Kara Walker – Interesting Facts About Artist Kara Walker

Kara Walker, one of America’s most accomplished and versatile artists today, initially wowed the world with her theatrical large-scale silhouette cut-outs and shadow puppetry. Her work is provocative, powerful, and some would argue, even obscene, but it is nonetheless aesthetically pleasing and surprisingly elegant. Her work draws from historical narratives plagued by sexuality, violence, and subjugation, and exposes the lasting psychological effects of racial inequality. By exploring current racial and gender stereotypes, her work enables viewers to develop a greater awareness of the past. This article unpacks Kara Walker’s biography in more depth.

Table of Contents

Artist in Context: Who Is Kara Walker?

| Date of Birth | November 26, 1969 |

| Country of Birth | Stockton, California, U.S. |

| Art Movements | Contemporary Art |

| Mediums Used | Painting, shadow puppetry, film, drawing, sculpture, and cut-paper silhouettes. |

Kara Elizabeth Walker, a renowned and highly respected Black American artist, has produced some of the most important contemporary works of art in recent years. Walker is a capable and multidisciplinary artist whose practice includes many mediums, such as painting, printmaking, installation art, drawing, sculpture, and filmmaking.

Most notable, however, are her room-size black cut-paper silhouette compositions that examine race, gender, sexuality, violence, and identity.

When Walker was only 28 years old, she became one of the youngest MacArthur Fellows ever, receiving the award in 1997. Kara Walker’s biography continued to grow with rapid speed, and over the years, her work has been collected and exhibited in prestigious museums around the world.

Childhood

Kara Walker was born in 1969 to an academic family in California. As early as age three, young Kara Walker was inspired by her father, Larry Walker, who was both a painter and professor. When Kara Walker was 13 years old, the family moved to Stone Mountain, Georgia, following her father’s work. For Walker, this move was a horrible culture shock.

Moving from coastal California, which was culturally diverse and progressive, Stone Mountain was the opposite and shockingly still held Ku Klux Klan rallies.

In this new environment, young Kara Walker endured horrific racial stereotypes and she recalled that at her new high school she was often called a “nigger” and “monkey”. To escape from this new reality, Walker sought refuge in the library, where she gained deeper insight into the cultural norms and discriminatory past of the South.

This would largely inform her work to come later in her life.

Education

After graduating from high school, Walker enrolled in the Atlanta College of Art. Here, she developed a deeper aptitude for painting and printmaking. She felt uncomfortable exploring race politics in her work, even though her professors pressured her to do so, something she believed minority students were unfairly expected to do.

After graduating with her BFA, Walker attended RISD to pursue an MFA.

Walker was a phenomenal researcher, which allowed her to meticulously explore African American history in art and literature. This led to her incorporation of racial themes and sexual violence into her work. During her MFA, where she began her exploration in paper-cuttings and silhouetted theatre-like films, Walker found her voice and confidence that became the foundation for her successful and highly influential career.

Career

Walker’s first installation was a critical success and led to her being represented early on in her career by a major gallery, Wooster Gardens (now Sikkema Jenkins & Co.). The installation was titled Gone: A Historical Romance of a Civil War as It Occurred Between the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994). Walker was only 24 years old at the time. The exhibition, which quickly became a hot topic, featured a cut-paper silhouette mural portraying sex and slavery in the Antebellum South.

Several subsequent solo exhibitions cemented her success, and in 1998 she was the second youngest artist ever to receive the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation’s “Genius Grant”.

Since this initial success, Walker’s works have been widely collected and exhibited by galleries and museums around the world. In 2002, Walker represented the United States at the São Paulo Biennial. In the same year, she chose to move to New York as she was given a position on the faculty of the School of the Arts at Columbia University, where her students were not much younger than her.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art featured her exhibition After the Deluge in 2006, which was inspired in part by Hurricane Katrina. Following this was a major traveling exhibition organized in 2007 by the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, titled My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love.

2007 was a big year for Walker, as she was also named by Time Magazine as one of the “100 Most Influential People in the World”.

