Famous Paintings at The Met – The Best Met Museum Highlights

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, often referred to as “The Met”, is home to a collection of more than two million objects, making it the largest art museum in the United States and the western hemisphere in general. The world-renowned museum is located along Central Park’s eastern border in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, at 1000 Fifth Avenue. The Metropolitan Museum of Art officially opened to the public on February 20th, 1872. The museum’s collection is incredibly diverse, including a wide variety of objects and artifacts from all around the world, from classical antiquity and Ancient Egypt to paintings by virtually every major European artist throughout history. With this large and expansive collection, it can be difficult to navigate what Metropolitan Museum of Art artworks are a must-see. Here is a list of the most well-known and famous paintings at The Met.

10 Must-See Artworks and Paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art

With its wide range of artwork from a variety of ages and movements, the Metropolitan Museum of Art can be overwhelming for a visitor. Below is a list of Met Museum highlights; with 10 of the most well-known and praised works of art and paintings in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Madonna and Child Enthroned With Saints (1504) by Raphael

| Title | Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints |

| Artist | Raphaello Sanzio (1483 – 1520) |

| Medium | Tempera |

| Dimensions (cm) | 172.4 x 172.4 |

| Date Created | 1504 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

A painting by the Italian High Renaissance master Raphael, The Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints, also known as the Colonna Altarpiece, was created between 1503 and 1505. As this piece of Met art is the only altarpiece by Raphael that can be found in the United States, it is certainly a Met Museum highlight.

Around 1504 to 1505, Raphael created this altarpiece for the Sant’ Antonio Franciscan convent in Perugia.

It was displayed in a section of the cathedral designated for nuns, who may have insisted on its traditional features, like the Christ Child’s ornate dress. Raphael had only started studying recent works by Fra Bartolomeo and Leonardo da Vinci in Florence, whereas the hefty male saints look to the future. The nuns sold their altarpiece in 1678, and when J. Pierpont Morgan bought it at the turn of the 20th century, there was a frenzied reaction from the press.

Mary sitting on the throne is a symbolic gesture among Catholic Church believers because she is considered the savior of the world. The Virgin Mary sitting on a throne is an iconic image within the Catholic religion, which views her as the savior of the world, being the mother of Christ.

While the benediction is taking place in the square portion of the artwork, the semi-circle canopy portrays the godly realm, complete with God and two angels, as seen in the distance with hills, a tower, and general greenery. The work also features Saint Peter, Catherine, Lucy, Saint Paul, the young John the Baptist, and the young Jesus depicted sitting on the throne. John the Baptist, who is at Mary’s feet, is being blessed by Jesus, who is seated on her lap. The benediction is likely being read by the other four saints who are gathered around the throne.

On a 172.4- x 172.4-cm frame, the artwork was created on wood using oil and gold.

Three Predellas made up the entire altarpiece: The Procession to Calvary (National Gallery, London), The Agony in the Garden (Morgan Library, New York), and the Pietà (Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, London). Raphael used his expertise in architecture to apply geometry to this grand painting, despite the more organic, free-flowing paintings of the period. This can be seen in the throne design, the gap between Saint Peter and Saint Paul and the background, and the painting of the throne steps.

Venus And the Lute Player (1565 – 1570) by Titian

| Title | Venus and the Lute Player |

| Artist | Tiziano Vecelli (1488 – 1576) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 165.1 x 209.6 |

| Date Created | 1565 – 1570 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Venus and the Lute Player (1565-1570) was created by artist Tiziano Vecelli, also known as Titian. Oil was used to create this work of Met art on canvas sometime between 1565 and 1570. The artwork was created in a manner resembling a portrait, depicting Venus, the Roman goddess of love being serenaded by the lute player.

This painting is said to be the culmination of the artist’s interest in the theme of the reclining nude goddess, existing in two versions. The first, more finished version, is housed in Cambridge, while the second version, which remained in Vecelli’s studio as a ricordo, a first compositional draft, is on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The star of the artwork, the goddess of love herself, is shown interrupting her music as Cupid crowns her with a wreath of flowers.

She is being admired by a well-dressed young man who is playing the lute, which is the traditional instrument used in love madrigals. Nymphs and Satyrs dance to the sounds of a shepherd in the background. This amusing theme was painted several times by Titian. With the exception of the artist’s entirely painted background landscape, this one was left incomplete. These images appear to primarily highlight sensory pleasures, contrary to what was originally thought to be their allusion to current discussions about whether “seeing” or “listening” is the primary method for appreciating beauty.

