Native American Art – A History and Overview of American Indian Art

Native American art refers to the artwork created by the original native people of the Americas. Despite not having any connection to India, the aboriginal people of the region are often referred to as Indians, and their art is known to many as American Indian artwork. Native art from the Americas includes Native American sculpture, textiles, basket weaving, Native American paintings, murals, and Native American drawings from North and South America, as well as parts of Siberia, Alaska, and Greenland.

Native American Art

“Art” is a term that can mean various things, depending on where you come from. In many of the languages spoken by Native Americans, there is not even a word for artist or art. So how would we define Native American artists?

The Role of the Native American Artists

Most of native life revolves around the perfection of various crafts for practical reasons such as pottery for food storage, clothing for everyday and ritualistic uses, baskets for transporting and storing goods, and so on. In these native societies, an artist was simply someone who was good at their craft or job.

Instead of making art for aesthetic appreciation, the craftsman aspired to create effective and practical objects for daily use and powerful objects for medicinal or spiritual use.

It was only in cultures where wealth was a significant factor in one’s social status that artists were seen as anything important. The ruling class of some of these native cultures was often in clerical positions that required them to commission the creation of religious and memorial art from Native American artists. Although art itself was not seen as something worth pursuing in many native cultures, the skill of being able to craft fine baskets or spiritual motifs was still admired and appreciated by others.

Individual Art vs. Tribal Art

Every artist’s primary goal is to evoke an emotional response from their viewers. This is no different for American Indian artists. Success in communicating with Native American civilizations depended a lot on the artist’s understanding of traditions.

The social structure of various tribes limited the amount of experimentation an artist could do compared to Western civilizations, forcing the artist to stick to more traditional forms of expression.

Nonetheless, there was a remarkable amount of artistic freedom inside this strict framework of tradition. There are documented examples of people making significant changes in their tribes’ art and economics. Through pure individuality, these people accomplished a personal victory by establishing a style that was not only replicated by other craftsmen but was also recognized as “traditional” in that specific region over time.

American Indian Artwork Design Origins

The origins of most Native American ornamental patterns are unknown today; the majority of them were lost in prehistory. Many are clearly inspired by natural shapes, but some are simply extensions of geometric themes. A few have gotten so entwined with foreign constructs such as Western art following the arrival of the Europeans, that it is hard to trace their origins fully. However, there is evidence that certain early patterns were developed by individual artists, and many of them were motivated by a quest for significance.

To American Indians, the world of the vision quest is a spiritually significant space where the soul may leave the body, participate in strange activities, and see many unusual things.

The designs and creatures experienced during the vision quest are often seen as protective beings, and so are painstakingly reproduced throughout the day to reflect this belief. Non-artists would periodically tell a chosen artist about their imaginary animals, and the artist would subsequently record them on stone, wood, or hide. However, because these paranormal encounters were so intimate, they were frequently chronicled by the subject themselves, resulting in work of widely varying quality.

The Cultural Function of Native Art

Many American Indian art items are primarily designed to serve a function, such as acting as a vessel or providing a method of devotion. Native American artworks frequently assume practical forms that reflect the social organization of the civilizations involved. Munitions, jewelry, and pageantry appear to have been significant art forms in geopolitical civilizations. Plains, Incan, and Aztec civilizations all reflect the prevailing warrior culture in their arts, making them the most pronounced examples.

Civilizations that place a high value on ritual have more ceremonial art than cultures that do not. For example, all of the Mayans’ artistic manifestations show the world’s overwhelming theocratic state.

Some of the greatest American Indian artwork was applied to items meant to satisfy a divinity, calm furious deities, appease or terrify malevolent spirits, or pay homage to the freshly born or lately departed, although this is not always true. Native Americans used such methods to exert control over their surroundings and any humans or mythological beings that endangered them.

Some articles were only meant for religious use, while others were only meant for secular use. The way things are decorated doesn’t necessarily give away what they’re used for. Some of the most revered religious artifacts are bare-bones, even unattractive, while others are opulently adorned.

Some folks used plainware bowls for meal preparation while others preferred polychrome bowls. Many objects had a dual function: they could be used for everyday domestic chores, but under specific circumstances, they might also have a religious purpose. The American Indian artist’s objective was to create semi-magical designs, which are common in non-Western cultures’ art, rather than just accurate records.

The artist quickly realized that he or she could not construct a flower as perfectly as the Maker could, so the artist chose not to try. Instead, he or she sought for the spirit or soul of the flower and represented it in the artwork in question.

Materials Used in American Indian Artwork

The diverse Native American tribes created art that represented their surroundings by working with materials indigenous to their own homelands. Those who lived in densely wooded areas, for example, necessarily became great wood sculptors; those who had access to clay became skilled sculptors, and those who lived in grasslands were skilled wicker makers.

American Indian artists had investigated and perfected nearly every natural medium such as rare stones, shells, metal, fiber from Milkweed, and birch bark.

Materials from animals were used such as hair from deer, llama’s droppings, quills from porcupines, and even sea lion whiskers were all utilized by the artist to add colors or textures to the completed work. When such materials became commodities in themselves, they were exchanged across long distances; for some things were not considered “official” unless they were made of a designated substance, and, especially for religious purposes, a replacement couldn’t be accepted.

The materials often reached a standardized value in the economy and were readily accepted as a unit of trade wherever they were popular.

