Norman Rockwell – Feel-Good Chronicler of American Life

Norman Rockwell the artist offered the world the defining image of everything it means to be “all-American.” Norman Rockwell’s famous paintings for The Saturday Evening Post are what he is mostly remembered for. Norman Rockwell’s illustrations revealed his fascination with the intricacies of the American nuclear family’s daily existence. This, combined with his essential participation in the World War II propaganda campaign, has earned him the rank of American legend.

Norman Rockwell the Artist

| Nationality | American |

| Date of Birth | 3 February 1894 |

| Date of Death | 8 November 1978 |

| Place of Birth | New York City |

Who is Norman Rockwell, and why is he such a highly regarded artist? He prefers to be considered a genre painter rather than just an illustrator, and he is most likely recognized for a specific sort of painting rather than individual works, and his image of the US small town has crept into the country’s collective psyche.

Even though his unrestrained national pride and visual aesthetic made him easy prey for left-wing academics, Norman Rockwell’s art from his later period displayed the impact of Social Realism.

Many of his mature pieces, particularly those he created for the Look publication, started taking on a far more socio-political stance. Norman Rockwell the artist’s contributions to the visual arts in America has properly been lauded by history, and his nostalgic pictures continue to grace diaries, postcards, banners, as well as other art paraphernalia.

A Biography of Norman Rockwell

Above everything else, Rockwell was a patriot. He was a pious and conventional thinker. His was a friendly and positive picture of the common American, and he portrayed the everyday routines and routines of the comely customs of classic American family life better than any other painter in its history.

Though he was ignored as an artist by some, Rockwell produced his compositions with wit and reverence for his subjects, as well as a precision that made the viewer “want to sigh and grin at the same time.”

Painting during a period when abstract painting was quickly gaining some popularity, Rockwell was adamant that his positive and straightforward pictures were superior to the self-indulgences of abstraction exploration.

Childhood and Education

Jarvis Rockwell, the supervisor of a Philadelphia textile business, and Anne Mary Rockwell, an apprehensive yet adventurous housewife, gave birth to Norman Rockwell. Throughout the summer, the family resided on country farms in New England. In his book, Rockwell claimed, “I have no terrible recollections of my summertime in the country; they had much to do with what I produced later on.” Even as a child, he admired the farm people’s open expressiveness and relished the tranquility of milking the cows, which compared with his hectic city existence.

Norman Rockwell liked sketching from a young age, so his father used to often sit with them drawing with him and Jerry, his brother, at the home dining table many times.

Primary school classes, on the other hand, made little sense to Rockwell, even though the school promoted sketching and coloring. Nevertheless, when Norman was approximately 8 years of age, his father started to read Charles Dickens’s works to the boys, and Norman was captivated. “I began to look at myself and to look at the situation the way I believed Dickens would have viewed them,” he later observed.

Norman’s grandmother died when he was just eight years old, and he and his family relocated to Manhattan to go and stay with his grandfather. Norman lacked the physical prowess of other boys his age, and athletic activities were valued in New York City schools at the time. He tried weight training but was unable to cure his awkwardness and pigeon-toed walk.

He subsequently commented on his predicament: “All I had was the skill to sketch, which didn’t seem to count for anything. But I started to devote my entire life to it. My emotions no longer held me back.” However, the young Norman still thought he fell short of the ideal American boy, with having “Perceval” as a middle name just adding to his concerns.

Early Training

Norman’s extended family had relocated from New York City to Mamaroneck, New York by the time he was a teenager. Their new house was in a nice, tranquil hamlet on the Atlantic Ocean, close enough to hear the waves lap. His church and school lives became less arduous and more pleasant. Rockwell started to make friends along the way with whom he developed a strong relationship.

Rockwell, now that he was mature enough to understand his family’s financial concerns, decided to start mowing lawns, buying a postal delivery route to the village’s richer section, and teaching. He taught mathematics, drawing, and painting to various students, including Ethel Barrymore.

Norman began attending art studies at The Chase School of Art when he was 14 years old, where he received his first training in art history, learning about John Singer Sargent and James McNeill Whistler.

Within a couple of years, he became even more certain of his desire to pursue his love, and he dropped out of high school to attend the National Academy of Design on his own dime. Rockwell was prepped for early commercial assignments by Fogarty, who specialized in illustration. Bridgman, on the other hand, provided him with additional technological expertise for life study. Rockwell’s first professional contract came from Fogarty, who arranged for him to create twelve “Tell-Me-Why” tales, which were prototype parent-child participatory children’s books.

He acquired a workspace in Brooklyn Heights beside the Brooklyn Bridge that was spacious enough to occupy with one of his drawing professors, Ernest Blumenschein. He registered in one drawing course at the Art Students League. When Rockwell was 18 years old, Thomas Fogarty advised him to show his works to Edward Cave, who had just been given the task of establishing Boys’ Life magazine as a national publication.

