Faith Ringgold – An Exploration of the Artistic Life of Faith Ringgold

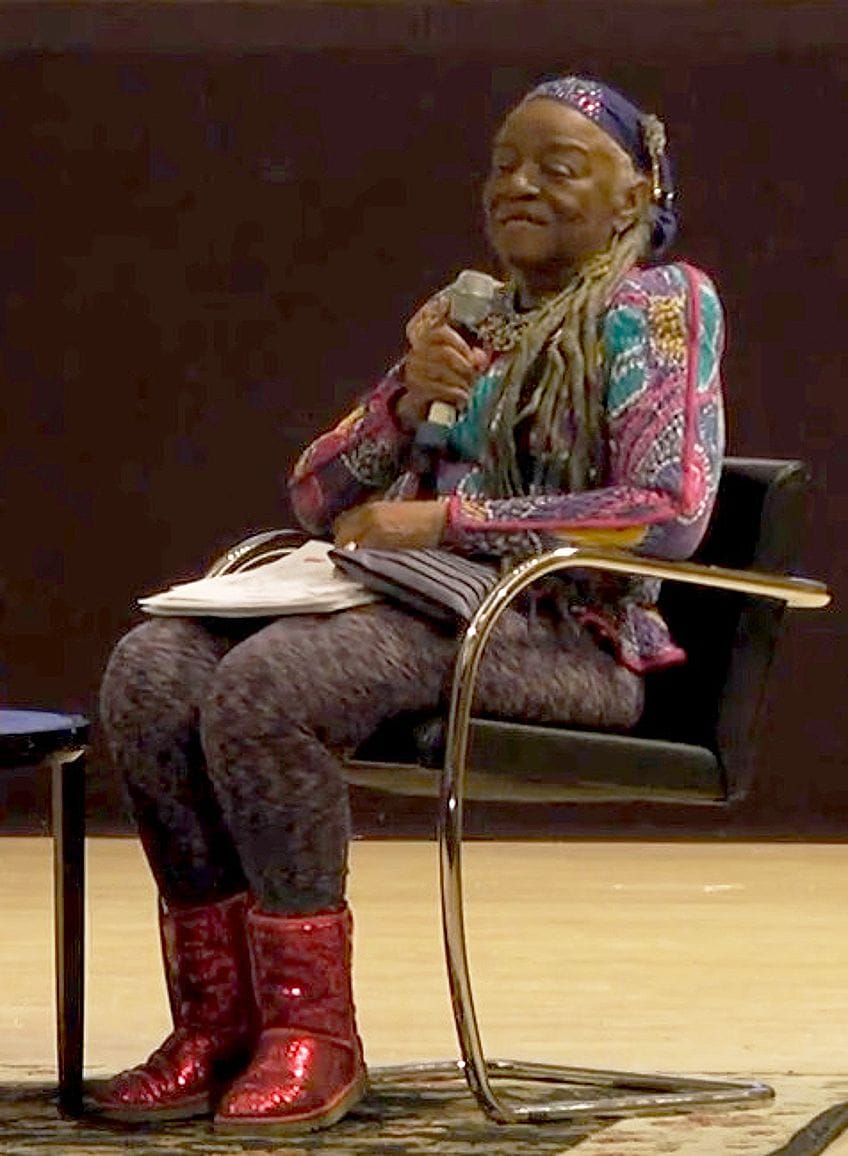

Activist, artist, and author Faith Ringgold has been a voice against racial injustice for 89 years. In mediums from painting, performance art, sculpture, and quilting, Ringgold has used her artistic skill to raise public awareness and communicate her political ideas. Today, Ringgold’s work remains incredibly poignant and more relevant than ever. In this article, we have collated the Faith Ringgold facts that paint a picture of her life as an artist, activist, and performer.

A Brief Faith Ringgold Biography

Faith Ringgold, a sculptor, performer, teacher, and writer, has been a front-runner in political activism throughout her life. From her American People Series, which presented the civil rights movement from the perspective of black women to the Slave Rape series, Ringgold has confronted the oppressive forces of American society head-on. Find out more about this artist below as we present this Faith Ringgold Biography.

