What Is Video Art? – Discover the New Age of Visual Art

What is video art, and what are video artists? Video recordings, films, and video projections are used as expressive or creative mediums in video art. While the history of video art only goes back a few decades, it has proven to be a very popular medium. Below, we will take a deeper look into the definition of video art, and explore the most significant video art examples.

What Is Video Art?

After its inception in the early 1960s, video emerged as a thrillingly immediate medium for video artists. The pricey technology, which had previously only been attainable in the corporate broadcasting sector, encountered a breakthrough when Sony developed affordable consumer-level equipment that gave everyday individuals the opportunity to explore new possibilities in documenting life around them. Understandably, this piqued the curiosity of more experimental artists of the period, particularly those participating in related movements such as Performance art, Conceptual art, and experimental film.

It provided an inexpensive way of recording and depiction through a dynamic new channel, upending an art world where genres like photography, painting, and sculpture had long been considered the standard. This increased the opportunity for unique creative voices and pushed artists to reach new heights in their professions. It has also produced a number of artists who would not have entered the fine art profession if they had been constrained by the limitations inherent in traditional art mediums. Over the last 50 years, video has become increasingly accessible to the general public, resulting in the continuous evolution of its application; we live in a time where even your average smartphone can produce high-quality artwork through the use of an ever-expanding array of digital apps.

The History of Video Art

We now see video art as a legitimate form of artistic expression with a distinct set of rules and history. It is regarded as a genre as opposed to a movement in the classic sense, and should not be conflated with experimental or theatrical filmmaking. While the mediums appear to be interchangeable at times, their varied origins enable art historians to regard them as being distinct from one another. Because video is such a popular medium, several art schools now offer it as a specialist art major.

Even though artists have been creating moving pictures in some form since the early 20th century, the first pieces that are more widely referred to as “video art” first appeared in the 1960s.

The Father of Video Art

Nam June Paik, the Korean-American Fluxus artist, popularized video as a viable creative medium in 1965 when he declared that his video of the Pope’s visit to New York was an important piece of art. When Nam June Paik happened to see the pope while sitting in traffic, he captured it on his Portapak and subsequently presented the barely edited and grainy result at the Cafe A Go Go in Greenwich Village. Some art historians, though, have dismissed Paik’s assertion that he employed the Portapak, claiming that Sony did not actually release that model until 1968. What is undeniable is that this video, along with the artist’s Fluxus exhibition at Galerie Parnass in Paris in 1963, where he displayed his first revised television sculptures, were among the first pieces of art created using the newly emerging video medium.

After his landmark 1965 presentation, Paik composed a brief manifesto urging activists and artists to make use of video as a tool for empowerment to rebel against the status quo, particularly what he called “one-way” broadcast television companies. This was the start of a long career-long quest for a utopian vision that Paik would pursue. He also stated that “like collage supplanted paint with oil, the cathode ray tube would one day replace the canvas”. He later pioneered the use of video installation, broadcast, artist screenings, and live events, all of which are still used by artists today.

The Spread of Video Art

Many of the prominent figures in video art began to create their most noteworthy works in the 1970s. Many of these early practitioners, like Paik, were keen to learn more about the medium’s ephemeral and fleeting features. It was employed to advance the conceptual objectives of American artists such as Joan Jonas, John Baldessari, and Bruce Nauman.

In the United Kingdom, David Hall fought hard for video art to be recognized as a true artistic form, writing extensively on it as a medium while also creating significant pieces of his own. In the 1970s, there was also a passion for employing video as a tool for activism.

It served as a means of documentation, which some activists saw as a chance to prove the wrongdoings they were trying to correct; and it also provided a strong, evident presentation of their message. Videofreex’s Davidson’s Jail Tape (1971) was a powerful representation of this. A member of Videofreex captured seldom-seen raw footage of his trip on the bus to jail, his detention in the cell, and a close-up look at the detainees after their arrest at the 1971 May Day celebrations in Washington, D.C.

