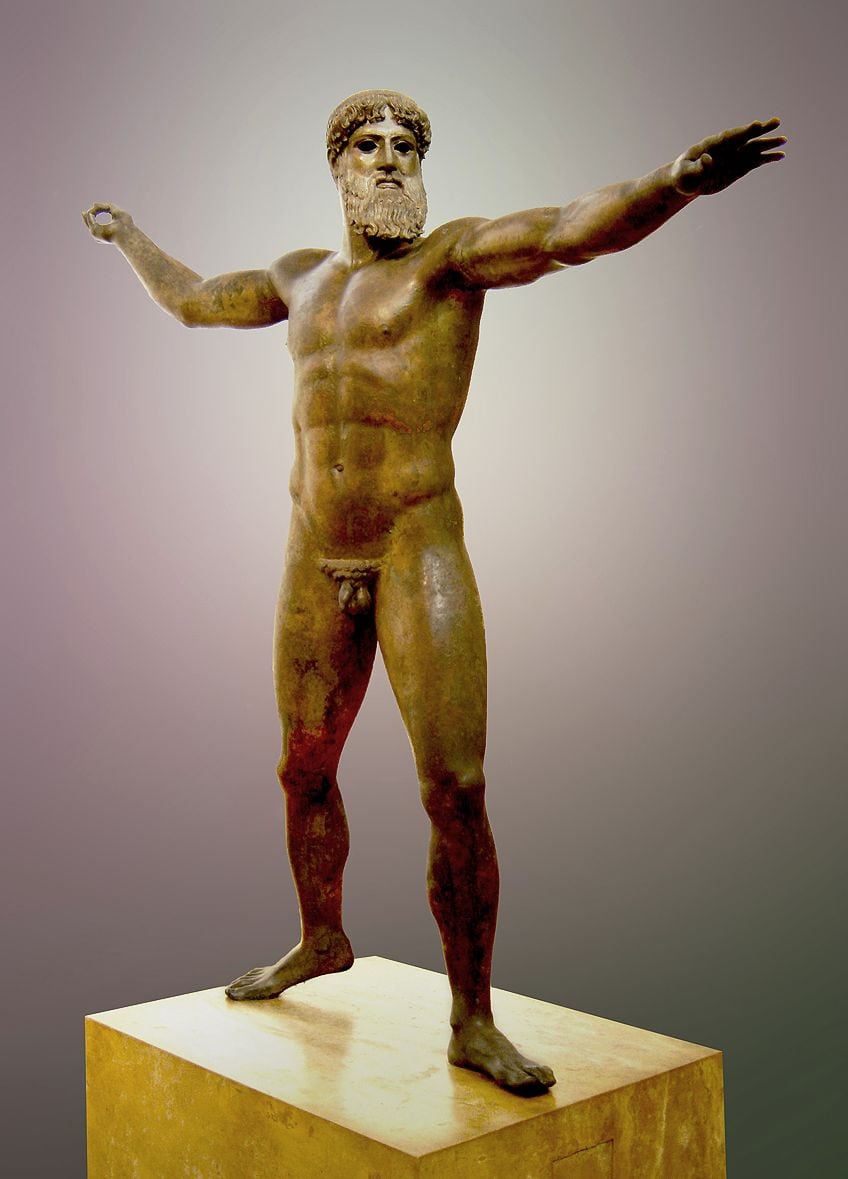

The Artemision Bronze (c. 460 BCE)

| Artist Name | Unknown |

| Date | c. 460 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze |

| Dimensions (cm) | 209 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece |

During the excavation of a Roman shipwreck between 1926 and 1928, a bronze statue was lifted from the sea in two pieces just off the Cape of Artemision. It is said to portray one of the Greek Gods, Poseidon or Zeus. Whatever he was once holding was lost to the ocean forever and would have helped in discovering the identity of the statue since Poseidon would have been depicted with a trident and Zeus with a bolt of lightning.

The eyes of the sculpture were also believed to have been inset with pupils sculpted from bone but are now empty. The eyebrows were originally lined with silver and the nipples and lips would have been lined with copper. Due to the origins of the sculpture, it is uncertain who sculpted this masterpiece, however, scholars have suggested a range of artists such as Myron, Kalamis, or Onatas.

The hypothesis that it represents Poseidon has been a subject of much doubt since the trident would have obscured the figure’s face, and would have been an uncommon posture for representing Poseidon.