Growing Up in Harlem

In 1930, Faith Ringgold was born to a family of five in Harlem. Growing up during the Harlem Renaissance, Ringgold was exposed to all the cultural offerings of this vibrant yet poverty-stricken New York neighborhood. As a child, Ringgold had asthma, so she spent much of her time inside with her mother. As a fashion designer, Ringgold’s mother taught her how to sew and use fabrics creatively.

Ringgold’s passion for creativity continued into her high school education. When she graduated, Ringgold decided she would turn her passion into a career. In 1950, Ringgold began studying at the City College of New York. Unfortunately, the department of liberal arts denied her application, so she studied art education instead.

Ringgold also married Robert Wallace, a musician, in the same year. Two years later, the pair had two daughters, but the marriage did not last long. Seven years after the birth of their children, Ringgold and Wallace divorced as a result of Wallace’s heroin addiction, which ultimately led to his death.

Faith Ringgold Art Career

Following her divorce, Ringgold traveled throughout Europe in the early 1960s. During the 1960s, Ringgold also began to create her first series of political paintings, American People Series (1963-1967). The decade of 1960 to 1970 also saw Ringgold host her first two individual exhibitions in New York at the Spectrum Gallery.

Following her first painted series, Ringgold began to create masks, soft sculptures, and tankas in the 1970s. Ringgold found inspiration for the tankas from a Tibetan style of painting with rich brocaded fabric frames. In her later masked performances of the 1970s and 1980s, Ringgold would use these same techniques of fabric sculpture.

Despite the clear African art influence in Ringgold’s early work, she did not visit Ghana and Nigeria until the late 1970s. The inspiration that Ringgold found in the rich mask traditions in these countries would continue throughout her career.

In 1980, Ringgold made Echoes of Harlem. Ringgold made this quilt in collaboration with Madame Willi Posey, her mother. These quilts were a continuation of her work with tankas, quilted paintings with fabric borders. This quilt was the first work in Ringgold’s new and unique medium. The first narrative quilt by Ringgold was called Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima, and she finished it in 1983. Story quilts like this one were a way for Ringgold to publish her own unedited words.

Ringgold is also famed for the many children’s books she wrote during her career, beginning with the publication of Tar Beach, by Crown. Based on a quilt from her Woman on a Bridge series, this book is illustrated for children. Many of her books won Faith Ringgold awards. In 1991, this book won her the Coretta Scott King award for the best illustrated children’s book.

In 1992, Crown published Aunt Harriet’s Underground Railroad in the Sky. Only a year later, Hyperion Books published Dinner at Aunt Connie’s. This third children’s book was based on Ringgold’s The Dinner Quilt (1986). To date, Faith Ringgold has published 17 books for children, as well as her autobiography. For some time, until 2002, Ringgold worked at the University of California as a professor of art.

Faith Ringgold Art: A Multimedia Exploration of Black Lives in America

Throughout her career, Ringgold has created many multimedia works exploring what it means to be a black person in America. From her children’s books to her confronting paintings, Ringgold represents the power of art in activism.

Faith Ringgold Paintings

After completing her degree, Ringgold began painting in the 1950s. These early works feature flat shapes and figures. Ringgold found inspiration in the styles of Cubism, Impressionism, and African art. While Ringgold did receive a lot of attention for these early paintings, the highly political messages made them difficult to sell.

The underlying messages about racism and micro-aggressions are reflections of Ringgold’s experiences during the Harlem Renaissance.

The American People Series (1963) was Ringgold’s first collection of political paintings. Finding inspiration in the artist Jacob Lawrence, this series explores the American lifestyle as it relates to the Civil Rights Movement. This series of paintings was one of the first representations of the Civil Rights Movement from a black female perspective, and it calls into question the fundamental issues of racism in America.

As a black female artist, Ringgold says that there was nothing else she could bring herself to depict at the time. Other oil paintings by Ringgold, like Watching and Waiting, For Members Only, The Civil Rights Triangle, and Neighbors, all deal with these themes.

As her exhibition for American People Series was beginning, Ringgold began to work on a new series called America Black, or the Black Light Series. In this series, Ringgold experimented with new ways of approaching light and color. White western art, as Ringgold observed, tends to use a lot of white and uses light to emphasize the contrast. Intending to create a “more affirmative black aesthetic”, Ringgold took inspiration from African cultures who use color rather than tonality to emphasize contrast, and who tend to use darker colors.

