Caspar David Friedrich – An In-Depth Look at This Romanticism Artist

Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings boldly presented the observer with the sublime in order to convey a sensation of the limitless. Caspar David Friedrich’s artworks imbued the usually minor genre of landscape painting with profound theological and spiritual meaning. He used sunlit vistas and foggy plains to portray the divine’s magnificent force, feeling that the glory of the natural environment could only mirror the splendor of God.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Biography

Friedrich’s somber landscapes, which frequently immersed the spectator in the wilds of nature, elicited an emotional response from the observer instead of a more literal relationship with the environment. This combination of spiritual importance and artwork helped him become a great success. While conservative critics questioned Friedrich’s metaphorical and theological landscapes, the artist contended that his works never merely copied a picture, but rather gave a chance to reflect on God’s role in the universe.

Friedrich pushed the observer to embrace the immense force of nature as a testimony of a divine presence by using spectacular perspectives and foggy, untamed landscapes that overshadowed any individuals. Friedrich rejected the decorative conventions of landscape painting in favor of Romanticism’s concept of the sublime.

The artist expressed the immense force and permanence of the natural environment through his careful portrayals of mist, fog, gloom, and light; the observer is physically aware of his frailty and pointlessness.

| Nationality | German |

| Date of Birth | 5 September 1774 |

| Date of Death | 7 May 1840 |

| Place of Birth | Greifswald, Swedish Pomerania |

Childhood and Education

Caspar David Friedrich grew up in a conservative Lutheran household. He was subjected to grief at a young age, having suffered the loss of his mother to childhood ailments when he was only seven years of age, as well as the death of his two sisters. The death of Johann, his brother, who perished while attempting to save the then 13-year-old artist after he slipped through the ice, was arguably the most devastating loss.

Friedrich, who had been tutored, began taking painting classes from Johann Gottfried Quistorp in 1790.

His initial love for painting was supported, and he enlisted at the Copenhagen Academy when he was 20 years of age. He gained a lifetime passion for the environment and scenery while exploring the works of the master artists. Furthermore, he immersed himself in mystical and spiritual poetry, which influenced his subsequent work and laid the groundwork for his role as a pioneer of German Romanticism.

Early Career

In 1798, the painter completed his education and relocated to Dresden, where his works were well received. Friedrich championed Romantic principles, such as the spiritual capacity of art and the manifestation of religious impulses via the force of nature, from his early works.

The artist claims that “The ultimate purpose of man is not humanity, but the infinite, the boundless. Art is limitless, but all artists’ understanding and abilities are finite.”

The environment became Friedrich’s major vehicle for conveying visual expressions of the sublime, as shown in Morning Mist in the Mountains (1808). During the Napoleonic Empire, Friedrich’s commitment to the environment was also political, as he painted particularly German landscapes with a sense of confidence and authority that stretched virtually beyond earthly limits.

Many of his peers regarded Friedrich’s artworks through the prism of political autonomy and cultural heritage until Napoleon’s collapse in 1815, believing they carried the prospect of future freedom from foreign dominion.

Mature Period

Friedrich’s 1816 nomination to the Dresden Academy brought in a constant income, and he quickly gained fame as one of the founders of the Renaissance in Germany. This enabled his marriage to Caroline Bommer in 1818, at the age of 44. Despite his image as a loner who once declared, “in order not to detest people, I must eschew their company,” the union had an instant influence on his work.

In several of his works, he started to represent his wife, changing his well-established pattern of a lone person submerged in the countryside to sometimes include a couple.

Friedrich attracted the notice and favor of world leaders. When The Monk by the Sea (1810) was displayed at the Berlin Academy, he came into contact with Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig of Prussia, who then subsequently bought the two works. The royal family would continue backing Friedrich’s artworks until his political ideas led him to lose favor.

Tsar Nicholas I bought some of his pieces for his court; therefore, his artwork was widely accepted in Russia.