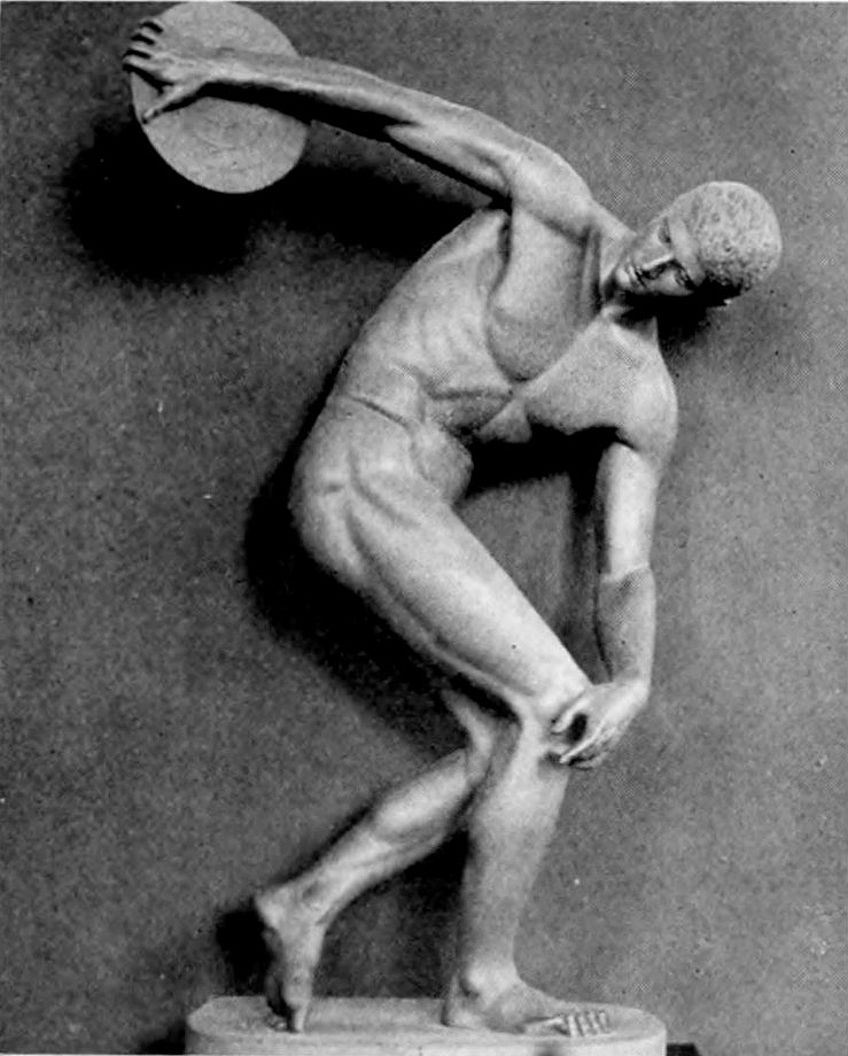

Discobolus (c. 460 BCE) by Myron

| Artist Name | Myron (5th century BCE) |

| Date | c. 460 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze (original) and marble (copies) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 193 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | National Museum of Rome, Rome, Italy |

Today there are many Roman copies that remain of the original bronze statue of Discobulus. The statue, also known as the Discus Thrower, is believed to have been sculpted by Myron of Eleutherae. Eleutherae was a famous sculptor from Athens known for his bronze representations of athletes. Created around 460 BCE, there have been many reproductions of the famous discus thrower. The first sculpture was unearthed at the property of the Massino family in 1781. Made in the first century, the Palombara Discobolus was discovered at the Villa Palombara, which was situated on Esquiline Hill.

After it was restored, the sculpture was installed at various sites, including the Palazzo Lancellotti until it was bought by Hitler in 1938. The sculpture was sold to Hitler by the Minister of Foreign Affairs in Italy, Galeazzo Ciano, for five million lire.

The sculpture was then sent by train to Germany, where it was displayed at the Glyptothek in Munich. In 1948 the sculpture was returned to Italy where it has been on display ever since at the National Museum of Rome. Another copy was found in 1770 at Hadrien’s wall, which was purchased by Thomas Jenkins, an English art dealer in an auction in 1792. In 1805, it was bought by Charles Townly for the British Museum for four hundred pounds sterling.

