Bauhaus Art – Legacy of the Bauhaus School of Design

What is Bauhaus exactly? Bauhaus art is associated with a specific institution. The Bauhaus was undoubtedly the most significant progressive school of art in the 20th century and was responsible for the development of many prominent Bauhaus artists. Even after it closed under extreme pressure from the Nazi regime in 1933, the Bauhaus design school’s attitude to education and the link between society, art, and technology had a huge effect in the United States and Europe.

The History of Bauhaus Art

The Bauhaus style was inspired by 19th and early 20th-century creative tendencies including the Art Nouveau style and the various foreign versions like the Vienna Secession and Jugendstil, as well as the Arts and Crafts movement. All of these groups desired to blur the line between the applied and fine arts, as well as to reconnect imagination and fabrication; their heritage was represented in the romantic medievalism of the Bauhaus movement’s ideology during its formative days when it styled itself as some kind of craftsmen’s union.

By the mid-1920s, however, this ideal had given place to a focus on integrating industrial Bauhaus graphic design and art, and it was this focus that anchored the Bauhaus’ most innovative and significant achievements.

The institution is also known for its outstanding teachers, who have since spearheaded the development of contemporary art – and modern ideas – throughout the United States and Europe.

The Early Days of the Bauhaus Movement

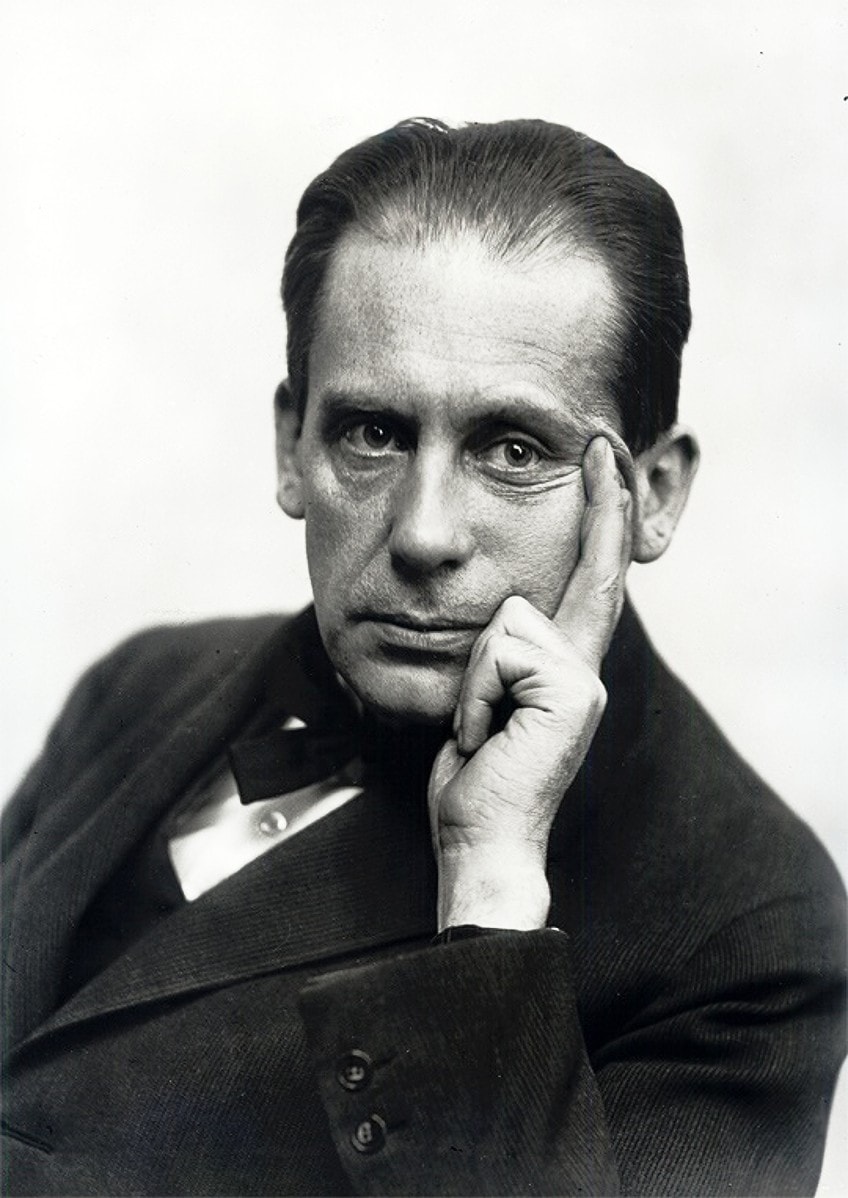

The Bauhaus, titled after a German phrase that means “house of construction,” was created in 1919 by architect Walter Gropius in Weimar, Germany. He took over a pre-existing school of Arts and Crafts in 1915, and the revolutionary new Bauhaus art school was founded four years later via the merging of this establishment with the Weimar Academy of Fine Art.

The Bauhaus style sprang conceptually from late 19th century impulses to combine fine and applied art, resist the industrialization of creativity, and improve education.

Simultaneously, the 1910s rise of Russian Constructivism provided a more urgent and aesthetically appropriate predecessor for the Bauhaus’ fusion of artistic and mechanical design. When the Bauhaus officially opened in 1920, it took up home in the old sculpture workshop of the Grand-Ducal Saxon institute, constructed in the Art Nouveau fashion.

Gropius urged the school to develop a fresh appreciation for craftsmanship and functional ability, implying a reversion to medieval ideals toward arts and crafts. He saw the Bauhaus movement as covering all forms of artistic expression, encompassing fine art, industrial designs, Bauhaus graphic design, Bauhaus interior design, typography, and architecture.