There is still more dimension to Titian’s work, in addition to describing the unique relationship between the musician and the goddess, it also directly addresses the viewer.

It is clear that the luxuriant nude is turned frontally for the viewer’s enjoyment via deliberate trickery. Furthermore, the viola da gamba, which is poised as a repoussoir (an object in two-dimensional painting that creates the sense of depth by directing the viewer’s eye) instrument in the lower right corner of the image and extends beyond the frame, waiting for its player, subtly urges us to attend the concert and fully take part in the admiring perception of beauty.

Aristotle With a Bust of Homer (1653) by Rembrandt

| Title | Aristotle with a Bust of Homer |

| Artist | Rembrandt van Rijn (1606 – 1669) |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 143.5 x 136.5 |

| Date Created | 1653 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Aristotle With a Bust of Homer (1653) also known as Aristotle Contemplating a Bust of Homer, is an oil-on-canvas painting by Rembrandt and is certainly a must-see Met Museum highlight. The artwork depicts Ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle looking at a bust of Homer, an ancient poet and the fictitious author of The Iliad (8th century BC) and Odyssey (7th century BC). Aristotle is depicted wearing a gold chain and looking at a carved figure of Homer in the oil-on-canvas piece, which was made on request for the collection of Don Antonio Ruffo, a nobleman from Sicily. Several collectors bought and sold it before the Metropolitan Museum of Art finally acquired it.

Numerous historians and scholars have offered various interpretations of Rembrandt’s theme in response to the mysterious tone of the picture.

This painting captures Rembrandt’s contemplation on the nature of fame. With the opulently attired Aristotle’s palm resting thoughtfully on a bust of Homer, the epic poet who had achieved literary immortality with his Iliad and Odyssey centuries earlier.

The stunning depiction of Alexander the Great on Aristotle’s gold medallion suggests that the philosopher is contrasting his own material success with Homer’s everlasting accomplishment. The piece was created for the patron at a time when Rembrandt’s distinctive style, with its dark palette and almost sculptural layering of paint, was starting to go out of favor in Amsterdam, despite the fact that it had come to be seen as quintessentially Dutch.

The piece is especially interesting from a metatextual perspective, with the viewer admiring the figure of Aristotle as he does the same with the bust of Homer. The work makes use of the chiaroscuro technique, with the face of Aristotle contrasting with the dark background.

The work could be interpreted as a tale of morality in that Aristotle, the successful, well-dressed courtier, envies Homer, the blind but free artist. Another interpretation is that Aristotle and Homer represent science and art respectively, with science deferring to art. But whatever interpretations are theorized, this painting has remained one of the greatest and most mysterious in the world, ensnaring viewers in its thoughtful, glowing, pitch-black, image.

The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David

| Title | The Death of Socrates |

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David (1748 – 1825) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 129.5 x 196.2 |

| Date Created | 1787 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

The Death of Socrates is considered to be one of the great works of Neoclassic art, an art movement that gained prominence in the 1780s. This movement was known for depicting subjects from the Classical age, such as the execution of Ancient Greek philosopher Socrates, as told by Plato in his book, Phaedo (360 BC).

In this piece, the famed philosopher’s final moments are shown. It is said that Socrates was found guilty of corrupting the youth and denying the gods in Ancient Athens.

Socrates had two choices: renounce his principles or consume the deadly hemlock poison. He chose the latter and gave his life in defense of his ideas. Socrates confronts his death head-on rather than running away when the chance presents itself and utilizes this decision as a final lesson for his students and followers. The Phaedo, Plato’s fourth and final dialogue to describe Socrates’ dying days—which are also covered in Euthyphro (399-395 BC), Apology (date unknown), and Crito (399 BC)—depicts the philosopher’s final days.

The Death of Socrates depicts the great philosopher as a stoic elderly man robed in white, who is sitting upright on a bed. His left hand is making a gesture in the air as his right hand is extended over the cup of poison. He is surrounded by his devoted followers and students, all of whom are visibly upset and distressed. The young man who is giving him the cup is facing away and has his face buried in his hand. A second man grips Socrates’ thigh and begs him not to consume the poison.

At the foot of the bed, a second elderly man is seated. This is meant to represent Plato, Socrates’ most well-known pupil, slumped over and gazing into his lap. Through the arch in the back wall, two more men may be seen to the left, while Socrates’ wife Xanthippe, who had been dismissed by her husband earlier, casts a longing glance back at the scene from the stairwell in the background.