The Marble Metopes of the Parthenon (c. 447 – 438 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist Name | Phidias (480 BCE) |

| Date | c. 447 – 438 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 120 x 125 |

| Where It Is Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

The marble Metopes of the Parthenon originally were 92 panels that were created to enhance and beautify the Parthenon’s exterior and are well-known examples of Greek high-relief sculptures from the classic period. The metopes portrayed various scenes from Greek mythology and symbolized victory over chaos and passion by reason. On the Eastern and Western walls were fourteen metopes, and on the Southern and Northern walls were thirty-two metopes.

The metopes on the Eastern wall were situated above the Parthenon’s main entrance and depicts the last stages of the battle fought between Olympian gods and the giants.

Images such as Neptune and his trident, Hera riding a chariot, and a depiction of Zeus can be seen. On the Southern wall’s metopes is the depiction of the battle of the Aeolian tribe known as the Lapiths, against the mythical creatures known as Centaurs. The Northern wall’s metopes portray the battle between the Trojans and the Greeks, commonly known as “The Sack of Troy”. Only 14 of the original 32 panels survived after a cannonball hit the Parthenon in 1687.

The Parthenon Marbles (c. 447 – 438 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist Name | Phidias (480 BCE) |

| Date | c. 447 – 438 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 123 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom |

The Parthenon Frieze‘s east pediment depicted the birth of Athena from the head of Zeus, who was her father. The figures, which represented a part of the scene now lost, was Athena was moving away from Zeus as an armed and fully grown women.

To accommodate the sloping curve of the architectural moldings, the posture of each figure varied accordingly.

The Parthenon Marbles statues are noted for their realistic depiction of human anatomy mixed with the representation of drapery in a complex yet harmonious manner. The figure on the left can be seen on the verge of standing up, with her right leg tucked in to help lever herself up. A figure to the right can be seen reclining in the lap of another figure. A few of the mythological beings have been identified as Aphrodite, Dione, and Hestia, who was the goddess of the home.

Athena Parthenos (c. 447 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist Name | Phidias (480 BCE) |

| Date | c. 447 BCE |

| Medium | Ivory and gold |

| Dimensions (cm) | 1200 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Athens, Greece |

This ancient Greek sculpture depicted the Greek goddess Athena and was sculpted from ivory and gold by Phidias. Athena Parthenos was originally located in the Parthenon in Athens as the focal point of the Parthenon, and although greatly admired in its time, it has since been lost to history. Many replicas have been created since then, as well as other works that were inspired by the description of this statue of Athena, the goddess of war and wisdom.

It was considered an artwork that epitomized the image of Athena and was regarded as the pinnacle of Phidias’ achievements.

The sculpture experienced a series of events that would cause great damage to the statue, including an instance when the tyrant Lachares took the sheets of gold off the sculpture to pay his soldiers in 296 BCE. It was further damaged in 165 BCE in a huge fire but was later repaired. There were accounts of its appearance in the 10th century in Constantinople. Today, there are ancient replicas that can be viewed, including the 3rd-century Varvakeion Athena, which is housed in the National Archeological Museum of Athens.

The Parthenon Frieze (c. 443 – 437 BCE) by Phidias

| Artist Name | Phidias (480 BCE) |

| Date | c. 443 – 437 BCE |

| Medium | Pentelic marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 16000 (original); 12800 (h) (surviving) x 5.6 |

| Where It Is Housed | The British Museum, London, United Kingdom and the Acropolis Museum, Athens, Greece |

Constructed under the management of Phidias, the famous Parthenon Frieze once towered over the Parthenon at a staggering 160 meters. The high-relief sculpture was carved from Pentelic marble on the naos section of the building and today is admired only through 80% of its remains, which lie in the British Museum and the Acropolis Museum in Athens. The frieze encompasses many unique compositions, from the Elgin Marbles to the Pediments of the Parthenon. The entire composition includes 378 figures and projects outwards at 5.6 cm.

One of the burning questions around the piece is whether it was carved “in situ” or not since the marble was transported from Mount Pentelicus, a quarry that was 19 kilometers away!