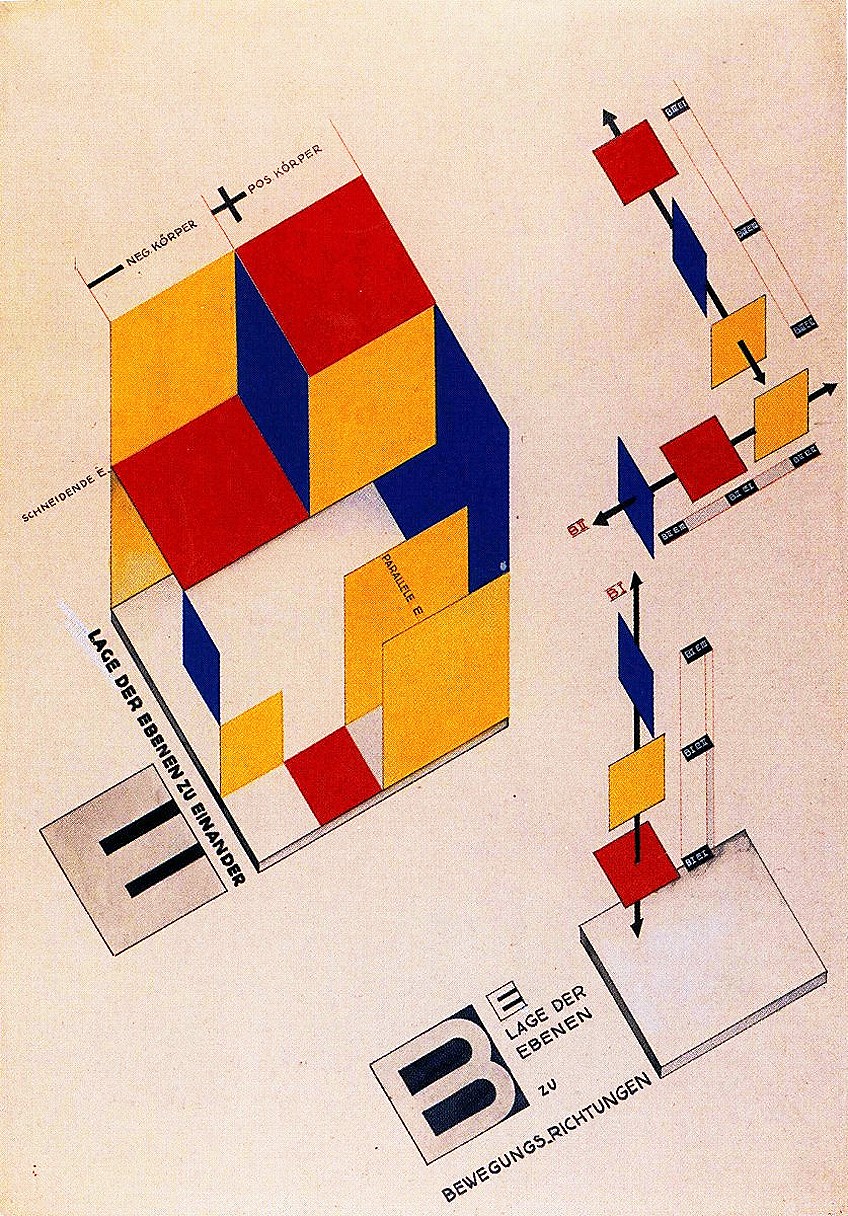

Bauhaus Styles and Concepts

The school’s strategy was centered on its innovative and impactful curriculum. Gropius described it as a wheel with rings, with the outer circle chosen to represent the six-month preparatory course launched by Johannes Itten that focused on the foundational facets of design, particularly the differing characteristics of varied shapes, colors, and substances.

The two middle circles signified two transitional three-year courses that concentrated on form-related challenges, as well as a curriculum of hands-on, workshop-based training centered on practical trades and techniques.

These seminars stressed functionalism, particularly the use of basic geometric shapes that could be easily replicated, which would become a theoretical centerpiece of modernist design and architecture in the coming decades. Courses specialized in constructing developments were at the hub of the wheel, educating students on the fundamentals of architecture, construction, and engineering, but with a focus on skills and craftsmanship that were thought to have been lost in contemporary building procedures.

One of the primary goals of the teaching method, which was used across all courses, was to reduce competitive inclinations and to encourage not just creative abilities but also a feeling of collaboration and common goals.

The Faculty of the Bauhaus

The phenomenally skilled professors that Gropius had drawn to Weimar were in charge of designing and delivering this curriculum. Gropius’ earliest choices were avant-garde artists Johannes Itten and Lyonel Feininger, as well as sculptor Gerhard Marcks.