Another major solo exhibition was held at the Art Institute of Chicago, titled Rise Up Ye Mighty Race! (2013). Since then, Walker has had numerous solo exhibitions, including a recent retrospective in 2022 at the De Pont Museum of Contemporary Art in Tilburg, the Netherlands titled A Black Hole Is Everything a Star Longs to Be. Several public collections around the world house Walker’s works, including Tate, UCLA Museum of Contemporary Art, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Weisman Art Museum, Menil Collection, and Muscarelle Museum of Art.

Facts About Kara Walker

Despite her fame, many parts of Kara Walker’s life are shrouded in mystery. This section addresses a few of these mysteries while answering some of the many frequently asked questions about Kara Walker, like “When did Kara Walker start making art?” and “Why does Kara Walker use silhouettes?”. Below are some interesting facts about Kara Walker.

An Early Start

When did Kara Walker start making art? This question often features in interviews with the artist, partly because of how incredible the answer is. While we don’t know exactly when she started making art, we know when she knew she would be an artist.

Quoted in a 2006 article by Flo Wilson, Walker states that watching her father work on his drawings, she knew from as early as two and a half years old that she wanted to be an artist.

Kara Walker’s Personal Life

Walker maintained a low profile in her personal life, despite her stardom since her twenties. Her first marriage, and eventual divorce, was to Klaus Burgel, a German jewelry designer and Rhode Island School of Design professor, in 1996. The couple had a daughter, Octavia. Over the years, Walker managed a consistent career, whilst maintaining a healthy relationship with her daughter.

Kara Walker’s Silhouettes

Kara Walker’s silhouettes are among her most famous art mediums. Many people wonder why she uses silhouettes and what their significance is in her work. Walker started experimenting with silhouettes in graduate school, arguing that their simplicity and elegance eased the “frenzy” in her mind. Paper cut-outs and silhouettes can convey a great deal with little information.

Walker argues that this is exactly how stereotypes work, making the silhouette a powerful metaphor in her work.

Kara Walker’s Paintings

As a young artist, Kara Walker loved painting. Collections like the Museum of Modern Art still house many Kary Walker paintings and etchings. Despite this, Walker did not continue to use painting as her core creative medium for very long. During the 1990s, Walker stopped painting because she believed that the medium was deeply associated with white male patriarchy. Instead of painting, Walker experimented with paper silhouettes to escape conventions.

Controversy in Kara Walker’s Artworks

Despite Walker’s continued recognition and acclaim, her work was often criticized for its use of racial stereotypes. Betye Saar, an acclaimed political African-American artist, was one of Walker’s most vocal critics. Saar, who was involved in the Black Arts Movement in the 1970s, challenged negative stereotypes about African American culture in her work, and she expressed concern over Walker’s work, saying that Walker had “gone too far”.

Saar criticized Walker’s use of imagery, calling attention to its violent and sexually graphic nature, and asserting that African Americans are being betrayed by racist images masquerading as art.

While several critics argued that Kara Walker’s art perpetuates negative stereotypes, reversing representations of race in America, others applauded her courage to expose the absurdity of these stereotypes.

Seminal Kara Walker Artworks

Kara Walker’s art has evolved over decades from drawings, paintings, and etchings, into silhouettes, film, sculpture, and more. Her oeuvre is large and impressive and she has created countless influential and powerful works. Below we discuss only a select few works that cemented her as one of the most prominent practicing African American contemporary artists today.

Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart (1994)

| Artwork Title | Gone: An Historical Romance of a Civil War as it Occurred b’tween the Dusky Thighs of One Young Negress and Her Heart |

| Date | 1994 |

| Medium | Wall installation |

| Collection | The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

Introducing her signature style, this extensive wall installation marks the artist’s first venture into the art world. Numerous sources inspired the epic title of this work, including Margaret Mitchell’s book Gone with the Wind (1936) and a passage in a pivotal Ku Klux Klan text by Thomas Dixon, which describes the manipulation of a “tawny negress”. The silhouettes of figures dressed in 19th-century costumes lean toward each other under the moonlight, suggesting a storybook romance.

When examining the scene closely, however, graphic depictions of sex and violence become apparent.

