American Regionalism – The Drive for Accessible American Art

What is Regionalism art, and who were the pioneers of American Regionalism? The early 20th century produced many iconic art movements in the United States that contributed to making art more accessible to a wider audience and assuring the American public in light of the economic distress caused by the Great Crash of 1929. American Regionalism was one such art movement that emerged in the 1930s, and despite its short-lived popularity in America, its impact was recognized as one of the art forms that appealed to American sensibilities. In this article, we will explore the origin of American Regionalism, including the pioneering figures who shaped the art style, and the movement’s influence on the contemporary era. Keep reading for all you need to know about American Regionalism!

Defining American Regionalism and Its Origins

What is Regionalism art, and what does it have to do with American Modernism? American Regionalism refers to the 20th-century art movement that emerged in the early 1930s and lasted until the middle of the decade. Although it was short-lived, the movement remains an important period in modern art in America that focused on portraying the realistic experiences of small towns and rural areas in America. At the forefront of American Regionalist imagery were depictions of the American Midwest.

So, how did this art movement develop, and why? The 1930s in America was a period of socio-political turmoil and economic crisis for many people. This era was known as the Great Depression, which affected many families, and as such, the genre of American Regionalism emerged to remind people of the traditional American lifestyle as a form of comfort. The movement was most popular between 1930 and 1935, after which it receded with World War II. There was no particular style to American Regionalism, however, the themes within the movement remained consistent such that it opposed the main art styles seen in French art.

Artists behind the American Regionalist movement rejected the modern styles of European art in favor of subjects that expressed aspects of the American heartland. Styles in American Regionalism included realistic, figurative, and narrative artworks that reverted to the element of storytelling fused with familiar subjects rendered with precision. The style of American Regionalist art appealed to many people at the time, however, its popularity declined after its style was adopted by totalitarian regimes in Europe that utilized figurative and realistic subjects in propaganda. The style of American Regionalism became problematic and was viewed as retrogressive instead of modern. As such, it was entirely rejected when Abstract Expressionism emerged in the 1940s.

The themes in American Regionalism addressed different regional variations of cultures from the American Midwest that had an appeal of authenticity. Federal agencies such as the WPA supported the promotion of American Regionalism art but were halted when Socialist Realism took over, joining hands with propaganda.

This does not mean that all artists stopped creating realist and figurative work altogether, instead, a few artists such as Norman Rockwell and Andrew Wyeth continued to produce similarly styled works.

The Socio-Political Landscape Behind American Regionalism

To develop your understanding of the movement, it is useful to review its context. It is key to note that American Regionalism was very much an American art style that emerged before World War II. This was also a period when American artists were attempting to establish aesthetics for what American art should look like. Styles that emerged from the School of Paris and the Armory Show were rejected by followers of American Regionalism, who favored academic styles such as Realism. The reason why the movement gained popularity in the first place, was the context of the Great Depression, which saw a vast majority of people living in rural landscapes and only a few of the population occupying cities like Chicago and New York.

American Regionalism paintings also feature scenes of rural America, which developed organically rather than through a set manifesto in the movement. Artists who were recognized as the “Regionalist Triumvirate” included Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton, and John Curry who strongly rejected abstraction due to its cultural isolation and foreign origin. The Regionalist Triumvirate previously studied art in France during the 1920s, when they were influenced by artists such as Georges Seurat, Stanton MacDonald Wright, and the Neue Sachlichkeit movement. Artists such as John Curry were influenced by Gustave Doré and Peter Paul Rubens, which fueled his need to change the American art style after Grant Wood remarked in a letter that he felt that the American art world was too undeveloped to produce artists.

Following this, the crash of the stock market in 1929 spurred a complete social and cultural change in America after it left numerous people unemployed and vulnerable.

This was perhaps the first-moment people were outwardly disappointed in the industrialist culture promoted by “big city lights”, which saw most townspeople reflect on “the good old days” with a longing for simple, yet honest work. The artists of the Regionalist Triumvirate began to create art that reflected on the cultures of their native homelands and saw Benton create works that celebrated Missouri, Wood produce scenes of Iowa, and images of Kansas created by Curry. These themes and stories, considering the economic state of America, are what fueled the art movement known as American Regionalism.

Regionalism vs. Urbanism: Contrasting Artistic Perspectives

American Regionalism was only one artistic perspective that shaped early 20th-century art and offered a unique view of society in the context of small rural American towns and traditional landscapes. At the heart of the movement was regionalism, which celebrated traditional cultures and small-town life. Artists who followed the movement portrayed the heartland to evoke feelings of nostalgia, a connection to nature, belonging, and simplicity through idyllic scenes.

