Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – Chronicler of Parisian Nightlife

French painter, printmaker, draftsman, and illustrator Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa was one of the most influential artists of the 19th-century Avant-Garde. During the post-Impressionist and Art Nouveau eras, Toulouse-Lautrec was a pioneer of the modern poster with his bold, colorful, and simplified style.

The Prince of Prints: Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec

| Date of Birth | 24 November 1864 |

| Date of Death | 9 September 1901 |

| Place of Birth | Albie, France |

| Art Movements | Japonism, post-Impressionism, Art Nouveau |

| Genre / Style | Drawing, printmaking, painting |

| Mediums Used | Oil on canvas, lithography |

| Dominant Themes | La Belle Epoch, Moulin Rouge, sex workers, advertisements, cabaret, celebrity |

In late-1800s Paris, Toulouse-Lautrec’s magnetic personality made him the preferred documenter of Paris after dark. The sex workers, performers, and other artists that surrounded him were the subjects of his popular posters and paintings.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s decadent lifestyle was plagued by disability, ridicule, alcoholism, and disease, which inspired his paintings but ultimately led to his demise.

Origins

Henri Marie Raymond de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa, better known as Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, was born in Albie, France on the 24th of November 1864. The elder of two children, Toulouse-Lautrec became the sole heir of an aristocratic family when his brother died at infancy. The family were descendants of the Counts of Toulouse, who had fought in the crusades almost a thousand years prior. By the 19th century, the Toulouse-Lautrec’s no longer had political power, but they retained substantial wealth.

His parents, Count Alphonse Charles de Toulouse-Lautrec-Monfa and Countess Adèle de Toulouse-Lautrec, were first cousins as they shared the same grandmother. Inbreeding was common with the French aristocracy of the time. A true blue-blooded eccentric, Henri’s father Count Alphonse was an avid hunter and philanderer who enjoyed dressing up in chainmail like his military ancestors. His religious mother doted on Toulouse-Lautrec and worried about his ill health.

Generations of inbreeding had taken their toll on the young Toulouse-Lautrec, who suffered a slew of hereditary health problems, including a rare genetic disease believed to be pycnodysostosis, which has come to be otherwise known as Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome. He also had a speech impediment.

At 13, his abnormally brittle bones were fractured on his left thigh bone, and at 14, the same happened to his right femur. The breaks never healed and as a result, Toulouse-Lautrec’s torso grew, but not his legs and his height never exceeded four feet eleven. For the rest of his life, he was in pain and would have to walk with a cane.

Once his ability to participate in physical activities was restricted, Toulouse-Lautrec directed his energy into painting and drawing.

Whenever he was bedridden, he threw himself into his art and soon showed promise, which led his father to appoint a family friend René Princeteau as an art tutor for his young son. Princeteau specialized in equestrian paintings, a subject that Toulouse-Lautrec tackled in The Spanish Walk (1899) and would return to over the years.

La Belle Epoch

In 1870, when Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was six years old, France waged war on Prussia and lost. Napoleon III, the nephew of the famous Napoleon Bonaparte, became a prisoner of war and the French empire came to an end. In 1871, the Prussians occupied France and established the first communist government in history, but were dethroned by the French after just 72 days.

Once the Prussians left France in 1875, democracy was established and a spirit of nationalism was promoted.

By the end of the 19th century, France was an extremely rich country reaping the rewards of slavery, colonialism, and the Industrial Revolution. Paris was transformed into a modern city of wide boulevards, and grand buildings.

The exuberance of the 1890s came to be known as La Belle Epoch, or “The Beautiful Age”. It is remembered as a time of peace, prosperity, optimism, indulgence, and unbridled hedonism.

There were new inventions, technologies, and social and political changes, all of which transformed the French existence. The entertainment industry was booming, and numerous cafes, cabarets, and theaters were opening. Artists, philosophers, writers, and performers converged in Paris to exchange ideas and make their mark.

A Young Artist

At the age of 17, Toulouse-Lautrec had left home and moved to Paris. In 1882, he enrolled to study with conservative academic painter Léon Bonnat. Under the direction of Bonnat, his formal training involved copying the works of old masters, figure drawing, and painting of models in classical poses. Toulouse-Lautrec then went on to study under the famous history painter Ferdinand Common for another five years. His infirmed perspective complemented the conventions of academic training, and he incorporated the influence of his initial training with Princeteau.

