Edward Hopper – An Introductory Edward Hopper Biography

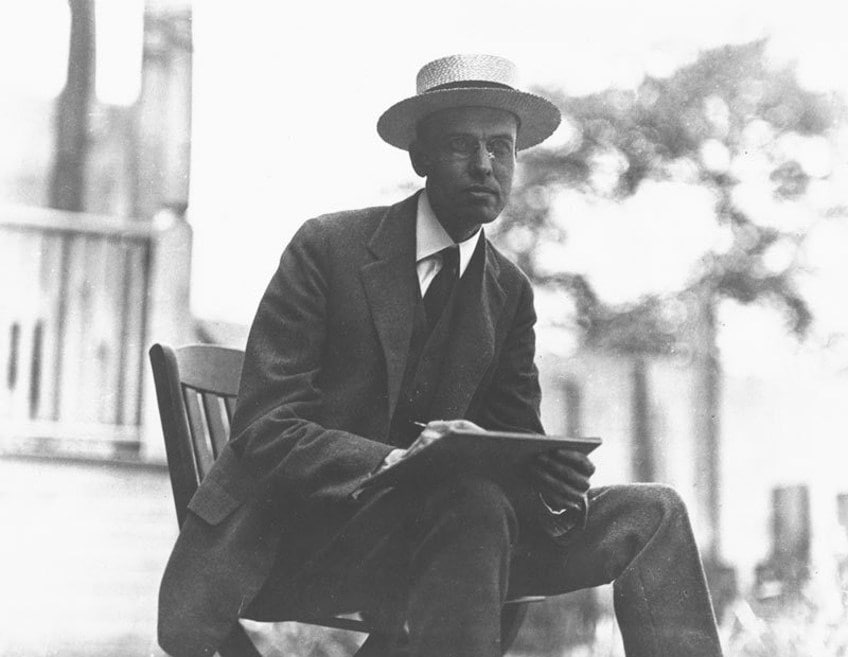

Edward Hopper was a native of Nyack in New York and was born on the 22nd of July in 1882. Hopper the artist was highly renowned for his Realist style oil artworks, yet he was also a very capable etch printmaker and watercolorist. Edward Hopper’s paintings were noted for their depictions of everyday situations which were subtly layered with drama and metaphor, which sparked many variations in interpretation, which was often not the artist’s intention.

Edward Hopper’s Biography

Before we can gain insight into Edward Hopper’s artworks and the influence of Hopper the artist, we first need to understand the story of Hopper the man. We will start with the early childhood life of the artist and then discover the key moments that lead to the rise of his popularity and admiration by exploring Edward Hopper’s biography.

Edward Hopper’s Early Life

North of the city of New York runs the Hudson River, and it is on the banks of the river that we find Nyack, a small village known mostly for its yacht building industry. Hopper was born to Elizabeth and Garret Hooper in 1882 and was one of two siblings. The two children were raised in a disciplined religious environment, and the household was a matriarchy, with the home run by the four women, including mother, sister, grandmother, and even the maid, as his father was a rather mild character who did not assert much dominance on the family.

Edward Hopper was an outstanding scholar at the elementary level and a superb illustrator when he was only five years old. He quickly adopted his father’s academic inclinations as well as his appreciation of Russian and French traditions.

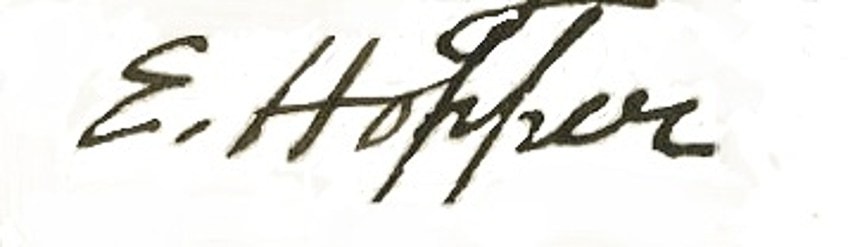

He also exhibited his mother’s creative talent. Hopper’s family supported his artistry and equipped him with a wealth of resources, instructive periodicals, and graphic literature. At the age of ten, he started to sign and date his artwork. The oldest Edward Hopper drawings are sketches of geometric shapes using charcoal such as a pitcher, bowl, mug, and containers. The careful investigation of shading and lighting that would endure for the duration of his life can be recognized in these earliest drawings.

By the time he reached adolescence, he was producing with pen-and-ink, charcoal, watercolor, and oil, sketching from the environment and creating political satire.

Rowboat in Rocky Cove, his first signature oil painting, was completed in 1895 after he duplicated it from a print in The Art Interchange, a prominent periodical for novice painters. Other early oil Edward Hopper paintings, such as Ships (1898), have been recognized as reproductions of works by painters such as Edward Moran and Bruce Crane.