In the 19th century, silhouettes were considered “women’s work”, and African American women might have had access to the art form. Walker chooses this medium to revisit historical and current ideas of race and violence. Silhouettes rely on visual clues based on a person’s general and stereotypical physical features to symbolically communicate to the audience. Walker uses this characteristic of silhouettes to tell stories and to examine the pseudoscientific practices that allegedly determined an individual’s intelligence and worth based on the shape of their face and head.

The work is full of fanciful details, like 19th-century hoop skirts worn by female characters in the scene.

The scene however becomes strange when other surrealist and obscene details appear, like a single figure being swept into the air by an enormous erection. This, Walker argues, references the violent “manhandling” of a group of people by another group. This, she argues, is still embedded within our consciousness today of how we perceive ourselves and those who are deemed “other”.

The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven (1995)

| Artwork Title | The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven |

| Date | 1995 |

| Medium | Wall installation |

| Collection | The Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth |

This Kara Walker artwork, like many other of her works, is presented on curved walls. This is inspired by the 19th-century cyclorama which offers a 360-degree view of a scene to make its viewing more immersive. This cyclical view also becomes a metaphor that Walker utilizes to suggest that the past, present, and future operates in cycles that continually grow from without and within each other. This alludes to the history of racial oppression that still manifests in the world today.

The tableau features life-sized figures create a scene of horrifying violence, including the torture and murder of slaves.

The work is a combination of fact and fiction, partly inspired, as the title suggests, by Uncle Tom’s Cabin, a famous novel written in 1952 by Harriet Beecher Stowe. The tableau features two female figures, possibly a mother and child, who are nursing each other. Three other children are depicted circling another figure who is wielding an axe.

More surrealistic features appear when a man without pants is shown connected via a cord to a fetus.

In this artwork, the entire scene is displayed on one plane and only in black and white, flattening the layers and making details obscure and ambiguous. There is a certain morphing of figures that makes it unclear where the one starts and the other ends, opening the narrative up to multiple readings and interpretations. This ambiguity is intentional as Walker believed that all stereotypes rely on such ambiguities.

Untitled (John Brown) (1996)

| Artwork Title | Untitled (John Brown) |

| Date | 1996 |

| Medium | Gouache on paper |

| Size (cm) | 165 x 130.8 |

| Collection | The Dakis Joannou Collection, Athens |

Many of Walker’s works created in the 1990s featured celebrated people and events of abolitionist history, and this work is one of them. Inspired by John Brown, the famous leader of the 1859 raid at Harpers Ferry, Virginia, this Kara Walker artwork is a large-scale gouache painting on paper made in 1996. During his lifetime, white people were shocked by Brown’s aggressive actions in the name of abolition.

Brown is seen by many as an abolitionist hero. After the 1859 raid, Brown was marked as a traitor and sentenced to death.

Walking towards his execution, witnesses were astonished when Brown stopped next to a black woman and kissed the child in her arms. The event has been depicted by many artists since his death. These depictions all seemed to beautify the event, situating him as a hero and martyr. Walker’s painting, however, re-imagines the occasion that so many artists represented. Awash in sepia tones, the painting features the three figures engaging with each other, Brown, the mother, and the slave child. In Walker’s depiction, the child pulls viciously at John Brown’s nipple with its teeth, stretching it out severely.

Brown is depicted as an old bearded man who turns away from the child, but he shows no aggression or frustration towards the child in any other way. Walker also re-envisions Brown as being naked, thus taking away all of the visual markers that suggest his patriarchal power. This version of Brown seems subservient to the child, as he turns away in pain as the mother impatiently thrusts the child forward, towards Brown. It is possible that the child biting at the man’s nipple could reference slave women who were expected to nurse the white children of their masters.

Brown seems to suggest that there is a kind of inefficiency and lack of sustenance in Brown’s martyrdom as slavery was not ended by his act.

The engagement between the three figures suggests that Brown might have had a sexual relationship with the woman, alluding to how enslaved women were expected to obey their master’s desires. Walker seems to ask the viewer through this critical work to re-examine those we see as heroes.