Ringgold wrapped up her American People Series with large-scale murals like Die, U.S Postage Stamp Commemorating the Advent of Black Power People, and The Flag Is Bleeding. These murals highlight Ringgold’s shift in aesthetic.

A multi-paneled quilted series called the French Collection (1991) explored the myths and truths of modernism. This series investigated possibilities for overcoming the history of oppression faced by African American men and women. The series derives its name from France, the home of modernism at the time. France was also the source of identity-finding for many African Americans.

For the Women’s House (1972)

In the 1970s, Ringgold was commissioned to complete a large-scale mural for the Rikers Island Women’s Facility. The Creative Artists Public Service Program sponsored this piece, which was called For the Women’s House (1972). The composition is anti-carceral and features women in various professions as a positive alternative to incarceration.

Ringgold conducted extensive interviews with the female inmates, and these were the inspiration for the portraits in the mural. The mural’s design separates the portraits into triangular sections to reference the Kuba textile designs from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Many regard this mural as Ringgold’s first feminist work, and it was her first public commission.

Faith Ringgold Self-Portrait (1965)

Completed at the beginning of her career, this Faith Ringgold self-portrait paralleled the rise of radical political movements like Black Power during the 1960s. This painting is typical of Ringgold’s early style, with a flat, hard-edged technique.

The Faith Ringgold self-portrait presents the artist in a determined fashion, with folded arms and a firm gaze. The gesture manages to appear both guarded and gentle. For Ringgold, this self-portrait was a way for her to find herself in and through her art.

Faith Ringgold Quilts

In the early 1970s, Ringgold began to experiment with new mediums, particularly fabric. For Ringgold, using fabric was a way to break free from the European and western artistic tradition that was painting. In 1972, Ringgold and her daughter visited Europe. Ringgold’s daughter, Michele, went to Spain to visit some friends, and Ringgold went to the Netherlands and Germany. While in Amsterdam, Ringgold had a profound experience at the Rijksmuseum, which inspired much of her later work.

When she got back to New York, Ringgold started using features from Nepali paintings in her own work. She began to paint on canvases with soft fabric borders, create soft sculptures and cloth dolls. The first series of Faith Ringgold quilts was The Slave Rape Series which presented an African woman’s experiences of being captured and sold into slavery. Ringgold collaborated on this piece with her mother.

Ringgold’s mother taught her daughter the quilting techniques of her African American roots.

After a failed attempt to publish her autobiography, Ringgold began to use quilting as a method of telling her story. The Echoes of Harlem quilt was the first in this series. Ringgold went on to create numerous quilts, some with text narratives included. Perhaps the most famous Faith Ringgold quilt is Tar Beach, the first part of the Woman on a Bridge series, completed in 1988.

Another of these narrative quilts includes a tribute to Michael Jackson, Who’s Bad? (1988). Who’s Afraid of Aunt Jemima (1983) was a particularly famous quilt, which investigated the stereotypical representations of black women in the media and popular culture. Many of her autobiographical narrative quilts went on to inspire the children’s books she wrote. For example, The Dinner Quilt (1988) was the inspiration for the book Dinner at Aunt Connie’s House, published in 1993 by Hyperion Books.

