Leonora Carrington – The Pioneer of Feminist Surrealism

Pioneer of feminist Surrealism and founding member of the Mexican Women’s Liberation Movement, Leonora Carrington is an artist and novelist who redefined female imagery and symbolism within the Surrealist movement. Carrington was born in England but spent most of her life in Mexico, where she explored materials, including mixed-media sculpture, oil painting, and traditional cast iron and bronze sculpture. Leonora Carrington worked closely with other Surrealist artists, including Max Ernst and Remedios Varo.

A Leonora Carrington Biography

The life of Leonora Carrington, surrealist painter, was nothing short of surreal. Born into a wealthy British family, Carrington rebelled against the status quo from a young age. Her interest in the surreal also began at a young age, and she fled her arranged life to devote herself to her art. Carrington’s life was full of surreal experiences, from fleeing the Nazis in France to spending time committed in mental institutions. Her art is as daring, revolutionary, and bizarre as her life.

The Creation of Leonora Carrington

Carrington has famously described her entry into this world not as a birth but as a creation. The writer described in flowing verse how she came about on a melancholy day. Her mother, she said, lay around feeling undesirable and bloated with cold pheasant, pureed oyster, and rich chocolate truffles.

As her mother lay down on a marvelous machine designed to extract copious amounts of semen from various animals – ducks, bats, pigs, urchins, and cows – the machine brought her to overwhelming orgasm, turning her entire bloated and miserable body upside down and inside out. It was from this bizarre communion of machine, animal, and human that Leonora Carrington emerged.

This creation story encompasses all the elements of Carrington’s rich life and art. The sense of fancy, the fascination with profane and otherworldly bodies – be they animal, human, or machine – and the indelicate decadence of Carrington’s inner world all play out in this creation narrative. The butt of this creation story is her incurably dull and repressive Anglo-Irish origins, which could not be further removed from this twisted tale.

Carrington was born into an affluent home in England in 1917. Carrington’s mother was Irish, and her English father was a prosperous manufacturer of textiles. In the manner of traditions, Carrington received her education from tutors, governesses, and nuns. Her rebellious behavior was clear from a young age and caused her expulsion from two separate schools.

Even as a young girl, Carrington rejected the social expectations of her upper-class status. She recoiled at the strict rules of the Roman Catholic boarding schools and tired easily of the endless streams of debutante balls. Around this time, Carrington attended the St Mary’s Convent school in Ascot.

Leonora Carrington and Surrealism

Carrington first grasped onto Surrealism after seeing her first Surrealist painting at the age of ten when she visited the Parisian Left Bank gallery. She received little support from her father for her artistic career, but her mother was more encouraging. Despite the lack of familial support, Carrington pursued her artistic career.

In 1935, Carrington spent time studying at the Chelsea School of Art. She did not stay there long however, moving to the Ozenfant Academy of Fine Arts. A year later, her mother gave her the book Surrealism, written by Herbert Read. Carrington went to London to visit her first International Surrealist Exhibition when she was 19 years old.

Max Ernst’s work, in particular, caught her attention. Carrington felt particularly drawn to Two Children are Threatened by a Nightingale (1924). The following year, Carrington met Ernst, and this marked the beginning of a close, personal, and professional relationship between the two.

Leonora Carrington and Max Ernst

Roughly six months after Carrington first saw Ernst’s work at the first International Surrealist Exhibition, the two met in London. Carrington was studying at the Ozenfant Academy, and Ernst was in London for the exhibition. Ursula Blackwell, Carrington’s classmate, invited both Ernst and Carrington over to dinner, and they fell almost instantly in love. Shortly after the party, the two artists left for Paris together, where Ernst divorced his wife.

