Henri Cartier-Bresson – A Look at This Photographer’s Greatest Works

The pioneer of street photography and master of candid photography, Henri Cartier-Bresson was a French humanist photographer and artist who lived life on his own terms. Cartier-Bresson is most famed for his book The Decisive Moment and his involvement in Magnum Photos. For Henri Cartier-Bresson, photographs captured distinct moments of life and held them for eternity.

Table of Contents

Who Was Henri Cartier-Bresson?

From a young age, Cartier-Bresson was interested in photography and art. Throughout his years at school, Cartier-Bresson read widely, developing his passion for literature, writing, and art. Interestingly enough, this famed and accredited photographer did not like to be photographed.

Childhood and Early Education

Born in 1908 in Chanteloup-en-Brie, just outside of Paris, Henri Cartier-Bresson had a bourgeois entry into the world. Cartier-Bresson’s parents were involved in the textile manufacturing process and hoped he would continue in the family line. From his early rejection of his father’s dreams for him, it was clear that Cartier-Bresson would live an extraordinary life.

Young Henri attended a Catholic school, Ecole Fenelon, which aimed to prepare children for Lycee Condorcet, one of the oldest and most prestigious high schools in Paris. During his schooling, Miss Kitty, an English governess, gave Cartier-Bresson a competence in and love of the English language.

Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Introduction to Art

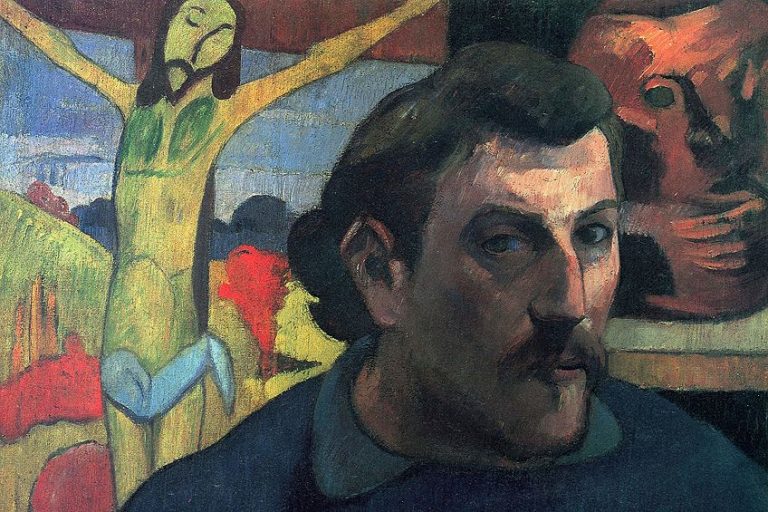

Henri was first introduced to oil painting by his uncle Louis. Sadly, these painting lessons were short-lived as Louis died in the First World War. After his school education, Cartier-Bresson pursued his interest in art and attended the Lhote Academy in 1927, which was the studio of Andre Lhote. Lhote was a sculptor and painter in the Cubist movement who aimed to join classical art forms with the Cubist approach to reality.

With Lhote, Cartier-Bresson studied artists from contemporary and classical styles. During his studies, Cartier-Bresson also read widely. Books by Freud, Dostoevsky, Marx, Engels, Proust, Joyce, and Rimbaud, to name but a few, inspired his artistic approach. Cartier-Bresson was also a student of Jaques Emile Blanche, a famed society portrait artist.

Cartier-Bresson found a lot of photographic inspiration in the Surrealist art movement, which sprung up in 1924. Around this time, Cartier-Bresson spent a great deal of time at the Cafe Cyrano, which was a popular spot among the proponents of Surrealism. It was the focus on the subconscious and unpredictable and often unintended meanings that lay beneath works of art that drew Cartier-Bresson towards Surrealism.

It was within the stormy political and cultural atmosphere that Cartier-Bresson developed his artistic maturity. Cartier-Bresson’s approach to his work reflected the cultural dissatisfaction around him. Feeling that he could not adequately express the concepts that inspired him, Cartier-Bresson destroyed many of his earliest paintings.

Photographic Career: How Cartier-Bresson Pioneered Photographic and Candid Journalism

Although Cartier-Bresson’s artistic education was in painting, he had demonstrated a fascination with photography since using a Box Brownie camera to capture holiday pictures as a boy. During his early adult years, Cartier-Bresson became increasingly involved in the world of surrealist photography, filmmaking, and photojournalism. For Henri Cartier-Bresson, photos provided insights into the world that went beyond the surface level.