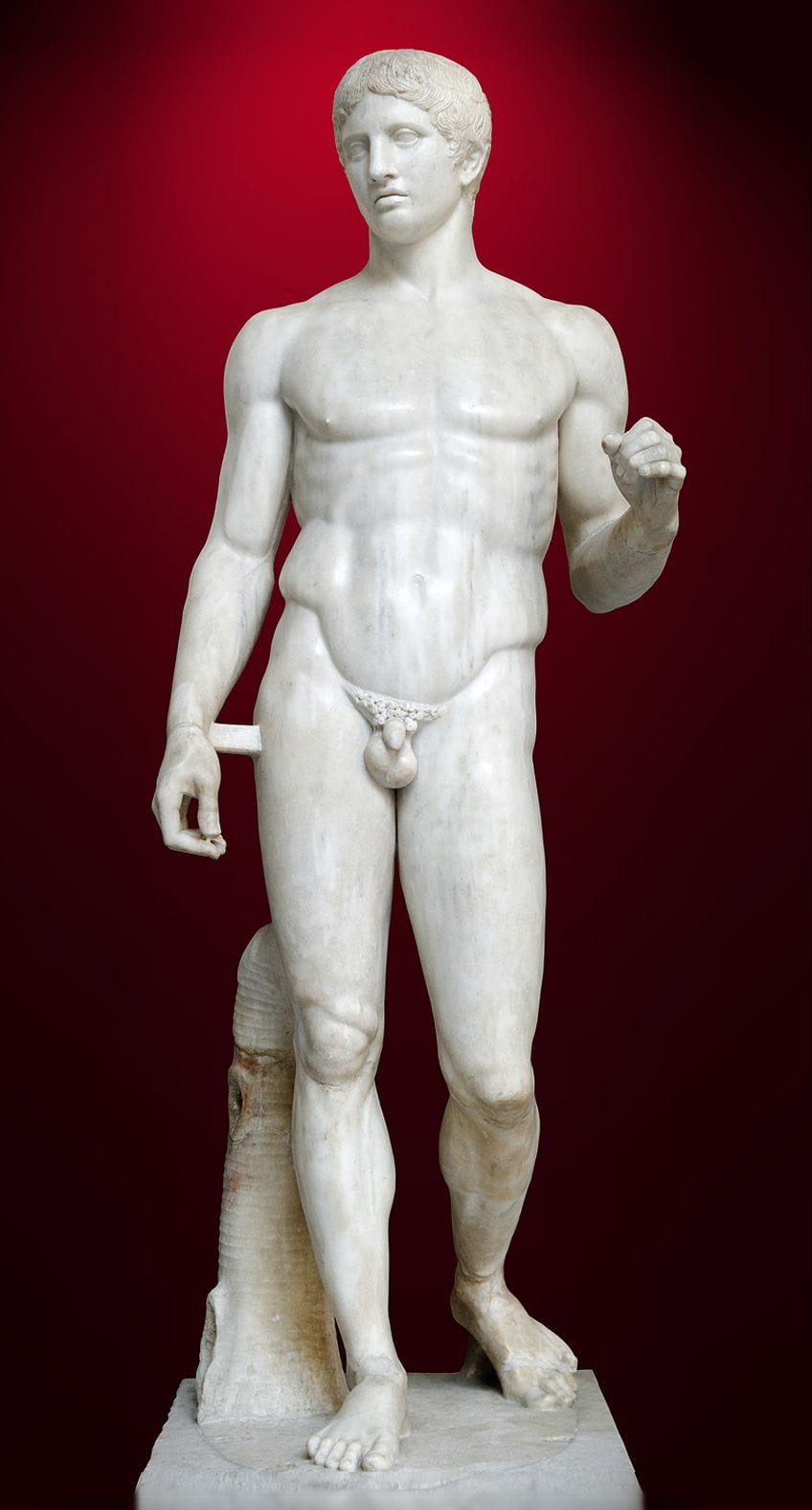

Doryphoros (c. 440 BCE) by Polykleitos

| Artist Name | Polykleitos (450 – 420 BCE) |

| Date | c. 440 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze (original) and marble (copies) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 212 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Naples National Archeological Museum, Naples, Italy |

Doryphoros is considered to be one of the most well-known sculptures from the period of classic antiquity. It is also known as the “spear-bearer” and originally had a spear positioned over the left shoulder of the sculpture. Due to many marble copies made by Roman sculptures, the sculpture is widely known today. The original sculpture was crafted in bronze by Polykleitos around 440 BCE.

Polykleitos sculpted the work to help demonstrate his written treatise on what he considered to be the “rules and measures” for the perfectly proportioned human frame.