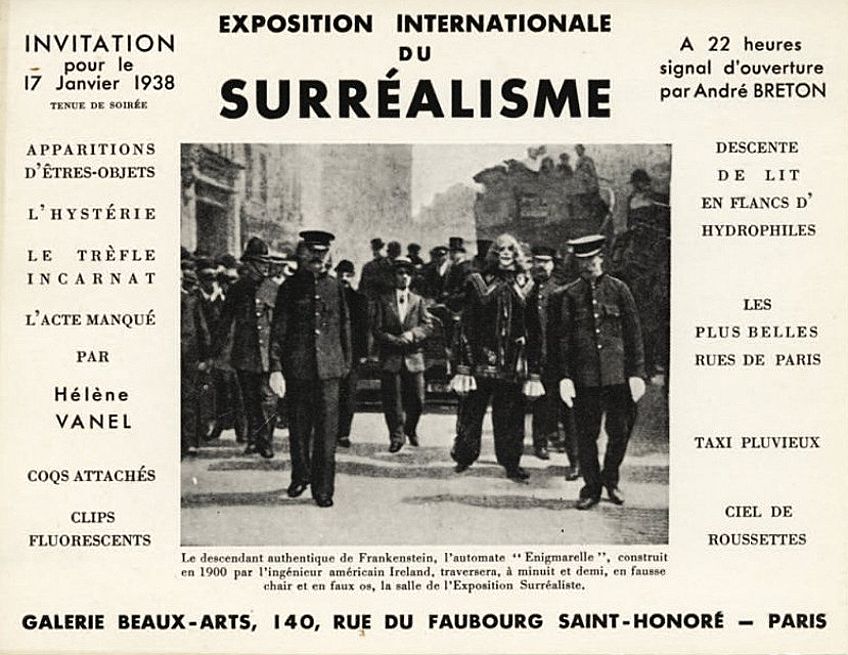

While in Paris, Carrington met Yves Tanguy, Andre Breton, and Leonor Fini. Carrington, Surrealist painter, also participated in the Parisian 1938 Exposition Internationale du Surrealisme. In addition, she exhibited her works in Amsterdam at a Surrealist exhibition, which firmly set her position as a Surrealist artist. Despite this, Carrington did not see herself as a Surrealist.

While she did agree with many Surrealist values, including the contempt for bourgeois dogmas, Carrington remained autonomous in her artistic expression. Her work extends far beyond the egocentric environment of Surrealist orthodoxy, and Carrington never ascribed to using common Surrealist motifs in her work.

Carrington and Ernst moved to Saint Martin d’Ardeche in the south of France, where they settled into a collaboration and relationship. The couple decorated their Saint Martin house with sculptures of each of their guardian animals. Carrington’s creation was a horse head in plaster, while Ernst sculpted his birds.

Carrington was now well into her artistic career as a Surrealist painter, having painted The Inn of the Dawn Horse between 1937 and 1938. In 1939, Carrington painted the Portrait of Max Ernst, which captures a sense of relational ambivalence. The couple frequently hosted gatherings with their Surrealist circle, but Carrington remained firmly on the movement’s periphery.

The members of the Surrealist movement had an ambivalent attitude towards women. The Freudian idea that the psyche of women was mystical, erotic, and unrestrained was the opinion of many Surrealists, including Andre Breton. As a result, many female surrealist artists were portrayed as the femme enfant, or the woman child, who were little more than muses for male artists.

Carrington was not one to take on any submissive role, and she is known to have said that she did not have the time to be a muse for anyone because she was too occupied with fighting her family and becoming an artist in her own right.

Fleeing the Nazis and Fighting Mental Health

When the Second World War broke out in September 1939, Ernst was arrested by the French because he was German and considered an enemy alien. Luckily, following the intervention of several of his friends, including Varian Fry and Paul Eluard, Ernst was released from custody. His freedom did not last long, however, and he was arrested again. This time Ernst was arrested by the Gestapo, who found his art degenerate by Nazi standards. After he managed to escape, Ernst left for America.