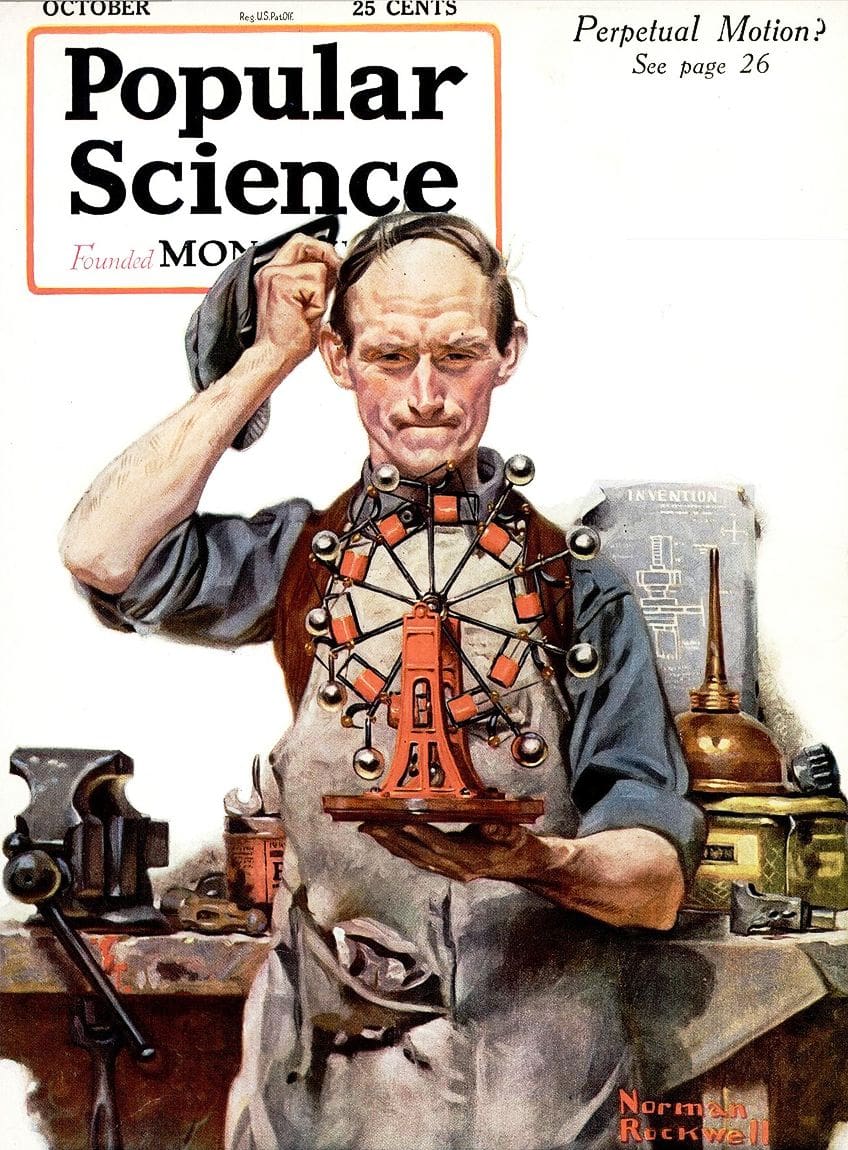

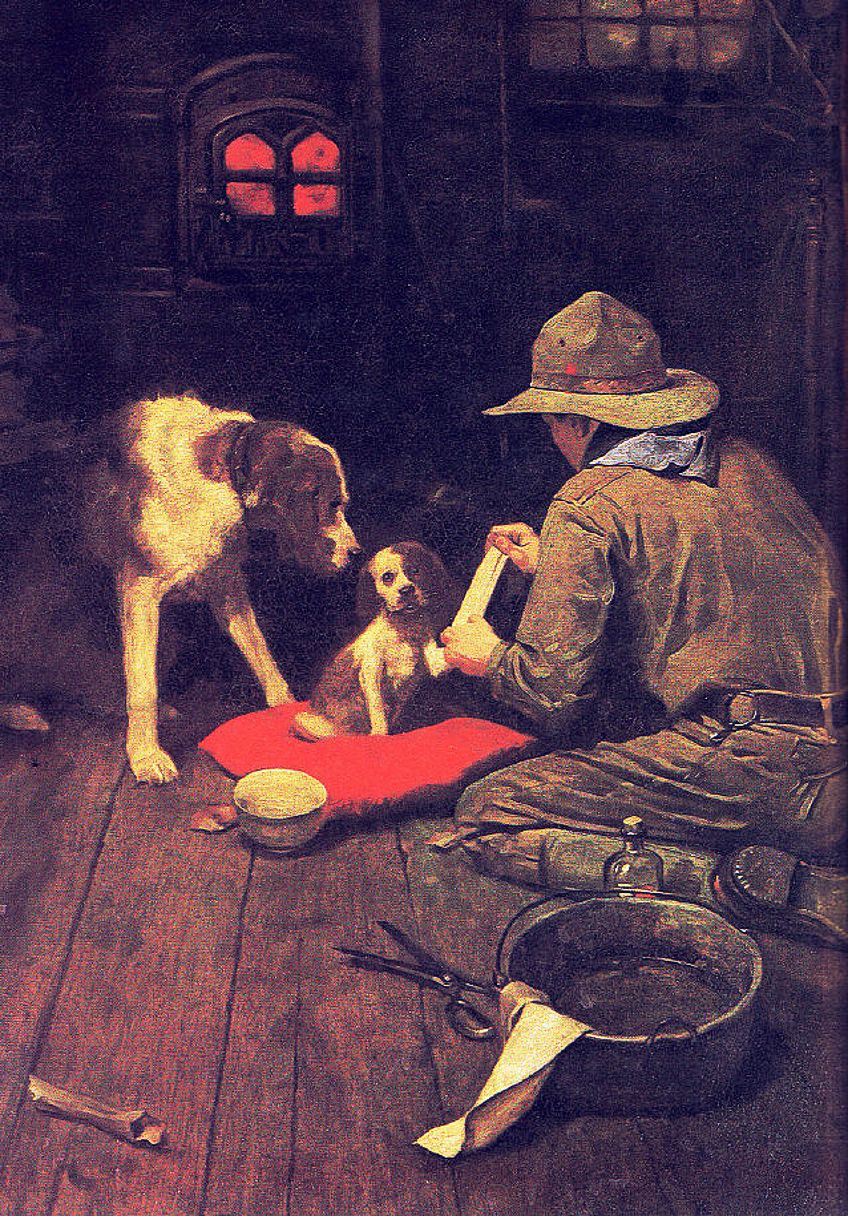

Cave offered Rockwell initial missions to establish himself: one was to make a camping handbook for the Boy Scouts, and the other was to maintain his submissions to Boys’ Life until he had done 400 drawings. At the age of 19, Rockwell was then asked to act as the art director for Boys’ Life, which was a periodical publication for the Boy Scouts of America.

At about the same period, Rockwell persuaded his family to relocate to New Rochelle, New York, a more refined environment that was home to numerous well-known painters, notably Joseph C. Leyendecker. He quickly made some good connections and got a new studio space. Rockwell met Clyde Victor Forsythe, a slightly older roommate and illustrator who also produced for “Boys’ Life”, in 1914.