The Role of Technology in Art

Video artists’ work was impacted when new and developed technologies including special effects, color television, consumer electronics, thermal imaging, security cameras, and video projection were introduced. The toolbox accessible to artists in the 1980s was exponentially greater than in the previous decade, allowing them to create exceptional video artworks.

Laurie Anderson used voice distortion regularly, most notably when she developed a digitally altered version of her voice called The Clone. Bill Viola rose to prominence for his use of super slow motion. Gary Hill would proceed to conduct extensive research into electronic language and sound, developing his own electronic linguistics. Furthermore, several of the most notable experimental filmmakers were interested in video and eventually created highly acclaimed video art practices that coexisted with and inspired their cinema-based work.

Later Developments

Nam June Paik’s early predictions of video art’s power have come true, at least in part. While the medium of video art has not yet completely supplanted more traditional forms in the modern art world, it has grown into a vast sector that clearly complements them. Modern video art practices continue to evolve in terms of both content and form, enabling video artists to explore new ideas and technology. For instance, the rise of high-definition digital video over the previous decade has made it possible for artists to create work with greater clarity. This technology is now widely available through a plethora of user-friendly and DIY software programs that are easily adaptable across tablets, PCs, cameras, cellphones, and the Internet.

This has expanded the context for how and where art may be displayed. Modern-day video artists draw inspiration from earlier video art pioneers while also bringing a deeper understanding of the ever-changing technology to the table.

Certain instances are more true to the video’s origins, such as the highly atmospheric and large projections of Phillippe Parreno, the French artist, or the increasingly architecturally-scaled and elaborate video installations of Pipilotti Rist from Switzerland, both of whom use special effects and cutting-edge projectors to push the medium in increasingly visually arresting and complex directions. The Clock (2010) by Christian Marclay, which lasted for 24 hours and contained a mash-up of pictures of clocks from legendary movie moments, hints at Warhol’s adoration of real-time footage with sprinkles of the video collagist.

In addition, Andrew Thomas Huang received international prominence in 2007 with Doll Face, which was a critique of the effect of television on our self-image. Ryan Trecartin is well-known for providing a homosexual male perspective to video art by inserting often garishly displayed stereotypes into otherwise mundane photos and video footage. With cutting-edge video works, certain video artists convey indications of the post-millennial era. Cory Arcangel’s most renowned work, Super Mario Clouds (2002), included pixelated graphics of the well-known video game drifting through blue sky on a website that can still be viewed on the online video site, YouTube. Although the piece was first launched in a gallery on numerous screens of varying heights and widths to give a completely immersive experience, the internet film is now all that exists. Hannah Black, a brilliant British artist, typically gets web material by putting in search phrases to uncover fragments that will eventually shape her themed collage videos.

The Styles and Concepts of Video Art

Video enabled artists from many groups to broaden their artistic arsenal and communicate their unique views in a previously unachievable quick manner. Because of the mobility and convenience of the use of video, practitioners were able to film their acts or performances in previously imagined ways. These artists all employed video to create extremely personal and direct artworks that would not have been achievable in any other medium available at the time.

Thus, technological advancement corresponded to a development in creative capability.

The Influence of Television

The increasing popularity of publicly-broadcast television had a profound effect on early video art practitioners. Artists like Martha Rosler and Wolf Vostell used parodies of advertisements and television shows to illustrate what they viewed as TV’s increasingly pernicious power. Several feminists of the time used videos to highlight societal sexism through popular culture. For example, Dara Birnbaum deconstructed iconic television shows with significant female characters, such as Wonder Woman, which she then collected into moving visual pictures that challenged objectification and stereotypes. Others, such as Brian Hoey, used live video feeds in their works to mirror audience imagery back at themselves, challenging spectators to consider their own passive role in television’s dominance over society.

Defying the Conventions of Film

Film had already been well established as an effective form of entertainment, an outlet for telling tales, and an all-encompassing popular choice in confronting the multiplicity of human experience while video art was still in its infancy. However, video artists were eager to grant themselves the freedom to disregard Hollywood standards, even the rules of narration, and started experimenting with presenting moving visuals and sounds on their own terms. This implied pieces that defied conventional concepts of story or character development, instead presenting images that expressed an artist’s mood, or message.

