Archaic Greek Art – An Overview of the Greek Archaic Period

Following the Greek Dark Ages and replaced by the Classical era, the Greek Archaic period lasted from around 800 BC until the second Persian occupation of Greece in 480 BC. Greeks settled throughout the Mediterranean and Black Seas during the Archaic period in Greece, as far as Trapezus in the east, and Marseille in the west, and by the conclusion of the era, they were part of a Mediterranean trading network. The Greek archaic period started with a large rise in population and profound changes that made the Greek world completely unrecognizable by the end of the 8th century. Greek governance, economy, foreign relations, warfare, and Archaic Greek art all changed during the archaic period.

Table of Contents

Archaic Greek Art

The start of the Archaic period in Greece, in the seventh century B.C., sees a significant change in Archaic period art. In the seventh century, a more lifelike style exhibiting major influence from Egypt and the Near East replaces the abstract geometric patterns that were popular between roughly 1050 and 700 B.C.

Greek artists were motivated to engage in methods as diverse as ivory carving, gem cutting, jewelry making, and metallurgy by trading stations in the Nile Delta and the Levant, continuous Greek colonization in the east and west, and interaction with eastern artisans, particularly on Cyprus and Crete. Palmette and lotus arrangements, animal expeditions, and hybrid animals like griffins (part bird, half lion), sphinxes (part lady, part flying lion), and sirens were all introduced.

The roots of Archaic period art and Classical Greek art were laid by Greek painters quickly assimilating foreign styles and themes into fresh depictions of their own tales and traditions.

History of Archaic Period Art

The Greek world of the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. was made up of a slew of autonomous city-states known as poleis, which were divided by cliffs and the sea. Greek settlements spanned Asia Minor’s coast and the Aegean islands, as well as North Africa, mainland Greece, Sicily, and possibly Spain. The poleis on Asia Minor’s coast and nearby islands competed in the creation of sanctuaries with massive stone temples as their wealth and power expanded.

In the work of prominent poets like Sappho of Lesbos and Archilochos of Paros, lyric poetry, the dominant literary media of the day, reached new heights. Contact with rich towns like Lydia’s Sardis, which was governed by the mythical king Croesus in the sixth century B.C., impacted eastern Greek art. Large-scale marble sculptures were sculpted by sculptors in the Aegean islands, particularly on Samos and Naxos.

Fine jewelry was made by goldsmiths in Rhodes, while armor and plaques were made by bronzeworkers on Crete with magnificent reliefs.

Corinth, Sparta, and Athens, among mainland Greece’s most important creative hubs, all showed substantial regional variance. Sparta and its Lakonian neighbors created exceptional ivory sculptures and unusual bronzes. Corinthian artisans developed a silhouetted figure style with tapestry-like designs of miniature plant and animal themes. The vase artists of Athens, on the other hand, preferred to depict legendary situations.

Despite regional differences in dialect, the Greek language was a key uniting element throughout Greece. Additionally, Greek-speaking people gathered at the important Panhellenic sanctuaries on mainland Greece, such as Delphi and Olympia for celebrations and games.

Many artworks from Greece’s western and eastern areas were dedicated to these shrines. Greek painters became increasingly lifelike in their depictions of the human form throughout the sixth century B.C.