The Various Types of Native American Artworks

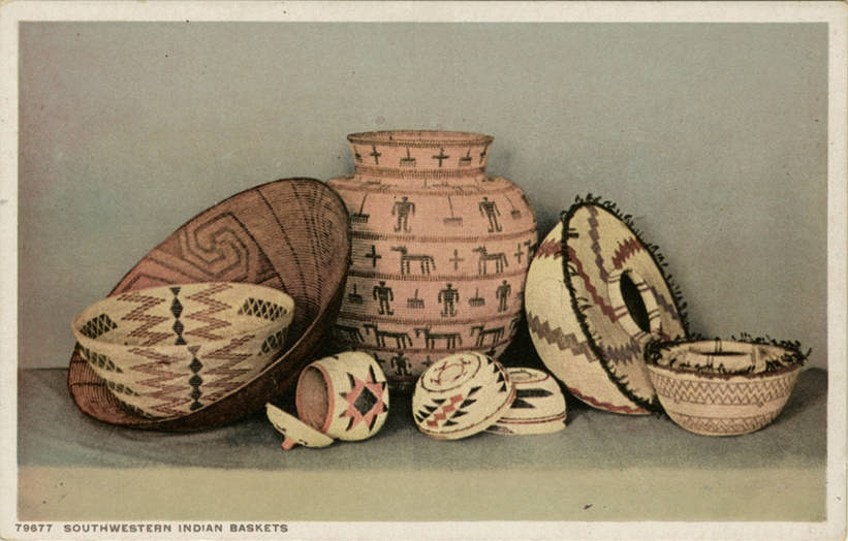

There were many different objects created by Native Americans that can be appreciated for their artistic craftsmanship and aesthetic beauty. Native art includes baskets, beadwork, quillwork, ceramics, and sculpture. Each one of these took great skill and differed from region to region.

Basketry

Shape, method, resources, and ornamental features all vary widely among baskets made by different ethnic groups or locations. Weavers choose individual components on a blend of tribal custom and individual preference, as well as the hue, texture, and appropriateness of the materials for the basket’s intended function. Textiles employ many of the same methods as basket weaving, while ceramics copy some of the same container shapes and external decorations.

Beadwork and Quillwork

Porcupine quills were originally utilized by Plains and East Coast cultures to adorn a broad range of things, including clothes and basket weaving. This labor-heavy type of ornamentation persisted until the mid-1800s when commerce with Europeans made glass beads more readily available. With this new media, painters could create patterns with greater complexity and a larger variety of colors. The chosen colors and themes show regional preferences as well.

Ceramics

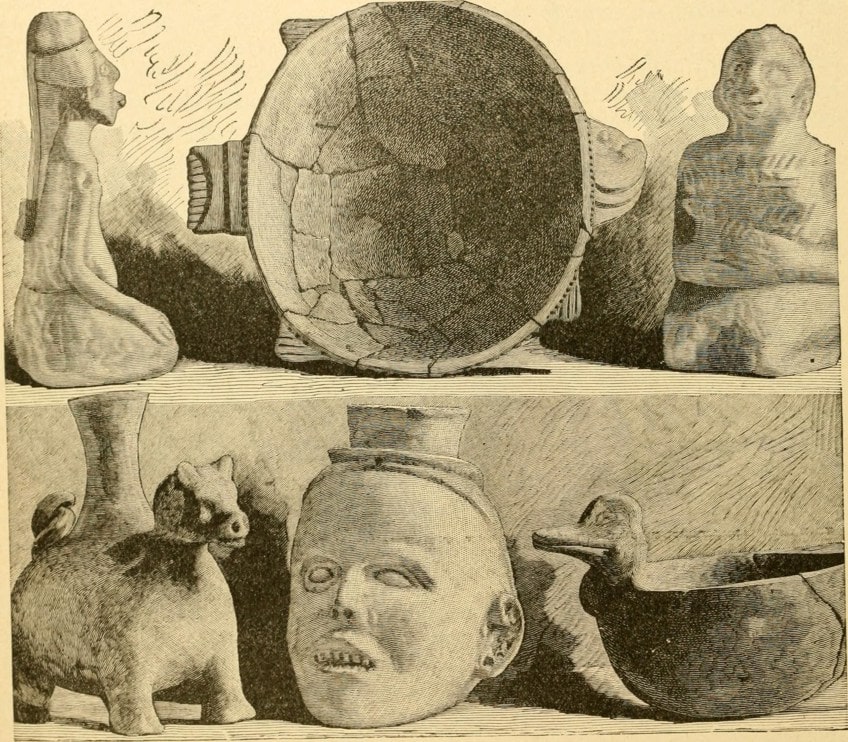

Religion, architecture and the arts have a combined three-thousand-year history in the Southwestern United States and Mexico. The Acoma, Zuni, and Hopi peoples, including the Rio Grande Pueblos, are all descended from the Ancient Pueblo people of New Mexico and Arizona, and some of these towns have been inhabited for centuries. The pottery we see now is the result of a tradition that dates back over a thousand years.

Native American Sculpture

Aboriginal artists use a wide range of materials, such as stones, bones, and wood, depending on what’s readily available. When it comes to the subject matter, sculptors frequently represent the things they are most familiar with: local flora and wildlife, humans, and mythological figures. A love of materials and a regional aesthetic have been passed down through generations of sculptors since the first people of North America began making art.

The Various Regions of American Indian Artwork

Native Art can be found all across the Americas. This includes places such as the Arctic, as well as Northern and Southern America. Each region has its own local style and variation of traditional Native American art.