In some circumstances, video provided no explanation but rather lets the audience experience an emotion, ponder on a specific topic, or get a look inside the mind of the artist, as chaotic or quiet as it may be.

These works had a significant influence and contradicted everything that film was meant to represent. This defiance may be applied to nearly all video artists from the 1960s to the present – particularly, Andy Warhol eliminated cinema’s concept of presenting extended narratives in confined spaces. In Vertical Roll (1972) by Joan Jonas, we see the artist’s self-portrait gradually expanding through random pictures of her body interwoven with various objects and materials – a distinctively non-narrative collage, revolutionary in its non-linearity.

The Medium of Video

Video is a modified, warped, amplified, and altered electrical signal. An interest in video for these intrinsic properties was comparable to an abstract artist’s interest in brushes, oils, forms, and design for many video artists. Some artists created works that experimented with the medium itself, and as technology has advanced, so have the possibilities for employing video for its material characteristics. Peer Bode, a major figure in this area, has been executing this form of mechanical integration since the 1970s.

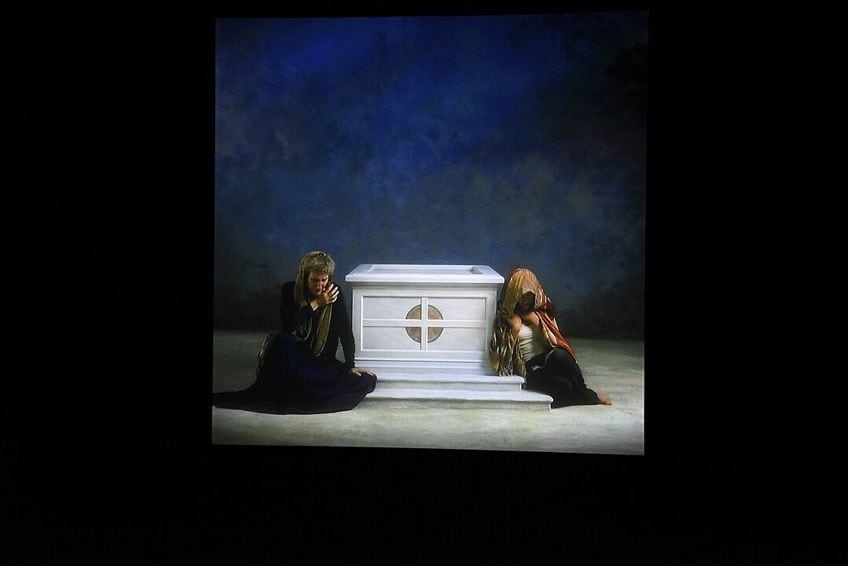

In his 1979 work Flute with Shift, we see a representation on screen of an individual playing the flute that varies in brightness in response to the regulated analog synthesizer parameters of the live flute sounds. Skip Sweeney was renowned for his installations that experimented with abstract image processing, video feedback, and synthesis. Bill Viola has always used video to generate multi-layered effects that aesthetically complement his explorations into humanity, spirituality, the body’s location in relation to the context of space, time, experience, and other inquiries into our existence.

Installation Art

Paik and Vostell’s early works, which included TVs as sculptural components, lay the groundwork for later “video installation” pieces. Contemporary video art displayed in a gallery space can be categorized as “single-channel”, (which implies the use of a single screen), or “installation” works, which are meant to be projected into a venue for exhibition, possibly with multiple images and including additional components such as sculpture or props. Pioneers of video installation as an art form include Bill Viola, Gary Hill, and Joan Jonas, who took full advantage of the architectural characteristics of a gallery’s space, fully immersing their work inside the space.

Again, the advancement of display technology has had a significant influence on the type of art created.

