Kandinsky Paintings – Exploring the Best Wassily Kandinsky Artworks

Wassily Kandinsky’s artworks are among the most influential of the abstract art genre. Kandinsky’s abstract art mirrored the belief that “things harmed images,” thus he experimented with shapes and colors to elicit mysticism and human feeling. Kandinsky’s paintings communicated their unique visual vocabulary that surpassed the material reality to depict the human condition. Wassily Kandinsky’s portraits and famous circle artworks have made him one of modern art’s most prominent characters.

Table of Contents

An Introduction to Wassily Kandinsky’s Artworks and Life

Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract contemporary art, used the compelling interrelationship between colors and shape to generate an aesthetic sensation that captivated the public’s eye, hearing, and feelings. He thought that absolute abstraction allowed for meaningful, sublime articulation and that imitating from the environment merely hampered this approach. He invented a graphical vernacular that was only superficially linked to the outer world but conveyed much about the artist’s internal world. He was highly driven to produce work that transmitted a unifying feeling of spirit.

Kandinsky’s visual language evolved through three stages, beginning with his early, realistic canvases and their heavenly meaning, progressing to his euphoric and dramatic creations, and finally to his late, geometrical, and biomorphic flat surfaces of pigment.

Kandinsky’s paintings and beliefs influenced numerous decades of painters, from his Bauhaus pupils through the Abstract Expressionists following WWII. Kandinsky’s paintings were, above all, immensely spiritual. He aimed to communicate deep mysticism and the profundity of human feeling through a global visual medium of geometric shapes and hues that crossed sociocultural borders.

Kandinsky’s abstract art was seen as the optimum visual method for expressing the creator’s “inner imperative” and conveying universal human feelings and concepts.

He saw himself as a messenger whose job was to communicate this concept with the rest of the world in order to improve society. Kandinsky considered music to be the most transcending type of non-objective creativity since musicians could conjure pictures in the imaginations of listeners just by using sounds. He aimed to create equally object-free, emotionally complex artworks that referred to noises and feelings via unification of sense.

Our List of Important Wassily Kandinsky Paintings

Kandinsky’s abstract artworks such as his abstract circle paintings might be his most well-known, but it was not the first style he painted in. Some of his earlier works display a more traditional approach. Let us take a deeper look at the Wassily Kandinsky artworks that were important pieces in his artistic journey.

The Blue Rider (1903)

| Date Completed | 1903 |

| Medium | Oil on Card |

| Dimensions | 69cm x 55 cm |

| Current Location | Private Collection |

Kandinsky, the only child of a tea trader, was born in Moscow in 1866. When his folks separated, he was forced to reside with an aunt, and it was during his time there that he encountered the power of color. At university, he chose to study Finance and Law, and he passed his exams “without difficulty.”

After witnessing one of Monet’s Haystacks works soon after he wedded his cousin, he was confronted with the choice of becoming a lecturer or launching a career in the arts. He chose to study painting, so the 32-year-old traveled to Munich, Germany, in 1896. It features a horseman wearing a blue cape racing through a field on a pale steed, with woodland in the backdrop.

The uncertainty of the man on horseback’s shape, depicted in a mixture of hues that almost melt together, foreshadows his involvement in abstraction.

The steed and rider motif resurfaced in several of his subsequent paintings. This pattern represented Kandinsky’s rejection of established aesthetic ideals as well as the prospects for a refined, more spiritual existence via art. The picture itself is unimpressive, but it marked a significant turning point in Kandinsky’s aesthetic movement from impressionism to contemporary abstract art, of which he was a forerunner. It was one of his final impressionist paintings and has early indications of the style that would become his specialty. Blue, in particular, was to have a profound meaning for the painter.

Another important aspect of the piece is that it shares its German term with the name of Kandinsky’s organization of progressive painters, which produced a periodical journal and organized exhibits of their works in 1911.