Itten was especially crucial to the school’s formative ideology: with his Expressionism experience, he was behind much of the first focus on romantic medievalism that distinguished the Bauhaus, notably the preparatory course, which he developed.

His Expressionist and mystical proclivities famously placed him at odds with Gropius’ analytical, sociologically minded attitude, and the two quickly clashed. Itten had gone by 1923, to be succeeded by László Moholy-Nagy, a more fitting kindred personality to Gropius; Moholy-Nagy reshaped the curriculum that incorporated technology and the social role of art.

Nevertheless, during the duration of its short existence, the Bauhaus absorbed a variety of stylistic influences.

Though names like Moholy-Nagy are today identified with the technical philosophy of Constructivism, other initial choices encompassed Expressionist and Expressionist-influenced artists like Paul Klee and Wassily Kandinsky. They also featured artists working in many mediums, ranging from sculpture to dancing, such as Oskar Schlemmer and Georg Muche.

The Bauhaus Movement in Dessau

The Bauhaus relocated to the German factory city of Dessau in 1925, kicking off its most prolific period of development. Gropius constructed a new structure for the school that has become known not just as the Bauhaus’ spiritual emblem, but also as a hallmark of contemporary, structuralist architecture.

It was also at this point that the school established a division of architecture, which had been glaringly absent in its prior iteration. Gropius, on the other hand, was worn down by his labor and mounting confrontations with the school’s adversaries, especially conservative forces in German culture, by 1928.