Video Art Examples

Some artists have utilized video art to challenge our perceptions of Hollywood cinema and attempt to dismantle them. These artists use the canvas appropriated from the cinema to dispel preconceptions of what is appropriate or enjoyable by eschewing the standard blueprints of routine narration, or by providing deeply private and taboo subjects as artworks, or by shaking up our thoughts about how a film should feel and look. Beyond its capacity for recording, video is a popular medium among artists who create pieces that resemble more conventional art forms such as sculpture, painting, collage, or abstraction.

This could manifest as a visual representation made of a sequence of hazy, spliced scenes. It could take the form of a performance video intended for contemplation on movement or spatial perception. It might be actual video equipment as well as its output as elements in a piece. Finally, it might be a work that would not be possible without the use of distortion or other types of audiovisual manipulation. Let us find out more about this medium by examining a few notable video art examples.

Sun In Your Head – Television Décollage (1963) by Wolf Vostell

| Artist | Wolf Vostell (1932 – 1998) |

| Date Created | 1963 |

| Medium | 16mm film transferred to video |

| Duration (minutes) | 7 |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Wolf Vostell, a German artist, distorted and toyed with numerous single frames obtained from television and film footage of the time for this video. The result is a flickering, fast-paced jumble of televisual pictures that range from flashing, abstract patterns to recognizable forms. The piece was displayed as part of Vostell’s ‘happening’ in Wuppertal, Germany in 1963. Due to the lack of video playback technology at the time, Vostell used a film camera to capture pictures from a television set, enabling him to edit the work and show it again on a projector.

This film served as one of the first to investigate the potential of television as an artistic outlet in its own right, with its highly experimental style and subversive form.

It makes use of his inventive application of the decollage method, which was coined by the Nouveau Realisme movement from France to refer to their shredding, erasing, and rewriting of old Parisian posters to produce new information. It was used by Vostell to describe the layering and re-mixing of sounds and images that he utilized to establish a new aesthetic language in his video art. Vostell is regarded as one of the most prominent early video artists, having pioneered the European components of the Happening and Fluxus movements. In 1958 he first used a television set as a piece of art and was the first artist to do so.

Sleep (1963) by Andy Warhol

| Artist | Andy Warhol (1928 – 1987) |

| Date Created | 1963 |

| Medium | Black and white film |

| Duration (minutes) | 320 |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

Andy Warhol filmed his lover and friend John Giorno sleeping for 320 minutes for this video artwork. Due to the piece’s length, only a few people have seen it from start to finish, yet it is regarded as one of the first and most significant examples of durational art. The movie explores issues of repetition, intimacy, and duration.

It is one of the first instances of what Warhol referred to as his “anti-films”, in which he employed extremely long, single takes to document his daily life and that of his companions.

Although it is considered a film as opposed to a video, the artist’s use of the camera, in which he simply turned it on and walked away, brings it closer to an artwork than a film because he is obviously intending to critique Hollywood’s storytelling conventions and its deliberate manipulation of real-time through editing. The filmmaker’s utilization of such epic duration has had a huge influence on many modern cinema and video artists active presently. In 2004, Sam Taylor-Wood’s 60-minute film of David Beckham sleeping closely echoed Warhol’s work.

Tv-Cello (1964) by Nam June Paik

| Artist | Nam June Paik (1932 – 2006) |

| Date Created | 1964 |

| Medium | Video tubes, tv chassis, electronics, and wiring |

| Duration (minutes) | 300 |

| Location | Walker Art Center, Minnesota, United States |

Nam June Paik was a pioneer in breaking down barriers between technology and art. TV Cello is an iconic example, designed specifically to be performed by Charlotte Moorman, the avant-garde cellist.

The installation included three television sets stacked on top of one other, each displaying a separate moving picture – a collaged video of other cellists, a clip of Moorman’s live performance, and a broadcast feed.

The entire artwork was also a fully functional cello, meant to be played with a bow to produce a succession of raw, electronic notes that resonated throughout the chamber. Paik was one of the first artists to legitimize video as an acceptable creative medium by exploiting the t.v.as an art object. He sought to call into question the television’s increasingly dominating position in molding public opinion by moving it out of its natural context and applying it in such subversive acts.

