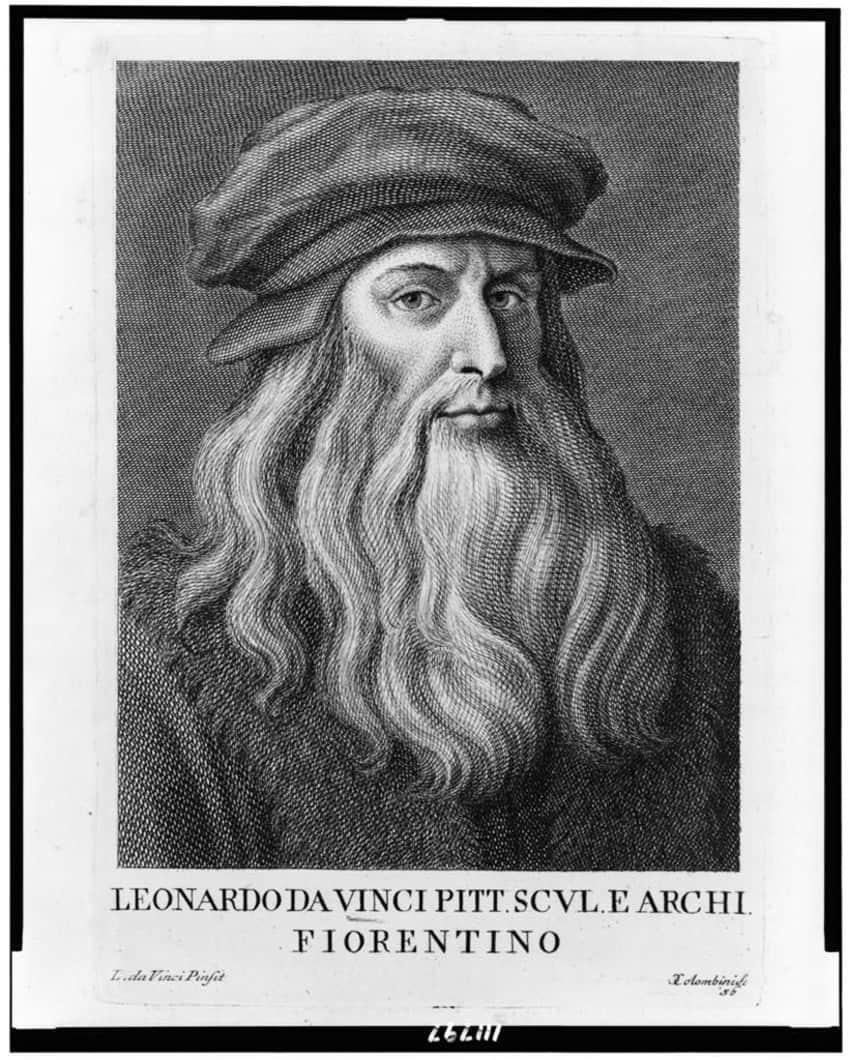

Leonardo da Vinci – The Life and Artworks of Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci was a prime example of the kind of person who, throughout the Italian High Renaissance, was completely committed to studying the humanities in order to continuously improve himself as a member of society. Although Leonardo da Vinci’s accomplishments span many different principles and mediums, he is most well-known for his paintings, such as the Leonardo da Vinci portrait known as the Mona Lisa (1503). So, where was Leonardo da Vinci born? Where did he die? In this article, we will take a look at Leonardo da Vinci’s biography and answer these questions and more.