Such Regionalism paintings were connected to regional identity and pride that was viewed as an escape from the bustle of urban life. In contrast to regionalism, there was also urbanism, which celebrated the cosmopolitan appeal of city life and immersed viewers in the urban landscapes of America. Famous urban artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Edward Hopper have explored modern aesthetics in urbanist art to highlight the complexity of industrialization and its tremendous impact on the experience of urban life.

Themes such as isolation, architecture, and alienation were present in urbanist art, which provided a tension between American Regionalism, as a distinct culture that signified “progress”.

Regionalism in itself was a longing for the simpler past embodied by regional identities that provided people with more comfort than the idea of change and technology, which eventually uprooted many people’s lives in 1929. Urbanism captured the fast-paced nature of change and the role of the individual in the urban environment. Together, both regionalism and urbanism showcase the American experience through two perspectives that were born from shifts in society, culture, and the economy.

Pioneers of American Regionalism

Now that you understand what American Regionalism entails, you can now explore some of the early pioneers of American Regionalism, whose contributions to the movement shaped its visual characteristics.

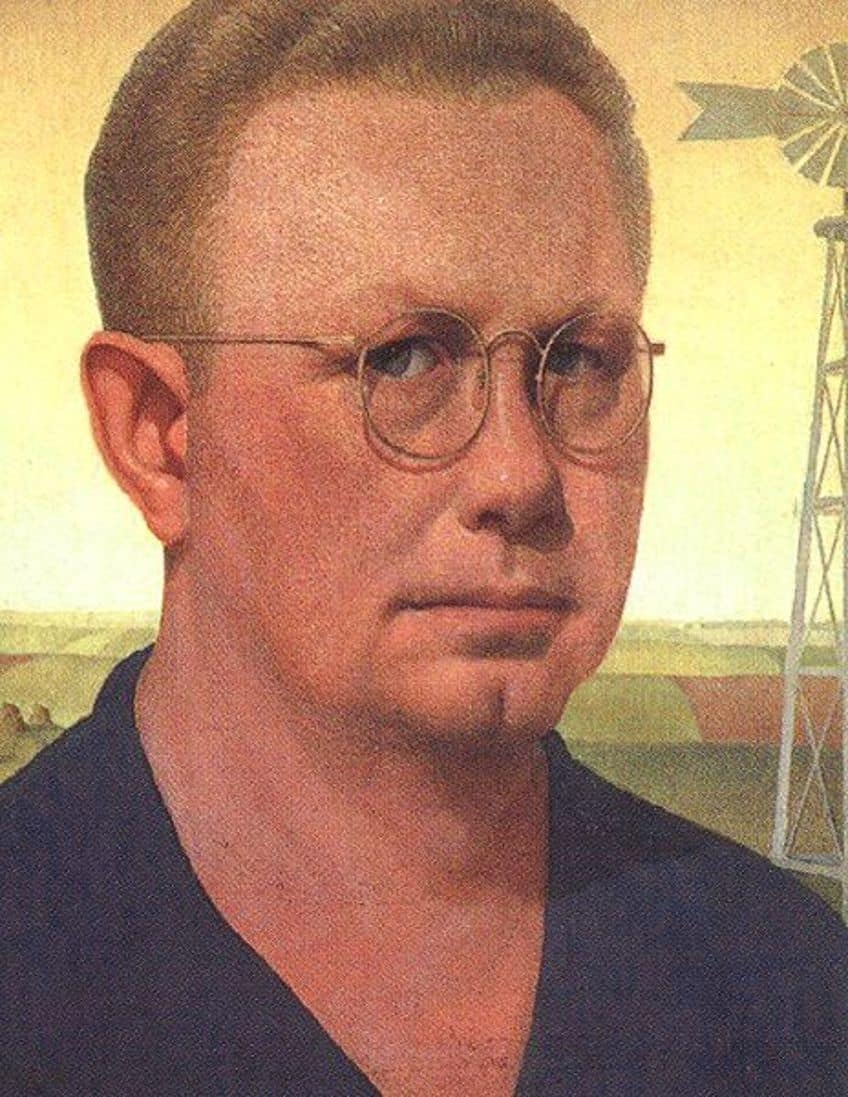

Grant Wood: Capturing the Essence of Rural Life

| Artist Name | Grant DeVolson Wood |

| Date of Birth | 13 February 1891 |

| Date of Death | 12 February 1942 |

| Nationality | American |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, American Regionalism, Social Realism, Realism, and figurative art |

| Mediums | Painting and design |

Grant Wood was the most famous American Regionalism artist of the 1930s, who was recognized for his figurative Regionalism painting American Gothic (1930).

Wood specialized in painting, and design, and was a craftsman, who trained in Paris at the Académie Julian.