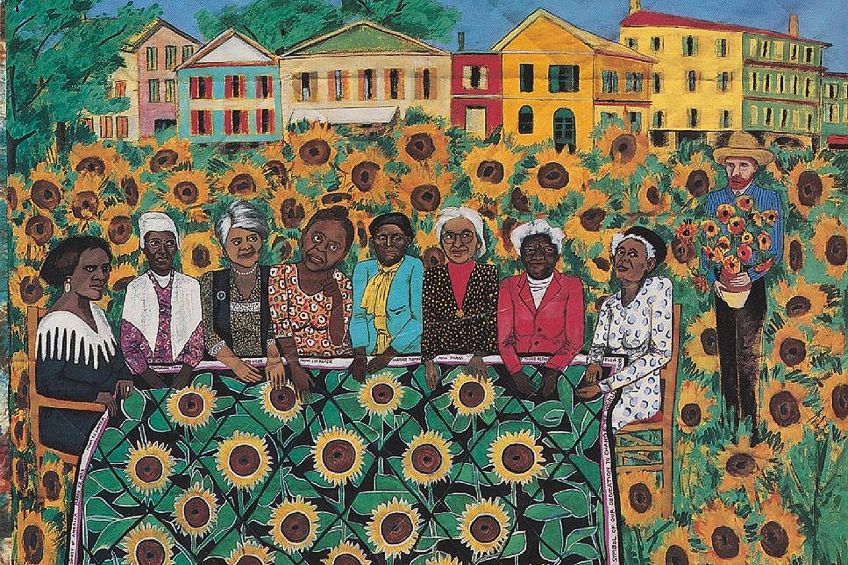

Ringgold’s French Collection also featured a series of narrative quilts. Many of these quilts, like The Sunflower Quilting Bee at Arles, are dedicated to historical African American women who have changed the world. These quilts demonstrate the historical fantasy and immersive power of imaginative childlike storytelling.

Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pounds Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt (1986)

This quilt was completed in 1986 and told the well-known story of a woman desiring to feel good about herself when she fails to live up to the cultural beauty standards. This work is particularly poignant because it considers the relationship between external beauty and intelligence. This Faith Ringgold quilt is the epitome of her autobiographical narrative quilts.

Faith Ringgold Sculpture

In 1973, Ringgold left her job as an art teacher to focus on her art, and she began to experiment with sculpture. Ringgold used this new medium as a means of documenting national events and her local community. Faith Ringgold’s sculptures range from freestanding soft sculpture portraits to the costumed masks she used for many of her performances. Perhaps her most famous collection of Masks is the Witch Mask Series of 11 masks with costumes.

Following her Witch Mask Series collection of masks, Ringgold began to work on a much larger series of 31 sculpted masks. Each of these masks was a commemoration of a woman or young girl that she knew as a child. In addition to the sculpted masks, Ringgold also made soft sculpture portraits. Ringgold created a series of dolls with heads made from painted gourd heads and costumes made in collaboration with her mother.

The sculpted dolls soon led to a series of life-sized soft sculptures beginning with Wilt (1974). Ringgold went through further evolutions in her soft sculpture techniques. Carving foam faces and spray painting them, Ringgold created life-sized “portrait masks” of many people, from the likes of Martin Luther King Jr. to unknown denizens from the Harlem Neighborhood.

Unfortunately, as Ringgold describes in her autobiography, these portraits began to deteriorate and required restoration. To restore them, Ringgold would cover the faces with a cloth and carefully mold them to preserve the likeness.

The Witch Mask Series (1973)

After her students expressed their surprise that Ringgold did not have masks as part of her art practice yet, she began to make them. The Witch Mask Series was one of the first series of sculpted fabric masks that Ringgold created. Created in collaboration with her mother, Ringgold made a series of 11 mask costumes.

Ringgold made these mixed media masks from pieces of painted linen canvas, weaved with beads and raffia for hair. Using long rectangular pieces of cloth, Ringgold created dresses to be worn with the masks and created breasts out of painted gourds.

People could wear these costumes and masks, but they would lend the wearer feminine characteristics. In traditional African rituals, masks and costumes, like the ones Ringgold created, were often worn by men. The masks in this series have a sculptural and spiritual identity and this dual-purpose was essential for Ringgold. Although the masks were highly decorative, they were also made for wearing, and the wearing added to their spiritual and cultural significance.

Wilt (1974)

Wilt was a life-sized sculpture portrait of Wilt Chamberlain, a famed basketball player, with a fictitious white wife and mixed-race daughter. Ringgold created this sculpture following some negative comments by Chamberlain about African American women.

The heads of these sculptures were baked and painted coconut shells, and Ringgold crafted the anatomically correct bodies from foam and rubber. The three sculptures were draped in clothing and hung on invisible fishing lines from the ceiling.

Faith Ringgold Performance Art

The duality of many of Ringgold’s sculpted masks made the transition from sculpture to performance art a natural one. Performance art pieces were abundant during the 1960s and 70s, but this is not where Ringgold found inspiration. Instead, Ringgold looked to the African traditions of combining dance, costumes, music, masks, and storytelling.