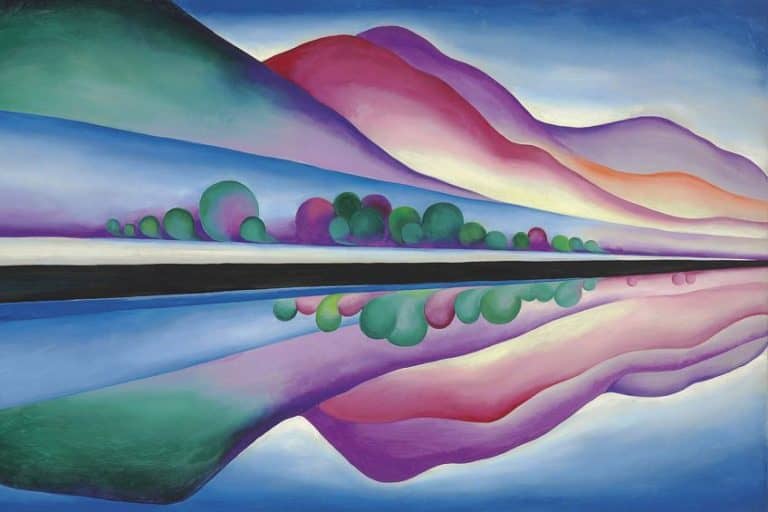

Blue Mountain (1909)

| Date Completed | 1909 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 107 cm x 96 cm |

| Current Location | The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum of Art |

The effect of the Fauves on Kandinsky’s color pallet is visible in this piece, as he twisted hues and drifted away from the organic environment. He displayed a vivid blue mountain bordered along either end by a yellow and red bush. Riders on horseback gallop through the area in the forefront. The Book of Revelation by Saint John became an important textual reference for Kandinsky’s painting at this point in his career, and the riders represent the four horsemen of the apocalypse.

Although the horsemen depict the apocalypse’s tremendous destruction, they also represent the possibility of salvation later.

Kandinsky’s brilliant color and dynamic brushwork convey a feeling of optimism rather than sorrow to the spectator. Furthermore, the vibrant colors and black contours go back to his appreciation of Russian folk art. These inspirations would continue to affect Kandinsky’s approach for the remainder of his career, with vivid colors commanding both realistic and non-objective works. Kandinsky moved away from realistic and largely symbolic art and sought absolute abstraction.

In this painting, the forms are clearly modeled from their visible presence in the outer environment, and his abstractions advanced only when Kandinsky perfected his beliefs about art.

Composition IV (1911)

| Date Completed | 1911 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 159 cm x 250 cm |

| Current Location | Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf |

Composition IV was completed in 1911 as a portion of a ten-part series. Kandinsky employed bright, opposing colors to create an aesthetic, metaphysical, and psychological impression on the viewer. In the upper left corner of the image, two Invaders wield cutlasses. On the right, five Invaders wielding spears and one wielding a sword stand against a blue hillside with a building atop it.

A rainbow in the center-left of the image represents a footbridge. Black lines highlight the yellows and shades of red. Kazimir Malevich’s art featured common ideas. Sharp lines of various thicknesses juxtapose with the gentler colors used in the painting, and two vertical lines appear to partition the arrangement.

The audience’s attention is quickly attracted to the blue spot in a backdrop that is predominantly colored in soft pastels.

Colors blend harmoniously, as do lines and forms, alluding to the coming harmony and redemption. Kandinsky was greatly influenced by the use of color in Monet’s artwork Haystacks and the orchestral composition of Richard Wagner’s Lohengrin. He was also intrigued with Madame Blavatsky’s metaphysical notions of occultism. In Composition IV, he employed a jumble of chaotic forms and colors to communicate spiritual and emotional themes. Except for his works Riding Couple (1906) and Sunday, Old Russia (1904), Kandinsky never included human beings in his work.

The use of color in both works takes precedence over the portrayal of the subject material.

Composition VII (1913)

| Date Completed | 1913 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 190 cm x 275 cm |

| Current Location | Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow |

Composition VII, often regarded as Kandinsky’s zenith of pre-World War I success, demonstrates the creator’s renunciation of graphic presentation through a whirling maelstrom of colors and patterns. Kandinsky’s conviction that artwork might conjure sounds in the same way that music-evoked particular hues and patterns are exemplified by the theatrical and chaotic swirling of shapes around the painting. Even the name, Composition VII, reflected his ambition infusing the melodic and the aesthetic, emphasizing Kandinsky’s non-representational approach in this piece.

Kandinsky erased conventional allusions to perspective and exposed bare the many stylized characters as the diverse hues and patterns swirl around one another in order to reveal underlying concepts and feelings shared by all civilizations and observers.

Throughout the 1910s, Kandinsky was concerned with the concept of Armageddon and salvation, and he officially related the spinning arrangement of the artwork to the concept of the cyclical cycles of annihilation and rescue. Despite the artwork’s apparent lack of objectivity, Kandinsky included various symbolic connections. Kandinsky created glyphs of vessels with oars, hills, and individuals among the many shapes that comprised his visual lexicon.