His inability to engage in physical activities like horseback riding inspired Toulouse-Lautrec’s preoccupation with participating as a keen observer. His paintings “A Woman and A Man on Horseback” (1879-1881) and “The Jockeys” (1882) show the early combinations of his various forms of tutelage.

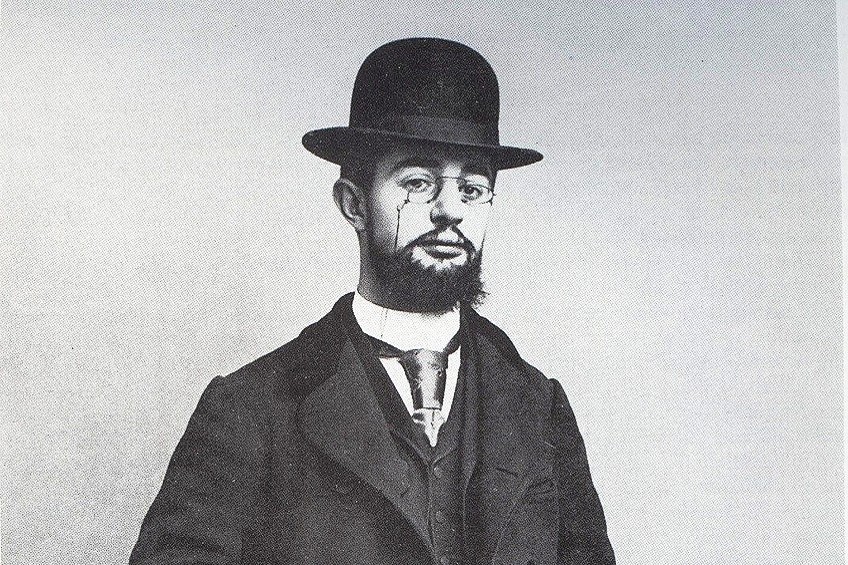

This is when the artist began thinking creatively about his physical attributes, enhancing or concealing them to hone his artistic style and persona. He painted his Self-Portrait (1885) with organic lines, which gave the impression of a quick self-study. Lautrec portrayed himself in a derby hat and glasses, which became his signature style. He was wearing a coat that covered his legs, revealing insecurity about their deformity. The loose brushwork, expressive shapes, and negative space make this a post-Impressionist work.

Post-Impressionism

Toulouse-Lautrec was exposed to Impressionist art as a student and was intrigued by the unfinished canvases and use of color. He began experimenting with the idea of depicting modern subject matter through vibrant pallets and light brush strokes.

But, unlike the Impressionists who focused on the changing light of the outdoors, Toulouse-Lautrec declared: “only the figure exists – the landscape should only be used to better understand the character of the figure.”

Post-Impressionism is a term for the art that came after Impressionism, which redefined nature as inclusive of inner vision and external sensation. Many Impressionists are also post-Impressionists. Lautrec found himself engaging with both Impressionism and post-Impressionism, reimagining works of artists he admired like Renoir’s Dance at the Moulin de la Galette (1876), which he had seen at the third Impressionist exhibition of 1877.

After being sketched en Plein air, Toulouse-Lautrec’s unsettling studio version of “Moulin de la Galette” (1889) was executed in loose oils. He juxtaposed the loudness of the background with a cold, spacey foreground of figures in synthetic colors.

While studying at the atelier de Common, Toulouse-Lautrec became close friends with artists like Vincent van Gogh. Toulouse-Lautrec was significantly influenced by the painter Edgar Degas’ use of modern subject matter, strong lines, and bold color. Degas enjoyed the ballet but was drawn to its dark side. Ballerinas of the time were referred to as “petite rats” as they were poor, dancing out of desperation, often leveraging sex for money. At last, Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings found their niche.

Artworks by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec

In an exuberant era like La Belle Epoch, when so much was in flux, Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec’s art and posters were not only a record of their time but a force of change within the parameters of what art could do.