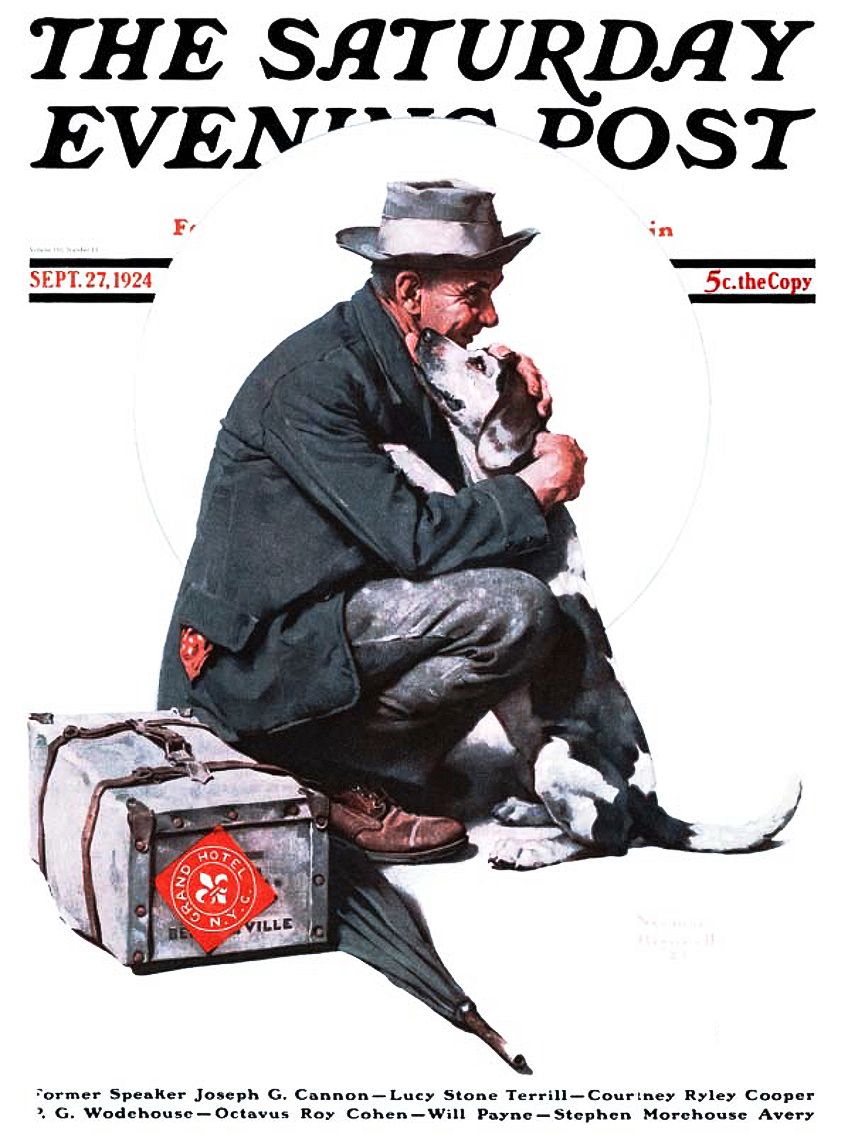

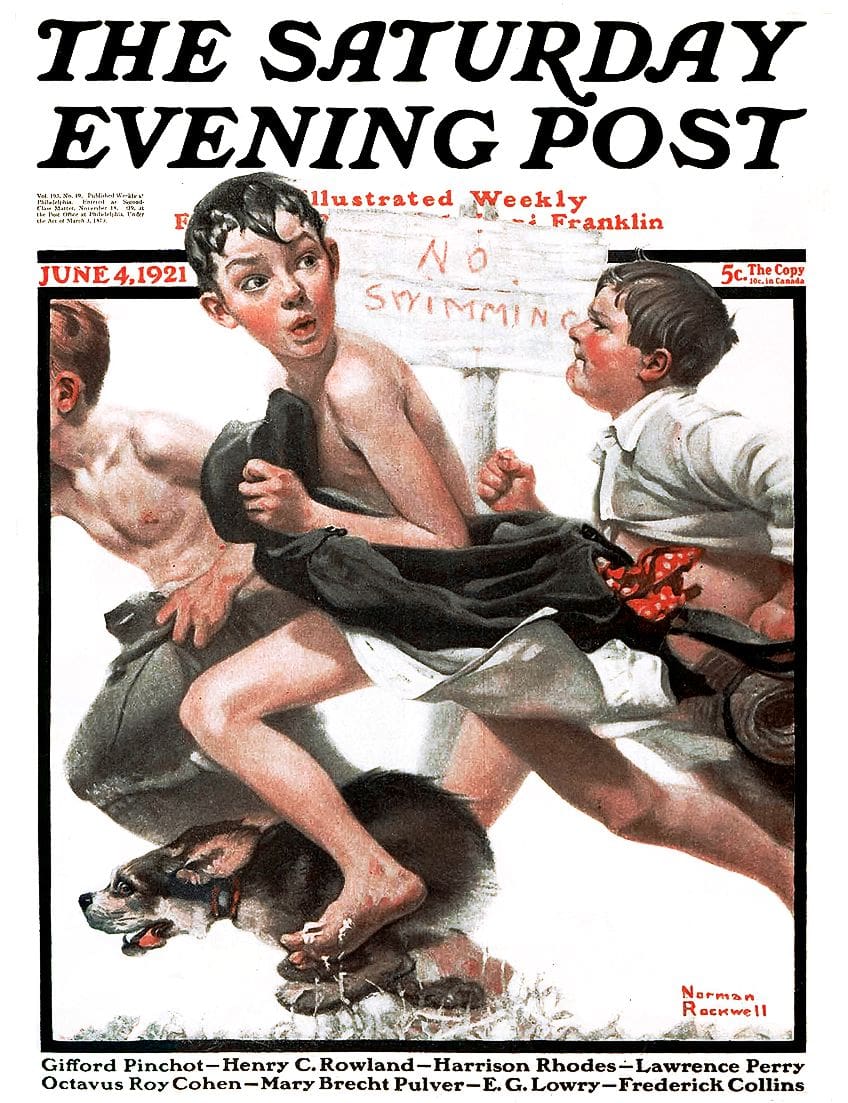

The more experienced artists had complete faith in Rockwell’s abilities and hired Frederic Remington’s derelict stable as their workshop. Forsythe encouraged his colleague to present his art to the Saturday Evening Post; in reality, Rockwell had frequently wished that his work would grace the cover of the popular magazine. Between the end of May in 1916 and the beginning of January 1917, six weekly editions of the publication featured Norman Rockwell’s paintings.