He did not wish for audiences to take these emblems literally, instead infusing his works with many allusions to the Last Judgment, the Floods, and the Paradise of Eden, presumably simultaneously.

Moscow I (Red Square) (1916)

| Date Completed | 1916 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 49 cm x 51 cm |

| Current Location | The State Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow |

Initially, the transfer to Moscow in 1914 triggered a period of despair, and Kandinsky barely created anything during his first year there. In a correspondence to his close colleague, Munter, when he managed to grab up his brush again in 1916, he declared his wish to paint a painting of Moscow. Despite continuing to perfect his abstraction, he depicted the city’s landmarks and caught the essence of the city in this artwork. Moscow I (Red Square) is a unique urban environment that is far from attempting to replicate the square’s appearance.

Kandinsky depicts the heart of Moscow, one of his favorite locations. He is pivoting in the midst of the plaza and showcasing its key landmarks, partly employing a future manner of expressing the flow of shapes.

The artist described his favorite time of day as “melting all of Moscow reduced to a specific point that, like a crazy tuba, begins all of the soul and all of the spirit humming.” This moment of dusk is “the concluding chord of a concerto that brings every hue to the pinnacle of existence and, like the crescendo of a great symphony, is both forced and permitted to cry out by Moscow.”

“The city signifies dualism, intricacy, and a greater amount of motion, conflict, and disarray of various aesthetic parts… This inner and exterior Moscow, I regard to be the launching point of my starvation. “Moscow is a graphic tuning fork for me,” he said.

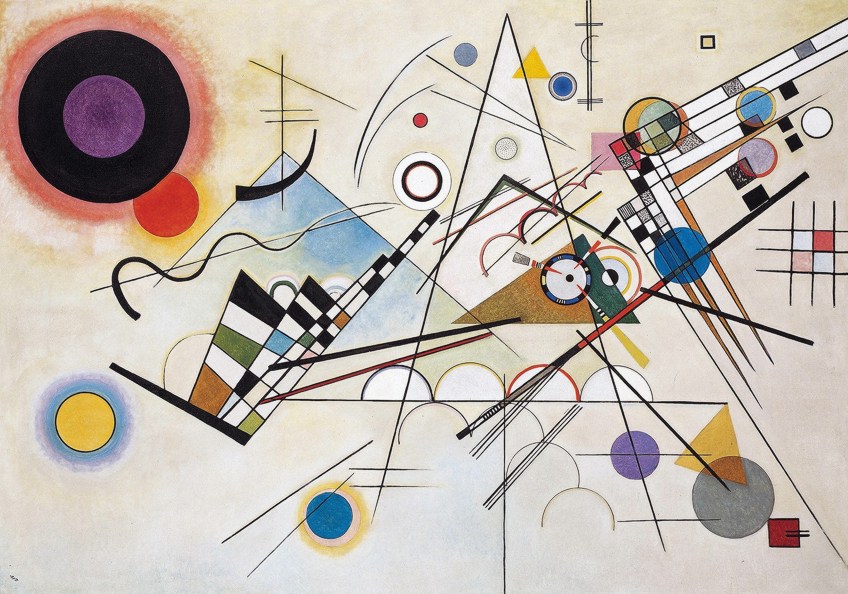

Composition VIII (1923)

| Date Completed | 1923 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 140 cm x 201 cm |

| Current Location | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum |

The picture is made up of a multitude of geometric forms, colors, straight and curving lines placed on a creamy backdrop that blends into patches of pastel blue at various spots. The employment of rings, squares, rectangular shapes, arcs, pyramids, and other geometric forms in the work reflects the artist’s conviction in the metaphysical characteristics of geometric forms, while the colors on exhibit are selected for their psychological effect.

Kandinsky, who had been captivated with color since a young age and believed it had mystical characteristics, intended to investigate an interrelationship between noise and color that would enable an artist to create a work in the same way as musicians construct songs.

Kandinsky had migrated from the budding Soviet Union to the Weimar Republic at the time the picture was made, a period that is known as the Bauhaus period, due to rising constraints on creative expression under the Marxist-Leninist governmental system. The years passed in the old Russian Empire and its succeeding state, mostly spent renovating museums and advocating his creative views, had not been fruitful in respect of artistic creation, but the painter would exit from this phase of his life re-energized and ready to get back to producing.

1920s Germany, in which this painting was produced, was one of the most progressive periods and places in Europe, having made the transition from an aristocracy to a true democracy, and offered a healthy atmosphere for the avant-garde movement that so motivated Kandinsky during his early years.