Paintings

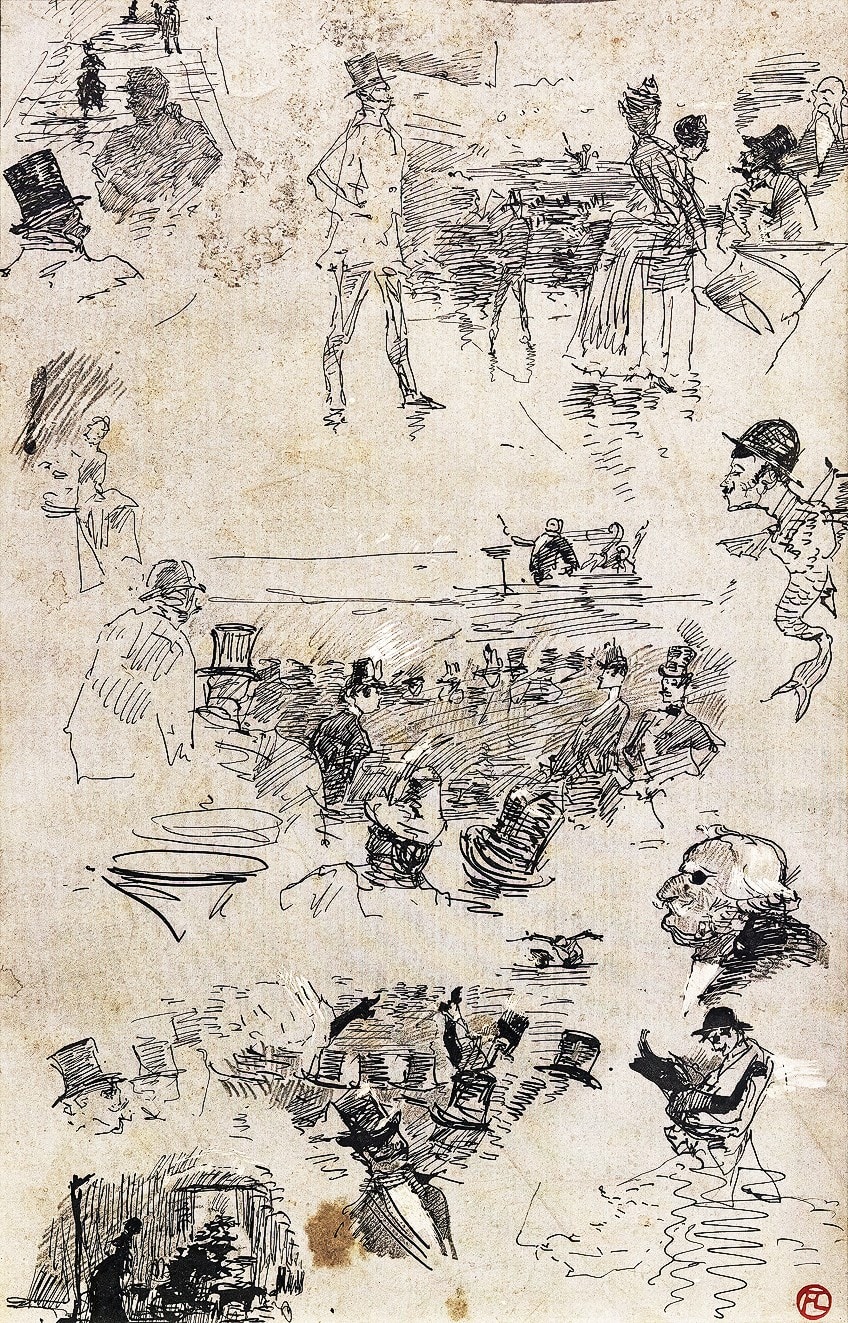

Though he had experimented with the strong palette and expressive brushwork of the Impressionists and Post-impressionists, Toulouse-Lautrec never aligned himself with one sole style. His paintings have a sense of immediacy despite being carefully planned. Toulouse-Lautrec carried a small sketchbook wherever he went.

The thousands of rapid jottings that survive show us how frequently he drew and how his major images were developed from quick visual studies.