Meanwhile, in 1916, Rockwell encountered Irene O’Connor, a schoolteacher who accepted his hasty proposal. However, the marriage was difficult since Irene intended for him to have a normal work routine and desired his company at numerous social events.

Between the years 1916 and 1919, Norman Rockwell the artist produced 25 “Saturday Evening Post” covers as well as several story drawings. He’d already now become a national sensation, with “Life” magazine displaying him in a full-page advert for new memberships. “Life” was regarded by Rockwell to be the “biggest show window in America,” but his sudden success left the 25-year-old tired.

After a period of recuperation, Rockwell’s drawings began to display more artistic finesse than his early caricature-like figures by 1920. His new method appears to have replicated Bridgman’s life drawing teaching, and his new work earned him recognition among New Rochelle’s notable artists. He grew close to Leyendecker, whom he liked both professionally and personally.

While strolling around the village streets, Norman Rockwell would seek out the greatest models for each figure in his artwork. Clyde Forsythe, Rockwell’s friend, and studio mate noted that anytime his schedule became too hectic, he would take an unscheduled excursion but worried that his customers would abandon him.

Rockwell opted to study abroad in 1922, traveling to Paris for several weeks to join art school and explore galleries and museums. His brief visit brought him to southern France, Switzerland, and Italy. After returning to America, Rockwell painted numerous works on the topic of travel. One depicted a regular office worker engrossed in studying a postcard from overseas, while another depicted a little youngster admiring pictures from exotic locations. During the 1920s and 1930s, the topic of escape became a key component of his work.

Rockwell had painted the yearly cover for the customary Boy Scout Calendar for several years, but by 1924, he had become bored of it. However, after voicing his concerns to the publisher, they gave Rockwell a lucrative new deal. Rockwell opted to relocate out of his cramped house as a result of his newfound wealth.

Irene was hesitant to leave her family, so Rockwell relocated to a male-only painters’ society in Manhattan. The club, founded in 1880, has hosted celebrities such as Charles Hawthorne and Howard Pyle. Norman and Irene were soon reconciled and relocated to a freshly constructed home near New Rochelle. Rockwell was commissioned to create the Post’s first four-color cover art for the 6th of February, 1926 edition.

Rockwell thought he needed a vacation from his family life in August 1926 to devote all of his concentration to his painting. He moved to Louisville Landing to a cottage owned by Irene’s relatives, where he fished and painted in a nearby workshop. “There has never been a time of genius in the history of Norman Rockwell’s advancement,” said his friend Clyde Forsythe.

“Work is the answer! Work, work, and more work. Working in the workshop, working from home, reading excellent art and life books, pondering over concepts – studying – and more work.” Norman Rockwell’s art has become a regular presence, often gracing the covers of publications.

Yet, in the eyes of fine art experts, particularly Clement Greenberg, one of his sharpest detractors, Norman Rockwell’s paintings were excessively emotional, too commercialized, and plain folksy. Greenberg, the promoter of Abstract Expressionism, maintained that Rockwell was no more important than the lowliest artist.

Mature Period

Norman Rockwell and Irene opted to take split summer vacations in 1929, while on a family vacation in Louisville Landing. Rockwell traveled to Spain, Austria, and France with friends, seeing museums, hiking in the mountains, and sketching. However, upon his return, Irene, who had now fallen for a more stereotypical man, revealed her intention to divorce.

Despite being a womanizer himself, Rockwell was terribly sad and flew to California to seek help from Forsythe. While being in California, Forsythe presented Rockwell to Mary Barstow, a math teacher, and aspiring writer. The pair married on the 17th of April, 1930, at Mary’s parents’ lovely garden in Alhambra, Los Angeles, despite being 14 years apart in age.

In 1932, a worried Rockwell persuaded Mary to accompany him to Paris in the expectation that a shift of scenery might rekindle his dwindling vitality and confidence. Mary consented, and so the couple left with Jarvis, who at that time was only around 5 months of age.

Rockwell felt a surge of energy after boarding the ship, but while in Paris, the couple recognized that unless they returned home, Rockwell would struggle to find meaningful work to support his small family.

That September, the couple came to New Rochelle. Rockwell quickly discovered that he had been listed in Who’s Who in 1933. In 1935, Rockwell was approached with a new commission that ignited his creativity: George Macy wanted to commemorate the centennial of the birth of Mark Twain, by publishing updated editions of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn.

Rockwell chose to visit Hannibal, Missouri (the setting for Mark Twain’s writings) in order to acquire historical and geographical correctness. Rockwell documented his journey with photographs (a rather contentious method among “serious” painters at the time) and reviewed both books. Finally, for each book, Rockwell created eight color plates, which were released in 1936 and 1940, respectively.

Norman Rockwell and Mary relocated the family to Arlington in 1939. Arlington was a rural location with numerous farms, which matched their desires for a much more rural lifestyle in which to nurture three sons and Norman could paint in peace. The Rockwells were content with their move to Vermont, where they had made friends with the locals, participated in weekly square dances, and frequented monthly town hall meetings.