He stepped aside, handing over the reins to Swiss architect Hannes Meyer. Meyer, who oversaw the architecture faculty, was an enthusiastic communist who instilled his political beliefs in student groups and educational initiatives. The institution increased in strength, but Meyer’s Marxism came under fire, and he was fired as director in 1930. After municipal elections in Dessau brought the Nazis to power in 1932, the school was once again shuttered and transferred, this occasion to Berlin, where it would remain for the remainder of its life.

The Bauhaus was revived temporarily in Berlin under the guidance of architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, a well-known champion of functionalist design who, like Gropius, was later connected with the so-called International Aesthetic.

Mies van der Rohe, on the other hand, had to contend with significantly fewer facilities than his predecessors, as well as a faculty devoid of many of its finest stars. He sought to remove politics from the school’s program, but this temporary rebranding effort failed, and when the Nazis took national power in 1933, the school was shuttered indefinitely due to severe political harassment and intimidation.

After the Close of the Bauhaus Design School

The Bauhaus’ impact would spread as far as its previous teachers in the decades after its demise, many of them were forced to depart Europe as the suffocating impacts of fascism took control. Gropius moved to the United States in 1937 and lectured at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design, where he was regarded as crucial in spreading the International Architectural style to America.

Josef Albers had been named director of the painting school at the illustrious Black Mountain College in North Carolina four years before, where his pupils included Cy Twombly and Robert Rauschenberg. In 1933, after fleeing Germany, László Moholy-Nagy founded the Institute of Design in Chicago.

The Bauhaus’s national heritage was also revitalized in the years following WWII, with the establishment of the Hochschule für Gestaltung in Ulm in 1953. This institution was the ideological heir to the Bauhaus movement in many aspects, with renowned Bauhaus pupil Max Bill selected as its first head.

Moholy-Nagy, Bill, and Albers were particularly influential in modifying the Bauhaus ethos to a modern era: Moholy-Nagy and Albers reshaped it into one more appropriate to a contemporary research institution functioning in a market-oriented society, while Bill was instrumental in propagating geometric abstraction all through the globe in the shape of Concrete Art, a movement that succeeded Constructivism.

Key Ideas of Bauhaus Design

The Bauhaus was founded in the late 19th century, in response to concerns about the vapidity of contemporary production and the loss of social importance of art. The Bauhaus artists sought to reconcile fine art and utilitarian design by developing practical things with the essence of works of art.

Despite its rejection of many features of traditional fine-arts education, the Bauhaus was strongly interested in philosophical and conceptual perspectives on its topic.

Various components of artistic and Bauhaus graphic design schooling were merged, and the Renaissance-era hierarchy of the arts was leveled: the utilitarian crafts – architectural and Bauhaus interior design, fabrics, and woodwork – were positioned on a level footing with fine arts like painting and sculpture. Given the Bauhaus’s emphasis on both high art and utilitarian craft, it is not surprising that many of its most important and long-lasting successes were in domains other than sculpture and painting.

The decor and utensil design features of Marcel Breuer, Marianne Brandt, and others prepared the path for the fashionable simplicity of the 1950s and 1960s, while builders such as Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Walter Gropius were regarded as early pioneers of the equally stylish International Style that is so significant in architecture today.

The Bauhaus method of teaching, with its emphasis on experimentation and problem-solving, has had a huge influence on current art education. It has resulted in a reimagining of the “fine arts” as “visual arts,” as well as a reworking of the artistic method as more comparable to a scientific science than a humanistic topic like history or literature.

Important Bauhaus Artists and Artworks

The Bauhaus movement represents one of the most important design philosophies of all time, marrying utilitarian design with aesthetic enjoyment to create a new art form capable of bringing beauty to daily products and beyond. It was a watershed moment in graphic design. Typography, layout, and the use of form and color were being reinterpreted in ways that would have a lasting influence on graphic design long into the twenty-first century.

The Bauhaus movement and its contemporary style had a huge impact on art and graphic design, with the time’s innovation and ideological upheavals influencing how we create to this very day.