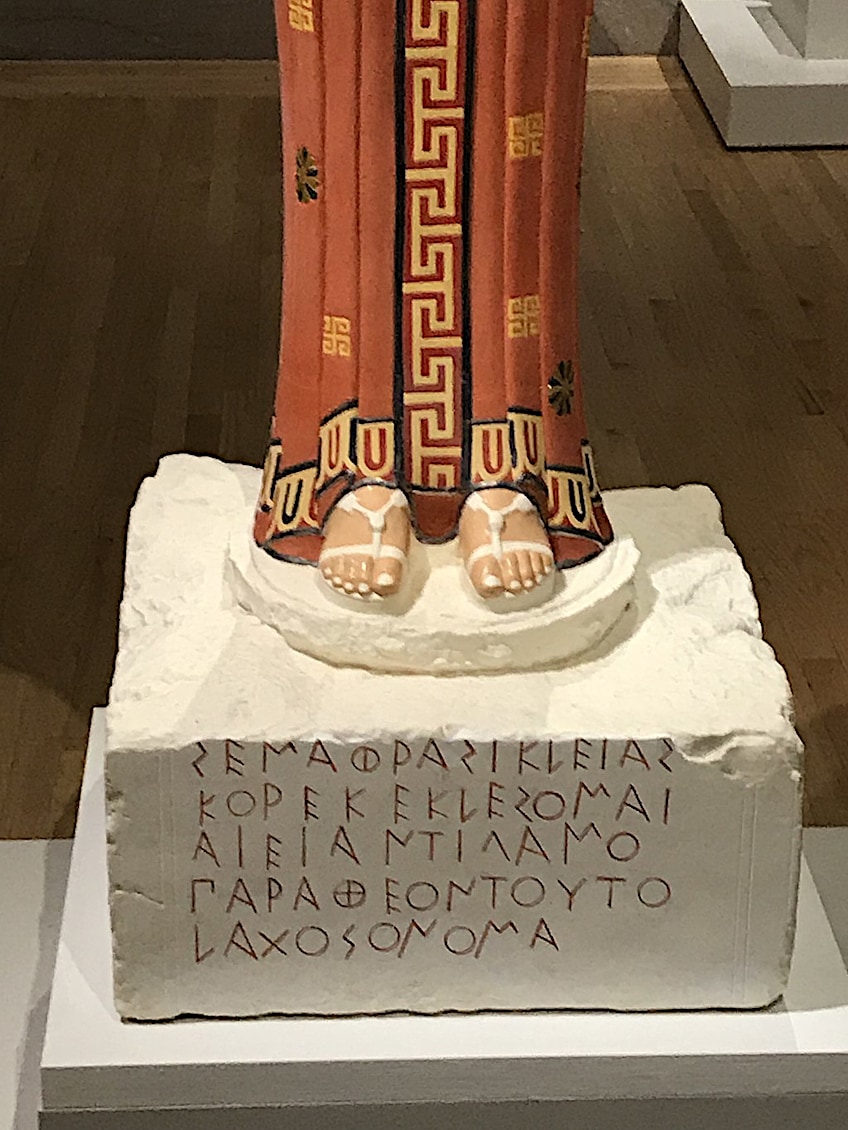

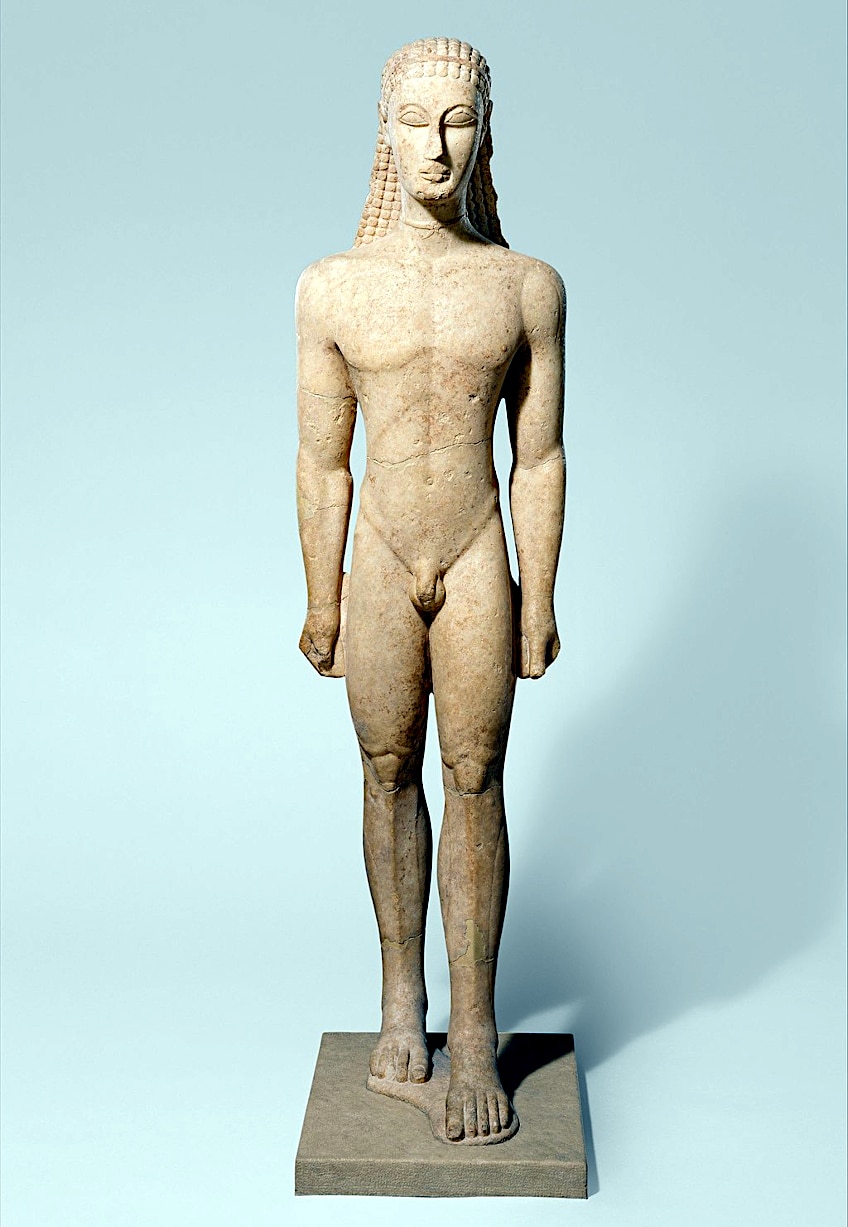

The male Kouros and the female kore were the most popular styles of freestanding, large-scale sculptures at this time. The kouros at the Metropolitan Museum is one of the oldest specimens of the kind, with Egyptian influence in both stance and dimensions. These enormous stone sculptures were erected beyond the city walls in temples and cemeteries as tributes to the gods or tomb markers. Athenian nobles regularly created costly burial monuments in the city and its surrounds, particularly for relatives who died when they were young.

Such memorials also took the shape of stelai, which were frequently adorned in relief. During the period, sanctuaries were a focal point of creative success and a key storehouse of works of art.

By the start of the sixth century B.C., the two primary orders of Greek architecture—the Doric order and the Ionic order were firmly established. All through the century, sanctuary architecture was perfected via a process of vigorous experimentation, typically through building projects undertaken by kings like Polykrates of Samos and Peisistratos of Athens.