The marble copy that exists today was discovered in Pompeii and dates to around 120 BCE. The original sculpture, as well as the treatise, have been lost to time. Polykleitos was highly interested in the notion of ideal proportions and had even created mathematical equations to help map out the ideal representation of human anatomy. His sculptures were said to achieve a delicate balance of appearing both relaxed in their stance while maintaining the correct muscular tension.

Hermes of Praxiteles (c. 400 BCE) by Praxiteles

| Artist Name | Praxiteles (330 BCE) |

| Date | c. 400 BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 200.12 |

| Where It Is Housed | Archeological Museum of Olympia, Greece |

Hermes of Praxiteles was rediscovered in 1877 during excavations at the Temple of Hera in Olympia. The sculpture stands at just over two meters tall and was sculpted from Parian marble. It has been controversially attributed to Praxiteles based on the remarks of Pausanias, a Greek traveler and historian from the 2nd century. Despite the uncertainty of its attribution, it is often cited as a definitive example of the Praxitelean style. As one of the most famous sculptures of the century, the statue is also recognized as Hermes and the infant Dionysus, the latter deity who is seen held in the arm of Hermes.

The doubt around its attribution to Praxiteles was based on the fact that most of his famous Greek statues were replicated by other Greek sculptors, whereas no replicas have been found dating from that period.

Towards the end of the 3rd century CE, a huge earthquake hit Olympia and the sculpture was buried under tons of rubble. Various archaeological expeditions were undertaken at the Olympia site, the most famous being the French expedition in 1829. It wasn’t until the German expedition led by Ernst Curtius in 1877, that the statue was unearthed once again. In May 1877, the torso, head, left arm, and legs were uncovered in the Temple of Hera. Due to the layers of clay that coated it, the statue remained in a decent state of preservation. The rest of what is displayed today was discovered over the course of six additional excavations.

Aphrodite of Knidos (350 BCE) by Praxiteles

| Artist Name | Praxiteles (330 BCE) |

| Date | c. 350 BCE |

| Medium | Marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 205 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Vatican Museum, Vatican City |

This Greek woman statue depicted the goddess Aphrodite and was created in the 4th century BCE by Praxiteles. It is highly significant in the Greek history of sculpture, as it was one of the first to portray the naked feminine form in a life-sized representation. Before this moment, Greek was largely dominated by male figures. In this sculpture, Aphrodite was portrayed nude and reaching for a towel, while covering her pubis, thereby exposing her breasts.

Based on the written texts of Pliny, Praxiteles was commissioned by the inhabitants of the Kos island to create a cult status for a temple dedicated to Aphrodite.

He created two versions, one without clothing and one that was clothed. The people instantly rejected the naked statue and took the clothed version. The naked version was bought by the people of the ancient city of Knidos. The original statue unfortunately no longer exists, but there are several Roman replicas that still exist. The replica that has been considered to be the most faithful replication of the original, is the Colonna Venus, which is a Roman copy that is now housed at Museo Pio-Clementino.

Farnese Hercules (c. 350 – 300 BCE) by Lysippos

| Artist Name | Lysippos (390 – 300 BCE) and Glykon (c. 200 – 250 CE) |

| Date | c. 350 – 300 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze (original) and marble (copy) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 317 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy |

This ancient Greek sculpture depicts the Greek hero Hercules and was most likely a larger replica of the bronze sculpture that was originally created by Lysippos. It is the most well-known copy that was sculpted by a Greek sculptor known as Glykon. The large marble statue stands at 317 cm tall while the original sculpture by Lysippos had survived for around one and a half centuries before the Crusaders melted it down during the Sack of Constantinople in 1205.

The copy by Glykon was found in 1546 and was created for the Baths of Caracalla in Rome. This sculpture of Hercules is one of the most well-known sculptures of antiquity.

There are also other copies known to be in existence, one of which now resides at the Louvre Museum and is a bronze Late Classical Greek period rendition of the famous Greek statue. A smaller marble copy has also been found and is currently housed at the Museum of the Ancient Agora in Athens. All versions depict a weary and muscular Hercules leaning against his club. The pelt of a lion is draped over the club, suggesting that this represents the myth about Hercules having to kill a Nemean lion as his first task.