Arctic

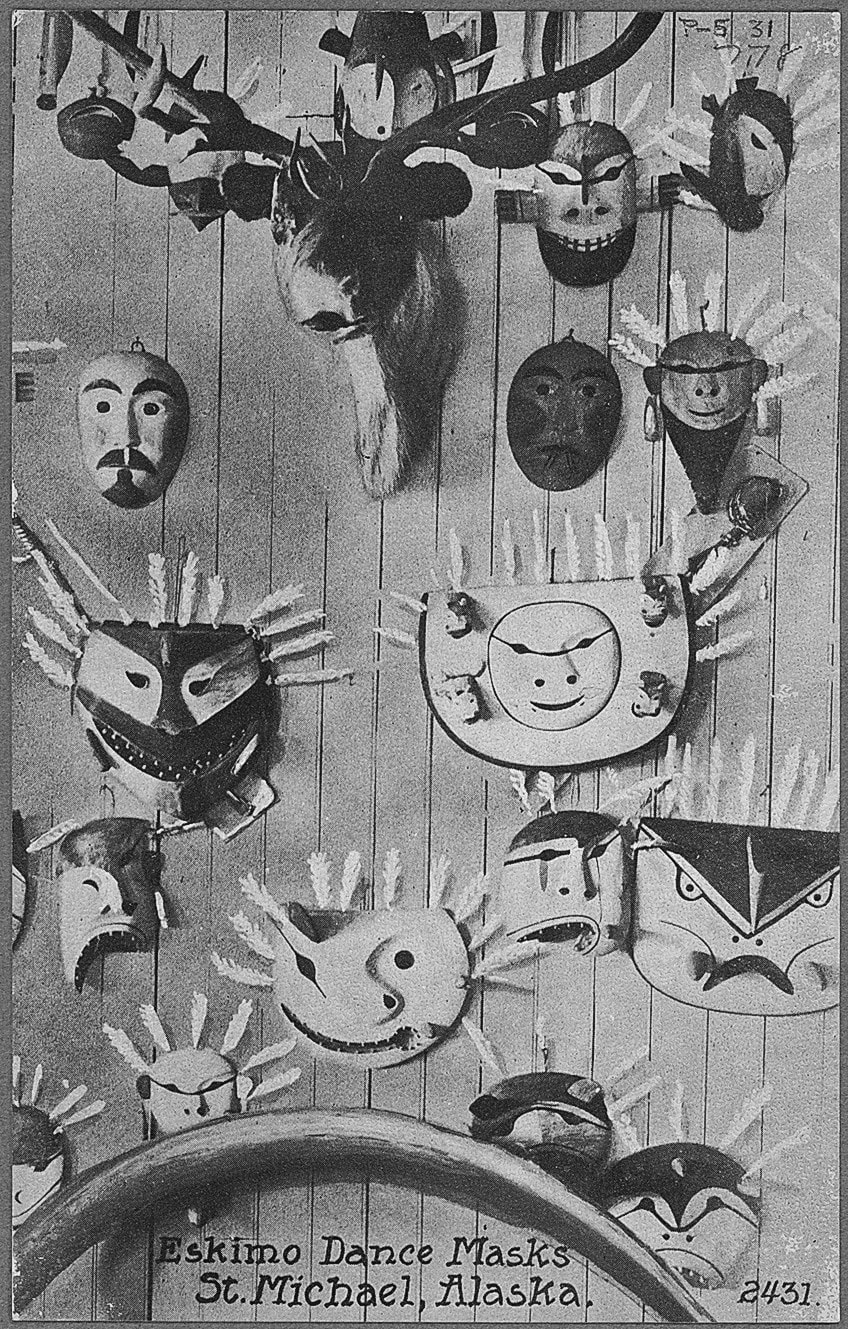

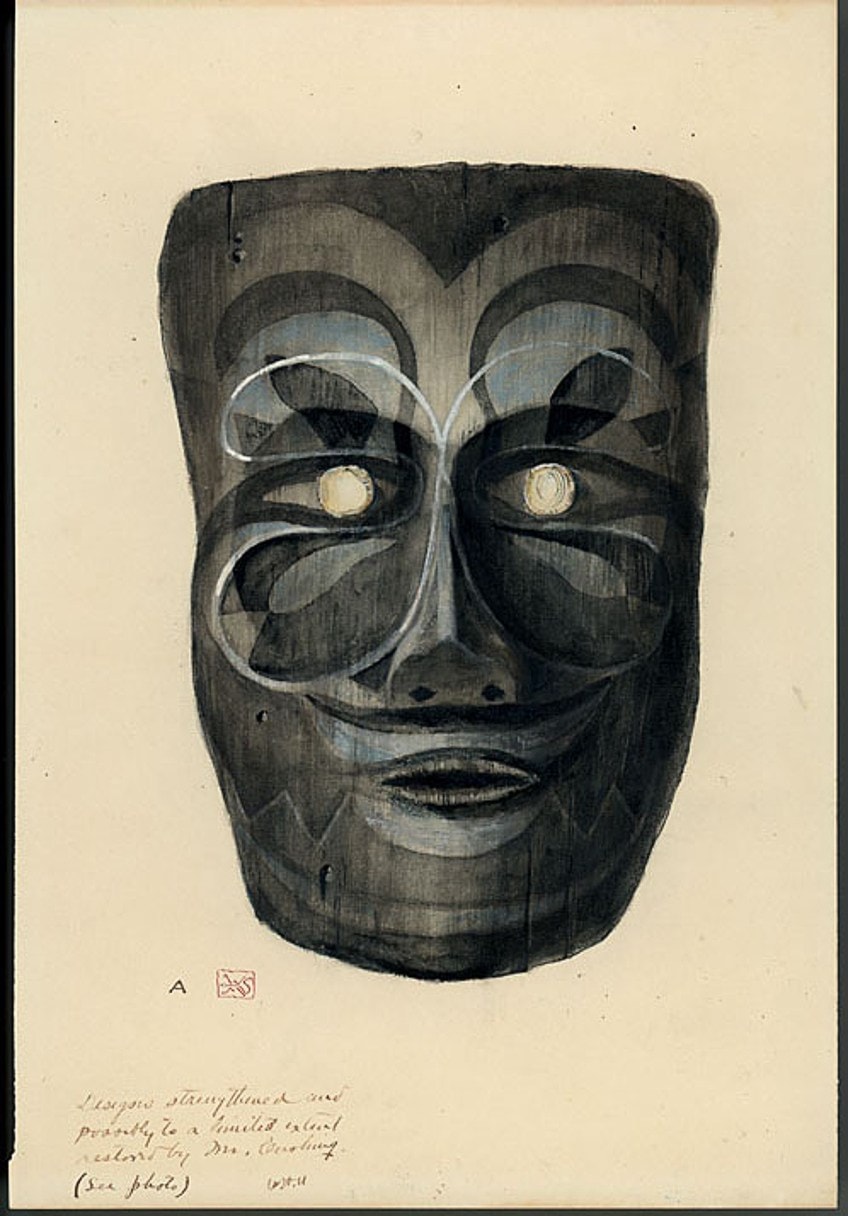

Alaska’s Yup’ik people have a long history of creating shamanic ceremonial masks. Since the Dorset civilization, indigenous peoples in the Arctic have created artifacts that could be considered works of art. Dorset walrus ivory sculptures were mainly spiritual, but the Thule people’s art, which supplanted them about the year 1000 CE, was more ornamental. The historical period of Inuit art began with the arrival of Europeans. The modern era of Inuit art began in the late 1940s when the Canadian government encouraged the artists to make prints and serpentine carvings for distribution in the south.

Northeastern Woodlands

East of the Mississippi River in North America, the Eastern Woods, or simply woodlands, cultures have existed from at least 2500 BCE. It’s important to note that while there were several culturally diverse groups living in the area, commerce between them was widespread, and they all practiced earth mound burial, which has conserved a significant amount of their artwork.

For this reason, these people are referred to as Mound Builders.

Early, medium, and late Woodland civilizations subsisted primarily on foraging throughout the 1000 BCE to 1000 CE era. The Deptford culture’s ceramics (c. 2500 BCE–100 CE) provide the oldest evidence of an artistic tradition in the area. Another well-known early Woodland civilization is that of the Adena people. They etched anthropomorphized animal patterns on stone tablets, made ceramics, and made ceremonial garments out of animal skins and antlers. Shellfish was a staple of their diet, as shown by the discovery of carved shells in burial mounds.