Late Period and Death

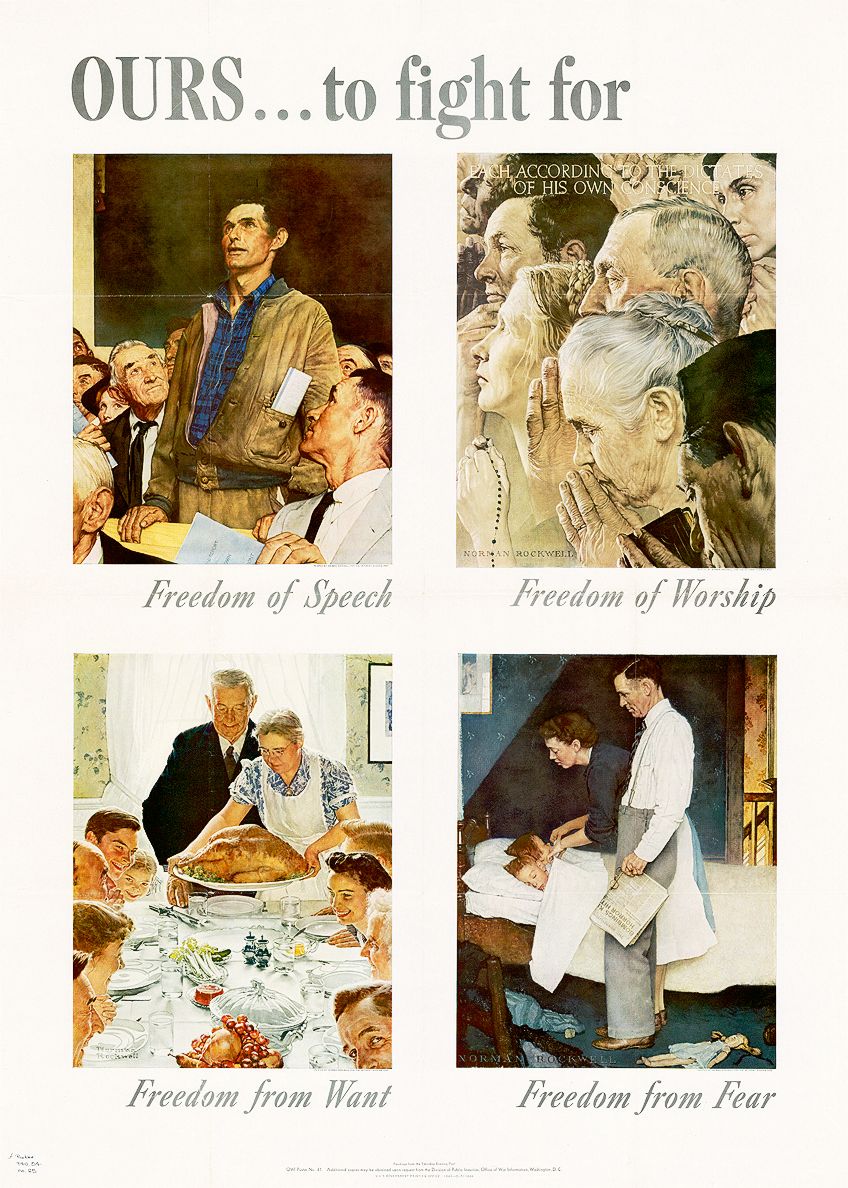

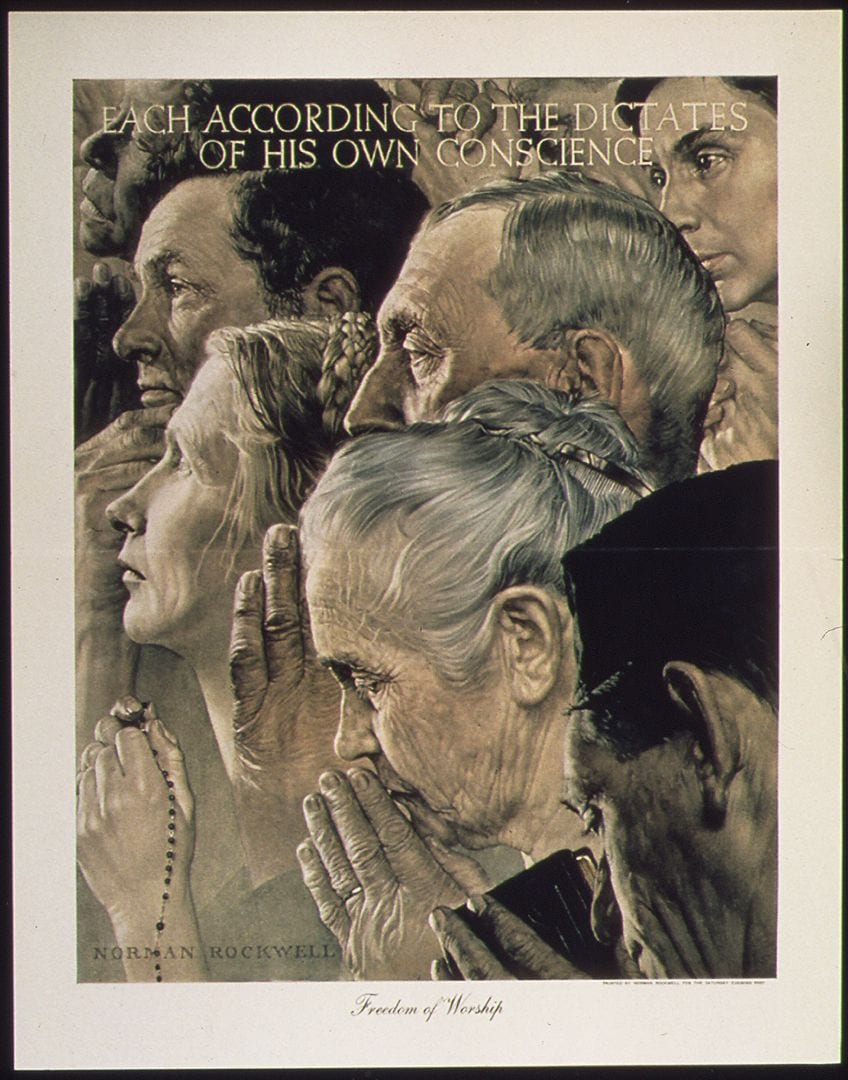

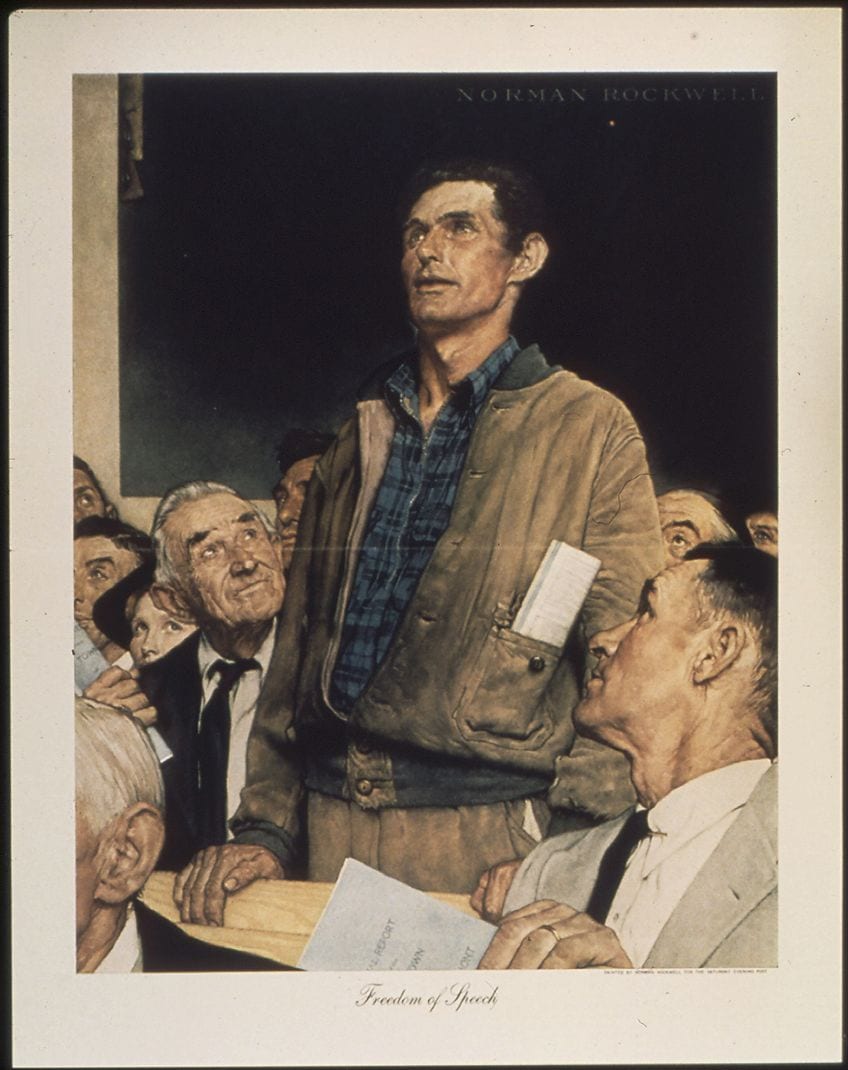

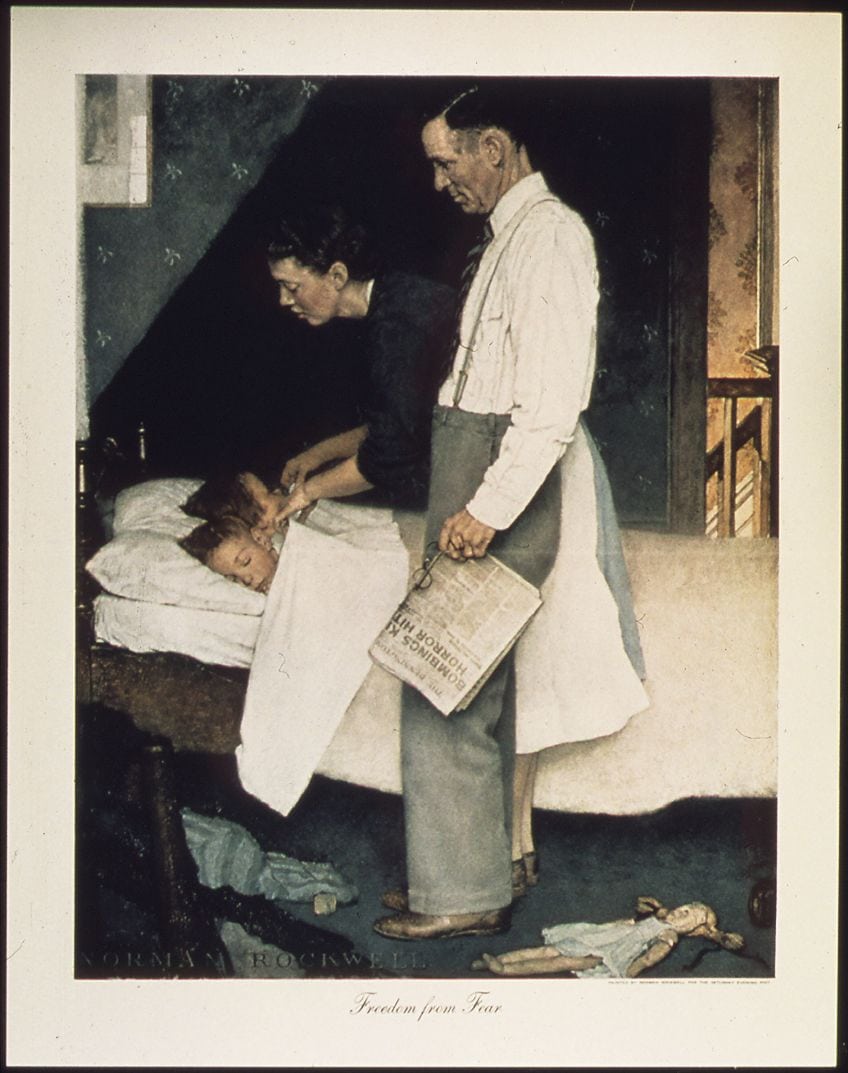

During the bombing of Pearl Harbour, Rockwell thought it was his obligation to create scenes that reminded Americans, particularly troops, that their independence and liberty were the most essential and valuable possessions they possessed. His main source of inspiration was President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s 1941 speech to Congress, which stated, “At no prior period has American safety been endangered from outside as it is presently.”