A Subtlety (2014)

| Artwork Title | A Subtlety |

| Date | 2014 |

| Medium | Installation with white sugar, molasses, polystyrene, and resin |

| Size | Installation featuring a 35-foot high and 75-foot long sugar sculpture |

| Location | Originally shown in Williamsburg, Brooklyn |

Walker’s work often has epic titles, and this artwork is no different. Referred by many simply as A Subtlety, this Kara Walker artwork has the full title of the Marvelous Sugar Baby, an Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant.

This work is a massive sculptural installation of a nude overly-sexualized sphinx-like figure made out of sugar.

The sphinx resembles a black woman and wears a “mammie’s kerchief”. The sugar sculpture was created at the Domino Sugar Refinery in Brooklyn and exhibited weeks before the building was to be demolished. This ambitious work was Walker’s first large-scale solo project, supported and commissioned by Creative Time, a public arts organization. Walker dedicated the work to the many unpaid and overworked, laborers who worked in sugar cane plantations as slaves over the world. Domino Sugar Refinery was once the largest in the world.

This site-specific work is rich in layered histories and meanings. With its large white shape, the sphinx is reminiscent of Walker’s silhouettes, and just like her silhouette works, the work draws on the continued racial, social, and economic inequalities of America and beyond. The whiteness of the sugar is also significant, as cane sugar is naturally brown, but it had been increasingly bleached by slaves as a greater demand in the West grew for confectionaries.

Next to the colossal white sphinx are sculptures of young black boys. These smaller sculptures were made of resin and molasses, and melted away in the heat by the end of the exhibition.

The heat in the sugar refinery that melted the sculptures alludes to the horrid conditions in which the slaves worked in that space. Boys often lost their limbs or even died, as it was so dangerous to feed sugar into the mills, something that had to be done manually. The disappearance of the sculptures of the boys is a powerful metaphor that honors the unseen people and undocumented events that accompanies slavery.

Book Recommendations

Kara Walker is one of the boldest contemporary African American artists living today, and her works are among the most powerful when addressing issues of racism, sexual violence, and identity politics. If you would like to know more about Kara Walker’s paintings, silhouettes, drawings, or other work, then the books below are a perfect start.

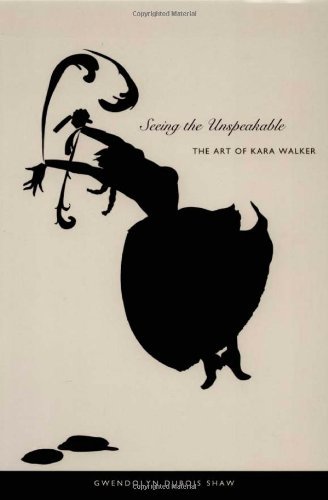

Seeing the Unspeakable: The Art of Kara Walker (2004) by Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw

Kara Walker’s controversial art is examined in depth in this book. The author analyses four of Walker’s pieces: The End of Uncle Tom and the Grand Allegorical Tableau of Eva in Heaven, John Brown, A Means to an End, and Cut. The book situates Walker’s life and career, and her work is contextualized concerning contemporary artists like Faith Ringgold, Carrie Mae Weems, and Michael Ray Charles.

- Provides a sustained consideration of the controversial art of Walker

- Analyzes the inspiration for and reception of four of Walker’s pieces

- Reveals a powerful artist who is questioning, rather than accepting

The author describes Walker’s de-sentimentalized images of slavery and racial stereotypes as deliberately challenging viewers’ perceptions. In this book, Walker is positioned as a powerful artist, who challenges, rather than accepts, the social responsibility strategies of her parent’s generation, whilst exposing America’s still conflicted racist present.

Consuming Stories: Kara Walker and the Imagining of American Race (2016) by Rebecca Peabody

The storytelling in Kara Walker’s art is rooted in 19th-century American history, which continues to have implications in the present. In this thought-provoking publication, Kara Walker’s visual storytelling is compared with literary genres such as romance novels, neo-slave narratives, and fairy tales. The book tracks Walker’s engagement with narrative as she develops from silhouettes into film, video, and sculpture. A critical discussion gradually transitions from the visual legacy of historical racism to the role that the entertainment industry and its consumers play in the processes of racialization today.