These structures were frequently adorned with stone or terracotta sculpted figures, paintings (now mainly destroyed), and intricate moldings. True narrative sequences in relief sculpture first developed in the late sixth century B.C., when painters grew more interested in depicting figures in motion, particularly the human form. Athens created the Panathenaic games in 566 B.C. Triumphant athlete statues were placed in Greek sanctuaries as dedications, and trophy amphorae were adorned with the occasion in which the Olympian had triumphed.

During the sixth century B.C., innovation and invention took numerous forms.

Thales of Miletos, the oldest recorded Greek scientist, documented natural cycles and accurately guessed a solar eclipse and the solstices. Pythagoras of Samos was a powerful and forward-thinking mathematician who is best known for the theorem in geometry that bears his name. Solon, a lawgiver, and poet from Athens initiated revolutionary changes and produced a written system of rules.

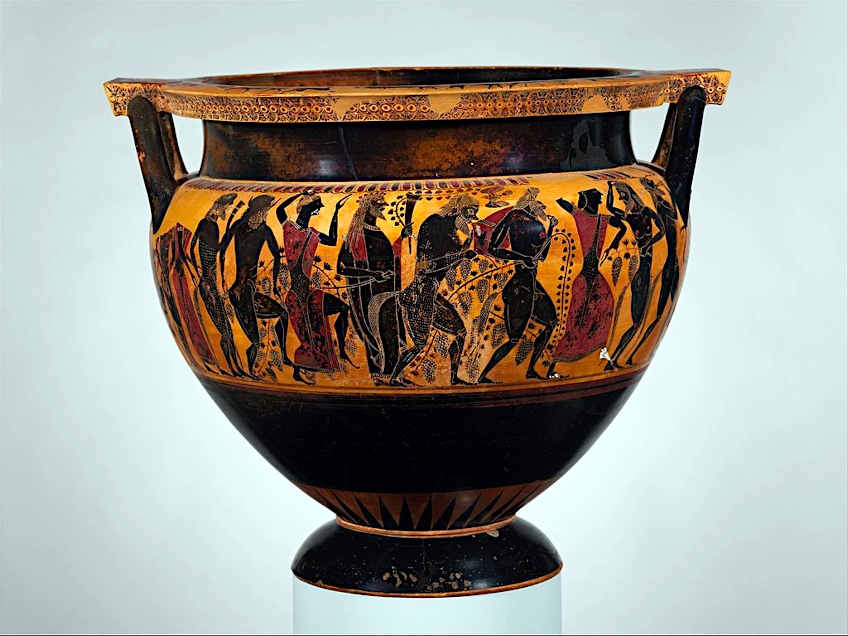

Meanwhile, potters at Athens acquired Corinthian methods, and by 550 B.C., Athenian—also known as “Attic” for the territory around Athens—black-figure pottery monopolized the Mediterranean export sector. Vases from Athens from the second half of the sixth century B.C. have a richness of artwork depicting burial ceremonies, daily life, symposia, sports, combat, religion, and folklore, among other things.