Because of his interest in the figure, Toulouse-Lautrec asked his friends to pose for his paintings. By 1891, ten of Toulouse-Lautrec’s paintings, including three portraits, were presented at the seventh exhibition of the Société des Artistes des Independence.

The portraits featured his friends, all three young men of extremely good fortune. But many of Toulouse-Lautrec’s favorite models were lower-class working women.

He was interested in painting the unseen side of various characters and it was obvious that Lautrec had respect and love for his subjects. He depicted them without judgment and with a great deal of empathy, perhaps owing to his sense of being an outsider because of his physical limitations.

Montmartre

Once Toulouse-Lautrec discovered the district around Bonnat’s studio where laborers and luminaries comingled, it changed his practice. Because it was a cheap place to live and work, Montmartre had become popular with artists. The steep cobbled streets, which were full of charm and character, became home to Lautrec, who rented an apartment and studio in the district and immersed himself in the bohemian lifestyle.

Montmartre was an exciting place at the end of the 19th century.

Parisian society was embracing a new liberal attitude and Toulouse-Lautrec and his fellow artists were inspired by the vibrancy of Montmartre’s life. The local hangouts buzzed with talk of freedom, radicalism, anarchy, and sexual exploration, which was an awakening for Lautrec.

Unlike the Impressionists, who were known for depicting scenes of upper-middle-class life, Toulouse-Lautrec fell in love with the atmosphere and artificial lighting of the new urban nightlife.

At night, he could be found drinking lots of alcohol, socializing, and making sketches, which he would transform into paintings by day. His pictures showed Montmartre as a tabernacle of human activity. By 25, he was a well-known figure and a regular at many cabarets, dance halls, circuses, nightclubs, cafes, bars, and brothels.

At the Moulin Rouge (1892 – 1895)

The Moulin Rouge in Paris was built by Josef Olerr in 1889. With its signature red windmill façade, the cabaret and decadent dance hall quickly became the most famous of them all, particularly for the invention of the cancan, a seductive dance done by its courtesans. The debauchery associated with the era is largely thanks to this nightlife epicenter that eventually became home to Lautrec and his friends.

Lautrec befriended the famous entertainers at the venue and these characters populated his work. He had already established a reputation as a daring illustrator of provocative characters, but the Moulin Rouge would contribute to this legacy.