- Focuses on a few key pieces of Walker's

- A great contribution to the existing scholarship on Walker

- Walker's storytelling is compared with various literary genres

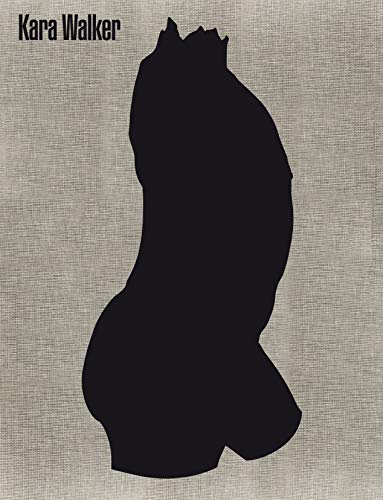

Kara Walker: A Black Hole is Everything a Star Longs to Be (2021) by Anita Haldemann

Featuring beautiful cloth-over-paper binding, this monumental 600-page book offers an intriguing look at Kara Walker’s intensive creative process. This book presents a panorama of over 700 reproductions of the artist’s works, including a never-before-seen private archive of works on paper created between 1992 and 2020.

- A New York Times critics' Best Art Books pick of 2021

- More than 700 works on paper created between 1992 and 2020

- Provides an opportunity to delve into the creative process of Walker

Walker, one of the most celebrated and prominent African American contemporary artists today, functions as a political conscience exposing and excavating the dark side of American history. Through various mediums, including her cut-paper scenes and silhouette wall installations, Walker uses stark visual contrast to depict the horrors of her country, much like Goya, to whom Walker has often been compared. By holding a mirror to history, Walker engages in storytelling about the past, the present, and a possible future.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Kara Walker’s Art About?

In her work, Kara Walker highlights the huge social and economic divides in America today, which are still a product of historical racism. In Walker’s work, fact and fiction are combined in a rich imagination, often resulting in complicated and layered work. In Walker’s multidisciplinary practice, we see hints of sexual violence, inequality, and racism woven into complex narratives, which slowly unfold over time.

Who Influenced Kara Walker?

Walker says Andy Warhol’s art influenced her as a child. Other influences include Robert Colescott, a painter known for his satirical use, and Adrian Piper, a conceptual artist and philosopher.

What Is the Significance of Kara Walker’s Artwork Titles?

By depicting scenes from history and literature, Kara Walker subverts Western history painting and makes it relevant to contemporary society. Walker understands the power of titles to inform her work. She uses long grandiose literary titles to draw attention to her appropriation of this tradition in historical Western painting and the significance of it in her work, which is often satirical.

Chrisél Attewell (b. 1994) is a multidisciplinary artist from South Africa. Her work is research-driven and experimental. Inspired by current socio-ecological concerns, Attewell’s work explores the nuances in people’s connection to the Earth, to other species, and to each other. She works with various mediums, including installation, sculpture, photography, and painting, and prefers natural materials, such as hemp canvas, oil paint, glass, clay, and stone.

She received her BAFA (Fine Arts, Cum Laude) from the University of Pretoria in 2016 and is currently pursuing her MA in Visual Arts at the University of Johannesburg. Her work has been represented locally and internationally in numerous exhibitions, residencies, and art fairs. Attewell was selected as a Sasol New Signatures finalist (2016, 2017) and a Top 100 finalist for the ABSA L’Atelier (2018). Attewell was selected as a 2018 recipient of the Young Female Residency Award, founded by Benon Lutaaya.

Her work was showcased at the 2019 and 2022 Contemporary Istanbul with Berman Contemporary and her latest solo exhibition, titled Sociogenesis: Resilience under Fire, curated by Els van Mourik, was exhibited in 2020 at Berman Contemporary in Johannesburg. Attewell also exhibited at the main section of the 2022 Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Learn more about Chrisél Attwell and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Chrisél, Attewell, “Kara Walker – Interesting Facts About Artist Kara Walker.” Art in Context. November 6, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/kara-walker/

Attewell, C. (2022, 6 November). Kara Walker – Interesting Facts About Artist Kara Walker. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/kara-walker/

Attewell, Chrisél. “Kara Walker – Interesting Facts About Artist Kara Walker.” Art in Context, November 6, 2022. https://artincontext.org/kara-walker/.