David’s use of color in this painting adds a great deal of emotion.

The dark red robe of the man holding the poison cup, usually seen as being offered to Socrates rather than receiving it after Socrates had swallowed its contents, is the painting’s focal point. The tones of red in the painting’s margins are more subdued and become more intense towards the center. Socrates and Plato, the only two serene figures, are dressed in a striking bluish-white. This painting’s more subdued color scheme may also be a response to those who criticized David’s Oath of the Horatii (1784), dubbing its use of color “garish.

Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) by Emanuel Leutze

| Title | Washington Crossing the Delaware |

| Artist | Emanuel Leutze (1816 – 1868) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 378.5 x 647.7 cm |

| Date Created | 1851 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

One of the most famous paintings at the Met, Washington Crossing the Delaware is a historical painting created by German-American artist Emanuel Leutze. The famous piece of Met art depicts the moment in which George Washington crossed the Delaware River with the continental army on December 25 and 26 of the year 1776 during the American Revolutionary War. This surprising action was the first move in a successful surprise attack against the Hessian forces at the Battle of Trenton in New Jersey, which was a key moment in the war.

The first artwork was created by Leutze in 1849, just after the failure of Germany’s own revolution.

Eventually, during a World War II Allied bombing strike, this original canvas was destroyed in the German city of Bremen. In 1850, the artist started work on the second iteration of Washington Crossing the Delaware. In October 1851, a gallery in New York hosted the display of this later picture. Wealthy entrepreneur Marshall O. Roberts bought the piece for the then-staggering sum of $10,000 two years later. In 1897, it was given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The brilliance of Washington Crossing the Delaware is in its vast scale, measuring 378.5 by 647.7 cm. This grand size creates a great experience for the viewer, with the painting’s composition matching the significant moment in history it expresses. While Washington is the focal figure of the piece, Leutze also filled the boat with several soldiers, including two blue-coated Continental officers, and nine men who appear to be militia members.

This is a very diverse set of men, one of which is African-American, another is wearing a checkerboard bonnet that could represent Scotland, and another wears moccasins, a hat, and pants known to be worn by the Native Americans. Leutze’s decision to make the American side of the war so inclusive is certainly purposeful, expressing the colonial cause in the war for independence from the oppressive force of Britain.

What is interesting to note is that Leutze took some creative license in his work, such as the iconic stars and stripes American flag included in the painting despite not being used until September 1777. The event also historically took place at night, while Leutze’s work shows a late daytime scene.

The Ballet Class (1874) by Edgar Degas

| Title | The Ballet Class |

| Artist | Edgar Degas (1834 – 1917) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 83.5 x 77.2 |

| Date Created | 1874 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

The Ballet Class by Edgar Degas is an example of an Impressionist artwork, created in 1874. The renowned piece is a part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection, on display at Gallery 815. It is widely known as one of Degas’ most ambitious works relating to the subject of dance, depicting the fictitious setting of a dance class being taught by renowned ballet instructor Jules Perrot in the former Paris Opera, which had burned down the year before.

The Guillaume Tell poster hanging on the wall is a memorial to Jean-Baptiste Faure, the opera singer who had commissioned the piece.

The piece was created alongside The Dance Class (1874), both of which were originally on display at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. There are more than 20 figures in both, ballerinas and their mothers, with the dance instructor as the main focus of each piece.

Opera baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure commissioned the painting in 1873, with Degas’ paintings making up a sizable portion of Faure’s art collection. The Impressionists’ second show took place in 1876 after Degas finished the painting for Faure in 1874. The picture was contributed to the exhibition by the art collector. The artwork was also known as Examen de danse.

Degas was known for his use of color, and this can be seen in “The Ballet Class” in the delicate pinks, whites, and blues seen on the dancers.

Degas presents the room in neutral tones; there are no bold pops of color, and the composition is visually pleasing. The walls look to be an earthy green, while the floor is an earthy brown. The foreground instruments and the wooden frame of the mirror are darker brown while the ballerinas’ white costumes seem to rule the scene, with the few hues of pink and blue coming from their ribbons. Despite depicting an almost Realist scene, of an everyday scenario, Degas’ use of color, form, and composition creates a rich sensory experience for the viewer.