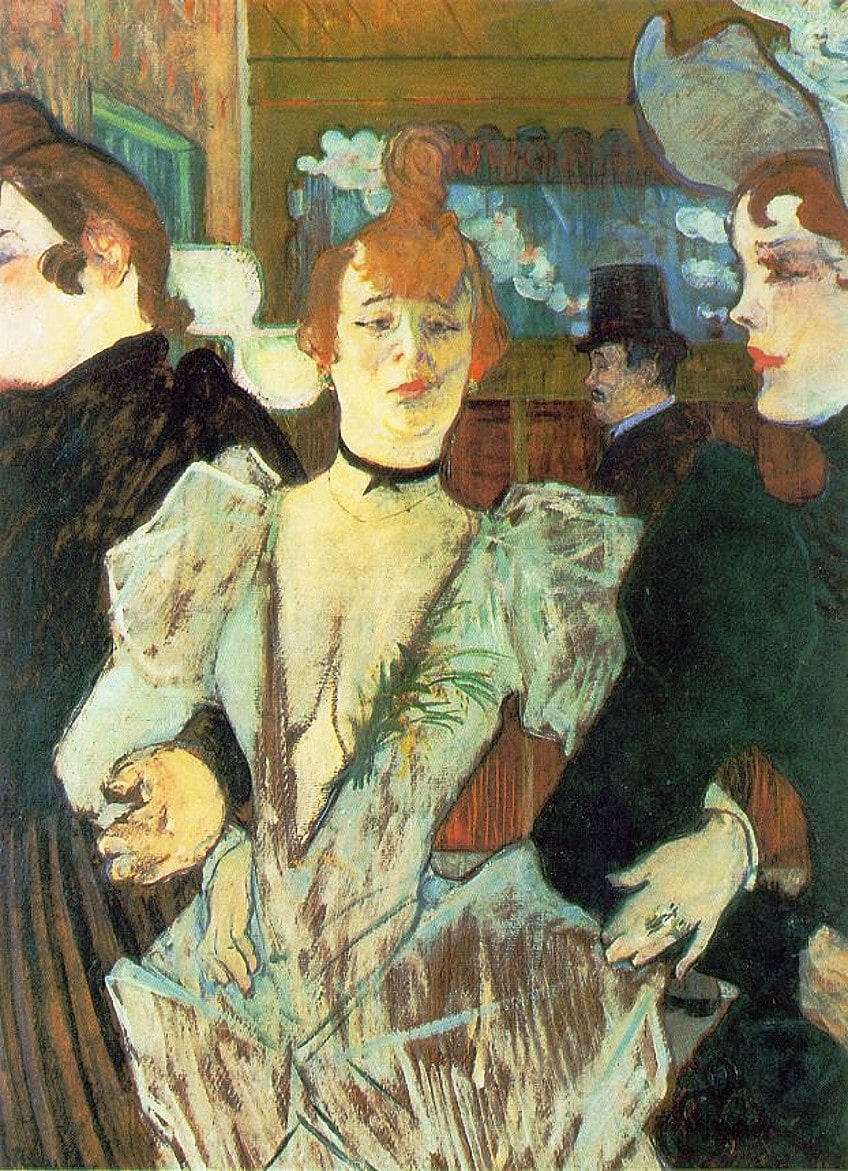

At the Moulin Rouge (1892) is an oil painting on canvas that is both a portrait and a genre scene. It depicts Paris’s nightlife and gives us a view inside the Moulin Rouge. It features a group of Lautrec’s friends gathered in a circle at the center of the painting. La Goulue is at the back with Jane Avril and her trademark red hair. The female figure on the right in the foreground with the garish, elongated face is a singer. Her oddity radiates and draws the eye to the right of the composition.

This is one of the most well-known Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec paintings.

It evokes modern-day paparazzi photographs but offers something more intimate. It is a self-portrait; Toulouse-Lautrec paints himself into the center background where he is dwarfed by a tall man standing next to him. He seems to be claiming his position as the official court artist to these celebrity figures.

Sex Workers

Influenced by Degas and Gaugin, Toulouse-Lautrec painted the bohemian Paris of great sexual adventure. Unlike Degas though, Lautrec was accepted into the private lives of prostitutes and pimps. In the early 1890s, Toulouse-Lautrec was commissioned to produce a portrait series of courtesans at a brothel. He lived there while he worked and became very familiar with the women, who kept him company. He could relate to them because they were accustomed to being marginalized, and mutual trust was formed.

Hidden away from the revelry of the Moulin Rouge, Toulouse-Lautrec produced sensationally sentimental studies of intimacy in women’s spaces.

One such portrait of a sex worker, Golden Helmet, so-called because of the way she wore her hair, is The Streetwalker (ca.1890-1891), which defiantly depicts this creature of the night in the bright light of day. She appears at ease, memorialized through Lautrec’s enormous sensitivity.

Toulouse-Lautrec offers his humane, realistic depiction of the women who lived and worked in Montmartre in roles that society had traditionally frowned upon.

His subjects are neither idealized nor derelict. Lautrec captured the naturalness of these women’s lives, preventing in many instances the total erasure of their authentic existences. Because of this, Lautrec’s gaze is politically profound.

Posters

The development of mass media in the 19th century revolutionized the advertising industry. In 1881, French advertising laws were changed to permit printed advertisements into public spaces. Parisian establishments, which drew huge crowds from the freshly emergent pleasure-seeking middle class, now needed eye-catching promotional imagery.

Technological advances in lithography were being pioneered by Parisian artists in the 1890s.

Lithography was an ideal advertising medium and Toulouse-Lautrec thrived on its collaborative aspect. He worked with and learned from professional printers. Toulouse-Lautrec art maximized the technical innovations of the medium.

La Goulue

In 1891, the owners of the Moulin Rouge approached Toulouse-Lautrec, who was a regular at the club, with a prestigious commission to create a show-stopping promotional poster. The lithographic poster Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891) turned the advertising poster from simple painted text into an art form.