In 1830, Prince Alexander of Russia requested the painter to create a series of translucent drawings (since destroyed) that were to be displayed in a gloomy chamber lighted from behind and accompanied by music. Friedrich’s Romanticism inclinations discovered a kindred spirit in the well-known poet from Germany Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, whose works exemplify the movement’s literary development.

Nonetheless, Goethe’s systematic study with color theory reveals a more impartial and methodical attitude to the visual arts, which underpins their 1816 feud. Goethe recommended that Friedrich paint clouds to catalog their varied forms; Friedrich declined, believing that such studies would be incompatible with Romantic conceptions of nature’s holiness and would be purely a scientific endeavor.

Later Period

The murder of his colleague and fellow painter Gerhard von Kügelgen in 1820 triggered profound despair, and he resorted to lecturing for peace and comfort. During this decade, Friedrich’s profession faltered from a rising interest in Naturalism and Realism in German painting; his devotion to Romantic landscapes went out of favor.

As a result, he was refused the chair of landscape artwork at the Dresden Academy in 1824.

He became unwell shortly after and was not able to produce oils again until around 1826. By 1830, the increasingly lonely figure had become much more isolated from public life. He became increasingly depressed and distrustful of acquaintances and his wife, whom he mistakenly felt was cheating on him.

Some academics have characterized his last works as dismal thoughts on mortality and the passage of time since he chose to stay in the quiet of his studio and entertain only his closest family and friends. Nonetheless, his latter years were fruitful, with the development of significant pieces such as The Stages of Life (1835). Friedrich suffered a stroke on June 26, 1835, which left him largely immobile and confined his artistic productivity to sketches once more. He experienced a second stroke just before his death in May 1840, and he was reduced to destitution.

Legacy

Friedrich, a member of the second generation of German Romantics, went beyond the Nazarenes’ concepts of symbolism to develop a new, austere vernacular of recall rather than representation. His commitment to landscape painting as a substitute to conventional religious or historical painting inspired his peers to re-examine the genre.

This landscape format elevation would have domestic and international ramifications.

In the 19th century, many American painters studied in Dresden and learned from Friedrich’s approach. The Hudson River School painters, particularly, produced awe-inspiring vistas filled with political and spiritual importance. Friedrich’s intriguing use of symbolism to infer deeper connotations was also a major model for 19th-century Symbolists and 20th-century Surrealists, who praised his production of poetic sentiments.

Furthermore, his simplicity and large color fields laid the groundwork for Color Field Painting and Abstract Expressionism. This was verified in a 1961 essay by Robert Rosenblum, who clearly linked Friedrich’s The Monk by the Sea (1810) to the then-developing Color Field Painting style in the United States. In Germany, Friedrich was seen as the archetypal battling and triumphant creative energy, and Nietzsche is supposed to have had him in thought as the archetype human that imbued his philosophical notions of a vibrant, productive existence.

More notoriously, Hitler utilized the artist’s works to demonstrate German supremacy over other races. In recent years, the restoration of Friedrich’s artwork from Nazi propagandists’ abuse has impacted new generations of modern German painters, including Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer.

He exemplifies a strong Germanic ancestry while also evoking gentle evocations of loss and absence, both of which are essential subjects in postwar European art.

Caspar David Friedrich’s Paintings

Friedrich’s modest color palette and attention to light frequently produced an overpowering sensation of nothingness, which influenced Modern Art. His paintings’ visual simplicity was so uncommon that his viewers were frequently perplexed; one group of art aficionados who visited his workshop allegedly saw a piece upside down on the easel, assuming the clouds were ripples and the sea was the sky.

His use of muted color and the minimalism of his works that nonetheless conveyed significant thoughts would teach modernists.