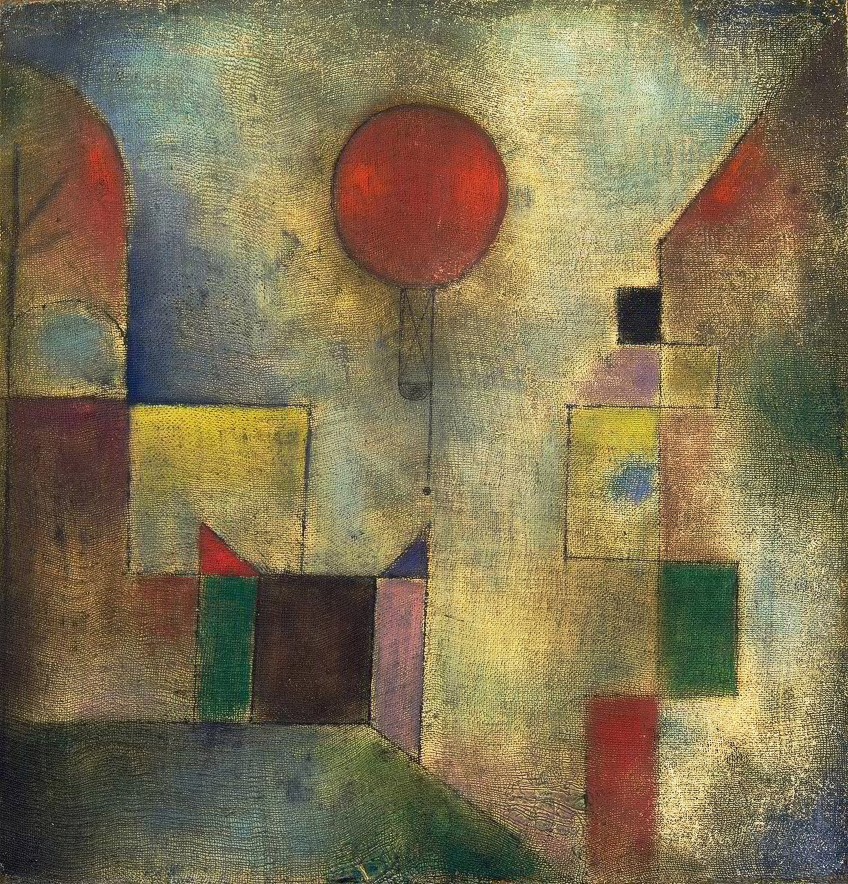

Red Balloon (1922) by Paul Klee

| Date Completed | 1922 |

| Medium | Oil on Gauze |

| Dimensions | 32 cm x 31 cm |

| Current Location | The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum |

Paul Klee was a visionary whose work blended remarkable formal inventiveness with a strange type of primal innocence. He was one of the most accomplished and intriguing painters affiliated with Bauhaus art and design. In this 1922 painting, fragile, transparent geometric figures – rectangles, squares, and domes – are highlighted in primary color gradations. A solitary red circle hovers in the upper middle, exposing itself to be the eponymous hot-air balloon upon closer study. This illustrated flourish shows Klee’s playful, correlative use of Bauhaus’s famed geometric compositional structures.

The focus of the artist’s distinctive style changes tensely between the abstract and the representational, between narrative connection and mystical symbolism. The luminous forms, suggestive of stained glass, are arranged asymmetrically to produce an aesthetic rhythm governed by horizontal, vertical, and diagonal lines that appear both organized and unplanned.

Klee, who was born in Switzerland in 1879, was involved with various modernist and Expressionist groups in Northern Europe from the 1900s and through the 1910s, including Der Blaue Reiter, before accepting a position at the Bauhaus in 1921, where he taught mural artwork, bookbinding, and other subjects.

His art lessons were published in the Bauhausbücher series in his Pedagogical Sketchbooks (1925). This work, which began with the line “an effective line on a walk, constantly moving, without objective,” became enormously impactful, creating his renown as one of the excellent theorists of contemporary art as he tried to assess every last possible combination of his restless lines. The line, For Klee, which grew from a single position, was an independent, impulsive agent whose movement shaped the formation of the plane.