Sophilos, Kleitias, Nearchos, Exekias, Lydos, and the Amasis Painter were among the great artists of Attic black-figure vases who dabbled with a range of approaches to overcome the constraints of black-figure painting’s concentration on silhouette and etched detail.

The subsequent creation of the red-figure method, which allowed for more sketching options and finally supplanted the black figure, is traditionally dated to around 530 B.C. and credited to the potter Andokides’ studio.

Highlights of Art During the Archaic Period in Greece

- Festivals and games brought the diverse and varied Greek civilizations together, and they were subjected to art from other parts of the empire.

- The “Archaic Smile” appeared frequently in sculptures and sculpted figures and was intended to give the item a sense of life and well-being.

- Sculptors began to be more concerned with the size and realistic anatomy of the human form.

- With an emphasis on harmony, architects sought to improve the balance and proportion of their structures.

- The Orientalizing Style, the first departure from the geometric style of the past, was influenced by Eastern influences. This cultural adoption was not confined to the arts but also included myth, theology, and the written word.

- A left foot forward or incredibly detailed, helmet-like hair can also be used to identify archaic statuary.

- While we think of Grecian buildings and sculptures as being ordinary in their present white marble condition, these statues and temples were vibrantly colored in their day. Metal jewelry was also used to embellish several sculptures.

Archaic Greek Pottery and Archaic Sculpture

The archaic period is marked by a trend toward figurative and realistic approaches in the visual arts. It was during this time that monumental sculpture was brought to Greece, and Greek pottery styles saw significant transformations, from the late geometric period’s repetitive patterns to the earliest red-figure vases.

But what are the two major types of art of the Archaic period? Both ancient Greek sculpture and ancient Greek pottery had notable Orientalizing influences in the early archaic era.

Archaic Greek Sculpture

Greek sculpture consisted mostly of modest bronze pieces, notably of horses, at the start of the archaic era. Bronze human statues were also made, and both horses and humans can be seen in holy sanctuaries. Horse miniatures were increasingly less prevalent towards the end of the seventh century, eventually vanishing “nearly totally” by 700 BC.

Greek sculpture exhibited a considerable Eastern influence in the seventh century, with mythological animals such as griffins and sirens becoming increasingly prominent. Greek sculpture began to explicitly portray gods around the seventh century BC, a tradition that had previously been abandoned following the end of the Mycenaean period.

The archaic period in Greece saw the beginning of life-size human sculpture in hard stone. The dimensions of the New York Kouros closely adhere to Egyptian regulations governing the ratio of human forms, which was influenced in part by ancient Egyptian stone sculpture.

These sculptures are primarily known in Greece as church dedications and tomb markers, but the same methods might have been employed to create cult representations as well. The kore and kouros, near life-size frontal sculptures of a young woman or man, established in the Cyclades about the middle of the seventh century BC, are the most well-known kinds of archaic sculpture. The Dedication of Nikandre, which was offered to Artemis at her sanctuary on Delos around 650 BC, was probably the first kore made, and kouroi followed soon after.

Both people and divinities were represented by kouroi and korai. Some kouroi, such as the Naxians’ Colossus from circa 600 BC, are said to depict Apollo, while the Phrasikleia Kore was intended to resemble a young woman whose grave it was initially supposed to identify. Attic kouroi grew more realistic and naturalistic during the sixth century. This pattern, nevertheless, does not present elsewhere in Greece.

The genre began to fade in popularity in the late sixth century as the aristocrats who commissioned kouroi lost power, and by 480, kouroi were no longer being produced.

Archaic Greek Pottery

Archaic Greek pottery accounts for a significant percentage of the archeological record of ancient Greece, and as there is so much of it, it has had a proportionally large influence on our understanding of Greek civilization. The shards of ancient Greek vases that were abandoned or buried in the first millennium BC are still the best resource for learning the Greeks’ traditional way of life and worldview.

Several Greek pots were made domestically for everyday and culinary use, while superior pottery from Attica was purchased by other Mediterranean civilizations, especially the Etruscans of Italy.

There were various regional variants, most notably the ancient Greek ceramic styles from South Italy. At these places, many types and shapes of ancient Greek vases were used. Some were used as burial markers, some as tomb presents, and others, like later terracotta figurines, appear to have been viewed partially as objets d’art. Some were exceedingly beautiful Greek vases intended for aristocratic consumption and house ornament as much as storage or other functions, such as the krater, which was typically used to dilute wine.