Southeastern Woodlands

Florida has turned up a slew of pre-Columbian wooden items. While the earliest wooden artifacts date back as far as 10,000 years, carved and painted wooden artifacts date back no further than 2,000 years. Several Florida locations have animal effigies and masks on display. On the western shore of Lake Okeechobee, a funerary pond had animal effigies dated from 200 to 600 A.D. A 66-centimeter-tall sculpture of an eagle is particularly striking.

In 1896, in Key Marco in southern Florida, more than 1,000 sculpted and decorated wooden artifacts, including masks, inscriptions, tablets, and statues, were unearthed.

They have been characterized as some of North America’s greatest prehistoric Native American paintings. The items are not precisely dated, although they may date from the first millennium of the present period. Similar statues and figurines were mentioned by Spanish missionaries as being used by the Calusa late in the 17th century, as well as at the old Tequesta site on the Miami River in 1743, however, no specimens of the Calusa artifacts from the historic era have survived.

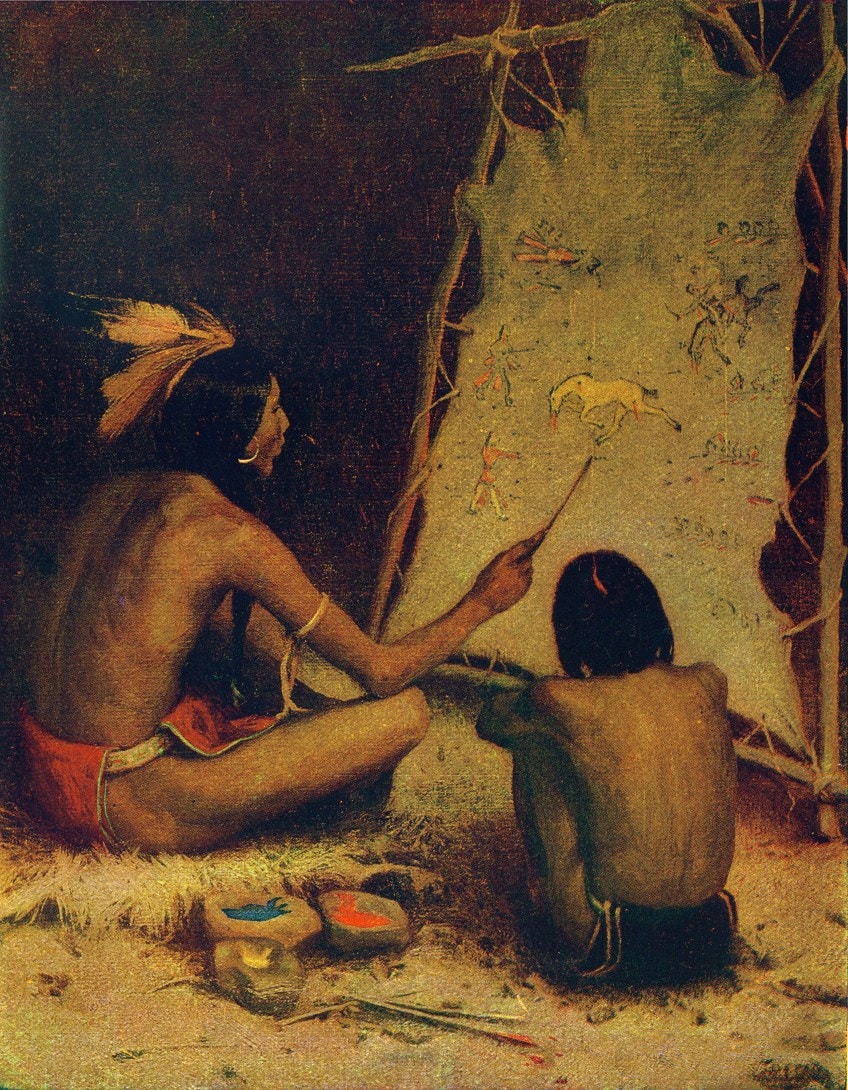

The Great Plains

The introduction of the horse transformed the civilizations of several ancient Plains tribes. Equine culture allowed tribes to live entirely mobile lives, chasing buffalo. Buffalo hide was embellished with porcupine quill needlework and beads, teeth of elk, and dentalium shells, which were highly valued resources. Glass beads and coins obtained through commerce were later integrated into Plains art. Plains beading has thrived into the modern day.