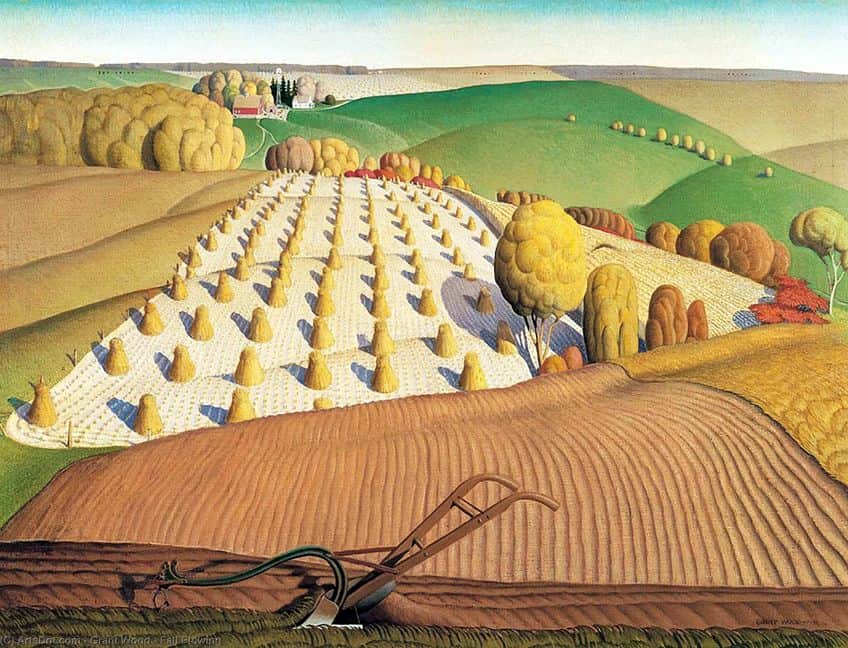

Wood’s artistic career was defined by his passion for rural America, including mythical subjects, cornfields, and other themes from American history. Wood’s approach to Regionalism painting was realistic, although he did practice Impressionist styles at the academy, he eventually abandoned it completely to create detailed and figurative paintings such as American Gothic.

American Gothic (1930): Unraveling the Symbolism

| Date | 1930 |

| Medium | Oil on beaverboard |

| Dimensions (cm) | 74 x 62 |

| Where It Is Housed | Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois, United States |

What made one of Wood’s greatest works so special? American Gothic was painted in 1930 and took the art world by storm after it was first exhibited at the Art Institute of Chicago. What made the painting stand out was its striking use of Realism and precision, which offered an honest approach to American art. The painting portrays a farmer posed with his daughter in the frontal profile. The models in the painting were identified as Wood’s sister and his dentist B.H. McKeeby, conveys the ideal image of hard-working rural citizens. The painting embodied the idealistic nostalgia of the Midwest, which was also criticized for its superficiality.

The Regionalism painting of the two figures is also bizarre in that they illustrate the models as stiff, which has been compared to “tintypes” from a family album.

The home in the background of the figures is illustrated in the Carpenter Gothic style, which was inspired by Wood’s trip to Eldon, Iowa. The dentist’s hay fork symbolizes manual labor and the woman’s apron illustrates a colonial print, which symbolizes 19th century America. The intention behind the work was to portray a positive image of the Midwest and embody rural American values to reassure the people during the Great Depression. However, many critics viewed the work as a possible satirical commentary on Midwestern people, who were perceived as out of touch with modernity.

Landscapes of the Midwest greatly inspired Grant Wood and served as a record of a time left behind due to industrialization and modernity. Wood created many landscapes of Iowan scenes throughout the 1930s as a homage to the old masters of painting and the decline of rural America spurred by Big Agriculture, industrialization, and homogenization. With slight influences of surrealist styles, Wood also created miniaturist works such as Stone City, Iowa (1930) and Arbor Day (1932), which portrayed these landscapes as untouched and safe.