The introduction of vase painting resulted in an increase in decoration in Greek ceramic art. Geometry-based artwork in Greek vase patterns developed in Greece at the same time as the Orientalizing period in the late Dark Ages and early Archaic period. Initially, black-figure ancient Greek pottery patterns were produced in Archaic and Classical Greece, but other variations, such as red-figure vessels and the white ground method, developed. West Slope Ware was representative of the latter Hellenistic era, which saw the extinction of vase painting.

The renaissance of enthusiasm in Greek art started quite some time following the restoration of classical studies during the Renaissance, and it was reinvigorated in the 1630s by intellectuals in Rome surrounding Nicolas Poussin.

Even though little collections of vases recovered from ancient cemeteries in Italy in the 15th and 16th centuries were established, they were classified as Etruscan. Although Lorenzo de Medici likely acquired numerous Attic vases directly from Greece, the connection between them and those unearthed in central Italy was recognized much later.

The majority of the early study on Greek boats was done in the form of producing books of the images they showed; however, neither D’Hancarville’s nor Tischbein’s folios document the forms or attempt to identify a date, rendering them untrustworthy as archaeological records. Throughout the 19th century, genuine academic research activities made steady progress.

The names we assign to Greek vase designs are largely dependent on tradition rather than historical accuracy; some are labeled with their original titles, while others are the result of early archaeologists’ futile attempts to link the physical item with a recognized term from Greek literature.

To better understand the relationship between form and function, archaic Greek pottery is divided into four key categories, each of which is shown below with examples of popular types: storage jars, mixing vessels, and Greek vessels for oils and fragrances.

Aside from their utilitarian applications, certain vase types were associated with rituals, while others were connected with sports and the arena. Although not all of their uses are known, researchers make reasonable guesses as to what role a component would have served where there is uncertainty.

Some, for example, are purely ceremonial. Some of the containers were designed to be used as grave markers. Males were distinguished by craters, while females were distinguished by amphorae. This allowed them to survive, and it is for this reason that certain funeral processions will be held.

The oil used as burial presents was discovered in white ground lekythoi that appeared to be prepared particularly for that purpose. There has been a global market for archaic Greek pottery since the 8th century BC, which Corinth and Athens controlled until the end of the 4th century BC. The extent of this trade may be determined by plotting the position maps of these vessels outside of Greece, albeit this does not account for gifts or immigration.

The discovery of Panathenaic in Etruscan burials could only be explained by the presence of a second-hand market. South Italian items began to dominate the Western Mediterranean export market as Athens’ political power waned over the Hellenistic period.

That wraps up today’s look at the art of the Archaic period in Greece. The two most prominent art forms of Archaic period art were Archaic sculpture and pottery. Sculpture and adorned pottery flourished throughout the Archaic period in Greece, notably vases in red and black styles. Near Eastern and Egyptian influences had a significant role in the transition from geometric standards to a more realistic style that contained animals, legendary beings, and botanical features.

Take a look at our Archaic period webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Archaic Greek Art?

The Greek Archaic period lasted from roughly 800 BC through the second Persian colonization of Greece in 480 BC, following the Greek Dark Ages and being succeeded by the Classical era. During the Archaic period in Greece, Greeks settled throughout the Mediterranean and Black Seas, as far east as Trapezus and west as Marseille, and by the end of the era, they were part of a Mediterranean commerce network. The Greek archaic era began with a significant increase in population and drastic transformations that rendered the Greek world unrecognizable by the end of the eighth century. During the archaic period, Greek administration, economics, foreign relations, warfare, and Archaic Greek art all evolved.

Exactly What Are the Two Major Types of Art of the Archaic Period?

In the visual arts, the archaic period is distinguished by a movement toward figurative and realistic methods. During this period, monumental sculpture was introduced to Greece, and Greek pottery styles evolved significantly, from the late geometric period’s repetitive patterns to the earliest red-figure vases. But what are the Archaic period’s two primary styles of art? In the early archaic era, both ancient Greek sculpture and ancient Greek pottery exhibited notable Orientalizing influences.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Archaic Greek Art – An Overview of the Greek Archaic Period.” Art in Context. May 6, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/archaic-greek-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 6 May). Archaic Greek Art – An Overview of the Greek Archaic Period. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/archaic-greek-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Archaic Greek Art – An Overview of the Greek Archaic Period.” Art in Context, May 6, 2022. https://artincontext.org/archaic-greek-art/.

Hi my name is Jason Eric Schumann and I was walking down an alley in Council Bluffs Iowa and I came across this sculpting I think you might be interested .I think it’s mid 7th century bc .