Buffalo hide was the most commonly used material for painting.

Men produced narrative, graphic designs that documented their experiences or dreams. They also painted Winter counts, which are graphical periodic calendars. Women drew geometric patterns on skinned robes, which were occasionally used as maps. Buffalo herds were deliberately exterminated by European hunters during the Reservation Era of the late 19th century. Due to the shortage of skins, Plains painters experimented with alternative painting media such as paper or muslin, giving rise to Ledger art, dubbed after the omnipresent ledger papers used by Plain’s painters.

Plateau and Great Basin

The Plateau area and upper Great Basin have been a trading hub since the archaic period. People from the Plateau have typically resided near major river systems. As a result, their work is influenced by other areas, such as the Pacific Northwest coastlines and the Great Plains. Women from the Nez Perce, Yakama, Umatilla, and Cayuse tribes make flat, square corn husk or hemp dogbane bags embellished with bright, geometric patterns in faux stitching.

Plateau bead workers are noted for their intricate equine ornamentation and contour-style beading.

California

Native Americans in California have a rich heritage of intricate basket weaving techniques. Baskets made by artisans from the Chumash, Miwok, Hupa, Pomo, Cahuilla, and other tribes were popular with dealers, museums, and travelers in the late 19th century. This led to a significant deal of ingenuity in the shape of baskets.

Many works by Native American basket weavers from California’s various regions are currently housed in museum collections.