Transitioning: Moving from Painting to Photography

Cartier-Bresson studied English, literature, and art at the University of Cambridge between 1928 and 1929. It was in the French army, however, that Cartier-Bresson could actively pursue photography. In 1930, Cartier-Bresson joined the French army via conscription. While stationed near Paris at Le Bourget, Cartier-Bresson met Harry Crosby, an American expatriate. Crosby shared Cartier-Bresson’s passion for photography and gifted Cartier-Bresson his first camera. Crosby and Cartier-Bresson became firm friends, and Cartier-Bresson entered into an allowed affair with Crosby’s wife, Caresse Crosby. Sadly, Harry Crosby committed suicide soon after they met, and Cartier-Bresson’s relationship with Caresse Crosby ended two years later in 1931.

After his heartbreak, Cartier-Bresson spent almost a year in the Ivory Coast, where he documented his travels with a miniature camera. On this journey, Cartier-Bresson contracted blackwater fever, forcing his return to France. Although only seven photographs survived this trip, he was impressed with the ease with which the small camera could capture impressions that lasted only moments.

A photograph titled Three Boys at Lake Tanganyika captured by Martin Munkasci, a Hungarian photojournalist, impressed upon Cartier-Bresson the ability of a photograph to preserve a single moment for eternity.

On his return to France, Cartier-Bresson purchased his first Leica 35-mm camera. The Leica remained his camera of choice throughout his career, thanks to its spontaneity and discretion. Anonymity was essential to Cartier-Bresson because it allowed him to overcome the awkward and unnatural behavior that accompanies people’s awareness of being photographed. Cartier-Bresson’s Leica, with chrome parts covered in black tape and often hidden beneath a handkerchief, allowed Cartier-Bresson access to the intimate and fleeting moments of life around him.

In 1933, Cartier-Bresson held his first photographic exhibition in New York at the Julien Levy Gallery, where he presented photographs from his travels throughout Brussels, Prague, Madrid, Budapest, Warsaw, and Berlin. In 1934, Cartier-Bresson shared an exhibition in Mexico with fellow photographer Manuel Alvarez Bravo. Cartier-Bresson met David Syzmin, a Polish photographer and intellectual, in the same year. These two men would go on to be firm friends and collaborators. It was also through Syzmin that Cartier-Bresson met Hungarian photographer Endre Friedman. Friedman later changed his name to Robert Capa, and Syzmin also changed his name to Seymour.

Experiments in Filmmaking

While in New York, Cartier-Bresson’s photographs were first published in Harper’s Bazaar. He also met Paul Strand, a photographer who did the camerawork for The Plow That Broke the Plains, a documentary from the Depression era. Sparking his interest in filmmaking, Cartier-Bresson worked as an assistant to Jean Renoir.

Renoir was a renowned director who made Cartier-Bresson act in two of his films, La Regle du jeu (1939) and Partie de Campagne (1936),to experience what it was like to be on the other side of the camera. Finally, Renoir allowed Cartier-Bresson to help create a film about the 200 families (his own included) who controlled France. This film was created on the behalf of the Communist Party of France. Cartier-Bresson was involved in another political, anti-fascist film which he co-directed with Herbert Kline during the Spanish civil war.

Investing in Photojournalism

Cartier-Bresson’s big break with his photojournalism came in 1937, when his photographic coverage of Queen Elizabeth and Kind George VI’s Coronations graced the pages of Regards. These photographs capture the adoring subjects lining the streets while completely neglecting to capture the King or Queen. Cartier-Bresson was hesitant to divulge his family name, so the photo credit was simply ‘Cartier.’

Henri Cartier-Bresson married Ratna Mohini, a Javanese dancer, in 1937, and the two lived in a servant’s flat on the fourth floor in Paris. Cartier-Bresson developed his film in the bathroom when he worked for Ce Soir, an evening paper by the French Communists, between 1937 and 1939.

Back to War with a Camera

Cartier-Bresson returned to the French army as a Corporal in the photo and film unit when the Second World War broke out in September of 1939. After being captured by the Germans in 1940, Cartier-Bresson spent a total of 35 months doing hard labor as a prisoner of war of the Nazis.

Two failed escape attempts landed him in solitary confinement. His third attempt was successful, and he spent some time in Touraine at a farm while waiting for falsified papers to return to France. On his return to France, Cartier-Bresson worked underground to document the occupation and liberation of France. Towards the end of the war, Cartier-Bresson made Le Retour, a documentary about displaced persons and former prisoners returning to France.