Left alone in France as the war descended around her, Carrington’s mental state began to shake. Carrington became increasingly paranoid, stopped eating, cried relentlessly for Ernst, and drank nothing but wine. When soldiers began accusing her of being a spy, Catherine Yarrow, Carrington’s friend, rescued her from this situation. They managed to reach Spain, but Carrington’s mental stability continued to crack.

Once in Madrid, Carrington stayed with friends until her delusions and paralyzing anxiety led to a psychotic break at the British Embassy. Carrington broke down, calling for the metaphysical liberation of humankind and threatening to murder Hitler. Following this outbreak, Carrington landed in a Santander mental asylum. While in the asylum in 1940, Carrington painted Down Below.

After undergoing convulsive therapy and treatment with powerful anxiolytics and barbiturates, the asylum released Carrington. Her keeper informed her that her parents wanted to send her to a South African sanitorium, but Carrington escaped to Portugal. It was here that Carrington found Renato Leduc, Mexican ambassador and poet.

Leduc agreed to marry Carrington so she could receive the immunity of a diplomat’s wife. The two spent the following year in New York, where Carrington recounted her experiences in her first memoir written in 1943 and called Down Below. Carrington also recorded her experiences in many paintings, including Portrait of Dr. Morales.

Leonora Carrington in Mexico

After spending a year in New York with Leduc, the two moved to Mexico. Although the pair divorced in 1943, Carrington remained in Mexico on and off for most of her life. While in Mexico, Carrington befriended Remedios Varo, a fellow European emigre, and Emerico Weisz, a Hungarian photographer who she married.

Weisz and Carrington had two sons, and archetypally feminine motifs permeate her work from this time. Carrington recognized the traces of an ancient magic force that lay in the acts of nurturing a family, growing food, and creating art.

She felt an overlap between her homely activities and the work of alchemists. The manipulation of inanimate matter to release life-giving properties lay at the heart of both. Carrington began to revisit the tempera paint medium during this time. Tempera was a common practice from the Renaissance period which involves mixing the pigment with egg yolk to produce a paint consistency that is tricky to master. Carrington felt that this paint medium imbued her art with the physical substance of life.

Careful study of the religious beliefs of Buddhism, local Mexican folklore, and the exploration of thinkers like Carl Jung greatly influenced Carrington’s artistic development. Carrington met Remedios Varo in Mexico, and the two began to study the kabbalah, alchemy, and the mystical writings of post-classic Mayans.

Although she lived in Mexico, Carrington continued to exhibit her work internationally. In England, the Surrealist patron and poet Edward James championed Carrington’s work, buying many of her paintings and arranging a 1947 exhibition at the New York Pierre Matisse Gallery. This exhibition was a significant one, as Carrington was the first female artist to have a solo exhibition at this prestigious gallery. So strong was James’ patronage that some of Carrington’s paintings still hang on the walls of his former family home in West Sussex.

Leonora Carrington and Women’s Liberation

After reading The White Goddess, published by Robert Graves in 1948, Carrington had a revelation. In this book, Carrington discovered the universal practice of worshipping the Earth Goddess in many prehistoric cultures.

The book covered mythology from ancient cultures throughout the Middle East, Western Europe, and England. Men brutally wiped out matriarchal societies and replaced them with patriarchal structures. Carrington began to incorporate these mythological figures, themes, and myths into her art, creating enigmatic and rich layers of meaning and feminist symbolism.

Carrington began to carve out her own niche style that differs immensely from the Surrealists who followed Freud’s teachings. Filled with alchemy and magical realism, Carrington’s paintings centered around symbolism and autobiographical details.

Carrington also portrayed female sexuality throughout her paintings. Carrington did not cater her expression of female sexuality to the conventions of the male gaze. Instead, she presented her own experiences of female sexuality. Many of Carrington’s paintings from the 1940s focus on the role of women in the creative process.

In Mexico, Carrington’s art was well-received. In 1963, the Mexican government commissioned a mural by Carrington for the National Museum of Anthropology. This mural is called El Mundo Magica de los Mayas. Carrington’s political activism continued throughout the 1960s and 1970s. In 1972, she co-founded the Mexican women’s liberation movement, and she held many student meetings at her residence.