Rockwell produced his “Four Freedoms” images in 1943, which were reprinted in four editions of the Post, along with comments by contemporary writers. The sequence toured the United States, raising almost $130 million for the war effort. The Rockwells once again moved, this time to an old farmhouse in West Arlington at the conclusion of the war, when the artist transformed an old barn into a modern working studio, his former studio and all its furnishings having been burnt to the ground a year earlier.

The Rockwells spent the frigid winter of 1944 trekking and appreciating Vermont, but it was evident by the fall of 1948 that Mary had acquired a drinking problem. She was lonely and fatigued, and she was struggling to keep up with her responsibilities, particularly monitoring her husband’s bank documents. During 1952, Mary sought mental therapy at the private facility Austen Riggs, where she endured shock treatments.

Norman Rockwell had also agreed to treatment for his own anxieties and regular episodes of depression, and in December 1953, the Rockwells made the mutual decision to relocate to Stockbridge, Massachusetts, to be closer to the treatment facility and to experience the cultural and social benefits of living in a city.

By that spring, the Rockwells had relocated to a new home. Norman Rockwell the artist had a new workspace, so he and Mary started going to live model drawing lessons together. With all three sons attending private schools and the costs of their own health care growing, Rockwell needed to find a new source of income. In the summer of 1955, he returned to the Post and agreed to create portraits of Presidential contenders Dwight Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson. On the 25th of August, 1959, disaster struck when Mary died suddenly of heart failure aged 51.

Norman was deeply upset, and he became disoriented, confused, and despondent. Soon after, Rockwell met Molly Punderson, a lovely 62-year-old well-educated instructor. In October 1961, the pair married. That same year, he was ecstatic to find that he had been described as “part of a heritage of hilarious genre painters extending back at least to seventeenth-century Holland.”

His self-esteem skyrocketed after being recognized as a genre master rather than an ordinary illustrator. Norman Rockwell was eager to learn about Social Realism, while Molly was keen on learning about the Russian educational system.

Norman had sketched the schoolchildren on an earlier trip in 1964, and subsequently developed the piece Russian Schoolroom (1967) in a new photo-realist technique. The couple then traveled to Russia for the 1963 World Fair and subsequently on to Egypt, where Norman Rockwell produced a picture of the Egyptian President Nasser.

This would turn out to be his final cover for the Post, which was struggling financially. Molly and other Stockbridge women acquired a historic building the same year to establish a museum/historical society. Rockwell lent them several works, and the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge quickly became a viable cultural destination.

Molly also encouraged her husband to arrange his art collection and estate. He was encouraged to arrange his many paintings when a renowned Manhattan gallery approached him about hosting a display in the fall. In 1968, he had his first solo show at the Bernard Danenberg Gallery.

That November, Harry Abrams released Rockwell’s first significant biography. The revived appreciation in Norman Rockwell’s art throughout the 1970s reflected a broad rejection of abstract painting. To promote the book, Rockwell went on a promotional tour and appeared on various talk shows. By the autumn of 1971, he was absolutely tired once more.

He had been working through a particularly hot summer, and his August picture of Frank Sinatra revealed a decrease in his ability. The Danenberg Gallery organized a mobile exhibit which was titled “Norman Rockwell: A Sixty-Year Retrospective” in 1972. It toured across nine cities in two years. Even though critical judgment was varied, the audience was massive.

By the end of August 1973, Norman Rockwell was feeling ill enough to keep a calendar of his moments of mental exhaustion. Norman had a small stroke in 1974 when he was 80 years old.

“I knew he wasn’t really okay, he simply wasn’t always on beat, sometimes good, other times mysteriously off,” Molly said of her husband’s declining health. Rockwell’s color vision had also been affected by his cataracts, and he was unable to differentiate certain color ranges. Norman Rockwell died quietly in his own bed on the 8th of November, 1978.

Important Artworks

A conservatorship of his artworks and sketches was established with Rockwell’s aid at his house in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, and the Norman Rockwell Museum is currently open every day around the year. Below are a few examples of his most renowned pieces.

More than 700 of Norman Rockwell’s illustrations, sketches, and studies may be found in the Norman Rockwell museum’s collection.

- Santa and Scouts in Snow (1913)

- Boy with Baby Carriage (1916; first Saturday Evening Post cover)

- Circus Barker and Strongman (1916)

- Gramps at the Plate (1916)

- Redhead Loves Hatty Perkins (1916)

- People in a Theatre Balcony (1916)

- Tain’t You (1917; first Life magazine cover)

- Cousin Reginald Goes to the Country (1917; first Country Gentleman cover)

- Santa and Expense Book (1920)

- Mother Tucking Children into Bed (1921; first wife Irene as the model)

- No Swimming (1921)

- Santa with Elves (1922)

- The Love Song (1926, Ladies Home Journal)

- Doctor and Doll (1929)

- Deadline (1938)

Norman Rockwell’s Art Style and Legacy

Norman Rockwell’s impact on American art has been subjected to justified revision, despite being praised by the likes of satirist George Grosz, and Willem de Kooning who lauded Norman Rockwell’s illustrations for their “incredible skill, clarity of touch,” and a populist intuition that was “so ubiquitous that he would be praised everywhere.”

Norman Rockwell’s art had “much greater lasting power than that of innumerable abstract painters who were lauded in his lifetime,” according to his biographer Deborah Solomon. Sure, Norman Rockwell’s paintings are realistic and romantic, but they provide the truest depiction of what it was like to be an American in the 20th century – always a fictitious state.