Table of Contents

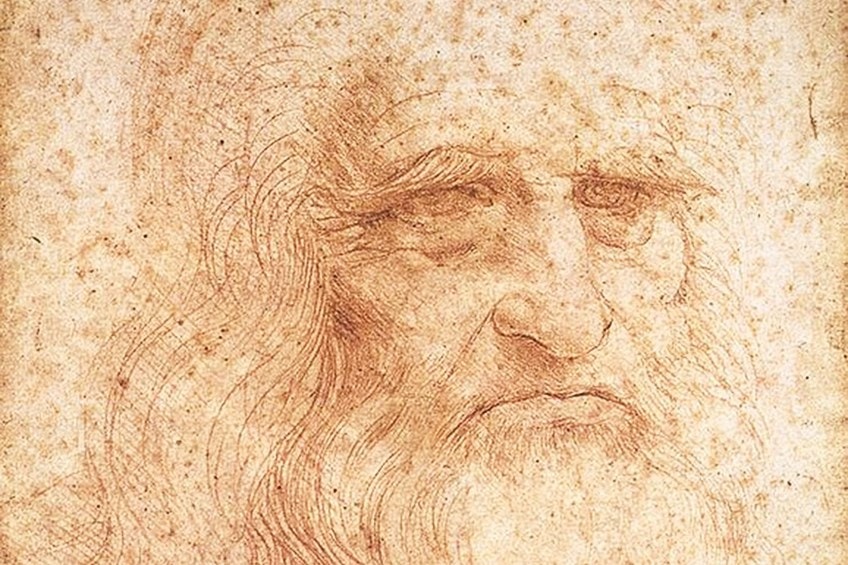

Leonardo da Vinci’s Biography

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 15 April 1452 |

| Date of Death | 2 May 1519 |

| Place of Birth | Anchiano (near Vinci), Tuscany, Florence |

Leonardo da Vinci’s insatiable curiosity and creative imagination used both of his brain’s left and right sides to their full potential to create a number of innovations that were far ahead of their time. The earliest sketches that predicted the helicopter, parachute, and military tank are attributed to him. His journals are almost as well-regarded as his works of art. They feature scientific graphs, sketches, and painting ideas and are a summation of his life’s work and brilliant intellect.

Today, scholars, artists, and scientists from all around the world continue to admire and study them.

Childhood and Education

In a hamlet close to the Tuscan town of Vinci, Leonardo da Vinci – one of the most talented and creative people in history – was born in 1452. The son of a Florentine attorney named Piero da Vinci and a poor farm girl named Caterina, he was raised by his grandfather on the family estate in Anchiano. Leonardo da Vinci was close to Albiera, a 16-year-old girl his father wedded but who passed away early.

Leonardo da Vinci was the eldest of 12 children, and his family never treated him any differently for being born out of wedlock.