Rumors that Henri Cartier-Bresson had died in the war spread to America towards the end of the war. These rumors and his documentary inspired the Museum of Modern Art to hold a retrospective exhibition of his work in 1947. This same year, his first book, The Photographs of Henri Cartier-Bresson, was published.

The Start of New Ventures

Following his experience in the Second World War, Cartier-Bresson continued to be a pioneer in the world of photojournalism. Founding a collective photography agency and publishing another book of photographs, Cartier-Bresson made a name for himself internationally.

Magnum Photos: In the Service of Humanity

Magnum Photos, a cooperative pictures agency, was founded in 1947 by its members Cartier-Bresson, David Seymour, Robert Capa, George Rodger, and William Vandivert. Magnum had two offices, one in Paris that was managed by Maria Eisner, and one in New York managed by Rita Vandivert. The photographers in Magnum split assignments among themselves.

Seymour covered European assignments thanks to his mastery of several European languages. Vandivert left the magazine Life and worked in America, while Rodger, who had also quit Life, covered the Middle East and Africa. Capa worked anywhere that there was an assignment while Cartier-Bresson took on photographic assignments in China and India.

It was during his time with Magnum that Cartier-Bresson attained international recognition. In 1948, Gandhi’s funeral service was captured by Cartier-Bresson, and a year later, he documented the final stages of the Civil War in China. In Beijing, Cartier-Bresson captured the last imperial eunuchs as the city fell to the communists. Working alongside Sam Tata, another photojournalist when in Shanghai, Cartier-Bresson documented the final six months of the Kuomintang administration and the first half a year of the Maoist People’s Republic.

Following his work in China, Henri Cartier-Bresson traveled to Indonesia. Here, Cartier-Bresson captured critical moments of the fight for independence from Dutch Imperialism. Cartier-Bresson progressed to India in 1950, where he visited and photographed Sri Ramana Ashram and the final days of Ramana Maharishi. Sri Aurobindo and Sri Aurobindo Ashram in Pondicherry was also photographed by Cartier-Bresson a few days later.

The mission of the Magnum photographic collective was to capture and portray the throbbing heart of the times. Cartier-Bresson and the other Magnum photographers believed in using photography for the assistance of humanity. Some of the most notable initial projects compiled by Magnum are The Child Generation, People Live Everywhere, Women of the World, and Youth of the World.

Images on the Sly: Finding the Decisive Moment

Cartier-Bresson published his book titled in English, The Decisive Moment, although the French title actually translates to mean Images on the Sly. Both titles express the nature of the collection of 126 photos from the Western and Eastern worlds. The French title perfectly encapsulates Cartier-Bresson’s technique of capturing photographs where the subjects were unaware. He believed this to be the most accurate depiction of the world and the people in it.

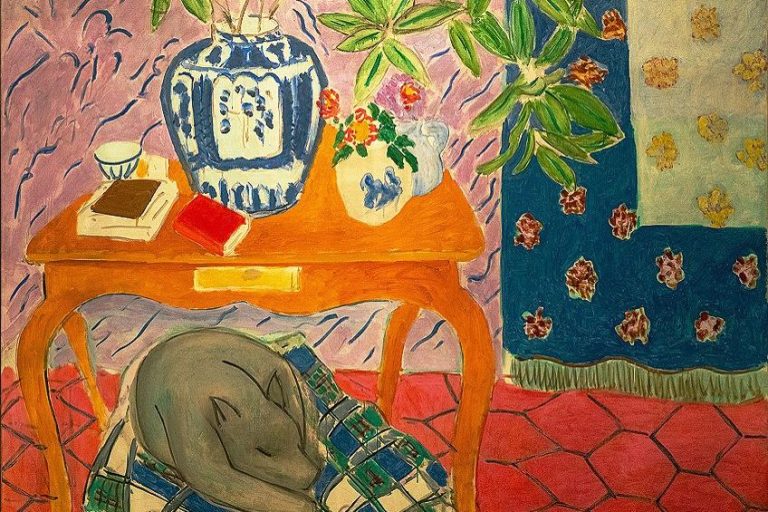

The English title also wonderfully captures Cartier-Bresson’s belief that photography as an art form, is most able to capture the split-second moments of significance where life offers up the most perfect compositions of people and places. A drawing by Henri Matisse adorns the book’s cover, and Henri Cartier-Bresson quotes Cardinal de Retz in the preface.

Many present Cartier-Bresson’s photograph Rue Mouffetard, Paris, as evidence of his unique ability to capture the decisive moments of which he speaks. In 1955, following the release of his book, Cartier-Bresson held his first French exhibition at the Louvre.