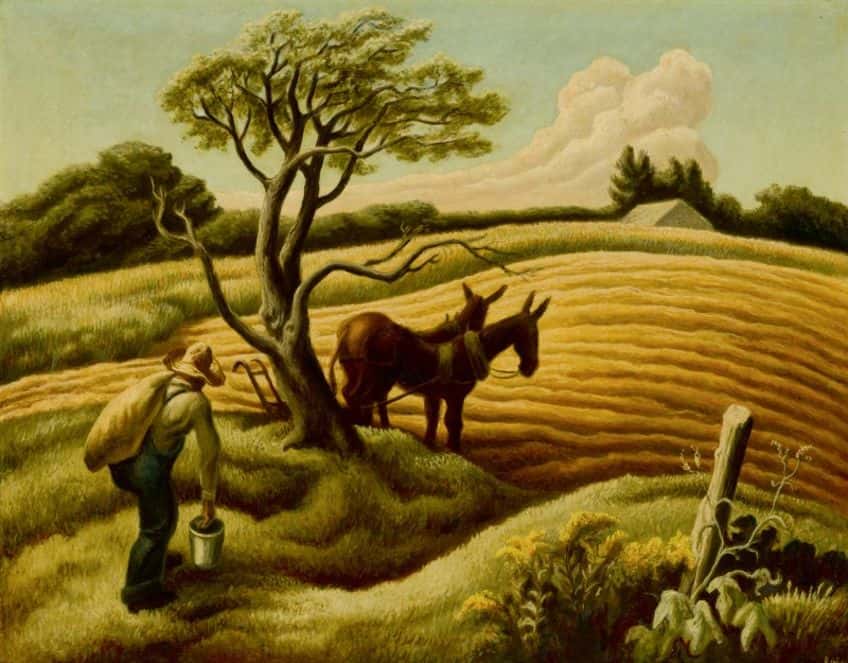

Thomas Hart Benton: Depicting Dynamic Vistas, Urban Life, and Rural America

| Artist Name | Thomas Hart Benton |

| Date of Birth | 15 April 1889 |

| Date of Death | 19 January 1975 |

| Nationality | American |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, American Regionalism, Regionalism, Synchromism, and American Modernism |

| Mediums | Painting, mural art, and printmaking |

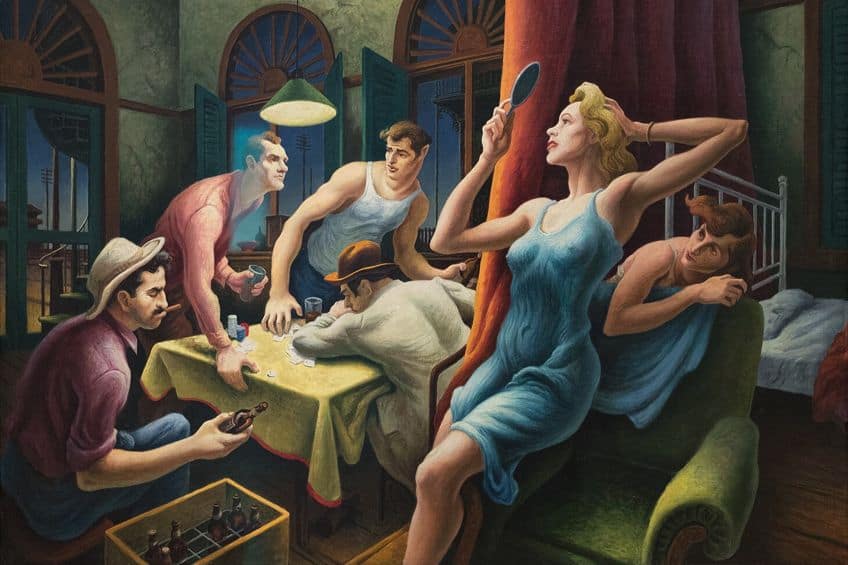

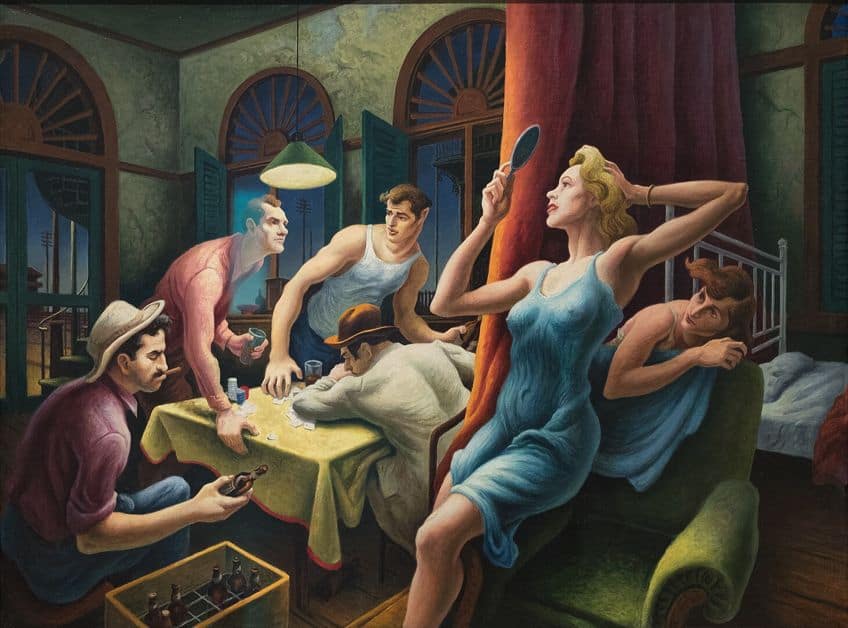

Thomas Hart Benton was among the most renowned American Regionalist painters of the 20th century, who was recognized for his depictions of urban life, rural scenes, labor, farming, portraits, factories, and landscapes.