His photos, which are still mass copied, are considered now almost as paeans for a bygone era, according to The New York Times, which once stated that his work was on par with Mark Twain’s books in terms of importance to America’s self-image.

Meanwhile, his pictures of suburban America from the 1920s through the 1950s have served as inspiration for filmmakers like Steven Spielberg, George Lucas, and Robert Zemeckis, whose Oscar-winning 1994 film “Forrest Gump” pays homage to Rockwell by replicating many of his canvases as scenes.

The Norman Rockwell Museum is dedicated to spreading “the capacity of visual imagery to change and reflect society” and has the world’s biggest collection of his work. “The Museum encourages social good via civic ideals of learning, respect, and inclusiveness, and is devoted to preserving freedom and respect through the timeless messages of compassion and generosity expressed by Norman Rockwell,” the museum’s mission statement states.

During his lifetime, professional art reviewers disregarded Rockwell’s work. In the eyes of current critics, many of his works, particularly the Saturday Evening Post covers, which trend toward utopian or sentimentalized depictions of American life, are too sweet. The word “Rockwellesque” was coined as a result of this. As a result, some modern artists perceive

Norman Rockwell the artist was prolific and created over 4,000 unique pieces during his career. The majority of his paintings are housed in public collections. In addition to painting portraiture for Presidents Kennedy, Eisenhower, Johnson, and Nixon, as well as international luminaries like Jawaharlal Nehru and Gamal Abdel Nasser, Norman Rockwell was contracted to illustrate more than 40 novels, including “Tom Sawyer” and “Huckleberry Finn.”

Rockwell’s work is often seen as kitsch, with other artists not considering him a “serious painter.” Some reviewers refer to him as an “illustrator” rather than an artist, which he didn’t mind because that’s what he identified himself with.

However, in his later years as an artist, when he picked more serious topics, such as the racist sequence for “Look” magazine, Rockwell began to gain more notice as a painter. “The Problem We All Live With”, which covered the ever-present topic of racial integration in schools, is an example of this more significant work.

The sequence recounts the story of Ruby Bridges, a young black girl, who was escorted by white federal marshals while she walked to school past a wall vandalized by racist graffiti. When Bridges visited with President Barack Obama in 2011, this 1964 artwork was on exhibit there.

Recommended Reading

If you enjoyed this Biography of Norman Rockwell, you might be interested in learning more about him. Therefore, we have compiled a few books that will educate you further about Norman Rockwell the artist. With these books, you can discover more about Norman Rockwell’s paintings in your own time!

My Adventures as an Illustrator (2019) by Norman Rockwell

Norman Rockwell the artist’s humor, empathy, and multifaceted talent are on full show in his famous autobiography. Rockwell’s early years in New York City, his days as an apprentice at the Art Students League, his fatal first visit to the Saturday Evening Post, his travels overseas, and his transfer to rural Vermont are all told with a blend of acute observation and self-deprecating humor. Throughout the book, Rockwell takes the reader into his creative process by introducing his favorite models, frankly revealing his worst flops, and meticulously documenting the development of a Post cover.

- Chronicles the life of America's most beloved artist in his own words

- Illustrates more than 150 of Rockwell’s paintings and drawings

- Includes restored text and drawings, new illustrations, and more

American Chronicles: The Art of Norman Rockwell (2015) by Norman Rockwell

A superb artist depicts American life in a witty and satirical manner. Norman Rockwell, one of the most well-known American painters of the 20th century, was sometimes dismissed as a basic illustrator, with his work associated with Saturday Evening Post covers. Instead, he is a complete artist. Rockwell, a keen investigator of human nature and a gifted storyteller portrayed America’s changing culture in little details and subtleties, depicting scenes of regular people’s daily lives and providing a particular and often romanticized version of American identity. In an era of epoch-making transition that led to the development of modern American society, his images provided a soothing visual sanctuary.

- The exhibition catalog presents well-known and beloved masterpieces

- Includes Rockwell's carefully observed images of youthful innocence

- Beautifully reproduced photographs of Rockwell's artworks

In the mid-20th century, Norman Rockwell was a well-known American painter. Norman Rockwell’s art, most known for his commercial drawings, frequently represented American society. The artist Norman Rockwell gave the world the definitive image of what it means to be “all-American.” Norman Rockwell is best renowned for his drawings for The Saturday Evening Post. Norman Rockwell’s paintings reflected his preoccupation with the complexities of the daily lives of American nuclear families. This, together with his pivotal role in the propaganda effort during World War II, has elevated him to the status of American mythology.

Take a look at our Norman Rockwell paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Is Norman Rockwell?

His portrayal of the typical American was warm and upbeat, and he captured the regular routines and comely rituals of traditional American family life better than any other painter in the country’s history. Rockwell’s compositions were filled with wit and regard for his subjects, as well as a precision that made the spectator want to sigh and laugh at the same time, according to some. Painting during a time when abstract painting was becoming more fashionable, Rockwell was sure that his cheerful, uncomplicated images were superior to abstraction exploration’s self-indulgence.

What Was Norman Rockwell Known For?

Norman Rockwell, among the most renowned American artists of the 20th century, was sometimes regarded as a simple illustrator, his work being connected with Saturday Evening Post covers. Rockwell, a talented storyteller and astute observer of human nature, depicted America’s developing culture in little details and nuances, presenting scenes of ordinary people’s daily lives and offering a distinct and sometimes idealized interpretation of American identity. His images provided a relaxing visual refuge at an era of epoch-making transition that contributed to the development of contemporary American society.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Norman Rockwell – Feel-Good Chronicler of American Life.” Art in Context. March 7, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/norman-rockwell/

Meyer, I. (2022, 7 March). Norman Rockwell – Feel-Good Chronicler of American Life. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/norman-rockwell/

Meyer, Isabella. “Norman Rockwell – Feel-Good Chronicler of American Life.” Art in Context, March 7, 2022. https://artincontext.org/norman-rockwell/.