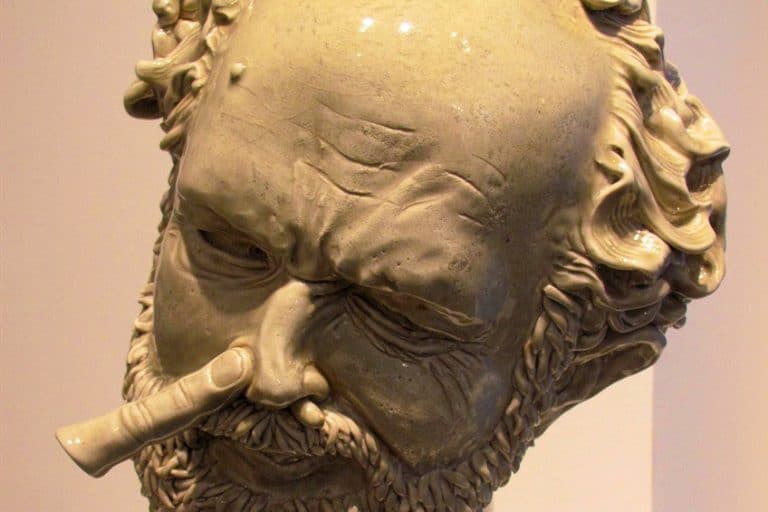

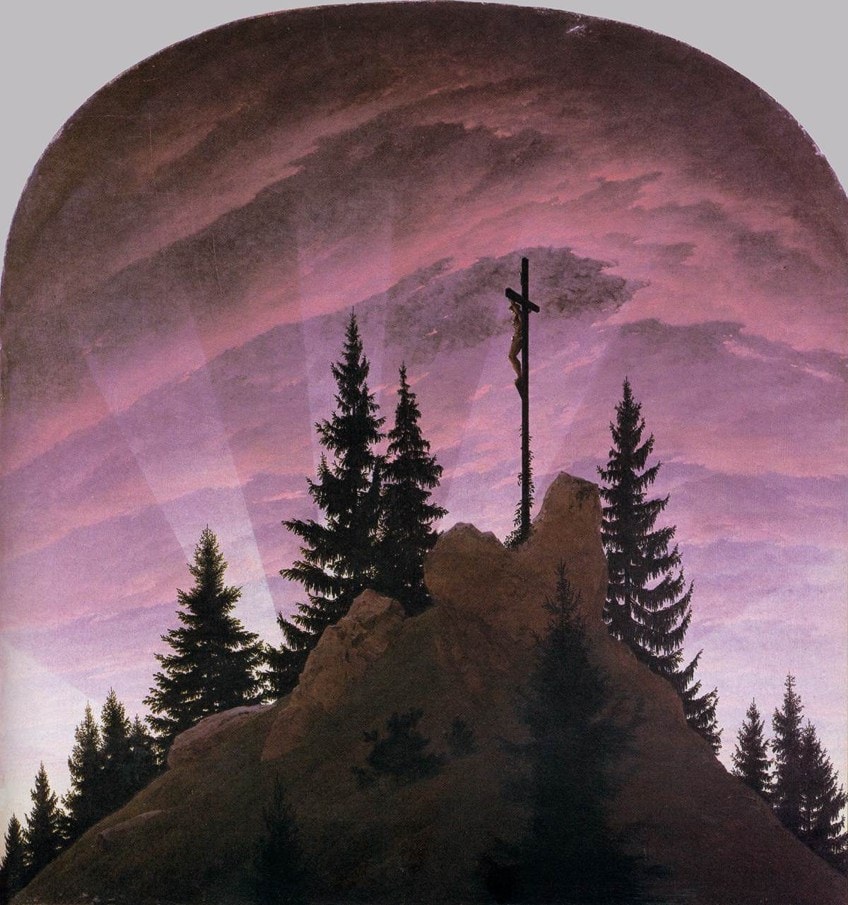

Cross in the Mountains (1808)

| Date Completed | 1808 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 115 cm x 110 cm |

| Current Location | Gemaldegalerie Neue Meister, Dresden |

Friedrich’s artwork depicts a pine-covered mountainside with a big cross on it. The cloudy sky is depicted in pink, red, and violet hues that transition from dark to bright from top to base of the canvas. Five light beams emerge from afar, an invisible horizon. The curved canvas is framed in an ornate frame created by the artist but constructed by his colleague Gottlieb Christian Kuhn.