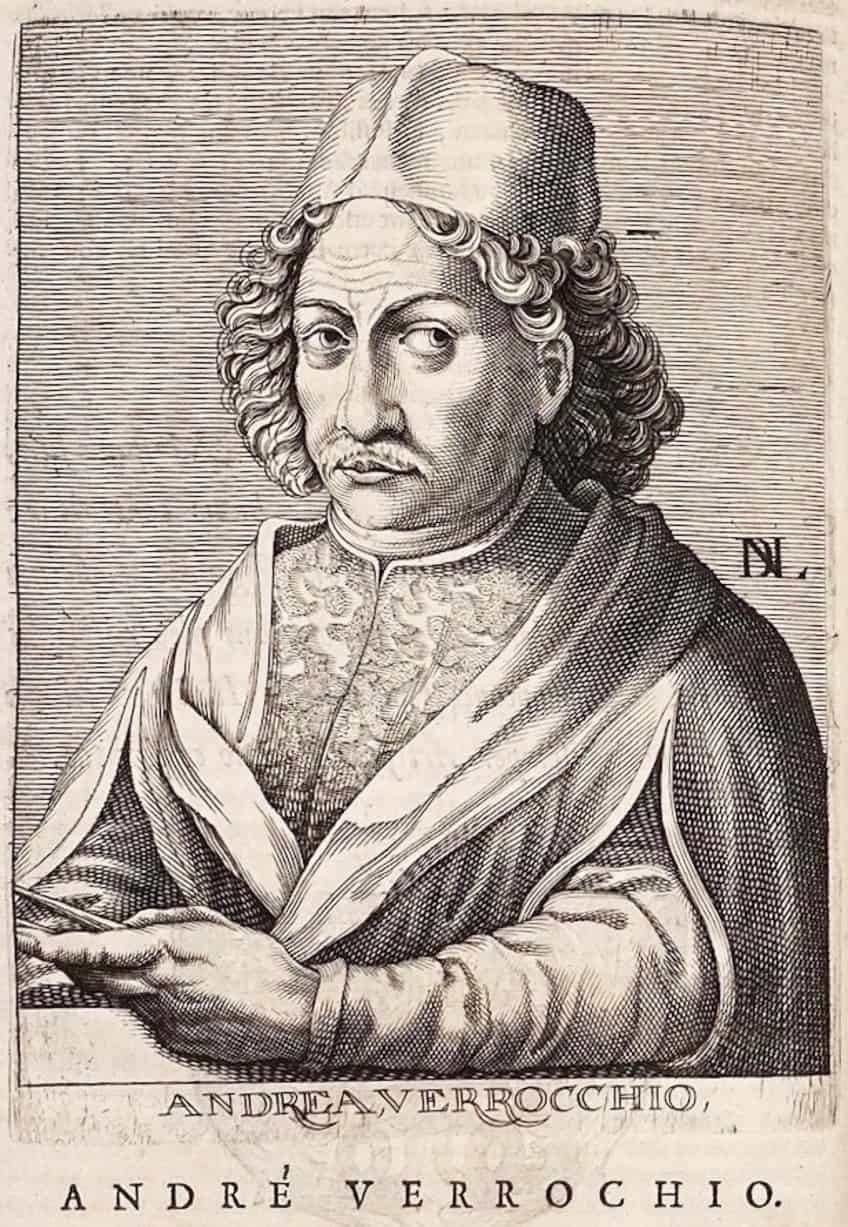

Early Training and Work

Leonardo da Vinci relocated to Florence at the age of 14 to pursue a traineeship with Andrea del Verrocchio, a painter who had studied under Donatello, a prodigy of the Early Renaissance. Verrocchio was a significant artist at the court of the Medici, a wealthy family that is sometimes credited with fostering the Renaissance through its lavish support of the arts and political participation. Pietro Perugino, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Lorenzo de Credi were among the many outstanding young artists who were drawn to Florence, an important creative hub in Renaissance Italy.

Leonardo da Vinci’s ability to start his apprenticeship in such a famous art studio is a sign of his father’s clout in the community.

In order to completely comprehend man’s role in the world, artists of this era immersed themselves in the humanities. Leonardo da Vinci had considerable mentoring from Verrocchio, who helped to develop his early talent. He became interested in biology, architecture, chemistry, arithmetic, and engineering in addition to sketching, painting, and sculpting.

This schooling helped him develop a keen imagination that subsequently led to the design of wonderful inventions, as seen by the numerous sketches of mechanical devices and military weaponry that serve to maintain his image as a genius today.

The production of Verrocchio’s workshop would have been a joint effort between the apprentices and the master, as was customary at the period. Art historians, such as Giorgio Vasari, believe that some paintings attributed to Verrocchio really show traces of Da Vinci’s softer brushstrokes contrasted with the heavier hand of Verrocchio. After serving as an apprentice for six years, Da Vinci joined the Guild of St. Luke, an organization of Florentine painters and physicians, in 1472. Although his father provided him with a workshop of his own, Da Vinci spent the following four years working as an assistant at Verrocchio’s workshop.

Leonardo da Vinci was suspected of sodomy in 1476 together with three other men, but due to a lack of supporting evidence, he was exonerated. This is sometimes linked to the fact that Leonardo da Vinci’s associates hailed from wealthy families. At the time, homosexuality was against the law and could result in death as well as jail and public disgrace. He may have kept a low profile during the following several years, about which not much is known, due to the consequence that came after such a terrible incident.

The monks of San Donato a Scopeto provided him with one of his first solo contracts to depict the Adoration of the Magi between 1480 and 1482. After accepting a job offer from the Duke of Milan to serve in his court, Da Vinci would pause work on the commission to relocate to Milan. Many theories have been put up as to why the shift to Milan was required at this particular time, some of which refer to the sodomy charge from a few years before.

However, it is more probable that Da Vinci was lured by the extravagant Milanese Court’s invitation and the chance to advance his name and profession.