According to Benton, his Missouri mural was one of his best works that demonstrated his ambition to inspire many Americans during a period of tribulation.

Benton’s position as an artist was unique since he battled with following the path of a congressman, like his father, and his great uncle, who was a senator. Benton also trained in art in Paris and settled in New York for 20 years and later in Martha’s Vineyard, where he captured the different scenes of the Midwest and American South.

America Today (1930 – 1931)

| Date | 1930 – 1931 |

| Medium | Egg tempera with oil glazing over Permalba on linen mounted to 10 wood panels with honeycomb interiors |

| Dimensions (cm) | 233.7 x 406.4 |

| Where It Is Housed | The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, United States |

One of Benton’s most famous multi-mural works is America Today (1930-1931), which is currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The mural spans an entire room with paintings on all four walls comprising 10 panels that bring to life the heart of America in the 1930s and the many complex regional nuances. Benton was commissioned by the director of the New School for Social Research in New York, Alvin Johnson, who wanted the piece for the new urban Joseph building.

The commission was unpaid; however, he was provided with all the materials he needed to create this novel mural.

According to Benton, every aspect of the mural was inspired by people and scenes he witnessed on his travels. No part of the mural was exaggerated as he managed to capture the essence of the Jazz Age, as well as the intense moments of industrialization through scenes such as farming, movie houses, saloons, crowded subways, and advertisements for tobacco and toothpaste. He also captured the moments when skyscrapers began towering over the city as hallmarks of urban life and promises of modernity.

Benton was also known to conscript students and friends while he traveled to rural towns to discover the realities of “true” America. Here, he found elements such as gritty working conditions, neglected homesteads, and dusty towns, which was a strong contrast to the realities of those living in Chicago and New York. Benton’s collection of lithographs also provides a detailed snapshot into the disappearing cultures of “old America” and features scenes with young people singing, conversations at the gate, gatherings at the county courthouse, and the lives of African American people. Around 1941, Benton was also dismissed from his position at the Kansas City Art Institute due to his homophobic comments.