The color lithograph on paper was the first serious publicity poster by Toulouse-Lautrec.

The chic composition of the image features simple bold, black outlines and solid areas of bright color. The reduced design was modern, striking, and exotic, inspired by Japanese woodcut prints, which were fashionable in Paris at the time. The repetitive lettering and impressive scale of the poster made it inescapable. The poster was almost two meters high, consisting of three separate sheets of paper. It was not easily produced and dwarfed other posters on the streets of Paris at the time.

The dark silhouette of the crowd in the background boldly reveals French Belle Epoch fashions. Toulouse-Lautrec was known to exploit the marketing power of his celebrity subjects, so, in the absolute center of the image is La Goulue, or “The Glutton”, whose real name was Louise Webber, a favorite subject of Lautrec’s and notorious Moulin Rouge dancer. In the foreground, Lautrec placed her top hat-wearing dance partner Valentine Le Desaus.

The image oozes sexuality. La Goulue is pictured in a red polka dot dress throwing one leg in the air. It was said that she wore no underwear during her performances, and we are being directed to look up her skirt. Her erotic cancan number involved knocking the top hats off customers’ heads in the bar around her and attracting spectators in numbers. The characters are caricatured through their exaggerated faces, body features, and poses.

Overnight, “Moulin Rouge: La Goulue” catapulted Toulouse-Lautrec into the public spotlight and made him one of the most sought-after designers.

Some 3000 copies of La Goulue were plastered all over Paris in late December 1891. The posters were so popular that collectors began peeling them off the walls as soon as they were mounted. It was the first of over two dozen iconic Toulouse-Lautrec posters, which he produced over the next decade, promoting various venues and performers.