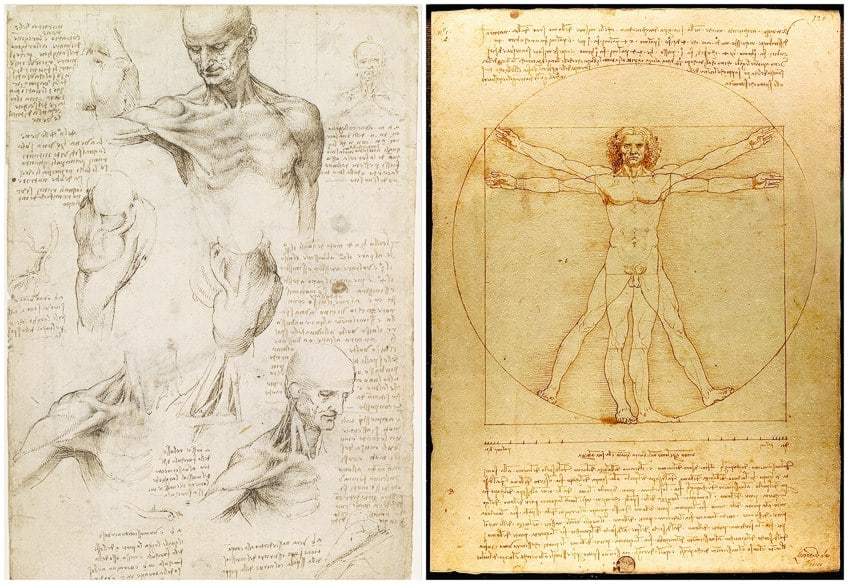

Mature Period

From 1482 through 1499, Da Vinci was employed by the Milanese Court. He was a well-known perfectionist who devoted a lot of time to studying human anatomy, especially how people’s bodies moved, were assembled, and were proportioned, how they interacted with one another during social interactions and communication, as well as how they expressed themselves through gestures.

This was undoubtedly a laborious process, which may explain in part why there are so few completed works despite an extraordinary amount of intricately detailed sketches and drawings that served as full-scale preliminary drawings for canvases.

In addition to demonstrating his unmatched powers of observation, these sketches also demonstrate his aptitude as an artist for deciphering and expressing human emotion.

Development of Techniques

Leonardo da Vinci dabbled with profoundly novel and distinctive painting approaches throughout this time. The artist is renowned for a number of skills, including his ability to produce the smokey effect known as sfumato.

He created a method that enabled margins of color and outline to merge together to accentuate the gentle variation of skin and material as well as the astonishing translucence of hard surfaces like crystal or the textures of hair through his in-depth understanding of brushstrokes and glazes.

Leonardo da Vinci’s themes and characters had an intimate genuineness that seemed to reflect reality in novel ways. Da Vinci’s painting, Salvator Mundi (1500), in which he depicts an orb, is a good illustration of this.

However, some of his experiments, like many other ground-breaking breakthroughs, would only become problematic afterward. The Last Supper (1498), one of his greatest fresco masterpieces of the time, was the most outstanding.

However, Da Vinci had used oil paints on wet plaster to create the sfumato aesthetic, which finally caused the pigment to peel off the refectory wall of the monastery of Santa Maria del Grazie in Milan.

He was sent on a mission to meet the powerful Matthias Corvinus, King of Hungary, in 1485 on behalf of the duke. While there, he was required to use his rigorous creative abilities to start preparing court festivals as well as architectural and engineering projects, such as the Milan cathedral’s dome design.