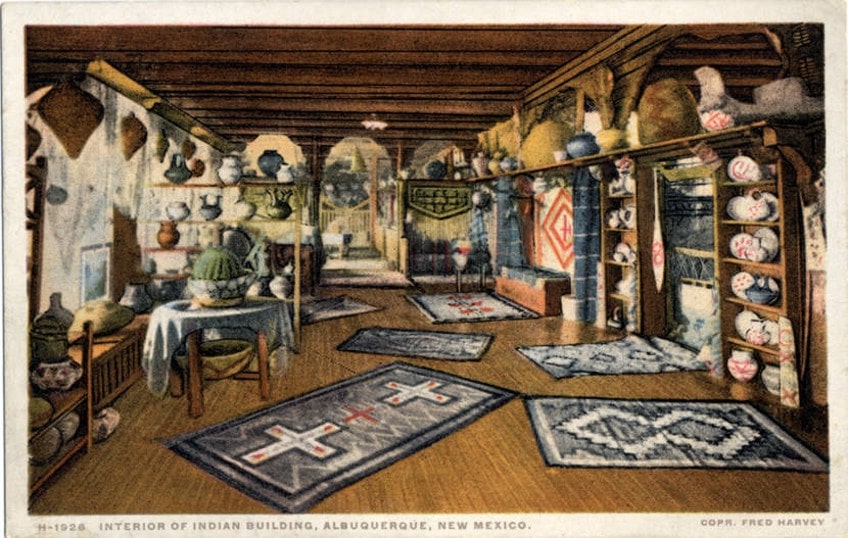

Southwest

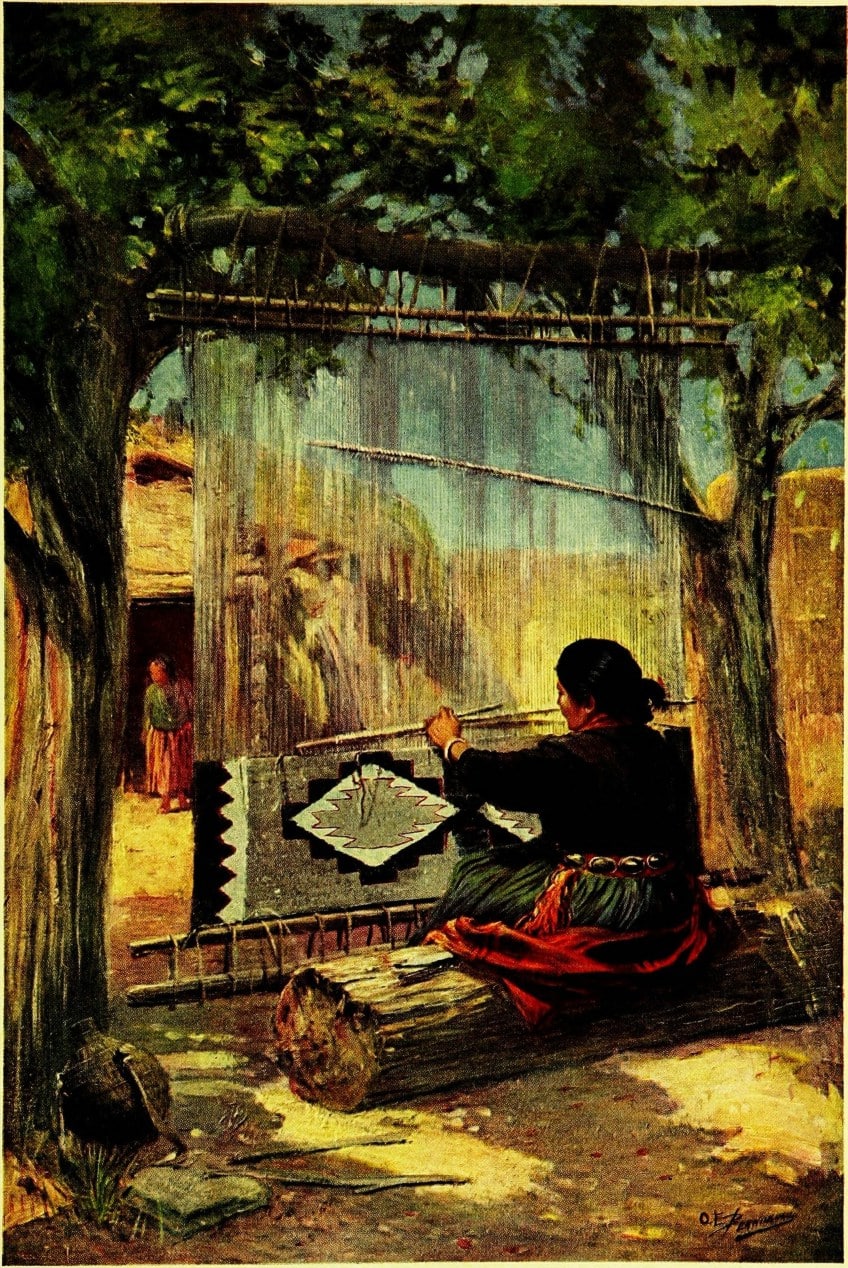

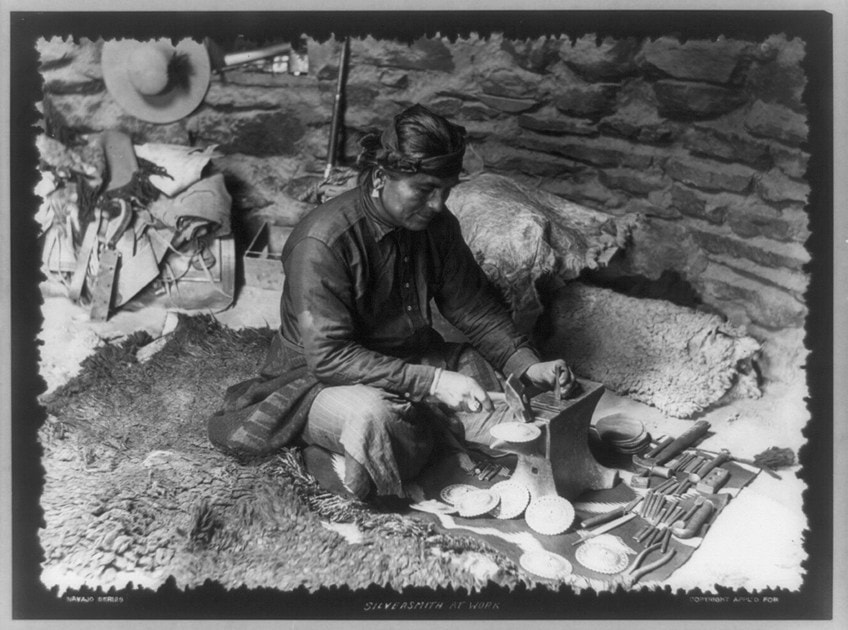

Athabaskan peoples moved from northern Canada to the southwest throughout the last millennium. Among them are the Navajo and Apache. Sandpainting is a technique used in Navajo healing ceremonies that have spawned an art form. Navajos learned to weave on upright looms from Pueblos and made blankets that the Great Basin and Plains tribes avidly gathered in the 18th and 19th centuries.

After the railroad was built in the 1880s, imported blankets became plentiful and cheap, thus Navajo weavers began creating carpets for commerce.

Navajos learned silversmithing from Mexicans in the 1850s. The first Navajo silversmith was Atsidi Sani, but he had numerous pupils, and the technology rapidly spread to neighboring villages. Thousands of artisans now create silver jewelry with turquoise. Hopi are well-known for their cottonwood carving and overlay silver work. Zuni artisans are well-known for their cluster work jewelry, which features turquoise patterns, as well as their intricate, pictorial stone inlay in silver.

Mesoamerica

The Olmec, who resided on the gulf coast, was Mesoamerica’s first completely developed civilization. Their civilization was the first to establish many characteristics that remained constant throughout Mesoamerica until the Aztecs’ final days, such as a sophisticated astrological calendar, and the building of stelae to commemorate significant events.

The most renowned artistic achievements of the Olmec are enormous basalt heads, which are thought to be portraits of kings constructed to demonstrate their tremendous authority.

The Olmec also carved votive figures, which they buried beneath their home floors for unexplained purposes. Teotihuacan, a city in Mexico’s Valley, has some of the biggest pre-Columbian pyramidal constructions. The city was founded approximately 200 BCE and flourished during the 7th and 8th centuries CE. Several of the paintings at Teotihuacan, Mexico, have survived quite well.

Notable American Indian Artists

The art of Native Americans covers a large span of time. Most of the names have been forgotten, but there are a few that have left their legacy. It is important to pay due respect to the pioneers of their times.

Nampeyo (1859 – 1942)

| Place of Birth | Hano Pueblo, Arizona |

| Date of Birth | 1859 |

| Popular For | Ceramics |

| Associated Movement | Sikyátki Revival |

Nampeyo was born in Tewa Village, which is largely made up of relatives of the Tewa people of New Mexico who migrated west to the Hopi territory around 1702 for refuge from the Spanish following the 1680 Pueblo Revolt. Her mother, White Corn, was Tewa, while her father, Quootsva, was a Snake clan member from neighboring Walpi.

Known as one of the best Hopi potters at the age of 20, Nampeyo mastered the skills she inherited from her grandmother utilizing recycled potsherds as a base material.

Few potters have been able to achieve the same level of style, accuracy, and long-lasting beauty as her. Nampeyo is well-renowned for its polychrome patterns, which employ a technique known as chewed yucca leaf painting to apply brilliant hues including red, brown, yellow, and deep black.

When it came to her ceramics, she used geometric forms coupled with images of animals and people to create a very detailed and natural theme that was then immortalized using a firing method that goes back to the 1400s. Nampeyo polished the burned pots with a shrub with a red bloom and put sheep bones in the fire to make it hotter or make the pottery whiter. Both methods date back to Tewa pottery’s early history.