The frame depicts a variety of Christian motifs, such as the heads of five infant angels, a star, grapevines, maize, and God’s eye. It is one of the earliest examples of Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings, and it includes many of the Romantic elements and issues he would explore throughout his oeuvre, most significantly the landscape’s crucial meaning.

Despite the presence of a crucifix on the altarpiece, the focus is on the spiritual element of creation. “High up on the peak sits the cross, encircled by fir trees, and evergreen ivy twines around the foot of the cross,” he said of the sculpture.

The sun is setting, and Christ on the cross glows in the red light. The cross is built on a boulder, as solid as our trust in Jesus Christ. Fir trees grow all around the cross, evergreen and eternal, like men’s trust in Him, the wounded Christ.”

This was a game-changing reinvention of the landscape painting style, elevating it to a new point of optimum relevance.

It expressed Friedrich’s idea that God’s majesty could be found most clearly in nature. While Friedrich was intensely religious, seeking to create a vision that would portray God’s might more clearly than words could, his method was very divisive. In 1808, when he opened his workshop to the public, letting people see this artwork, Wilhelm von Ramdohr contended that landscapes could not serve as an altarpiece. Friedrich and his allies openly defended the picture, and the ensuing dispute contributed to Friedrich’s renown.

Morning Mist in the Mountains (1808)

| Date Completed | 1808 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 71 cm x 104 cm |

| Current Location | Thuringer Landesmuseum Heidecksburg, Rudolstadt |

This simple picture of a mountain peak covered in a white mist of early morning fog, accompanied by barely perceptible pine trees and rocky outcroppings, expresses Friedrich’s Romantic landscape concepts. The grandeur and usage of light in this majestic, faraway vision of massive nature suggested a link to a higher power. A sliver of light shines through a gap in the clouds, as though lighting the mountain top with heavenly light.

The representation of mist was a crucial metaphor for the artist in achieving this religious message. As he put it, “When a landscape is shrouded in fog, it seems grander and more magnificent, heightening the intensity of the mind and eliciting anticipation, much like a veiled lady. The eye and fancy are more drawn to the misty distance than to what lies close and far ahead of us.”

He sought to immerse the observer in the perception of the natural domain by placing us in front of this wide expanse with no feeling of the foreground; a spectacular field that he believed most nearly portrayed the majesty and might of God.

The Monk by the Sea (1808-1810)

| Date Completed | 1808-1810 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 110 cm x 171 cm |

| Current Location | Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin |

This painting, perhaps one of Friedrich’s most significant and well-known works, catapulted the painter to international recognition when it was displayed at a Berlin art exhibition in 1810. The upper three-quarters of the painting, which displays a blue-gray sky and green water, dominate a wide, barren countryside. The forefront is an uneven area of beige soil with a guy standing just left of center. Despite having his back to the observer, he may be identified by the long, black robe of a monk. The canvas is packed with broad swathes of color, accented by little brushstrokes of white to represent wave crests and birds in the sky.

It is a masterwork of simplicity and graphic restraint that evokes a sense of awe, amazement, and humility.

The strong reaction to this painting assisted Friedrich’s admittance as a fellow of the Berlin Academy, as well as the approval of Prince Friedrich Wilhelm Ludwig of Prussia, who purchased the piece for the royal collection; a significant distinction. Aside from the awards, this piece exemplifies Friedrich’s experimental attitude. Any traditional method of landscape painting is no longer in use. The compositional structure seems uneven and lacks a viewpoint focal point at first inspection.

Rather than depicting a scenario, Friedrich has provided a chance for the audience to feel a spectrum of emotions that the artist has simply indicated. If he had added additional details, the spectator would have been tempted to build a narrative or plot, but with this basic minimum, we are simply left with sensory information.

This new method of constructing landscapes promoted the concept that the observer should examine the majesty of the natural environment and interpret spiritual expressions into it. Profound meaning in a minimalist, non-narrative manner would be crucial to modernist abstraction. This picture, particularly, has been related to Mark Rothko’s post-World War II Color Fieldworks, which were likewise meant to develop a spiritual encounter for the observer.