Continuing Work for Monarchs

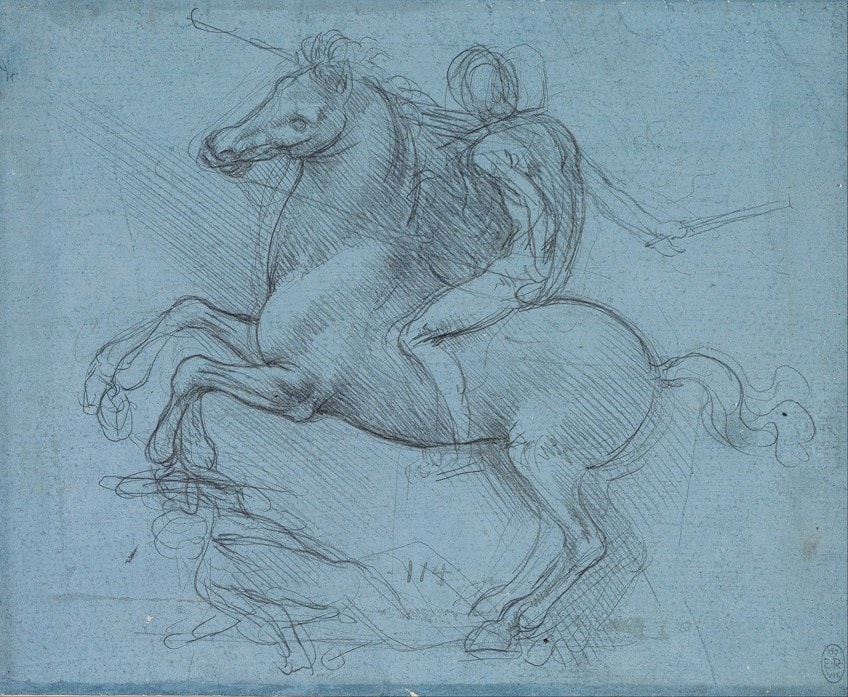

Leonardo da Vinci was commissioned to produce a five-meter-high equine bronze sculpture named Gran Cavallo in 1482 honoring the founder of the Sforza family as his final unfinished project before departing Milan.

During Emperor Maximilian’s wedding to Bianca Maria Sforza in 1503, a clay model of the planned sculpture was presented, stressing the significance of the upcoming work.

However, the project was never completed, and the victorious French Army used the figure for target practice after taking Milan in 1499. According to legend, the bronze intended for the sculpture was reused for cannon production during the inevitable failure of Charles VIII’s defense of Milan during the war with France.

After the 1499 French invasion and the fall of the Duke of Milan, Da Vinci traveled to Venice with Salai, his long-time companion, and helper who had lived with Da Vinci since he was 10 years old and stayed with him until his death. Da Vinci worked as a military engineer at Venice, where his major task was to construct naval defensive systems for the city, which was under threat from Turkish military advancements in Europe. He returned to Florence in 1500, where he resided as a visitor of the Servite monks in the abbey of Santissima Annunziata with his partner.

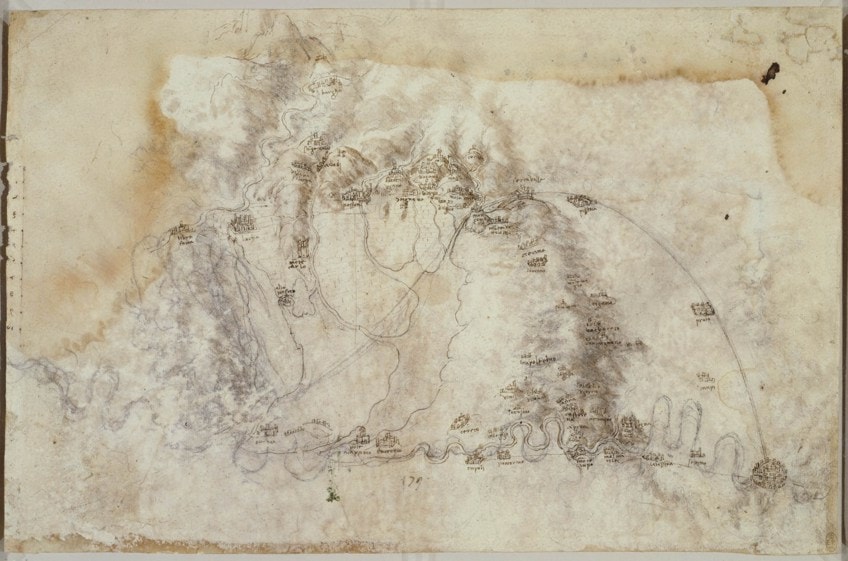

Da Vinci obtained employment at the Court of Cesare Borgia, a prominent member of a powerful family, in addition to being the son of Pope Alexander VI and leader of the papal army, in 1502. As a military engineer, he followed Borgia on his travels around Italy.

His responsibilities included creating maps to help in military defense and building a dam to assure an unbroken flow of water from the River Arno to the canals.

Interest in Science

During the river diversion project, he met Niccolò Machiavelli, a prominent writer, and political analyst for Florence at the time. Leonardo da Vinci is considered to have introduced Machiavelli to the notions of applied science.

Thus, Da Vinci seemed to have made a significant effect on the man who would go on to be referred to as the founder of modern political science.

In 1503, Da Vinci came to Florence for the second time and was greeted as a superstar when he rejoined the Guild of St Luke. This homecoming triggered one of the artist’s most creative years of artwork, such as preparatory work on his Virgin and Child with Saint Anne (1519).