Art Make-up (1968) by Bruce Nauman

| Artist | Bruce Nauman (1941 – Present) |

| Date Created | 1968 |

| Medium | 16mm film |

| Duration (minutes) | 40 |

| Location | The Museum of Modern Art, New York City, United States |

This video comprises four films set in the artist’s studio in which he carefully and systematically applied various layers of color on his nude torso – white first, then green, pink, and ultimately black. The title alludes to the artist’s medium, the concept that he is “creating himself” for the observer, and questioning what an artist is made of. By exhibiting these four representations of himself, none of which can be claimed to be the real person, the artist was investigating the limits between masquerade, disguise, and reality.

Each ten-minute segment was initially meant to be shown on four independent displays on the walls of a single square room, with the artist never seen without a colored mask.

Nauman was among the first video artists to use the fixed-camera single-take approach shown in this video – an approach in which the scene is captured from a single point of view in one session. This gave the work an atmosphere of authenticity, and the absence of editing or varying shots allowed for a rejection of the standard cinematic paradigm, which was crucial to many of these video artists. These artists used the new medium to chronicle and develop ideas about live performance, influencing future generations of artists. The piece is an important representation of the artist’s use of his own body as an instrument for artistic investigation, in addition to his innovative use of video that pushes the potential of art creation to new limits.

That wraps up today’s look at the history of video art and important video artists. Not only did we explore how this medium rose to popularity, but we also looked at a few significant video art examples. Since its inception in the 1960s, video art has grown in accessibility as equipment and tools have become cheaper. This medium has allowed artists a means by which they can express themselves in ways that are not limited by the traditional forms of art. This has allowed novel forms of expression to arise in an otherwise rather stifling and formulaic medium that is usually used for the production of crowd-satisfying mainstream films.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Definition of Video Art?

Video art is a new sort of modern art and an outlet of expression that is widely seen in installations, as well as presented in a stand-alone format. Recent improvements in video and digital technology, allowing artists to edit and control film sequences, have helped open up a whole new avenue of creative potential and drew countless artists into the genre. It was pioneered by innovative artists such as Wolf Vostell, Andy Warhol, and Nam June Paik. Many of America’s top art schools now offer video art theory and practice as a Minor degree course.

What Are the Characteristics of Video Art?

Installation and single-channel are the two most common types of video art. An art video is displayed or exhibited as a single series of pictures in single-channel works. Installations are often composed of a setting made up of numerous independent pieces of video exhibited concurrently, or of videos combined with performance or assemblage art. Installation video is now the most popular type of video art, as it is part of the multi-media trend of mixing design, architecture, sculpture, electrical art, and digital art.

Duncan completed his diploma in Film and TV production at CityVarsity in 2018. After graduation, he continued to delve into the world of filmmaking and developed a strong interest in writing. Since completing his studies, he has worked as a freelance videographer, filming a diverse range of content including music videos, fashion shoots, short films, advertisements, and weddings. Along the way, he has received several awards from film festivals, both locally and internationally. Despite his success in filmmaking, Duncan still finds peace and clarity in writing articles during his breaks between filming projects.

Duncan has worked as a content writer and video editor for artincontext.org since 2020. He writes blog posts in the fields of photography and videography and edits videos for our Art in Context YouTube channel. He has extensive knowledge of videography and photography due to his videography/film studies and extensive experience cutting and editing videos, as well as his professional work as a filmmaker.

Learn more about Duncan van der Merwe and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Duncan, van der Merwe, “What Is Video Art? – Discover the New Age of Visual Art.” Art in Context. August 30, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/what-is-video-art/

van der Merwe, D. (2023, 30 August). What Is Video Art? – Discover the New Age of Visual Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/what-is-video-art/

van der Merwe, Duncan. “What Is Video Art? – Discover the New Age of Visual Art.” Art in Context, August 30, 2023. https://artincontext.org/what-is-video-art/.