In the last three decades of the 20th century, Ringgold created and performed many performance pieces. Many of these pieces were autobiographical, like The Bitter Nest (1985), a masked storytelling piece set in Harlem Renaissance.

In 1986, Ringgold created a performance piece based on her weight loss journey. This particular performance was multidisciplinary. Ringgold used many of her masks and costumes with her quilt Change: Faith Ringgold’s Over 100 Pound Weight Loss Performance Story Quilt. The performance also included dancing and singing. Many of Ringgold’s performance pieces were also interactive. Faith Ringgold would encourage the audience to join her in dance and song.

Although the content of some of her performances may have been controversial, Ringgold did not intend to shock people. Instead, performance art was another way for Ringgold to tell her story.

The Wake and Resurrection of the Bicentennial Negro

Created in response to the 1976 American Bicentennial celebrations, this performance was a narrative exploration of some of the barriers faced by the African American community at the celebration of 200 years of American freedom.

From drug addiction to the dynamics of underlying racism in everyday actions, Ringgold offers a critique of American history where African American people had been slaves for half of the celebrated 200 years of freedom. Ringgold performed this half-an-hour piece in mime with music. Many of her past installations, sculptures, and paintings were also featured in this performance.

Faith Ringgold: Activism Through Art

For Faith Ringgold, awards have never been the driving force behind her art. It is not a surprising Faith Ringgold fact that she has been an activist throughout her illustrious career, and she has worked with many anti-racist and feminist organizations. Ringgold was involved in the founding of the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee with Lucy Lippard and Poppy Johnson in 1968. This committee was involved in protests at the modern art exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art. The protest demanded that female artists account for 50% of the exhibitors.

Not only were female artists excluded from this exhibition, but there were also no African-American artists exhibiting. The members of the committee created disturbances at the museum by chanting about their exclusion, leaving sanitary napkins and raw eggs on the ground, singing, and blowing whistles. In 1970, Ringgold was arrested following her participation in several other protests. Lippard and Ringgold also participated in the Women Artists in Revolution movement.

In 1970, the Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation was founded by Ringgold and her daughter. Four years later, the pair were also founders of the National Black Feminist Organization. Ringgold was also involved in founding the “Where We At” Black Women Artists collective. This women’s art collective was based in New York and associated with the Black Arts Movement. In 1971, the women’s collective put on their first show, featuring soul food as an act of embracing cultural roots. By 1976, the collective of eight artists had grown to 20.

The Coast-to-Coast National Women Artists of Color Projects was founded in 1988. Ringgold and Clarrissa Sligh were founding members of this organization which was involved in showing the works of African American women from across America from 1988 to 1996.

Ringgold wrote the introduction of the catalog for the exhibitions, which was entitled History of Coast to Coast. The catalog included over 100 female artists of color, including short artist statements and photographs of the artists. The catalog includes works by Ringgold, Slight, Beverly Buchanan, Martha Jackson Jarvis, Adrian Poper, Deborah Willis, Emma Amos, Howardena Pindell, Joyce Scott, and Elizabeth Catlett.

The Continuing Significance of Faith Ringgold

Despite the years of activism through her art, it is defeating to know that there is still more work to do. Following the brutal murder of George Floyd at the hands of police on May 25th, 2020, Ringgold’s iconic painting Die from the American People Series seems more poignant than ever. The piece still hangs alongside iconic paintings by Picasso, and Faith Ringgold hopes that it will continue to spark the necessary conversations into the future.

Although so much has changed during Faith Ringgold’s lifetime, the events of the past few years have shone a light on the work that still needs to be done. Faith Ringgold’s art is moving, personal, and political, and remains influential to this day.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Faith Ringgold – An Exploration of the Artistic Life of Faith Ringgold.” Art in Context. March 3, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/faith-ringgold/

Meyer, I. (2021, 3 March). Faith Ringgold – An Exploration of the Artistic Life of Faith Ringgold. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/faith-ringgold/

Meyer, Isabella. “Faith Ringgold – An Exploration of the Artistic Life of Faith Ringgold.” Art in Context, March 3, 2021. https://artincontext.org/faith-ringgold/.