Diana of Versailles (c. 325 BCE) by Leochares

| Artist Name | Leochares (4th century BCE) |

| Date | c. 325 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze (original) and marble (copy) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 201 |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

This sculpture is a Roman marble copy of the lost bronze original, which depicted the Greek goddess Artemis with a deer and was attributed to Leochares from around 325 BCE. Diana is a Roman goddess, who was portrayed in the middle of a hunting scene, drawing an arrow with which to pursue her prey. The sculpture was given to Henry II of France by Pope Paul IV in 1556.

The replica is thought to have been discovered in Italy, with suggestions of the original site being Hadrian’s Villa at Tibur or the Temple of Diana.

Although it is occasionally confused with the other Artemis statue, which is situated at the Temple of Ephesus, the Diana of Versailles is considered a masterpiece among other sculptures that were exported from Italy. The original bronze sculpture by Leochares was commonly known as Artemis with a Hind. Other replicas of the Greek original have been discovered in Algeria, Turkey, and Libya.

The Dying Gaul (c. 230 – 220 BCE) by Epigonus

| Artist Name | Epigonus (Greek) (c. 3rd century BCE) and Unknown Roman sculptor |

| Date | c. 230 – 220 BCE (original) and 100 – 200 BCE (Roman copy) |

| Medium | Bronze (original) and marble (copy) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 75 x 114 |

| Where It Is Housed | Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy |

The Dying Gaul is a famous Roman marble copy of an original Greek sculpture that was created in the Hellenistic period. The sculpture is a life-sized depiction of a Gallic warrior, who appears to take his last breaths after a strenuous battle. The famous Greek sculpture was copied between 100 and 200 BCE by a Roman sculptor, which remains on display at the Capitoline Museums in Rome.

The Winged Nike of Samothrace (c. 200 BCE) by Pythocritos

| Artist Name | Pythocritos (c. 210 – 165 BCE) |

| Date | c. 200 BCE |

| Medium | Thasian and Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 200.4 |

| Where It Is Housed | Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

Also known as Nike of Samothrace, the Winged Victory of Samothrace is a celebrated marble sculpture from the Hellenistic period is a depiction of the Greek goddess of victory. It has been displayed at the Louvre Museum since 1884 and has been hailed as one of the greatest sculptures in the world. Created in the 2nd century BCE, this Hellenistic masterpiece is one of the very few examples of famous Greek statues that are not Roman copies, but the original sculpture itself. The right-wing of the statue, however, is not the original wing and was added later by mirroring the left-wing. The statue is 2.44 meters tall and is made from Thasian and Parian marble.

The statue is said to represent the victory of a battle, of which is unknown to historians, and was sculpted by an artist named Pythocritos.

Some believe that it was created to commemorate the Battle of Salamis, which occurred in 306 BCE. Others believe that it was made in commemoration of the Battle of Actium, which occurred in 31 BCE. The prevailing theory for much of the 20th century was that it was a Rhodian monument with recent studies casting doubt over its proposed date since the surrounding debris of where the sculpture was discovered dated to a different period.