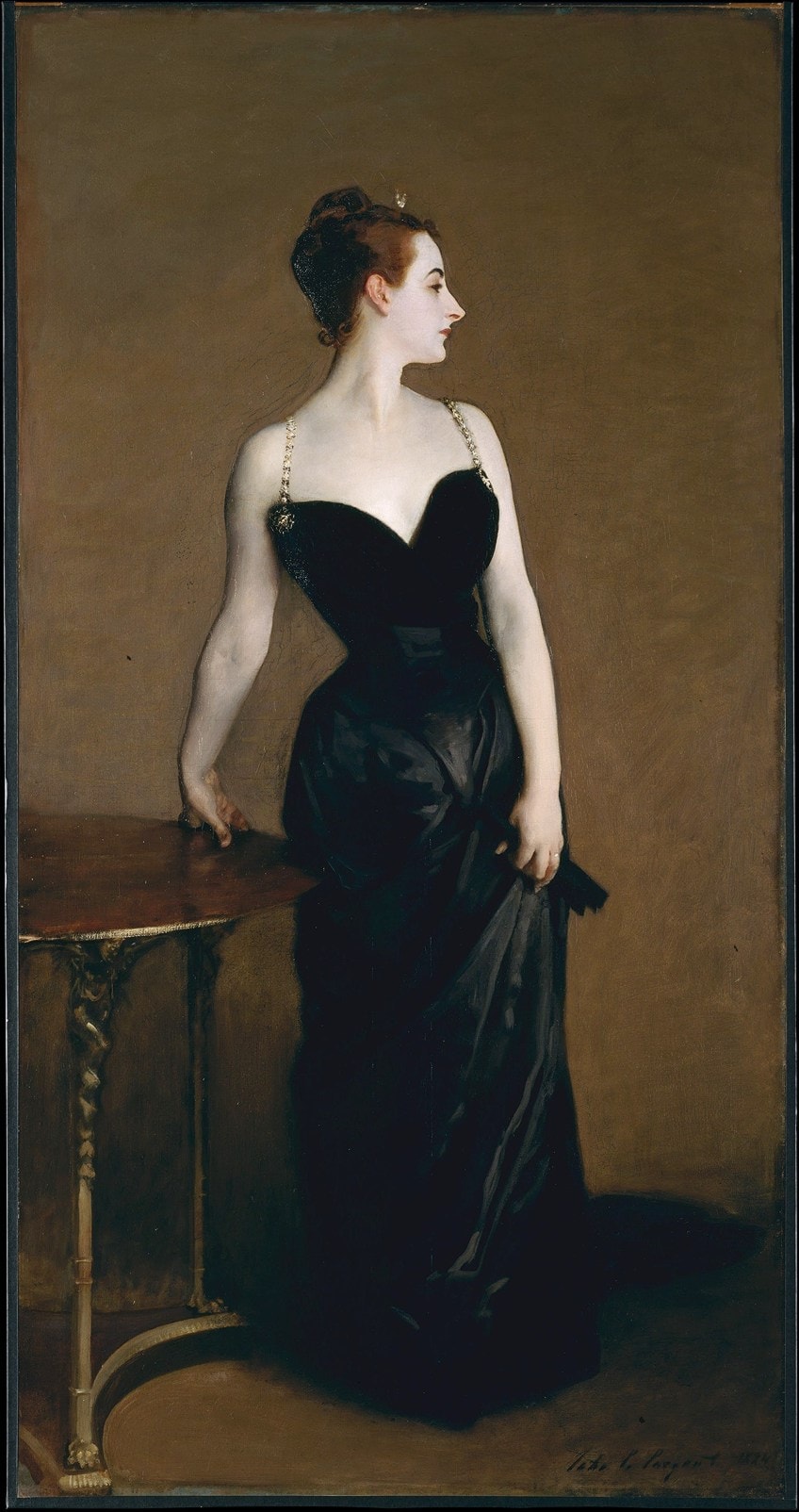

Portrait of Madame X (1883 – 1884) by John Singer Sargent

| Title | Portrait of Madame X |

| Artist | John Singer Sargent (1856 – 1925) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 235 x 110 |

| Date Created | 1883 – 1884 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

One of the most famous paintings at the met, John Singer Sargent’s painting of Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, a young socialite and the wife of French financier Pierre Gautreau, has infamously become known as Madame X or Portrait of Madame X. Madame X was painted at Sargent’s request rather than as a commission. It is an examination of conflict. A woman is depicted by Sargent posing in a black satin garment with jeweled straps, an outfit that both discloses and conceals. The portrait is distinguished by the subject’s pale skin tone in contrast to the background’s and dress’s dark hues.