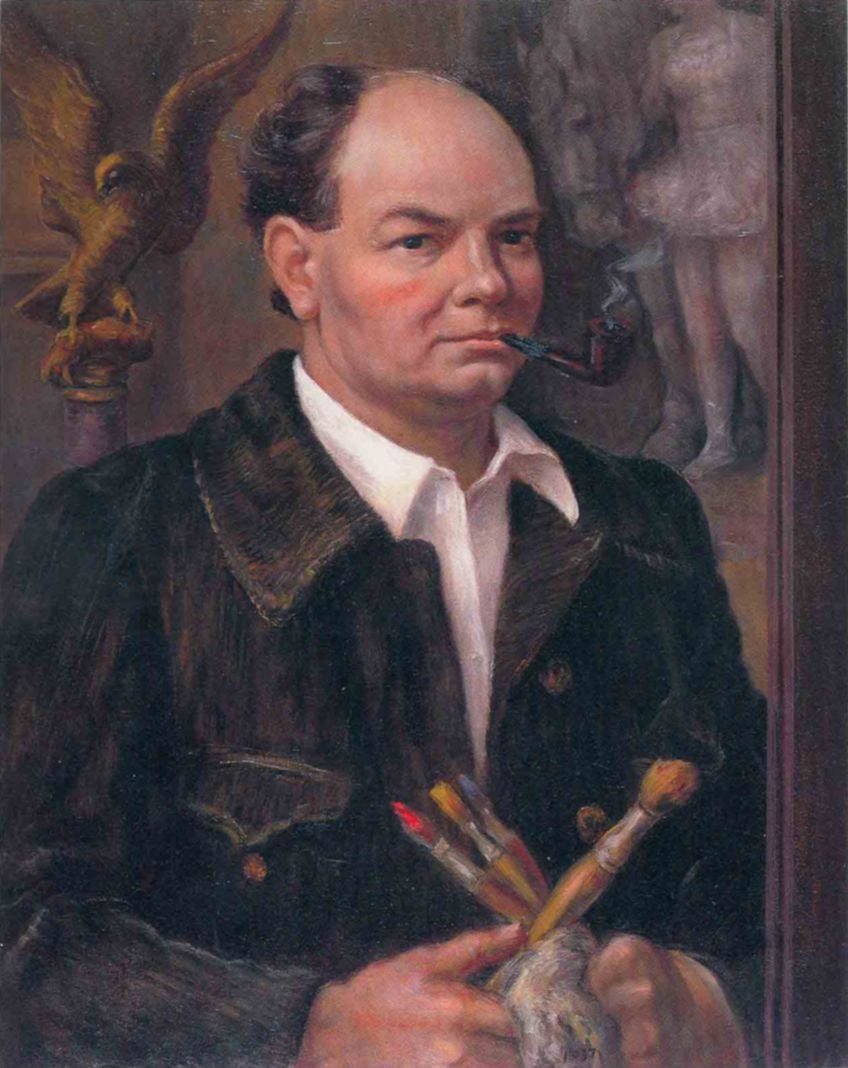

John Steuart Curry: Portraying the Drama of Rural America

| Artist Name | John Steuart Curry |

| Date of Birth | 14 November 1897 |

| Date of Death | 29 August 1946 |

| Nationality | American |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, American Regionalism, and Social Realism |

| Mediums | Painting, illustration, and design |

Among the top three painters in American Regionalism was John Steuart Curry, whose long-standing career produced many well-known Social Realist paintings.

Curry was recognized for his paintings of Kansas and contributions to book illustration and poster design.

Although Curry’s subjects were primarily Kansas-based scenes, his works were not as well received in the city as compared to other regions. His paintings included scenes with farm animals, natural disasters, and other subjects that Kansas citizens did not view in an acceptable light for representing Kansas. His work, Tragic Prelude (1942) was considered controversial and even banned from being exhibited on the walls of the capitol.

Tragic Prelude: Interpreting the Kansas Statehouse Murals

| Date | 1942 |

| Medium | Oil and egg tempera on the wall |

| Dimensions (cm) | 136 x 945 |

| Where It Is Housed | Kansas State Capitol, Topeka, Kansas, United States |

Tragic Prelude is one of the most famous works by Curry that was created for the Kansas State Capitol building’s second-floor rotunda. The mural portrays John Brown, an abolitionist, who holds a bible in one hand with the Greek alphabet of the apocalypse, indicated by the alpha and the omega. John Brown was charged with treason and hung after he spearheaded a raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859. On Brown’s other hand, Curry included a rifle, and together with the bible, referenced Beecher’s Bible as the abolitionist faces the Confederate and Union soldiers, who are portrayed as both living and dead.

Emigrants are also spotted traveling in wagons from east to west.

The composition and its many symbols represented the period between 1854 and 1860, which was recognized as the Bleeding Kansas era and was a prelude to the Civil War, in a battle that attempted to prevent Kansas from becoming a slave state. William Allen White attributed the title Tragic Prelude to the work to describe the history of Kansas. Other figures included in the work include Fray Juan de Padilla, a Franciscan missionary, Coronado, a conquistador, the first European settler, and a plainsman, who had just slain a buffalo. The mural was rejected by the Kansas Legislature, which caused Curry to leave the state behind in disgust, thus leaving the mural unfinished. The painting was only exhibited in the building after his death.

Influences and Legacy

Curry respected and appreciated with styles of artists such as Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet, and later went on to travel America with the Ringling Brother Circus, which led him to practice art at the University of Wisconsin as a resident. In the 1930s, he created many poster designs for Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s WPA program to promote war efforts. Curry’s painting style was largely defined by his ability to evoke emotion in Regionalist painting, which was celebrated and captured best when he depicted emotions such as despair and fear.

Curry was also influenced by the works of his contemporaries at the time, including the style of Grant Wood and Thomas Benton.

John Curry’s legacy on American Regionalism was profound since his idealized paintings of the Midwest celebrated the plentitude of the land, and as such, uplifted many people who were feeling the harsh impact of the Great Depression. Curry was also one of the first American Regionalists to receive a commission from the New Deal Works Progress Administration and produce a large-scale American Regionalist public artwork. His work was extremely sentimentalized and often misinterpreted as satire. Many people were first astounded by Curry’s work since it had no intellectual foundation, as opposed to other painters. Fast forward to the 1990s, Curry’s work regained popularity, which saw many adopting a newfound appreciation for his work.

Regionalism Beyond the Midwest

While these top three American Regionalists defined the foundations of the movement, there were many other important figures from beyond the Midwest, who contributed to the movement. These include William H. Johnson from the South, Maynard Dixon’s desert landscapes of the West Coast, and Andrew Wyeth’s exploration of Regionalism in New England. Below, we will explore these three figures, whose contributions provide new dimensions to understanding American Regionalism.

Maynard Dixon: West Coast Landscapes

| Artist Name | Maynard Dixon |

| Date of Birth | 24 January 1875 |

| Date of Death | 13 November 1946 |

| Nationality | American |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, American Regionalism, landscapes art, and the American West |

| Mediums | Painting and poetry |

Another famous American Regionalist painter was Maynard Dixon, whose animated landscapes of the American West have been praised as the finest works of the early 20th century.