The Later Life and Career of Henri Cartier-Bresson

In his 40 years and more as a photojournalist, Cartier-Bresson traveled to many places around the world. He did not visit quickly either, preferring to immerse himself thoroughly in the culture of each place. When Cartier-Bresson visited the Soviet Union shortly after the war, he was the first photographer from the west to do so.

In 1962, Cartier-Bresson made a 20-day trip to Sardinia in partnership with Vogue, where he stayed for a while with a friend, Constantino Nivola. While in Sardinia, Cartier-Bresson visited Oliena, Orosei, San Leonardo di Siete Fuentes, Orgosolo Mamoiada Desulo, Cala Gonone, Cagliari, and Orani. Four years later, in 1966, Cartier-Bresson stepped back as a prominent member of Magnum. To Henri Cartier-Bresson, portraits and landscapes became more interesting.

Cartier-Bresson began to shift his focus towards producing motion pictures in the late 1960s, believing that television was replacing printed photography. Cartier-Bresson did not, however, hold the camera himself during the production of these movies.

Henri Cartier-Bresson divorced his wife of 30 years in 1967, and a year later, he began to drift away from photography as his artistic medium of choice. In 1970, Henri married Martine Franck, a Magnum photographer, and the two had a daughter in 1972. Cartier-Bresson thought he had reached the end of what he could express through photography and returned to his love of painting and drawing in the early 70s. Cartier-Bresson is said to have locked his camera in a safe, and he only took it out for the sporadic private portrait.

Henri Cartier-Bresson exhibited his paintings and pen, ink, and pencil drawings for the first time in 1975 at the Carlton Gallery, New York. Cartier-Bresson also published several books in the 1970s. Cartier-Bresson’s France was published in 1971, followed by The Face of Asia in 1972, and About Russia in 1974.

The Ongoing Legacy of Henri Cartier-Bresson

Cartier-Bresson died in 2004 in his home country of France. After spending over 40 years taking photographs of some of the most momentous and most trivial events of the 20th Century, Cartier-Bresson’s legacy is preserved by the Henri Cartier-Bresson Foundation in Paris. There are very few Henri Cartier-Bresson portraits in existence as he preferred to be behind the camera.

Recommended Book Collections of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s Decisive Moments

We have gathered together a short selection of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s most well-known collections of photographs that you can explore.

Cartier-Bresson’s France

Authored by Henri Cartier-Bresson with commentary by Francois Nourissier, this is a beautiful collection of photographs captured in and around France between 1968 and 1969. Nourissier’s writing is humorous and knowledgeable, providing a nuanced representation of the famed photographer with Henri Cartier-Bresson quotes. Unfortunately, the book is no longer in print, but copies are still available for purchase. We cannot recommend this photography collection enough for those interested in gaining a well-rounded impression of Cartier-Bresson.

- Witty and knowledgeable commentary by Francois Nourissier

- Exquisite collection of photographs in and around France

- Nuanced view of Henri Cartier-Bresson

The Face of Asia

Originally published in 1972, this stunning collection of photographs provides in-depth documentation of Cartier-Bresson’s time in the East. This collection is separated into five distinct chapters. One chapter documents the great religions of India, including Buddhism, Hinduism, and Islam. Another chapter captures China and Japan before, during, and after the revolution. The book also includes a chapter on the ancient civilizations of Iraq, Uzbekistan, Iran, and Turkey. We recommend this photographic collection for anybody interested in the work of Cartier-Bresson or Asian culture.

- In-depth documentation of Cartier-Bresson's time in the East

- Informative about Asian history and culture

- Chapters cover religion, revolution, ancient civilisations, and more

About Russia

Cartier-Bresson was one of the first Western photographers to be allowed free access to post-war Russia. This book beautifully presents the photographs he captured during this time. This book too is divided into four parts, covering Estonia, the Federal Republic of Russia, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. If you want a rare view of city and country life in Soviet Russia, we cannot recommend this book enough.

- Four sections covering Russia, Estonia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia

- Rare view of both city and country life in Soviet Russia

- Unmissable and profound documentation of post-war Russia

Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “Henri Cartier-Bresson – A Look at This Photographer’s Greatest Works.” Art in Context. January 15, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/henri-cartier-bresson/

Anthony, J. (2021, 15 January). Henri Cartier-Bresson – A Look at This Photographer’s Greatest Works. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/henri-cartier-bresson/

Anthony, Jordan. “Henri Cartier-Bresson – A Look at This Photographer’s Greatest Works.” Art in Context, January 15, 2021. https://artincontext.org/henri-cartier-bresson/.