As a result of her activism, Carrington was honored at the United Nations Women’s Caucus for Art where she received the Lifetime Achievement Award in 1986. Carrington was also awarded the National Prize for Sciences and Arts in Mexico in 2005.

The Late Life and Legacy of Leonora Carrington

Carrington began to divide her time between her Mexican home and visits to Chicago and New York from the 1990s. In addition to her paintings and prints, Carrington began to throw herself into bronze sculptures during these later years, crafting human and animal figures. Occasionally Carrington gave interviews about her life, but in 2011 she died at the age of 94 from complications with pneumonia.

Although she did not self-identify with the Surrealist movement, Leonora Carrington played a significant role in spreading Surrealism throughout the globe. In her writings and personal letters, Carrington was a communicator of Surrealist theory. Although, as it is with many successful women, her relationship with Ernst overshadows her notable artistic production, but she is slowly receiving more attention.

A 2013 retrospective exhibit was created in Carrington’s honor at the Irish Museum of Modern Art. The exhibition was called “The Celtic Surrealist,” and it celebrated the profoundly personal symbolism and visionary artistic approach of Carrington’s work. Carrington remains a feminist icon among artists. Her intertwining of magic, folklore, and autobiographical details has laid the path for other female artists like Kiki Smith and Louise Bourgeois to explore new ways to approach female physicality and identity.

Leonora Carrington Paintings

For Leonora Carrington, art was a line of communication between her inner world, the world outside, and the myths of her ancestors. Leonora Carrington’s paintings are steeped in symbolism, mythology, and feminine iconography. When she painted, Carrington would build up layers of her rich imagery with meticulous and small brushstrokes. We are going to look at several of Leonora Carrington’s paintings, from her earliest to some of her more recent.

Self Portrait (Inn of the Dawn Horse) (1937-1938)

As a self-portrait, this is one of the most accurate summaries of Carrington’s perception of reality. The painting explores her own femininity and her rejection of convention. Carrington has painted herself, dressed in androgynous riding clothes, facing the viewer in a blue armchair.

The female figure’s hand is extended outwardly towards a female hyena, who imitates both her gesture and posture. Carrington’s wild mane of hair reflects the colored coat of the hyena. Throughout her art and writing, Carrington often painted the female hyena as a symbolic representation of herself. The ambiguous sexual characteristics, power, and rebellious spirit of the hyena drew Carrington to it.

In the background of the painting, a white horse gallops easily in a forest through the window. A white rocking horse mirrors the position of this horse as it floats behind the artist’s head. Carrington came from a rigid upbringing which she fought throughout her life.

The contrasts between liberation and restriction and the transformations within this painting seem to capture her inner world around the time that she broke away from her family. We can already see Carrington’s characteristic use of autobiographical symbolism in this early painting, as the artist attempts to reimagine her reality.

The Meal of Lord Candlestick (1938)

This painting is another example of Carrington infusing her art with very personal symbolism. Carrington completed this painting shortly after she escaped her life in England to begin her affair with Max Ernst. Through the symbolism in this Leonora Carrington painting, we can see her rejection of her strict Roman Catholic upbringing.

Carrington used the nickname “Lord Candlestick” to refer to her strict and unemotional father. In the title of the painting, Carrington emphasizes her dismissal of the oversights of her father. The scene is Eucharistic, but Carrington transforms the religious symbolism into a display of barbarity. A voracious female form gorges on a male infant who lies on the table. Many historians believe that this table represents one in the grand banquet halls in the estate where she grew up.

Carrington makes a statement of her own insurgent journey towards personal freedom in France as she intentionally overturns the symbolic order of religion and maternity in “The Meal of Lord Candlestick”.