Lucy M. Lewis (1890 – 1992)

| Place of Birth | Acoma Pueblo, New Mexico |

| Date of Birth | 1890 |

| Popular For | Ceramics |

| Associated Movement | Native American Sculpture and Ceramics |

Lucy M. Lewis was a ceramicist from Acoma Pueblo, most well-known for her decorated pottery that was painted in black and white using techniques passed down through Native traditions. Lewis started producing pottery when she was eight years old, after learning with her great aunt, Helice Vallo. Her parents also worked in Grants, a nearby town, on occasion. Her first attempts at ceramics were aimed at visitors. The ash-bowls were simple to make and sold for five or ten cents each.

Lewis married Toribio “Haskaya” Luis in the late 1910s. When the oldest son, Ivan, joined the Marines during WWII, the familial title was changed to Lewis. She had nine children, seven of whom became potters. Her use of tiny lines demonstrates a particular blend of skill, accuracy, and symmetry. Lewis had little official schooling and was primarily self-taught, despite her competence and creative talent. She was welcomed to the White House in 1977, and her work is housed in the Smithsonian Museum in Washington, D.C.

Lewis won numerous prestigious accolades during her life and career, including the New Mexico Governor’s Award for exceptional personal achievement and recognition from the American Crafts Council College Art Association.

Kananginak Pootoogook (1935 – 2010)

| Place of Birth | Cape Dorset, Canada |

| Date of Birth | 1st January 1935 |

| Popular For | Sculpting and Printmaking |

| Associated Movement | Inuit Art |

Kananginak Pootoogook was a guy who lived amid the elements. Despite being a twentieth-century ink sculpture and printer, he spent most of his childhood moving from igloos in the winter to sod houses in the summer. His work, as a self-taught artist, frequently acknowledges the shift from traditional Native American living to a modern lifestyle. Pootoogook’s art also demonstrates a strong sense of unity and respect for the relationship between man and the environment. His works depict animals imitating human characteristics and vice versa, demonstrating the equality of coexistence between man and beast.

Among many other awards, an exhibition of his art was included during the 2010 Winter Olympics in Vancouver.

While working on his final, incomplete sketch of his father’s Peterhead boat, he was stricken with coughing fits, which he identified as cancer. He went to Ottawa with his wife, Shooyoo, and was diagnosed with lung cancer while residing at the Larga Baffin residence. He had surgery in October 2010 and did not recover. He passed away on November 23, 2010, in Ottawa. His wife, seven children, and several grandchildren and great-grandchildren survive him. He was laid to rest in Cape Dorset.

Ernie Pepion (1943 – 2005)

| Place of Birth | Browning, MT |

| Date of Birth | 11 May 1943 |

| Popular For | Native American Drawings and Paintings |

| Associated Movement | Native American Art |

Ernie Pepion grew up in Browning as a rancher and rodeo performer. He fought in Vietnam and was in a vehicle accident after returning that left him mostly disabled. He was still able to talk and use one of his hands, but he would never be capable of walking again. While at a rehabilitation center in Long Beach, California, he began painting. His teacher was another veteran with an iron lung who could only live for one hour a day without the use of equipment. During that period, he painted, and Pepion learned to utilize painting to fill the hours.

Painting ultimately became Pepion’s personal form of healing therapy.

Pepion returned to Montana and enrolled in studies at Montana State University, where he earned a master’s degree in art. He went on to become a renowned painter from there. Pepion’s art is shockingly personal, relying on his own experiences as a Blackfeet Indian and a paraplegic.

His works, frequently on the same canvas, show both comedy and anguish, striking the spectator like a metal hand in a velvet glove. Many of his works are motivated by honesty. He died of natural causes at the age of 61. His art, however, continues on and was shown in a special memorial exhibition at the Emerson Cultural Center. The presentation began with a few friends reflecting on his work and has evolved to a month-long event.

Contemporary Native American Artists

Despite having ancient roots, American Indian artwork still thrives today. Native art has moved from primarily tribal in function, to representing something that is both individual, yet respectful of its traditions and heritage. Let us look at a few of the contemporary creators of Native American paintings, Native American drawings, and other mediums, as they help to redefine what it means to be one of the modern Native American artists.

Modern Native American Art

It’s difficult to pin down exactly when “modern” and current Native art first emerged. Western art historians have previously seen the use of Western art mediums or participation in international art exhibitions as criteria for contemporary Native American art.

The study of Native art history is a relatively young and hotly debated academic field, and the Western cultural standards that were formerly widely accepted are no longer.

Native artists have used a wide range of mediums, including stone and wood sculpture and mural painting, that are now regarded as acceptable for easel art. The idea that great art can’t serve a practical purpose isn’t widely accepted in the Native American art world, as demonstrated by the high regard and importance accorded to blankets, baskets, weapons, and other practical artifacts in Native American art exhibitions. Contemporary Native art seldom has a fine art versus craft divide to speak of.

George Longfish (1942 – Present)

| Lived In | Oshweken, Ontario |

| Tribe | Seneca and Tuscarora |

| Medium | Assemblage, painting |

George Longfish was born in Ohsweken, Ontario, on the 22nd of August, 1942. At the age of five, his mother took him and his brother to the Thomas Indian school and left them there. There they were responsible for looking after the animals of the farm, as well as slaughtering them. Through the paintings that he created as a child, he portrayed life without his mother and how removed he felt from his culture.

Throughout his nine-year stay at the school, he felt his connection with his Native American heritage disappear.

He mostly produced art in modernist and socially conscious styles. His work has been recognized as being a catalyst for the rise of contemporary Native artists as well as the Native art movement as a whole. In his books, he examines the ways in which we define our own identities, probing their historical, social, political, and psychological roots.

He believes that the more control they have over our spiritual, moral, and survival information, as well as our language, the less power they have over them.