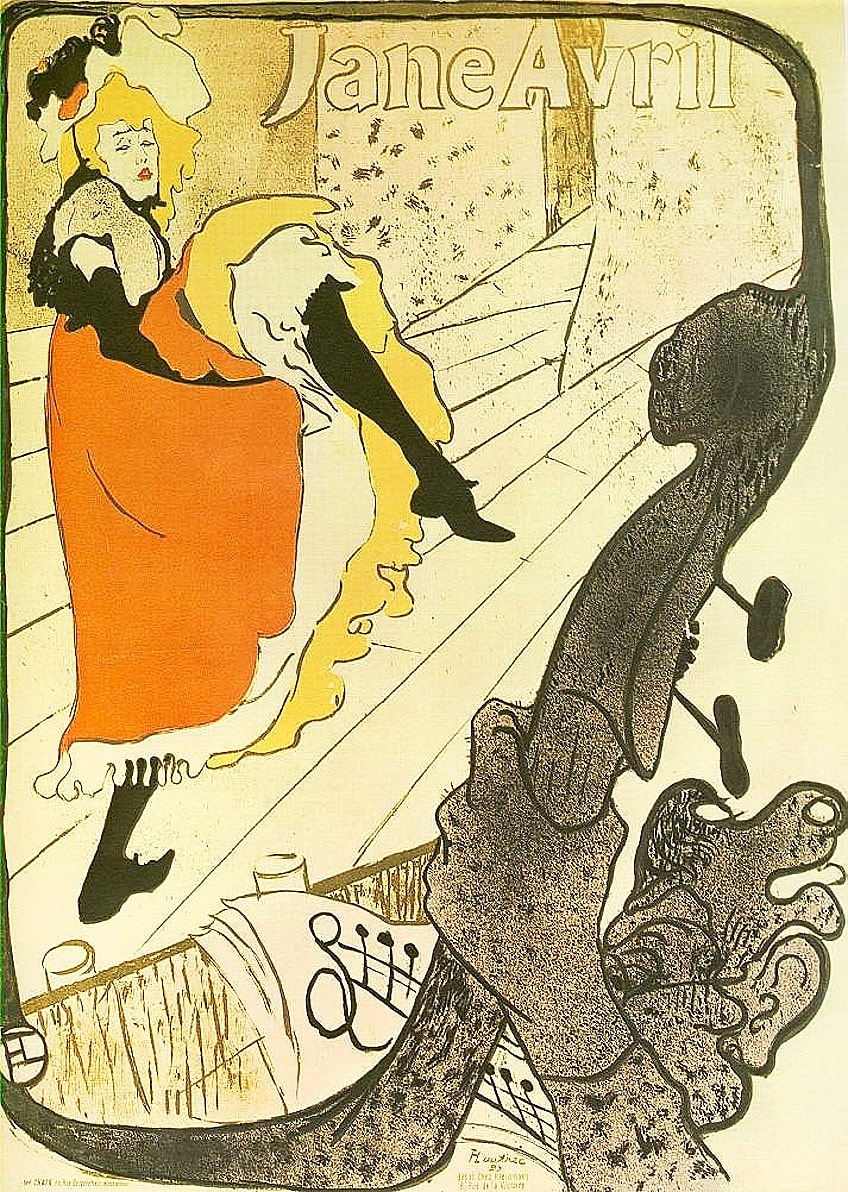

Jane Avril

Jane Avril was another famous dancer at the Moulin Rouge. Toulouse-Lautrec and Avril likely met at the Moulin Rouge, but their relationship went far beyond the performance venue. They became life-long friends and Avril served as Lautrec’s model for a long time.

The most touching thing about their relationship is the generously varied ways in which Toulouse-Lautrec depicted this extraordinary dancer. Lautrec shows Avril in all manner of different guises. He did portray her dancing or on stage, but he also showed her as a quiet, private individual in tender moments away from the bright lights.

Her flamboyant performances, which thrilled audiences, were fueled by her history with mental health and sex work. They might have been an odd pair, but the two had a lot in common; being both famous figures in the bohemian elite of Montmartre and both having rather strange physical features. Toulouse-Lautrec, of course, was quite short, while Avril had her famous nervous twitch, which was part of her stage persona.

The caricatured color lithograph on paper, Jane Avril (1893), shows her doing her signature move on a lively stage. Mademoiselle Eglantine’s Troupe (1896) and Jane Avril (1899) are also color lithographs. These seem to be creating a fantastic brand for the dancer with her serpent-wrapped slender body, and shocking red hair, which signified prostitution at the time. But in Divan Japonais (1893), Toulouse-Lautrec cast Avril in the role of an audience member. She plays an aristocratic woman observing another performer on her stage.

The Art of Design

Toulouse-Lautrec art featured signature sinuous, stylized lines, fields of flat color, and surface patterns were inspired by Ukiyo-e woodblock prints. In the latter half of the 19th century, prints by Ukiyo-e artists such as Katsushika Hokusai and Utagawa Kuniyoshi flooded the European market.

These prints stimulated the trends of flat color, elongated women, and bold lines. Parisian artists called their craze “Japonisme”.

Artists who incorporated Japonisme into their work included Impressionists such as Claude Monet, Auguste Renoir, Marie Cassatt, and Camille Pissarro. Post-Impressionists like Vincent van Gogh also took their cues from Ukiyo-e woodblock prints and, over time, this appropriation would result in the Art Nouveau illustrator posters of Thèophile-Alexandre Steinlen and Alphonse Mucha.

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec’s influence from Japanese woodblock prints appears in his bold lines, bright colors, and simplistic forms, as well as his representations of women, flat figures, perspective, and space.

He created 30 lithographic posters, which dissolved the traditional bounds between high art and graphic design. His posters brought critical attention to the field of advertising. By combining popular culture with commerce and art history, Toulouse-Lautrec paved the way for artists like Andy Warhol.

The End of an Era

The excess of La Belle Epoch came with a price. Toulouse-Lautrec enjoyed VIP status in Parisian haunts such as the Moulin Rouge, where he became known as a drunk. He was often in a tremendous amount of pain, which he numbed by drinking himself into a stupor. Legend has it that he even hollowed out his cane and filled it with alcohol.

Eventually, Toulouse-Lautrec’s hedonistic lifestyle took its toll.

His wealthy family did not approve, nor did they understand his bohemian lifestyle choice. His mother, who had always been concerned with his physical wellbeing, eventually gave up. His father was so outraged by his decisions that he disinherited Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and his uncle supposedly burned his paintings.