Portrait of Max Ernst (1939)

One of the earliest Leonora Carrington paintings, this portrait of Max Ernst was a tribute to their relationship. In the foreground of the portrait, Ernst stands tall, wrapped in a mysterious red coat and striped yellow stockings. Ernst is pictured holding an oblong and opaque lantern holding the reflection of a white horse.

Carrington often used the symbol of a white horse as her animal surrogate, as with the female hyena. In the left upper corner of the painting, there is another white horse, poised and frozen. The horse appears to be observing Ernst, and the two stand together, alone in a desolate frozen landscape. The scene seems to be symbolic of the time the two spent together while living in occupied France.

The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg) (1947)

We can see some of Carrington’s most prominent themes within this painting, including the matter of metamorphosis, transformation, and the concept of the divine feminine. You only need to glance at this painting to feel the immense power of the life-giving feminine. A majestic female form fills the composition, shrouded in a pale green cape and a red dress. The giantess towers over the trees below, emphasizing her stature. Carefully painted shapes and animals adorn the giantess’ gown, and two small geese seem to be emerging from below her cloak.

In her hands, the giantess is holding an egg, a universal symbol representing new life. On the landscape, tiny animals hunt, small figures forage, and geese fly clockwise around her. Carrington’s fascination with gothic and medieval imagery is visible in the scale, palette, and facture of this painting.

The flatly painted face of the giantess, illuminated by a golden circle, bears resemblance to a Byzantine figure. Many believe that the geese may harken back to Carrington’s Irish ancestry, in which the goose is a symbol of travel, migration, and coming home.

The composition of the piece resembles the techniques of Hieronymous Bosch. By including a host of strange, otherworldly figures who appear to be floating behind the giantess, Carrington hints at a marine environment. The colors are also reminiscent of the ocean, further suggesting that the images and ships are at sea. The composition in this painting melds the sky and sea together, communicating Carrington’s belief that art can blend worlds.

Ulu’s Pants (1952)

As with all of her paintings, Carrington infuses this piece with intimate autobiographical detail. The bizarre characters who inhabit the labyrinth world in this painting are reminiscent of the Celtic mythology of Carrington’s Anglo-Irish upbringing. Not only this, but Carrington intertwines various South American cultural traditions from her time living in Mexico.

It is also possible to see Carrington’s growing feminist angle, as this painting once again contains an egg as a symbol of feminine fertility. A strange red-headed figure in the lower right corner protects the egg. The concepts of fertility and life-giving alchemy are also present in the medium of this painting. Many of Carrington’s paintings from this period use tempera paint because it is made with egg yolk.

In the foreground, we can see a row of slightly unnerving figures standing in a straight line as if they were about to perform. These figures are joined by shape-shifting forms, believed to represent Carrington’s concerns with self-discovery and continuous rebirth. The strange creatures searching for a path through the maze in the back of the painting also communicate this notion of self-discovery.

Bird Bath (1974)

This piece is one of Carrington’s later works, and we can see her gradually begin to incorporate older female figures into her visual pantheon. Once again, Carrington calls on autobiographical details to complete her compositions, this time in the form of her childhood home, Crookhey Hall. The house structure in the background appears to be a two-dimensional facade like the one you would find in a play, and it is decorated with a bird motif.

In the foreground of the composition, there is an elderly female figure dressed in black. Many historians believe that this figure is a representation of Carrington at an older age. The figure is spraying red paint onto a bird who appears surprised by the activity.

Carrington appears to be recalling the Christian passage of baptism, represented by the large water basin and the crisp white cloth. The cloth is held by an assistant who is also dressed in black and wearing a mask reminiscent of death doctors. Some historians have suggested that the red bird may be symbolic of the dove of the Holy Spirit.

The whole ceremony appears to be solemn and slightly eerie but with a touch of humor. Carrington is perhaps contemplating transformations in this painting, with the depiction of herself representing her journey from young artist to the old and wise crone.