One thing he feels we can learn from history is how to use spiritual and warrior knowledge from the past in the present. Many of his pieces have been shown in important public museum exhibitions, such as the Heard Museum. His Native American paintings incorporate elements of native motifs with Pop art, and frequently make use of Assemblage.

Will Wilson (1969 – Present)

| Lived In | San Francisco |

| Tribe | Navaho |

| Medium | Photography |

Will Wilson was born in the city of San Francisco, yet most of his youth was spent growing up on the Najaho Nation reserve. After receiving a scholarship, he was moved from the reserve to a school in Massachusetts. He received a Bachelor of Arts in studio art from Oberlin College and a Master of Fine Arts in photography from the University of New Mexico.

The Critical Indigenous Photographic Exchange, one of his most well-known initiatives, challenges and develops on the depiction of Native indigenous peoples established by photographer Edward Curtis. Curtis’ photos, according to Wilson, are part of what keeps Native people frozen in time.

With his photographs, Wilson intends to continue Curtis’ documentary work from the perspective of an aboriginal, cultural practitioner in the 21st century.

Wilson wants to replace Curtis’ Colonial gaze and the impressive amount of anthropological material that Curtis gathered with a modern perception of Native North America. It was his belief that these things, rather than the old mindset of integration, are the only things that may help them to reinvent who they really are as Indigenous Americans.

Frank Buffalo Hyde (1974 – Present)

| Lived In | New York |

| Tribe | Onondaga |

| Medium | Multi-media Paintings |

Frank Buffalo Hyde, an Onondaga artist, was born in New York in 1974 and raised on his mother’s Onondaga reserve. At the age of 18, he began displaying his work as a pastime. After he graduated from the Institute of American Indian Arts, he began to take his painting profession more seriously. His work has been described as funny, with bright colors and odd topics such as hamburgers and buffaloes, such as seen in his piece Buffalo Fields Forever (2012).

In order to create his artwork, he incorporates elements of internet culture and modern technology, as well as traditional Native American concepts.

Hyde intends for his work to serve as a commentary on current societal and political issues. In addition, he is motivated to continue his art by highlighting indigenous concerns. His ultimate objective with his work is to dispel any preconceived notions about Native American art and the individuals who create it.

He believes that aspiring Native American artists may produce any art they want without worrying about whether or not it’s authentically Native American.

Hyde’s Native American paintings combine elements of graffiti art, graphic arts, stunning color, and humorous surrealism. His viewpoint on his experience as a Native American or a Native artist, on the other hand, is not at all humorous or whimsical.

Merrit Johnson (1977 – Present)

| Lived In | Baltimore, Maryland |

| Tribe | Mohawk and Blackfoot |

| Medium | Traditional Materials |

Born in Baltimore, Maryland in 1977, this Blackfoot and Mohawk native artist works with a multitude of traditional materials and disciplines. Her work seems familiar and different at the same time, as well as approachable and challenging. Her art is filled with nuances, references, and difficulties that pull the spectator into broader, deeper dialogues about cultural concealment and security, communities, and people’s relationship with the earth.

The evidence for this can be found in her art, which frequently incorporates organic and natural materials like shells and furs, as well as well-known iconography, but does so in an unconventional manner.

She uses her art to convey a complex message about the long and complicated history of the United States and Native Americans. Until recently the native people were not even part of the American conversation.

Her art delves into questions about cultural camouflage, how natives view themselves, their necessity for protection, and how they are viewed and threatened by other people. It explores how animals of all kinds have a fear of being prey, and how humans are also animals.

Being both a descendant of Native Americans and settlers, she feels that her work offers her an opportunity to discover her roots, as well as understand the dualities that exist both within her work and herself.

Nicholas Galanin (1979 – Present)

| Lived In | Sitka, Alaska |

| Tribe | Tlingit and Unangax̂ |

| Medium | Art, Music, Film |

Nicholas Galanin was born in 1979 in the town of Sitka in Alaska. His uncle and father taught him how to work with jewels and metals when he was a child. He’s also a grandson of renowned carver George Benson. Galanin started working in the Sitka National Historical Park when he was 18, as a receptionist.

In the park, when he was discovered to be drawing Tlingit art, he was told that he may study historical books on Russia only during working hours.

As a result, he took a leave of absence from his work to focus on his art. He considers this to be his final non-creative job. Galanin’s multimedia art and music highlight his modern art education while simultaneously acknowledging traditional methods. He values his uniqueness and culture, and as a result, he has developed a distinctive, impassioned, and independent voice.

He doesn’t feel that he is offering any new insight about America, but rather questions what it means to be American. His artwork is sourced from an era when the land had not yet received the name America and therefore represents something lost to modern society. With his artwork, he hopes to reject the usual narrative put forward in textbooks, and retell the story from the position of the indigenous people of the land.

And that wraps up our dive into the world of Native American art. We have seen how American Indian art started out as purely practical and tribal and how over time it has developed into something both personal and traditional. Today Native Americans are able to create whatever kind of art they want.

Take a look at our Native American paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Materials Did the Native Americans Use in Their Art?

Materials from animals were used such as hair from deer, llama’s droppings, quills from porcupines, and even sea lion whiskers were all utilized by the artist to add colors or textures to the completed work. American Indian artists had investigated and perfected nearly every natural medium such as rare stones, shells, metal, fiber from Milkweed, and birch bark.

Was Native American Art Tribal or Personal?

Art was at first just seen as a job well done. Artists were just considered good craftsmen. Although all these functions originally existed to serve the tribe, eventually it became more personal. Today artists use their art to depict their connection to the past, and the alienation they feel around them.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Native American Art – A History and Overview of American Indian Art.” Art in Context. December 17, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/native-american-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 17 December). Native American Art – A History and Overview of American Indian Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/native-american-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Native American Art – A History and Overview of American Indian Art.” Art in Context, December 17, 2021. https://artincontext.org/native-american-art/.