This analogy for the emergence of creative form became a central element of Bauhaus design theory, inspiring many of Klee’s colleagues, notably Anni Albers and Klee’s longtime friend Wassily Kandinsky. Klee’s participation in the Bauhaus from 1921 until his retirement in 1931 debunks preconceptions of the school as unduly focused on logic and formal, rigid procedures.

Klee’s oeuvre influenced other painters in Europe and America, notably Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell, Kenneth Nolan, Norman Lewis, and William Baziotes, who saw it as simultaneously sophisticated and primal, realistic and otherworldly. “Almost everyone, regardless of whether conscious or not, was studying Klee,” Clement Greenburg wrote in 1957.

Yellow-Red-Blue (1925) by Wassily Kandinsky

| Date Completed | 1925 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 63 cm x 92 cm |

| Current Location | Musée National d’Art Moderne, |

This intricate work is organized around three primary visual sections, which are emphasized by red, yellow, and blue forms. These, in turn, establish two main zones of visual focus, one on the right-hand side of the panel, made by the interconnecting blue circle and red cross, and one on the left, formed by the yellow rectangle impressed against a darker shade of ochre. Color and shade effects imply variation in perceptual weight and location in space, as the lightness of the yellow contrasts with the deeper red tones, extending further into blue and purple.

A meshwork of linear and curved lines interact throughout the canvas, as though reenacting the fight of energy established between the many fundamental hues. Wassily Kandinsky was born in Moscow in 1866 and moved to Germany before the late 19th century, where he became a crucial figure in the advancement of Northern-European Expressionism over the next few years; his 1903 painting Der Blaue Reiter inspired the Expressionist art group of the same name.

Kandinsky moved to Germany and started lecturing at the Bauhaus in 1922, after a six-year stint in Soviet Russia sandwiching the revolution (1914 – 1920), by which point his artwork had progressed towards a refined form of abstraction. He exposed his pupils to the examination of fundamental colors and the structure of their relationship as a tutor on the preparatory level.

In 1923, he created a survey in which respondents were asked to complete a triangle, square, or circle with the most suitable primary color to discover an inherent qualitative link between certain forms and colors. The consequent red square, yellow triangle, and blue circle became a typical Bauhaus pattern, which Kandinsky investigated and manipulated in this well-known piece, changing it into a poetic representation of the link between aesthetic and melodic expression.

The same concepts impacted his renowned essay “Point and Line to Plane” (1926), which was motivated by recent research on Gestalt psychology, a prominent topic of debate at the Bauhaus at the time.

Kandinsky was intrigued by how particular line, color, and tone mixtures may have intrinsic psychological and spiritual consequences, which were then linked to specific musical melodies. Nevertheless, as art expert Annagret Hoberg points out, the artwork’s ramifications go beyond this, into more representational realms: “The two centers evoke anthropological overtones. While the arrangement of the circles and lines in the yellow field suggests a human profile, the interweaving of blue and red forms with the black diagonal is evocative of the subject of Saint George and the Dragon.”

Maybe it is these more human connections that explain Kandinsky’s abstract works’ legendary status in contemporary art history: as Hoberg points out, Yellow-Red-Blue “expended a sway on subsequent modernism, which include, for instance, Barnett Newman’s series Who’s Afraid of Yellow, Red, and Blue (1969).”

Club Chair (1925) by Marcel Breuer

| Date Completed | 1925 |

| Medium | Steel and Canvas Upholstery |

| Dimensions | 72 cm x 78 cm x 71 cm |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

Marcel Breuer’s famous chair is a novel twist on the classic upholstered ‘club chair’ of the 19th-century drawing room, a sleek fusion of curved, overlaying stainless steel tubes and tight rectangular textile panels hovering like geometric objects in space. The chair was characterized by the artist as “my most severe piece is the least artistic, most rational, least ‘cozy,’ and most mechanistic.”