Da Vinci returned to Milan in 1508, where he spent the following five years under the sponsorship of the French Governor of Milan, Charles d’Amboise, and King Louis XII. During this time, he was highly involved in scientific pursuits such as anatomical, mathematical, mechanical, and botanical research, as well as the development of his renowned flying machine.

During this time, notable projects included the development of a villa for Charles, bridge construction, and a project to develop a canal between Lake Como and Milan.

He also invented effective military weapons, including an early prototype of the machine gun and his well-known huge crossbow. During this period, Da Vinci also met his apprentice Francesco Melzi, who became his partner until his death. It’s possible that at this moment in his career and life that Da Vinci was eventually able to live openly as a homosexual man, his successes and renown offering a safe haven from the type of painful and punishing stigmatizing he faced in his youth.

Late Period

After the French were temporarily expelled from Milan in 1513, Da Vinci traveled to Rome and spent the next three years there. He was called to the attention of French King François I, who gave him a permanent post as the French Royal Court’s principal artist and engineer. He was sent to Clos Lucé, near the king’s Château d’Amboise. François I, a significant character in the French Renaissance, would not only become the kind of patron Da Vinci required in his later years, requiring little of Da Vinci’s time but he was also said to be a good friend of the artist. “The King was accustomed to regularly and cordially seeing him,” Vasari said of the bond.

Leonardo da Vinci spent much of his last years organizing his scientific papers and notes rather than painting.

His final picture, St John the Baptist (1513), was most likely completed around this time. This collection of notes, reflecting a lifetime’s worth of outstanding research and aptitude throughout a wide range of fields, has proven to be his most lasting legacy.

His views on mathematics, architecture, engineering, human anatomy, and physics, as well as his perspective on art and Humanism, demonstrated a depth of brilliance that earned him the title of real genius.

Leonardo da Vinci passed away on the 2nd of May, 1519, in Clos Lucé, leaving his artistic and academic assets to his partner, Francesco Melzi. Salai and his brothers shared ownership of his vines. The mythical narrative of François I attending his death epitomizes the veneration with which he was held.

“Leonardo da Vinci breathed his last breath in the arms of the monarch,” according to Vasari.

Leonardo da Vinci was buried at the church of St Florentin at the Chateau d’Amboise, but the structure was damaged due to the effects of the French Revolution. While it is thought he was reburied at the smaller chapel of St Hubert in Amboise, the exact site is unknown.

Da Vinci’s Legacy

It is difficult to sum up Leonardo da Vinci’s legacy in a few words. He perfected his creative skills. The gentle blurring effect in his sfumato approach, his utilization of the vanishing point, his mastery of the interplay between dark and light in chiaroscuro, and his mysterious facial expressions gave his works a captivating and lifelike aspect that had never been seen before.

Although the majority of his painting centered on religion and portraiture during the High Renaissance, which marked the end of the medieval era in Western culture, it was his skills, along with his masterful composition, that had the most effect on Western art.

Indeed, the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper are still among the world’s most known and iconic masterpieces of art, constantly reproduced on prints and firmly established in current popular culture as pieces of eternal historical importance.

But what about his innovations, anatomic studies, topographical sketches, and technical, industrial, and architectural accomplishments? While many of his innovations, such as the helicopter, flying machine, and parachute, stayed in concept form and were impractical in practice, Da Vinci’s inquiring mind was recognized as being centuries ahead of its time.

The same can be said for the precision of his figure drawings, his early inquiry into topography, interest in blood circulation, and other mechanical engineering wonders.

This is not to forget his contributions to precise time-keeping, or the bobbin winder, which at the time had a significant effect on the local industry. His research towards improving military weapons also ushered in the tanks and guns that are so well-known to us today.

Leonardo da Vinci’s Accomplishments

Invention, art, science, architecture, music, engineering, mathematics, literature, geology, astronomy, anatomy, writing, botany, history, and cartography are just a few of the disciplines where Leonardo da Vinci excelled.

Learning never exhausts the intellect, according to a quote attributed to him.

Despite his extensive excursions into other fields of specialization, Da Vinci is most known as a painter. Some of his paintings, like Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait, the Mona Lisa, have continuously been considered ageless and universally famous.

Early Renaissance principles such as chiaroscuro, linear perspective, naturalism, and emotional expressionism were influenced by his contributions to the aesthetics and methods of High Renaissance painting.