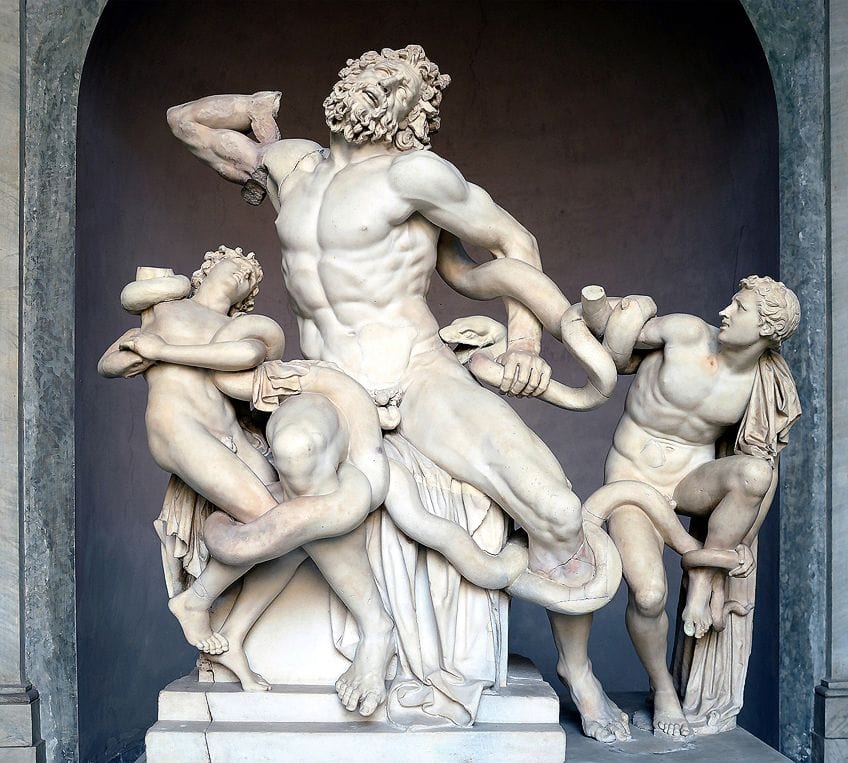

Laocoön and His Sons (c. 200 BCE) by Polydorus, Athenodoros, and Alexander

| Artist Name | Polydorus, Athenodoros, and Alexander (c. 3rd century BCE) |

| Date | c. 200 BCE |

| Medium | Bronze (original) and marble (copy) |

| Dimensions (cm) | 208 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | Vatican Museum, Vatican City |

Displayed at the Vatican Museum since its excavation in Rome in 1506, Laocoön and His Sons is one of the most well-known ancient sculptures of all time. It depicts the Trojan priest and his sons Thymbraeus and Antiphates facing a vicious attack from sea serpents. It has been described as the prototypical representation of human suffering in Western art and does not feature any of the redemptive qualities of the religious sculptures.

The pain of the Trojan priest can be seen in his agonized facial expression and contorted limbs.

The patron and exact date of creation are also not known, however, Pliny the Elder attributed the work to three Greek sculptors named Polydorus, Athenodoros, and Alexander, who were all from the island of Rhodes. Despite being in very good condition for such an ancient sculpture that had been excavated, it is still missing several pieces and analysis has revealed several restoration attempts through the ages.