Dixon was also a poet, who traveled to Southern Utah, the Zion National Park, the Salinas Valley, and Mount Carmel to capture the vast and complex socio-political landscapes of these regions.

His Social Realist paintings were created during the Great Depression, which featured less romantic landscapes of people who were displaced, strikers, and people suffering from depression. Among his best works include Antonio Mirabal (1931), Shapes of Fear (1932), and Old Chinatown (1937).

William H. Johnson: A Pioneer of Black Consciousness in Regionalism

| Artist Name | William Henry Johnson |

| Date of Birth | 18 March 1901 |

| Date of Death | 13 April 1970 |

| Nationality | American |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, American Regionalism, Harlem Renaissance, Expressionism, landscapes, and portraiture |

| Mediums | Painting |

William Henry Johnson was one of the greatest American artists of the early 20th century, whose career was informed by his experiences in France and his relocation across several continents.

Johnson was a key painter of the Harlem Renaissance, whose works were emotional, expressive, and distinct from other American Regionalists of his time.

After his return to the United States around 1938, he began producing works that reflected Afro-American cultures, folk art, and landscapes from his experiences of the South. At the forefront of his career was the idea of Black migrant consciousness, which became a key concept of the Harlem Renaissance. Johnson’s approach to Regionalism focused on the lived experiences of Black life and the disparities between the urban North and the rural South. Famous paintings by Johnson include Off to War (1941) and Homesteaders (1942), which were created after his return from Europe.

Andrew Wyeth: 70 Years of Realism

| Artist Name | Andrew Newell Wyeth |

| Date of Birth | 12 July 1917 |

| Date of Death | 16 January 2009 |

| Nationality | American |

| Associated Movements, Themes, and Styles | Modern art, American Regionalism, Realism, abstraction, and landscape art |

| Mediums | Painting and illustration |

Dubbed a Magical Realist by many critics for his uncanny approach to Regionalism, Andrew Wyeth was one of the most renowned American painters. Wyeth’s painting style was celebrated for its realistic yet meaningful approach to Regionalism, which made him one of the best artists of the mid-20th century.

Wyeth was inspired by his hometown culture in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and Cushing in Maine, which featured portraits of his family, friends, and familiar American landscapes.

Wyeth was also an illustrator and learnt draftsmanship before he even learned how to read. He developed his passion for rural landscapes in his teenage years, while taking lessons with his father, N. C. Wyeth. Some of Wyeth’s best paintings include Winter Fields (1942), Christina’s World (1948), and Trodden Weed (1951), which were created after his father’s death and illustrate the melancholic shift in his regionalist paintings.

Regionalist Themes and Subjects

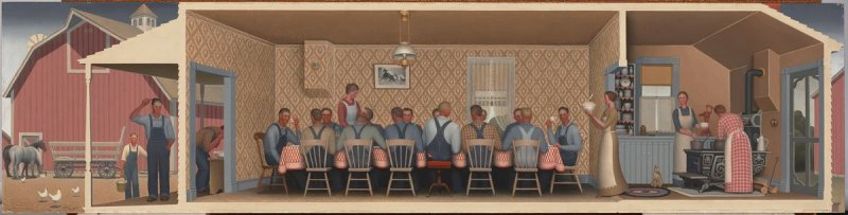

To summarize, there were a select few themes included in American Regionalism art. These themes included the idyllic depiction of rural landscapes, which romanticized the history and culture of the American Midwest and highlighted the public’s longing for easier days when economic struggle did not have such a tremendous impact on people’s livelihoods.

Artists of the movement also aimed to represent the cultural variations among rural communities, including scenes from everyday life, which brought many people comfort.

Everyday scenes included scenes of labor, communal gatherings, farming, and domestic settings that emphasized the calm nature of rural life, yet highlighted the perseverance of the people who came from such communities. Portraiture was also a popular form of representing rural America. This was to showcase the variety of emotions experienced by people from the Midwest and other rural parts of America, where people did not live in luxury or flaunt their belongings. Rather, portraits showcase the individuals behind the land who contributed to the support of their families and the community.

American Scene Painting

It is also useful to understand the position of American Regionalism in American Modern art. The movement was understood as part of three main categories, which encompassed Regionalism, Abstract art, and Social Realism. In the 1930s, American Regionalism and Social Realism united under the genre recognized as American Scene Painting, which emerged after the American Regionalism movement, around the 1940s. American Scene Painting was then understood in two parts: the conservative painters who were anti-Modernists and the painters who resided in the countryside and voiced political, social, and economic issues while using themes of Nationalism and Romanticism to do so.