Even his colleagues looked down on his way of life and ridiculed him for associating with unsavory types. Degas once remarked that Toulouse-Lautrec’s brothel paintings “stank of syphilis”. Toulouse-Lautrec had indeed contracted syphilis sometime in his 20s, which wreaked havoc on his already fragile mental and physical states, suffering from delusions and hallucinations.

In February 1899, he was committed to a mental asylum, where he remained for several months. In May that year, Toulouse-Lautrec was released and he returned to work, but it was not to last. His later work was increasingly moody and downbeat, and he bounced back into depravity.

In the summer of 1901, Henri de Toulouse Lautrec suffered a stroke that left him partially paralyzed. He later died on the 9th of September, aged only 36.

Recommended Reading

We have scoured Amazon for its best recommendations to compile a couple of books for those who would love to learn more about the artist Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec or have a closer look at these images.

Toulouse-Lautrec: A Life (1994) by Julia Frey

This biography is based on thousands of letters between Toulouse-Lautrec and his loved ones. As such it gives detailed insights into the artist’s personal life including what happened with his disabilities and the true nature of his relationship with his parents. Consequently, this book paints a detailed picture of the artist Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

- A definitive chronicle of the life of one of the world's great artists

- Thousands of previously unavailable family letters

- Captures the essence of Toulouse-Lautrec's life

The Paris of Toulouse-Lautrec: Prints and Posters From The Museum of Modern Art (2014) by Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec and Sarah Suzuki

This book takes a thematic and in-depth approach to survey the artist’s contribution to the graphic arts. It operates as an exhibition catalog and looks through the collection of Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec prints, posters, and other printed media found at the Museum of Art in New York featuring a text by its associate curator in the Department of Drawings and Prints Sarah Suzuki.

- Prints and posters contextualized in the milieu they arose

- Thematically organized groupings of Toulouse-Lautrec’s prints

- Each print is accompanied by an illuminating essay on the theme

The spirit of Toulouse-Lautrec survives in the prolific output he left behind. The hundreds and thousands of posters, prints, paintings, and drawings made over the course of his career have preserved Toulouse-Lautrec’s legacy. His touch is still visible on the streets of Montmartre; it resounds in the work of his successors such as Pablo Picasso who shared his love for Parisian nightlife, and in Hollywood visualizations of the heyday of the Moulin Rouge, which tragically burned down in 1915.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome?

Toulouse-Lautrec Syndrome, otherwise known as Pycnodysostosis, is a rare genetic disease, which has come to be associated with Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec because he is believed to have had it. It stunted his growth, causing brittle bones, facial abnormalities, and deformations of the hands and other parts of the body.

Was Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec an Art Nouveau Illustrator?

Yes, in what was seen as a gloriously modern era, Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec’s art borrowed from the bold figures, fresh perspective, and flat color fields of Japanese artists. This trend in modern pictorial devices by French artists came to be known as Art Nouveau.

Why Was Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec Famous?

Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec was one of the pre-eminent artists who combined commercial and high art. His iconic posters of entertainers and empathetic portraits of sex workers captured the glamour and scandal of late 19th century Bohemia in Paris.

Heidi Sincuba was the Head of Painting at Rhodes University from 2017 to 2020 and part of the first Artist Run Practice and Theory course at Konstfack in Stockholm, 2021. They completed their BFA at Artez Arnhem in the Netherlands, MFA at Goldsmiths University of London, and are currently a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Cape Town.

Heidi Sincuba’s own practice explores fugitivity through painting, drawing, text, textiles, performance, and installation. This praxis is founded on a conceptual intersection of biomythographic experimentation, existential automatism, and African ancestral knowledge systems. These methodologies of multiplicity result in a fluid and speculative aesthetic, continually manifesting and metamorphosing its material conditions.

Learn more about the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Thembeka Heidi, Sincuba, “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – Chronicler of Parisian Nightlife.” Art in Context. March 25, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/henri-de-toulouse-lautrec/

Sincuba, T. (2022, 25 March). Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – Chronicler of Parisian Nightlife. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/henri-de-toulouse-lautrec/

Sincuba, Thembeka Heidi. “Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec – Chronicler of Parisian Nightlife.” Art in Context, March 25, 2022. https://artincontext.org/henri-de-toulouse-lautrec/.