With his careful technique and the use of innovative methods, he outperformed many previous painters, such as with his sfumato method, his new approach to combining glazes that produced works that were so lifelike, it was as if his figures lived from within the pictorial plane.

Notable Leonardo da Vinci Artworks

Now that we have covered Leonardo da Vinci’s biography, let us take a look at a few of his most noteworthy artworks. This is just a list as we will also have an article featuring his works in more depth. We all know about Leonardo da Vinci’s portrait Mona Lisa, but let’s see what else he is known for:

| Artwork | Date | Medium | Location |

| Virgin of the Rocks | 1483 – 1508 | Oil on wood transferred to canvas | Musée du Louvre, Paris |

| The Vitruvian Man | 1485 | Pen and ink on paper | Accademia, Venice, Italy |

| The Last Supper | 1498 | Fresco | Convent of Sta. Maria delle Grazie, Milan, Italy |

| The Virgin and Child with St. Anne and St. John the Baptist | 1500 | Charcoal and chalk drawing on paper | The National Gallery, London |

| Salvatore Mundi | 1500 | Oil on wood panel | Louvre, Abu Dhabi |

| Mona Lisa | 1503 | Oil on wood panel | Musée du Louvre, Paris |

Recommended Reading

If you would like to learn more about Leonardo da Vinci’s accomplishments and art, then we can recommend checking out these books. They provide even more insight into Leonardo da Vinci’s biography and artworks.

Whether you are already a fan of his works, or just being introduced to this master, there is no better way to celebrate his works than with a book.

Leonardo da Vinci: Notebooks (2008) by Leonardo da Vinci

The majority of what is understood about Leonardo da Vinci comes from his famous notebooks, compiled around 1487 to 1490. Approximately 6,000 pages of notes and sketches have survived, representing approximately one-fifth of the actual work he created. He chronicled his studies on the flow of water and the development of rocks, the physics of aviation and optics, anatomy, building, painting, and sculpture in these volumes with an artist’s keen eye and a scientist’s curiosity.

- A compilation of the famous notebooks kept by Leonardo da Vinci

- Includes some 6,000 sheets of the artist's notes and drawings

- Fully updated edition with a preface by Da Vinci expert Martin Kemp

The Complete Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci (2016) by Leonardo da Vinci

Many people see Leonardo da Vinci, possibly the leading figure of the Renaissance, as a man of mystery. Despite the fact that we have an unrivaled collection of records that illustrate his intellectual interests, processes, and innermost convictions. This compilation allows the reader insight into hundreds of his notes, drawings, doodles, musings, even book lists, and financial information.

- Includes all known Da Vinci papers as of the mid-19th century

- Illuminates the artist's thought processes, interests, and beliefs

- With hundreds of pages of notes, sketches, musings, and more

That concludes our exploration of the incredibly talented Renaissance man known to the world as Leonardo da Vinci. A man of many skills, Leonardo da Vinci’s accomplishments have made him one of the most well-known figures in human history. Yet, it is his art for which he is most well-known, specifically his paintings.

Take a look at our Leonardo da Vinci art webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Where Was Leonardo da Vinci Born?

Leonardo da Vinci, one of human history’s most gifted and innovative prodigies, was born in 1452 in a small village near the town of Vinci. He grew up in a very large family and was the oldest of 12 siblings. He then moved to Florence when he was only 14 years of age. He passed away on the 2nd of May, 1519.

What Was Leonardo da Vinci Known For?

He had many talents and interests and was an exceptionally intelligent individual. Yet, it was painting for which he was most renowned. Besides that, he also showed an interest in architecture, biology, science, history, mathematics, maps, and countless other fields of study. His contribution to the principles and techniques of High Renaissance painting inspired early Renaissance ideas such as chiaroscuro, linear perspective, realism, and emotional expressionism. Many of his artworks have been regarded as timeless.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Leonardo da Vinci – The Life and Artworks of Leonardo da Vinci.” Art in Context. October 27, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/leonardo-da-vinci/

Meyer, I. (2022, 27 October). Leonardo da Vinci – The Life and Artworks of Leonardo da Vinci. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/leonardo-da-vinci/

Meyer, Isabella. “Leonardo da Vinci – The Life and Artworks of Leonardo da Vinci.” Art in Context, October 27, 2022. https://artincontext.org/leonardo-da-vinci/.