In his early self-portraits, Hopper portrayed himself as thin, unkempt, and unattractive. Though he was a tall and introverted adolescent, his keen sense of humor found expression in his work, usually in representations of foreigners or females overpowering men in funny circumstances. Later in life, he primarily portrayed ladies in his works. He aspired to be a naval architect in high school, but after graduating he proclaimed his decision to pursue an art profession. Hopper’s family pushed that he pursue commercial art in order to have a steady source of revenue.

Ralph Waldo Emerson’s ideas inspired Hopper in establishing his self-image and independent life philosophy.

In 1899, Hopper began his painting education with a mail program. He soon relocated to the school of Art and Design in New York. He studied for six years there, with professors like William Merritt Chase, who taught him oil painting. Hopper’s early approach was influenced by his professor as well as French Impressionist artists like Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet.

Drawing from live models was difficult and surprising for the religiously reared Hopper. Life class was given by artist Robert Henri, another of his professors. Henri pushed his pupils to “create a commotion in the world” through their work. “It isn’t the topic that matters, but how you are feeling about it,” he told his pupils, and “Ignore art and create images of what fascinates you in life.” In this way, Henri inspired Hopper and urged him to infuse his art with a contemporary attitude.

During his college years, he also produced scores of naked paintings, still life works, panoramas, and portraiture, including self-portraits.

Hopper found part-time work with a marketing firm, where he designed industry periodical covers in 1905. Hopper grew to dislike illustration. Until the mid-1920s, he was forced to do so for financial reasons. He briefly fled by traveling to Europe three times, each time to Paris, reportedly to study the artistic community there.

In reality, he worked alone and appeared largely untouched by new artistic tides. Afterward, he stated that he “didn’t recall ever hearing about Picasso.” He was a big fan of Rembrandt, especially his The Nightwatch (1642), which he described as “the most amazing thing” he had ever witnessed – “it’s beyond comprehension in its realism.”

Hopper initially worked with a dark color palette, creating urban and architectural themes. Then he switched to the brighter palette of the Impressionists before reverting to his preferred darker palette. “I got over it, and later works produced in Paris were far more the type of stuff I make now,” Hopper later remarked.

Hopper devoted a lot of time painting street and bistro scenes, as well as traveling to the opera and the theater.

Unlike many of his peers, Hopper was drawn to realist painting rather than abstract cubist attempts. Later, he acknowledged having no European inspirations other than French engraver Charles Meryon, whose melancholy Paris landscapes he copied.

Period of Hardship

Hopper hired a workspace in New York City after arriving from his most recent European tour, where he battled to establish his own manner. To sustain himself, he grudgingly resorted to drawing. As a freelancer, he was obliged to pitch for assignments and call on the doors of publication and firm offices in order to obtain work.

His artwork was dormant: “It’s difficult for me to determine what to create. Occasionally I spent months without uncovering it. It takes time.”

Edward Hopper went to Massachusetts in 1912, in search of ideas, and created his first landscape works in the United States. Squam Light was the first of several lighthouse images he created. Hopper received $250 in 1913 at the Armory Show for his debut work, Sailing (1911), which he had repainted over an older self-portrait.

Hopper was 31 years old, and while he anticipated that his first transaction would progress to others in the near future, his profession would not take off for several years. He proceeded to take part in group exhibits at modest locations, such as New York’s MacDowell Club. The next year, he was hired to design cinema posters and oversee PR for the film business. While he disliked illustration, Hopper was a passionate fan of the film and the theater, which he used as topics for his works. His composing approaches were inspired by each form.

By 1915, Edward Hopper’s artwork had reached a stalemate, and thus began the production of Edward Hopper’s prints.