It was, however, his most significant work, demonstrating the breakthrough innovations in functional design that distinguished the Bauhaus by the mid-1920s. It satisfied all of the criteria of the school’s design ethos, being lightweight, readily movable, and mass-produced, with its components placed with a simplicity that made its structure and function clearly apparent.

Breuer, who was born in Hungary in 1902, was one of the initial Bauhaus generation’s youngest participants. He left his hometown of Pécs at the age of eighteen and enrolled as one of the school’s first pupils at Gropius’ revolutionary new institution in 1920. He was chosen as a prodigy and given command of the woodwork shop, and after a brief stay in Paris, he returned to the Bauhaus as a teacher in 1925.

Breuer, an avid biker, considered the bicycle the epitome of contemporary design and was captivated by his bicycle’s curving handlebars, which were constructed of a new type of tubular steel produced by the Mannesmann manufacturing business. He recognized that the same substance, which could be twisted without cracking, might be employed in furniture design, and the “club chair” was born as a consequence of this epiphany. Breuer founded the business Standard Möbel in 1927 to mass-produce his furniture.

The chair’s colloquial name celebrates the artist Wassily Kandinsky, who adored it when he first encountered it in Breuer’s workshop. Breuer’s chair was “the first-ever chair to use a bent-steel frame and it heralded the start of a revolutionary era in contemporary furniture with a form that retains a futuristic look even now,” according to the art historian Seamus Payne.

After WWII, the Italian manufacturer Gavina began manufacturing the chair, confirming its long-term effect on design history and selling it as the “Wassily Chair.” In 1968, the American manufacturer Knoll acquired Gavina and started producing the Model B3, which is still available today.

Universal Bayer (1925) by Herbert Bayer

| Date Completed | 1925 |

| Medium | Typeface |

| Dimensions | N/A |

| Current Location | N/A |

Herbert Bayer’s Universal Bayer font, a classic of International Style typography, adopts a simple style of the Bauhaus font. At the very same time, the style’s simplicity shows Bayer’s concern for improved readability, providing a considerable number of negative spaces between letters in contrast to conventional German typography’s constricted calligraphic scripts.

Bayer intended written language to reflect the simplicity of speech, and chose just lower-case letters for this styling since there was no phonetic difference between the lower and upper case. Because each character has the same dimension, they defined transferable places on the page.

As a result, the type was relatively simple to use and could be converted to typewriter keyboards and typesetting equipment. These design elements wonderfully encapsulate the Bauhaus emphasis on utility and mass production. Bayer, like Breuer, was a young representative of the Bauhaus’ golden generation, having been born in Austria in 1900. He began his career as an architect and, in the late 1910s, was a member of the Darmstadt Artist’s Colony, where he was influenced by the Jugendstil or Art Nouveau ideas of that group, as well as its focus on the concept of the ‘whole work of art.’

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=elKJuaK3CHs

However, in 1920, Bayer became interested in Gropius’ new venture and joined the school in 1921, learning under Kandinsky, Klee, and Moholy-Nagy. After returning to the Bauhaus as a teacher in 1925, he was named head of printing and advertising during the Dessau era. After Gropius ordered him to produce a font that could be used in all Bauhaus publications, he created the Universal Bayer typeface. At the time, most German printers still used Fraktur, a striking Gothic typeface devised in the 16th century for Albrecht Dürer’s woodcut Triumphal Arch (1526).

Bayer conveyed the spirit of a new cultural phenomenon that rejected backward-looking nationalism in favor of international modernism, a movement championed by the Bauhaus and eventually wiped out by the Nazis, by removing the ornamentation from German letters.

His design was also supposed to adhere to a famous Bauhaus compositional principle, in which letters were organized in diagonal lines pushing upwards over the page, wrapped around objects, and highlighted in bright colors.