Sargent experienced a brief setback in France as a result of the scandal surrounding the painting’s controversial reception at the Paris Salon in 1884, but it’s possible that it paved the way for his later success in Britain and America. The model was an American immigrant who settled in France and married a French banker. She rose to fame in Parisian high society for her beauty and her alleged extramarital affairs. She took great interest in her looks and wore lavender powder.

She was referred to as a “professional beauty,” an expression used in the English language to describe a lady who uses her individual talents to climb in society.

Artists were drawn to her because of her unusual beauty; according to American painter Edward Simmons, he “could not stop pursuing her as one does a deer.” Sargent was equally astounded and believed that a portrait of Gautreau would attract much interest at the approaching Paris Salon and spur demand for portrait commissions.

The response to the painting from the general population was so strong that Sargent left the country, and his high-society model’s reputation was permanently damaged.

One of the dress straps was initially seen hanging seductively from the subject of Sargent’s photograph, which now looks like an unimportant detail. The Parisian art scene was horrified not only by the subject’s exposing attire as well as by her eerie skin tone. Gautreau may have been consuming arsenic to lighten her complexion like other stylish women of her time (although Davis believes she more likely used rice powder) However, it’s unlikely that the lewdness of the image was what shocked Parisian society. Even worse, the artwork was considered to be tacky.

Self-Portrait with Straw Hat (1887) by Vincent Van Gogh

| Title | Self Portrait with Straw Hat |

| Artist | Vincent Van Gogh (1853 – 1890) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 41 x 32 |

| Date Created | 1887 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Vincent Willem van Gogh is one of the most well-known artists of his day. He was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who, after his death, rose to prominence and had a significant impact on Western art history. He produced around 2,100 pieces of art in a ten-year period, including about 860 oil paintings, the majority of which were produced in the final two years of his life.

These works, which range from landscapes to still lifes to portraits and self-portraits, are distinguished by their use of vibrant colors and dramatic, spontaneous, and expressive brushstrokes, which helped lay the groundwork for Modern art.

He did not have much commercial success, and at the age of 37, while suffering from acute melancholy and destitution, he took his own life. Self-Portrait with Straw Hat (1887) is part of a collection of self-portraits by Van Gogh, which consists of his own portraits and portraits of him painted by other artists.

A significant portion of Van Gogh’s body of work as a painter was made up of these numerous self-portraits. Van Gogh’s self-portraits most likely represent his face as it appeared in the mirror, which he used to reproduce his face, meaning that his right side in the picture is actually his left side in real life.

He once stated, “I purposely bought a good enough mirror to work from myself, for want of a model.”

Self-Portrait with Straw Hat demonstrates the artist’s knowledge of Neo-Impressionist techniques and color theory, which are aspects of his work that continue to be praised and studied today. This piece also gives clues to the artist’s deteriorating health. A man who is under emotional and physical strain is suggested by the three-quarter profile, dark shadows, and tight jaw. One blue and one green eye cast a haunting look that simultaneously begs for our assistance and pushes us away. As befits his self-image as a working man’s artist, Van Gogh is dressed in the yellow straw hat and work coat of a peasant laborer. This work is certainly a must-see at the Met.

The Water Lily Pond (1899) by Claude Monet

| Title | The Water Lily Pond |

| Artist | Claude Monet (1840 – 1926) |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 92.7 x 73.7 |

| Date Created | 1899 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

The Water Lily Pond (1899), also known as Japanese Bridge, is one 250 oil paintings by Impressionist artist Claude Monet depicting the artist’s flower garden at this Giverny home, expressing an artistic curation of flora in the Impressionist style.

Monet only painted three works depicting his water lily pond.

The Water Lily Pond is stunning in its arrangement of the bridge, weeping willow, and background trees, all of which underwent numerous changes up to 1910. The pond is full of plants and water lilies, creating a rich scene of color. The work is made up of brief brushstrokes, which Monet frequently used as he became older.

In a letter, Monet explained that he had planted the water lilies only for amusement; he had never intended to paint them, but as soon as they took root, they nearly served as his sole source of inspiration. He wrote; “I saw, all of a sudden, that my pond had become enchanted… Since then, I have had no other model.”

Many reviewers noted Monet’s debt to Japanese art when he displayed these paintings at Durand-Ruel’s Gallery in 1890.