The picture is now on exhibit at the Guggenheim Museum in New York.

On White II (1923)

| Date Completed | 1923 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 105 cm x 98 cm |

| Current Location | Georges Pompidou Center, Paris |

Kandinsky employed a variety of geometric forms and lines in a colorful and riotous modern presentation, inspiring many painters to emulate him. On White II may be seen in the Georges Pompidou Centre in Paris, France. The color white dominates this picture, including the backdrop, as the title says. White was utilized by Kandinsky to signify life, calm, and stillness.

The artist’s enthusiasm for the free outpouring of inner feelings is reflected in the bulk of the geometric designs, which are displayed in a range of colors.

Bold, spiky barbs in black pierce the spectrum of forms and colors, suggesting non-existence and mortality. The intricacy of a musical arrangement can be likened to the complex and perhaps mesmerizing display of forms and colors. Kandinsky, one of the pioneers of abstract, contemporary painting, employed the graphic interrelationship between color, form, and shape to excite the audience’s intellect and open the door to profound spiritual expression.

Art, according to Kandinsky, was a method of communicating a deep feeling of soul and human feeling via the use of highly abstract shapes that transcended all traditional bounds.

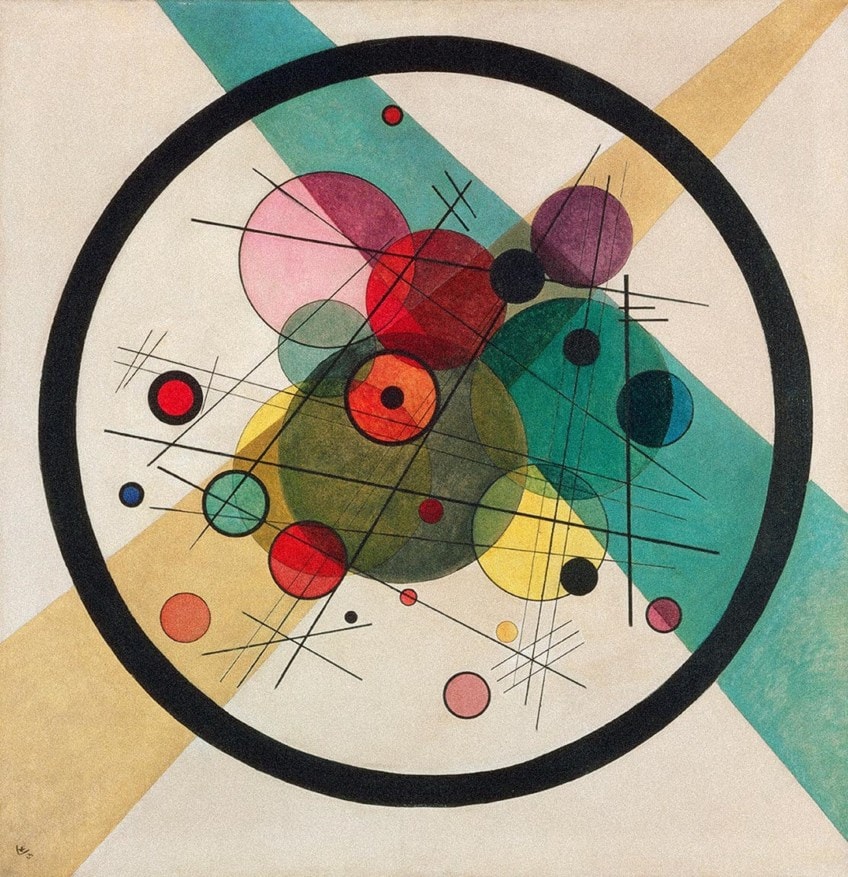

Circles in a Circle (1923)

| Date Completed | 1923 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 98 cm x 95 cm |

| Current Location | Philadelphia Museum of Art |

Synesthesia is thought to have developed in Kandinsky. This showed itself for him through the combination of sight and hearing. He is also considered to have been a profoundly intellectual person and painter, with his work frequently exploring the equilibrium of the cosmos and the notion of spirituality.

Despite the fact that Kandinsky painted numerous abstract circle paintings, he utilized the form of a triangle to represent humanity’s enlightenment and ascension.