The abstract artists, on the other hand, reside mostly in urban areas and focused on life in American cities, as well as farmlands and local areas to drive political themes related to pre-industrialization.

The Regionalism Debate: Criticism

In learning more about the American Regionalism movement, it is also useful to consider the many criticisms it has received since the 1940s. Many critics have argued that the focus of American Regionalism neglected the diverse cultural experiences of those in urban environments and led to the incomplete depiction of American society in the 1930s. Additionally, other critics argued that American regionalist artists idealized the simplicity of rural life and its romanticization did not fully explore the challenges and complexities of living in rural America.

Another point worth noting is that, although there may have been representations of minorities created by predominantly white American artists, there was a lack of diversity since the view of America is skewed from an American regionalist point of view. Critics believed that American Regionalism artists resisted Modern art movements, which led to the ultimate downfall of the movement. Techniques within the movement were also underdeveloped due to the narrow range of themes explored. Furthermore, American Regionalism was a form of escapism from the challenges of pursuing an urbanized and industrialized life, which also undermined the value of artistic exchange among international art styles.

Critics such as Clement Greenberg also published texts that identified Realism, associated with American Regionalism, as kitsch and a tool of propaganda, which he described as “a debased… simulacra of genuine culture”.

The Influence of Regionalism on Contemporary Practice

How can American Regionalism, and Regionalism, be developed and improved in the digital age, and what influence does it have on the Contemporary period? Today, Regionalism can still be found in literature, advertisements, and movies, which provide a snapshot into the lived experiences of those from the Modern and Contemporary eras. Artists continue to embrace Regionalist themes, which have been seen in artists’ experience of a single location, which portray the domestic, spiritual, and social experiences of a place and time.

Artists also have access to digital tools such as social media, which enables a better approach to data visualization to get a holistic understanding of the infographics, influences, and regional statistics of a place to create informed artworks. Such digital tools can provide artists with valuable information, which artists back in the 1930s did not have access to, to reshape and develop the genre of Regionalism. Tools that enable digital Realism are worth exploring and include the creation of hyper-realistic images that employ 3D modeling and digital painting.

This offers new mediums through which one can explore Regionalist art, however, it is also important to recognize that digital tools and image generation programs are biased, which means that the data it relies on may not be accurate in terms of representing the real lived experiences of people in a particular region. Regionalists are also able to make use of augmented and virtual reality technologies to move Regionalist subjects off a two-dimensional place and into an immersive environment that simulates a regional experience and transcends geographic limitations.

American Regionalism was short-lived, yet it has left many lessons worth exploring so that you can improve your art practice. We hope that you have enjoyed learning about this 1930s art movement, and we encourage you to keep studying the works of influential figures.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is American Regionalism?

The 20th-century art movement known as the American Regionalism movement was the leading movement of the 1930s that focused on the depiction of the American Midwest. Themes expressed in the movement included small-town America and realistic and figurative scenes of agrarian life.

Who Are the Three Most Famous American Regionalist Painters?

The three most popular artists of the American Regionalism movement include Grant Wood, John Steuart Curry, and Thomas Hart Benton, who are regarded as the pioneers of American Regionalism.

What Is the Most Famous American Regionalist Artwork?

American Gothic (1930) by Grant Wood is considered to be the most famous American Regionalist artwork of the decade. The famous American Regionalist painting was a celebration of rural American values and a rejection of Modernism, as promoted by European art.

Jordan Anthony is a film photographer, curator, and arts writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. Anthony schooled in Durban and graduated from the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, with a Bachelor of Art in Fine Arts. During her studies, she explored additional electives in archaeology and psychology, while focusing on themes such as healing, identity, dreams, and intuitive creation in her Contemporary art practice. She has since worked and collaborated with various professionals in the local art industry, including the KZNSA Gallery in Durban (with Strauss & Co.), Turbine Art Fair (via overheard in the gallery), and the Wits Art Museum.

Anthony’s interests include subjects and themes related to philosophy, memory, and esotericism. Her personal photography archive traces her exploration of film through abstract manipulations of color, portraiture, candid photography, and urban landscapes. Her favorite art movements include Surrealism and Fluxus, as well as art produced by ancient civilizations. Anthony’s earliest encounters with art began in childhood with a book on Salvador Dalí and imagery from old recipe books, medical books, and religious literature. She also enjoys the allure of found objects, brown noise, and constellations.

Learn more about Jordan Anthony and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Jordan, Anthony, “American Regionalism – The Drive for Accessible American Art.” Art in Context. September 7, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/american-regionalism/

Anthony, J. (2023, 7 September). American Regionalism – The Drive for Accessible American Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/american-regionalism/

Anthony, Jordan. “American Regionalism – The Drive for Accessible American Art.” Art in Context, September 7, 2023. https://artincontext.org/american-regionalism/.