While Friedrich frequently painted landscapes absent of any human presence, this work demonstrates his second technique to imbuing the environment with greater importance and relationship with the audience: the employment of a stand-in.

One of the fundamental ways German Romanticism differs from French and British Romanticism is the single figure oriented towards and in connection with the landscape. Although Romanticism was concerned with the relationship between humanity and nature throughout the world, British painters emphasized more sentimental or bucolic landscapes, while French artists frequently implied man’s inclination to control nature; the German method portrays humanity’s endeavor to comprehend nature and, by implication, the divine.

This tendency for an emotional link between the spectator and the picture supplanted more technical or illustrative techniques, as shown by Friedrich’s melancholy landscapes, which frequently plunged the observer into nature’s wilds.

The Abbey in the Oak Wood (1809-1810)

| Date Completed | 1809-1810 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 110 cm x 171 cm |

| Current Location | Nationalgalerie, Staatliche Museen Zu Berlin |

This picture represents the decaying remnants of a Gothic monastery situated amongst a landscape of barren leafless trees. It is a study in subtle hues, portrayed in delicate shades of yellows, browns, and white. Cross marks and gravestone outlines are dispersed around the surviving wall of the abbey entryway with its tall narrow window. The meager form of a few monks may be seen preparing to pass via what is left of the church’s door, possibly on their way to grieve those who had passed.

In his works, Friedrich frequently featured vestiges of Gothic architecture, such as the abbey ruins. This expresses a sense of patriotic pride in the memorials of the German Gothic past, which were especially important under the Napoleonic rule.

The Gothic was also a time when spiritual importance was embedded in a wide spectrum of artistic expression. German Expressionists in the twentieth century would likewise turn back to the Gothic as a symbol of identity and religious power.

This picture also demonstrates Friedrich’s superb use of negative space and emptiness to convey a feeling of grief and longing.

The representation of rubble and barren trees implies death and desolation, which is heightened by the dreary, subdued color palette and inconsistent compositional balance. The bulk of the painting, like his The Monk by the Sea, portrays simply empty sky. The message, however, is not pessimistic: soft light implies the sun shining through the clouds, and the oak trees are bare but not dead. Regeneration and resurrection are promised.

Wanderer above a Sea of Fog (c. 1818)

| Date Completed | c. 1818 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 110 cm x 171 cm |

| Current Location | Kunsthalle Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany |

This picture portrays a lone man, dressed properly and clutching a walking cane, poised on a rocky protrusion and gazing out across an unfriendly horizon. He stands completely motionless, just his hair tousled by an invisible breeze, against a churning field at his feet. A sky loaded with white fluffy clouds and the shape of mountaintops just discernible through the mist can be seen in the distance. The profundity of nature is displayed not in a quiet, tranquil perspective, but in the sheer might of what natural powers may do when the man examines the grandeur before him.

Friedrich is recognized for making political messages in his paintings, which were frequently veiled in subtle ways.

The figure’s attire was donned by academics and many others during the Wars of Liberation in Germany; by the time this picture was completed, the garment had been banned by Germany’s new governing party. By painting the person in this clothing on purpose, he made a visible – if muted – statement against the current regime. However, the political significance of this piece did not end there; his work (particularly this picture) was embraced and exploited by the Nazi dictatorship as emblems of passionate German nationalism.

Friedrich’s paintings were easily reworked to match changing political goals since he substituted a more literal portrayal with only suggestive meaning.

On the Sailing Boat (c. 1819)

| Date Completed | c. 1819 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 71 cm x 56 cm |

| Current Location | Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia |

This piece depicts the bow of a ship sailing towards the horizon. A gentleman in a blue coat and headgear and a woman in a long dress with a white lace collar hold hands as they look ahead. The right side of the canvas is taken up by a close-up of the sail and the boat’s mast. The spectator may see the faint shape of buildings silhouetted in mist in the distance. The canvas’s biggest width is taken up by a gleaming golden sky.

This piece, a deviation from his regular landscape formula, makes a link between the painting’s spectator and the location through its implicit story and more conventional use of symbolism.