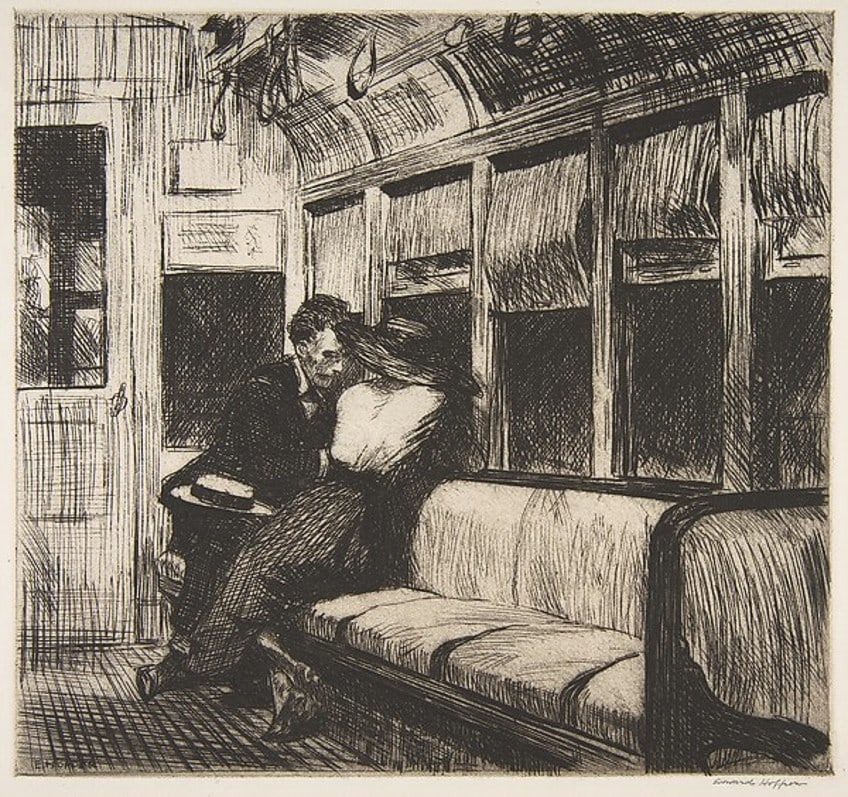

In 1915, after reaching a stalemate with his oil paintings, Hopper resorted to etching. By 1923, he had completed the majority of his around 70 works in this format, many of which depicted metropolitan views from both New York And Paris. He also created several banners for the military effort while still managing to work on rare commercial assignments. On trips to New England, Hopper painted some outside oil paintings when time permitted, particularly at the art colony at Monhegan Island. Edwards Hopper’s prints started to gain popular recognition during the early 1920s.

Many similar themes that can be observed in his later work are also evident here, such as the depiction of silent couples (Night on the El Train), basic maritime scenes (The Catboat), and portrayals of a solitary woman as can be observed in Evening Wind. Despite these being hard years for the artist, he did begin to gain some recognition for his work, such as being awarded a prize in 1918 for his poster created for the war entitled Smash the Hun.

Around this time he also began to display his artworks at exhibitions such as one with the Society of Independent Artists in 1917 and two at the Whitney Studio Club in 1920 and again in 1922.

Edward Hopper’s Artwork Breaks Through

By 1923, Hopper the artist’s steady ascent had resulted in a breakthrough. In a summer art excursion in Massachusetts, he came across Josephine Nivison, a painter and previous pupil of Robert Henri. He was towering, cautious, timid, introverted, contemplative, and traditional, whereas she was small, extroverted, sociable, outgoing, and progressive. A year later, they were wed.

“Often, chatting to Eddie is like dumping a pebble in a well, only it doesn’t pound when it strikes the bottom,” she observed.

She deferred her profession to his and adopted his secluded habits. The remainder of their life centered around their modest home in the metropolis and their vacations on Cape Cod’s South Truro. She oversaw his business and appearances, served as his major role model, and was his lifelong partner.

Six of Edward Hopper’s paintings from Massachusetts were accepted to an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 1923 thanks to Nivison’s assistance. One of these, The Mansard Roof, was acquired for $100 by the museum for its permanent inventory. His work was lauded by critics in general; one said, “What vigor, power, and forthrightness! Consider what can be done with the most mundane issue.”

The next year, Hopper auctioned all of his watercolors in a one-man exhibition and chose to retire from illustration. Hopper earned more acclaim for his art when he was 41 years old. He remained resentful about his profession, later declining appearances and prizes.

With his financial security ensured by consistent sales, Hopper was able to live a modest, stable existence while continuing to create work in his own unique way for the next four decades.

During the Great Depression, Hopper did better than many other painters. His popularity skyrocketed in 1931 when prominent institutions such as the Whitney Museum of American Art offered thousands of dollars for his paintings. The Hoppers leased a home in South Truro, Cape Cod, in 1930. They visited every summer for the remainder of their lives, eventually erecting a summer home there in 1934.

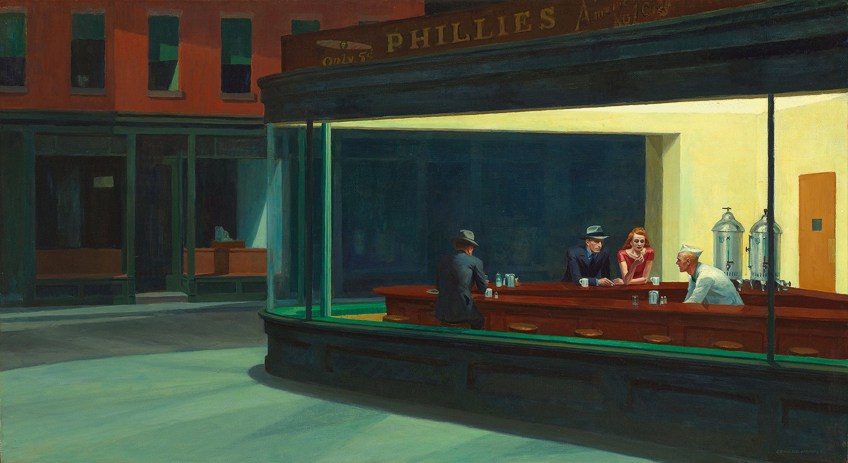

Throughout the 1930s and early 1940s, Hopper was extremely active, releasing several notable works such as Girlie Show (1941), and Nighthawks (1943). On the 15th of May, 1967, Hopper passed away of natural causes in his workshop in New York City.