Samhain Skin (1975)

Carrington often includes mysterious figures from cultural mythology in her paintings, and this piece is no exception. In this composition, Carrington makes reference to the Samhain festival celebrated at the end of summer, on the 31st October, by ancient Celtic people. This painting is unique in that Carrington painted the collection of human-animal hybrids and various backwardly handwritten allusions to historical Gaelic deities and tribes onto real animal skin.

Carrington’s grandmother is said to have claimed that her side of the family was descended from the Sidhe fairy people, and these beings are represented in the composition. Although it is a lot of fun for us to read into the symbolism that Carrington infuses into her paintings, she never intended for her intricately layered and complex images to be decoded by the viewer. Instead, Carrington simply asks us to ponder over the images and investigate our own gut reactions to her offerings.

Leonora Carrington Books

While Leonora Carrington is perhaps most famous for her paintings, drawings, and sculptures, she was also a prolific writer. Carrington is credited with recording a great deal of Surrealist theory in her articles, letters, and books.

For Leonora Carrington, art and writing were ways for her to dive deeper into her internal psyche and turn the often tormenting thoughts into beautiful creations. Just like her paintings, Carrington’s writing is full of strange mythological creatures, to the point that the appearance of an ordinary human being becomes slightly unnerving.

Down Below (1945)

Following her incarceration in sanitariums and her escape to Portugal, Andre Breton encouraged Carrington to record her ordeal in writing. Somewhat of a Leonora Carrington biography, this short memoir was originally written by Carrington a few years after her break with reality, but this original manuscript disappeared.

In 1943, Carrington dictated the memoir in French. The French version was translated and published in 1944/1945. For Carrington, putting these excruciating experiences into writing was a way for her to cleanse herself of them. By processing them and sharing them with others, Carrington could lighten the burden and move forward.

Although the novel tackles some terribly dark moments in Carrington’s experience, her writing does not ask for pity, nor does she appear to pity herself. Her writing style is surprisingly detached as she recounts in incredible detail the fractured experiences of her broken mind.

One of the most prominent themes within this memoir is Carrington’s refusal to give in to her mental illness. Even when she experiences her darkest moments, she continues to fight to survive and move forward. We can highly recommend this book to everyone, whether you are yourself struggling with mental illness or not. It is a moving, deep dive into a deeply disturbed psyche and a story of resilience and struggle that can inspire others to find that strength within themselves.

- A stunning work of memoir by an unforgettable and brilliant artist

- A biography of one of the world's greatest surrealistt painters

- Carrington describes her life impersonally and without self-pity

The Hearing Trumpet (1976)

Sometimes called the occult twin of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland, this novel considers the aging female body. The narrative observes the story of older women committed to tearing down the institutional structures of patriarchy. In their place, these women desire to create a society of maternal sisterhood, and this novel is one of the first in the 20th century to consider gender identity as a concept.

Carrington’s views place motherhood and the creation and nurturing of life at the center of the experience of femininity. This opinion on the surface may differ from many other mainstream feminist attitudes, but Carrington is not diminishing the female human to her role as a mother. Instead, Carrington is celebrating, and encouraging us to celebrate, the magical and mystical ability of women as the creators of life.

- A book that falls perfectly within her anarchic and allusive oeuvre

- An old woman enters a fantastical world in this surrealist classic

- Our heroine is a woman who is "hard of hearing" but "full of life"

With her pantheon of mythological creatures and her deeply personal autobiographical themes, Leonora Carrington is a prized Surrealist artist. Although she rejected her association with Surrealism, as she rejected any other attempt to pigeon-hole her, she is a feminist and artistic icon. Although her life was full of torment and struggle, her fight and her creative resilience live on.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Leonora Carrington – The Pioneer of Feminist Surrealism.” Art in Context. March 25, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/leonora-carrington/

Meyer, I. (2021, 25 March). Leonora Carrington – The Pioneer of Feminist Surrealism. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/leonora-carrington/

Meyer, Isabella. “Leonora Carrington – The Pioneer of Feminist Surrealism.” Art in Context, March 25, 2021. https://artincontext.org/leonora-carrington/.