The National Gallery painting’s impenetrable green enclosure, which is made more telling by the placement of the bridge’s top arch just below the top edge, is reminiscent of the Hortus conclusus (closed garden) of Medieval works while also conjuring up a dreamlike contemplative space that is consistent with symbolist literature, particularly poems like Stéphane Mallarmé’s Le Nénuphar blanc.

This result was noted by Gustave Geffroy in his evaluation of the exhibition, describing the work as “[a] minuscule pool where some mysterious corollas blossom” and “a calm pool, immobile, rigid, and deep like a mirror, upon which white water lilies blossom forth, a pool surrounded by soft and hanging greenery which reflects itself in it.”

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950) by Jackson Pollock

| Title | Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) |

| Artist | Jackson Pollock (1912 – 1956) |

| Medium | Enamel paint on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 266.7 x 525.8 |

| Date Created | 1950 |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950), by American artist Jackson Pollock, is a 1950 abstract expressionist painting in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pollock was a key player in the Abstract Expressionist art movement, gaining notoriety for his “drip technique”, which he employed to paint his canvases from all sides by sprinkling or pouring liquid home paint over a horizontal surface.

Since he covered the full canvas and painted with his entire body, frequently in a frantic dance way, it was also known as all-over painting and action painting.

The critics of this extreme kind of abstraction were divided: some lauded the spontaneity of the production, while others mocked the random results. Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) is a distinguished example of Pollock’s signature poured-painting style and is often considered one of his most notable works.

Autumn Rhythm was one of a collection of paintings Pollock originally displayed at the Betty Parsons Gallery in November and December 1951, and was created in the fall of 1950 at Pollock’s studio in Springs, New York. Like previous paintings he created during this period of his career, Pollock’s technique involved pouring paint from cans or utilizing sticks, heavily laden brushes, and other tools to control a stream of paint as he dripped and tossed it onto the canvas. One of Pollock’s largest works is Autumn Rhythm, which is 17 feet wide by 8 feet high.

Despite its innovative method, Pollock’s large-scale work was influenced by the muralism of the 1930s, particularly the work of David Alfaro Siqueiros and Thomas Hart Benton, both of whom he had collaborated with. This enormous Pollock painting was purchased by the Met Museum in 1957, the year after the artist’s untimely passing, demonstrating how fast his innovation of painting was embraced by the modern art scene.

The Metropolitan Museum of Art is certainly home to a wide collection of artworks, and it can be difficult for visitors to figure out which works are must-sees. This list provides a list of Met Museum highlights of some of the museum’s greatest paintings, as well as their histories and backstories to provide a greater understanding and richer viewing experience.

Take a look at our paintings at the Met webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Which Paintings Are a Must-See at The Met?

The Metropolitan Museum of Art houses a wide and diverse collection of artworks. When it comes to the collection of paintings, some must-sees include Madonna and Child Enthroned with Saints (1504) by Raphael, Venus and the Lute Player (1565-1570) by Titian, Aristotle with a Bust of Homer (1653) by Rembrandt, The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) by Emmanuel Leutze, The Dance Class (1874) by Edgar Degas, Portrait of Madam X (1883-1884) by John Singer Sargent, Self-Portrait with Straw Hat (1887) by Vincent Van Gogh, Water Lily Pond (1899) by Claude Monet, and Autumn Rhythm (Number 30) (1950) by Jackson Pollock.

What Are Examples of Metropolitan Museum of Art Artworks?

Some of the most famous artworks at the Met include The Harvesters (1565) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, View of Toledo (date unknown) by El Greco, Young Women with a Water Pitcher (1662) by Johannes Vermeer, Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zúñiga (1787-88) by Goya, Boating (1874) by Édouard Manet, and Dutch Interior (III) (1928) by Joan Miró.

What Famous Pieces of Art Are at The Met?

You may be wondering what famous pieces of art are The Met, although to answer this question would require an entire article of its own. However, some of the most famous pieces of art at the Met include The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851) by Emmanuel Leutze, Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1545) by Benvenuto Cellini, Venus Italica (1802) by Antonio Canova, and Ugolino and his sons (1865-1867) by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Famous Paintings at The Met – The Best Met Museum Highlights.” Art in Context. September 1, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/famous-paintings-at-the-met/

Meyer, I. (2022, 1 September). Famous Paintings at The Met – The Best Met Museum Highlights. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/famous-paintings-at-the-met/

Meyer, Isabella. “Famous Paintings at The Met – The Best Met Museum Highlights.” Art in Context, September 1, 2022. https://artincontext.org/famous-paintings-at-the-met/.