The colors and patterns of Circles in a Circle create a disorienting impression. The inner elements appear to buzz with vitality or float to the top of some mysterious pool, since they are surrounded by a thick black outermost ring. The art has a natural element – something like stars or sunbeams – but also a visual intensity that stems from his experience lecturing at the Bauhaus from 1922 to 1933.

Others have examined this complex arrangement from a metaphorical standpoint, delving into the interpretations of the hues and the precise number of circles and lines.

Several Circles (1926)

| Date Completed | 1926 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 140 cm x 140 cm |

| Current Location | Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum |

Kandinsky created this abstract circle painting in his sixties, and it exemplifies his continuous quest for the optimum expression of emotional manifestation in art. This famous circle artwork, produced as part of his exploration with a linear painting approach, demonstrates his fascination with the shape of the circle.

“The circle,” Kandinsky argued, “is the unification of the strongest opponents. It blends the circular and erratic in a single shape that is balanced. It is the most obvious of the three major shapes to indicate the fourth dimension.”

In this piece, he focused on the circle’s various interpretive opportunities to create a feeling of emotional and spiritual equilibrium. Each circle’s varied size and vivid colors pop up from the painting and are tempered by Kandinsky’s delicate dissonances of scale and color.

The circular shapes’ fluid motion reflects their inclusivity – from planets in the galaxy to droplets of dew; the circle is a shape essential to existence.

Composition X (1939)

| Date Completed | 1939 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 130 cm x 195 cm |

| Current Location | Kunstsammlung Nordrhein-Westfalen, Düsseldorf |

Kandinsky believed that a real artist who creates art out of “interior necessity” lives at the top of an ascending pyramid. This ascending pyramid is probing and moving forward. What was strange or unthinkable yesterday is now ordinary; what is avant-garde now (and only comprehended by a select few) will be general information someday. The modern painter stands alone at the top of the pyramid, discovering fresh breakthroughs and bringing in the realities of the future.

Kandinsky was aware of current technological breakthroughs as well as the advancements of contemporary artists who had added to profoundly novel methods of seeing and learning about the world.

Composition X and subsequent works are primarily focused on generating a spiritual connection in both the observer and the creator. Kandinsky, like in this picture of armageddon by water (Composition X), puts the observer in the perspective of encountering these great narratives by interpreting them into modern terms with a feeling of anguish, flurry, confusion, and urgency.

Within the confines of words and visuals, this spiritual connection of observer, artwork, and prophet may be articulated. Kandinsky frequently compared the painting of hues and images on canvas to the arrangement of wonderful music, and as a result, many of his works were titled variations of Composition X.

His metaphor of artwork is a piece of music centered around the keyboard, with the eyes representing the hammers, the color representing the keys, and the soul representing the musical instruments and strings. Kandinsky’s compositions, like music, are not just muddles of tones. They were deliberately placed musical parts that were exactly calibrated to elicit the greatest aesthetic and psychological reaction from the spectator.

Wassily Kandinsky’s paintings are among the most significant in the field of abstract art. Kandinsky’s abstract artworks reflected his idea that “objects hurt pictures,” therefore he experimented with forms and colors to evoke mysticism and human emotion. Kandinsky’s paintings conveyed their own visual lexicon, which transcended material reality to express the human predicament. Wassily Kandinsky’s portraits and iconic circle paintings established him as one of modern art’s most significant figures.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Was Wassily Kandinsky Known For?

In the early 20th century, Wassily Kandinsky revolutionized abstract art. He maintained that geometric shapes, curves, and hues might convey the artist’s interior existence. This approach was obvious in his own dramatic works, which were frequently influenced by music. Kandinsky’s works now fetch tens of millions of dollars at auction and are housed in several museums around the world.

What Is Abstract Art?

Abstract art employs an optical vocabulary of form, shape, hue, and contour to produce a creation that can exist independently of visual cues in the environment. From the Renaissance through the 19th century, Western art was grounded by the principle of viewpoint and an endeavor to replicate an impression of apparent reality. By the 19th century, numerous painters felt compelled to produce a new type of art that would reflect the profound changes occurring in industry, physics, and thought.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Kandinsky Paintings – Exploring the Best Wassily Kandinsky Artworks.” Art in Context. November 9, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/kandinsky-paintings/

Meyer, I. (2021, 9 November). Kandinsky Paintings – Exploring the Best Wassily Kandinsky Artworks. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/kandinsky-paintings/

Meyer, Isabella. “Kandinsky Paintings – Exploring the Best Wassily Kandinsky Artworks.” Art in Context, November 9, 2021. https://artincontext.org/kandinsky-paintings/.