Although Bayer’s font was never cast in metal, its effect was extensive and long-lasting. Along with being at the frontline of advancements in International Style typography from the 1920s to the 1950s, affecting typefaces such as Architype Schwitters, it is also the motivation for Google’s font. The font can also be seen in several Bauhaus posters. Herbert Bayer’s Bauhaus poster for the Kandinsky Exhibition in 1926 is an example.

Photogram (1926) by László Moholy-Nagy

| Date Completed | 1926 |

| Medium | Gelatin silver print |

| Dimensions | 23 cm x 18 cm |

| Current Location | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York |

The artist’s hand appears to arise out of the darkness and float in space in this cameraless snapshot, or “photogram,” behind a grid of flaming white lines that cross with his fingertips. The figures appear to emerge on the paper not merely as though gaining shape from the interaction of shadow and light, but also as dematerialized echoes of tangible objects: they become traces of physical touch.

Various European designers, such as Christian Schad and Man Ray, dabbled with the photogram – a phrase invented by Moholy-Nagy – under alternative titles during the 1910s and 1920s, but through Moholy-efforts, Nagy’s these efforts of Abstract Photography became inextricably tied with the Bauhaus’ groundbreaking ideology.

In 1895, László Moholy-Nagy was born in Hungary. He came to Germany in 1920, and Gropius requested him to take over the institution’s basic curriculum from Johannes Itten in 1923, with his artistic renown already established. Moholy-photograms became emblems of Bauhaus innovation, even though he worked in a variety of mediums. These works, which were created by putting things on photo-sensitive paper subjected to ambient light, make light “the material of plastic expression,” in the artist’s terms.

Despite the fact that photography was not formally part of the Bauhaus’s curriculum, Moholy-Nagy worked in a one-man photographic department, and his zealous enthusiasm led many of the school’s teachers and students to experiment with photography.

Moholgy-Nagy, who was fascinated by light, continued to investigate the potential of the photogram throughout his career, most prominently at the Chicago School of Design, which he created in 1939 after relocating to the United States.

Here, “light laboratory” classes were required, and Moholy-work Nagy’s influenced many future North-American artists, including Arthur Siegel. Moholy-photograms Nagy’s are testaments to the Bauhaus’s pioneering technological and creative ethos, particularly its devotion to investigating the fundamental qualities and abilities of many artistic mediums. In essence, they are investigations of photosensitivity principles in their purest, most unadulterated form, and so encapsulate the “form-follows-function” mentality currently associated with the Bauhaus and the larger Constructivism movement.

With that, we conclude our investigation of Bauhaus Design. The Bauhaus School influenced many aspects of applied art, such as Bauhaus interior design and Bauhaus graphic design. Bauhaus artists and their work not only changed the artistic landscape in its time but for many years to follow.

Take a look at our Bauhaus style webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Bauhaus?

The Bauhaus was without a doubt the most important progressive art school of the 20th century, and it was responsible for the development of many well-known Bauhaus artists. The Bauhaus design school’s perspective toward education and the relationship between society, art, and technology had a tremendous impact in the United States and Europe, even after it disbanded under Nazi pressure in 1933. The school’s strategy was based on its cutting-edge and effective curriculum. The outer circle was selected to represent the six-month preparation school founded by Johannes Itten that concentrated on the basic components of design, notably the varying features of different forms, colors, and materials, according to Gropius.

What Defines the Bauhaus Style?

Art Nouveau and its numerous foreign variants, such as the Vienna Secession and Jugendstil, as well as the Arts and Crafts movement, influenced the Bauhaus style in the 19th and early 20th centuries. All of these organizations wanted to blur the lines between practical and fine arts, as well as integrate imagination and manufacturing. This history was reflected in the romantic medievalism of the Bauhaus movement’s philosophy during its early years when it posed as a craftsmen’s union.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Bauhaus Art – Legacy of the Bauhaus School of Design.” Art in Context. April 14, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/bauhaus-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 14 April). Bauhaus Art – Legacy of the Bauhaus School of Design. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/bauhaus-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Bauhaus Art – Legacy of the Bauhaus School of Design.” Art in Context, April 14, 2022. https://artincontext.org/bauhaus-art/.