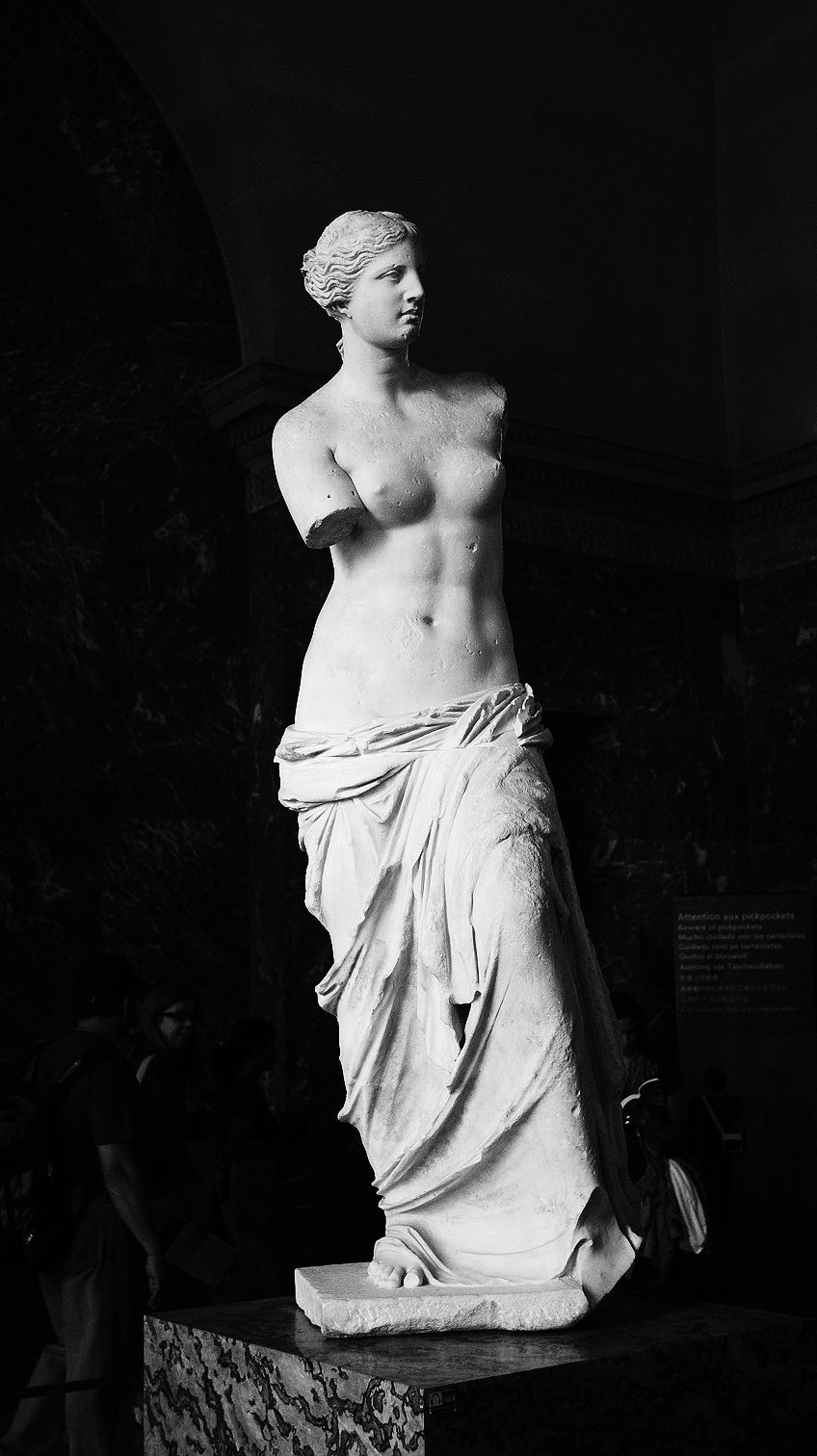

Venus de Milo (c. 130 – 100 BCE) by Alexandros

| Artist Name | Alexandros (356 – 323 BCE) |

| Date | c. 130 – 100 BCE |

| Medium | Parian marble |

| Dimensions (cm) | 204 (h) |

| Where It Is Housed | The Louvre Museum, Paris, France |

This ancient Greek sculpture was created during the Hellenistic period and it depicts the Greek Goddess Aphrodite or Venus. It was discovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Milos and has since been on display in the Louvre Museum in Paris. It was created sometime between 130 and 100 BCE and is considered one of the most recognizable Greek statues of all time. It stands 204 cm tall and was made from Parian marble.

Originally this famous sculpture was attributed to Praxiteles but is now widely believed to have been sculpted by Alexandros of Antioch due to an inscription on the plinth of the statue.

The statue is said to depict the Greek goddess of beauty and love known as Aphrodite. The inscription bears the Roman counterpart name for Aphrodite, which is Venus but the names are ultimately interchangeable. However, there is still debate as to who it actually represents as there are scholars who believe it is actually a depiction of Poseidon’s wife Amphitrite, who was revered in the island of Milos. Due to the misleading title, some people prefer to refer to the sculpture as the Aphrodite de Milos.

There are many examples of famous Greek sculptures for us to explore! As we have learned today, very few of these sculptures are the original versions that were sculpted in Greece itself, but those that remain are Roman replicas that were made by other sculptors. Luckily for us, the sculptors were experts at capturing the style and dimensions of the originals, allowing us to appreciate such precious Greek artifacts!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Most Famous Greek Statue?

Aphrodite of Milos (c. 130-100 BCE) is recognized as one of the most famous Greek statues in the world. The statue was created by Alexandros of Antioch and is also recognized as Venus de Milo.

What Were the Functions of Ancient Greek Statues?

Most Greek sculptures were primarily created for religious reasons throughout the Archaic and Classical periods. They were also created to celebrate certain victory battles and retell Greek mythological tales. Many Greek sculptors created votive statues for specific religious deities or mythological beings and were dedicated to various temples. A Greek man or Greek woman statue was often the human embodiment of a divine being and was sculpted in many various materials and sizes.

Why Do Original Greek Statues No Longer Exist?

Today, most of the versions we have of classic sculptures were made by Roman sculptors. This is due to many factors. In some places, natural factors such as earthquakes destroyed them. In other cases, they were ravaged by war. Sometimes, they were melted down and sold for their raw material value. Luckily, there are a few examples of Greek sculptures that still exist from that period, as well as many fine replicas that bear a strong resemblance to the original works.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Greek Statues – 27 Iconic Sculptures of Antiquity.” Art in Context. September 9, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-greek-statues/

Meyer, I. (2021, 9 September). Famous Greek Statues – 27 Iconic Sculptures of Antiquity. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-greek-statues/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Greek Statues – 27 Iconic Sculptures of Antiquity.” Art in Context, September 9, 2021. https://artincontext.org/famous-greek-statues/.