We are passengers on the ship, watching the brave pair on their adventure. This picture, completed one year after Friedrich’s wedding to Caroline Bommer, demonstrates his shift from lone individuals to the occasional representation of a duo. These feminine figures were frequently modeled on his wife’s image; the pair featured in this picture is thought to be portraits of the painter and his wife.

Their linked hands represent their new, joyous union, and their presence aboard a moving ship represented a new life they are starting.

Recommended Reading

We hope that you have had fun learning about Caspar David Friedrich’s biography and artwork. Perhaps you would be interested to learn more about Friedrich’s artwork and life. Therefore, we have created a list of suitable reading material just in case you would like to do so.

Caspar David Friedrich (2006) by Werner Hofmann

Werner Hofmann brilliantly illustrates Caspar David Friedrich’s exceptional ability to faithfully portray the natural environment while integrating it with spiritual and theological meaning. Caught between the close and the far, the limited and the infinite, his images find a place in which to reflect on nature and the holy. Hofmann investigates contemporary assessments and influences on Friedrich’s artwork while carefully situating the artist in a larger perspective.

Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings openly conveyed the sublime to the viewer in order to create a sense of limitlessness. Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings instilled tremendous religious and spiritual depth into the typically small field of landscape painting. He employed bright vistas and misty plains to depict the divine’s great energy, believing that the majesty of nature could only reflect God’s brilliance.

- A vivid demonstration of Caspar David Friedrich's amazing abilities

- Examines contemporary judgments of and influences on Friedrich

- Includes 193 beautiful illustrations, 150 of which are in color

Caspar David Friedrich (2017) by Johannes Grave

This gorgeously illustrated collection on the contentious 19th-century Romantic artist, now published in a new format, answers his modern detractors while enhancing our admiration for his exceptional creativity. “A picture must stand as a painting, fashioned by human hand,” Caspar David Friedrich stated, “rather than strive to masquerade itself as Nature.” Friedrich, one of the most prominent painters of his period, conjured landscapes of immense beauty and devotion within the limitations of his studios.

- Illustrated volume on the controversial 19th-century Romantic artist

- Addresses his critics while deepening our appreciation for his genius

- Highly readable, insightful, and copiously illustrated

And with that, we conclude our article on the artist Caspar David Friedrich. What we have discovered is that Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings openly conveyed the sublime to the viewer in order to create a sense of limitlessness. We have also learned that Caspar David Friedrich’s paintings instilled tremendous religious and spiritual depth into the typically small field of landscape painting. He employed bright vistas and misty plains to depict the divine’s great energy, believing that the majesty of nature could only reflect God’s brilliance.

Take a look at our Caspar David Friedrich paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Caspar David Friedrich Known For?

Friedrich’s dismal landscapes, which frequently submerged the observer in nature’s wilds, prompted an emotional reaction from the observer rather than a more literal interaction with the environment. This blend of spiritual significance and artwork aided him in becoming a huge success. While conservative detractors questioned Friedrich’s symbolic and spiritual landscapes, the artist insisted that his works never simply replicated an image, but rather provided an opportunity to consider God’s role in the cosmos.

What Defined Friedrich’s Artwork?

By employing stunning views and hazy, untamed landscapes that dwarfed any persons, Friedrich challenged the observer to accept the great force of nature as a testimonial of a heavenly presence. Friedrich abandoned landscape painting’s ornamental norms in favor of Romanticism’s idea of the sublime. Through his precise depictions of mist, fog, darkness, and light, the artist emphasized the overwhelming force and permanence of the natural world; the spectator is physically aware of his weakness and pointlessness.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Caspar David Friedrich – An In-Depth Look at This Romanticism Artist.” Art in Context. February 28, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/caspar-david-friedrich/

Meyer, I. (2022, 28 February). Caspar David Friedrich – An In-Depth Look at This Romanticism Artist. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/caspar-david-friedrich/

Meyer, Isabella. “Caspar David Friedrich – An In-Depth Look at This Romanticism Artist.” Art in Context, February 28, 2022. https://artincontext.org/caspar-david-friedrich/.