Edward Hopper Artworks and Style

We have now covered the very early days of Edward Hopper’s drawings as a child, as well as the initial developmental stages of Edward Hopper’s prints, oil paintings, and watercolors. Now we will take a deeper look into Edward Hopper’s artworks and style.

We will take a look at the vision and character of Edward Hopper’s paintings, the methods he used, the themes he explored, and the influence of his artwork.

Edward Hopper’s Vision and Character

Hopper, who was always hesitant to describe himself or his art, simply stated, “The full explanation is there in the painting.” Hopper was a stern and nihilistic man with a mild sense of humor and a straightforward demeanor. Hopper was driven to anti-narrative metaphor and “created brief solitary moments of arrangement, loaded with insinuation.” His uncomfortable interactions and silent settings “strike us where we are most susceptible,” with “a hint of sorrow, that sadness being portrayed.”

As he “transformed the Puritan into the purest, in his calm paintings where flaws and graces harmonize,” his understanding of color showed him as a pristine artist.

He was an authentically local artist who, more than anyone else, was capturing the character of America on canvas. Traditional in politics and current events (for example, Hopper claimed that “artists’ biographies should be dictated by those very near to them”), he tolerated matters as they were and lacked idealism. He was well-read and educated, and many of his works depict individuals reading. He was typically pleasant company and unbothered by periods of silence, yet he might be sullen, irritable, or distant at times.

He was very sincere about his work and the artwork of others, and when questioned, he would provide his honest view.

In a statement submitted to Reality, an art publication in 1953, Hopper wrote: “Great art is the outer manifestation of the artist’s inner existence, which results in his personal perspective of the world. No degree of inventiveness, no matter how skilled, can supplant the crucial element of creativity. One of the flaws of much abstract art is the effort to replace human intelligence innovations with a private creative notion. The interior life of a person is a wide and diversified domain that is concerned with more than just exciting combinations of hue, shape, and form. The phrase ‘life’ in art should not be dismissed, because it entails all of life, and the domain of art is to respond to it rather than to avoid it.”

Hopper’s Artistic Methods

Although he is most known for his oil paintings, Hopper first gained popularity with his watercolors, and he also made several commercially lucrative etchings. His journals also include high-quality pencil and pen drawings that were never intended for public access. Hopper was especially concerned with geometrical designs and the meticulous arrangement of human forms in appropriate proportion with their surroundings.

He was a systematic and patient artist; as he stated, “A concept takes a long time to develop. Then I have to ponder about it for a long period of time. I don’t start working until I have everything planned out in my head. I’ll be fine when I get to the canvas.”

Hopper’s approaches rely heavily on the efficient use of shading to create a mood. Bright sunshine (as a sign of enlightenment or illumination) and the shadows it produces also play allegorical significance in Edward Hopper paintings such as Summertime (1943), Sun in an Empty Room (1948), and Second-Story Sunlight (1960). His utilization of highlights and shadows has been likened to film noir lighting. Hopper was a realist artist, but his “soft” realism reduced forms and nuances. He employed vivid colors to create atmosphere and intensity.

Themes and Subject Matter

Hopper drew inspiration for his subjects from two major sources: one, ubiquitous aspects of Modern America (service stations, lodges, cafés, theaters, railways, and streetscapes) and their people, and the other, seascapes and countryside. In terms of his own style, Hopper described himself as “a mixture of various cultures” who was not a student of any method, notably the “Ashcan School.” Despite the various art fads that came and went over Hopper’s lengthy career, his painting remained constant and self-contained.

Hopper’s seascapes are divided into three categories: pure vistas with cliffs, ocean, and beachfront grasses; beacons and country houses; and boats.

He occasionally mixed these components. The majority of these paintings feature bright light and pleasant weather; he was uninterested in winter or rain landscapes, or periodic changes in color. Hopper was equally interested in urban architecture and cityscapes.

“Our national design with its terrible grandeur, its weird rooftops, pseudo-gothic, Franco Mansard, Imperial, hybrid or whatever else, with eye-searing hue or subtle harmonies of fading paint, carrying one another down unending avenues that fall off into marshes or trash heaps,” he said.

He created House by the Railroad in 1925. This famous painting portrays a solitary Victorian wood home, partially hidden by a railway barrier. It was a watershed moment in Hopper’s creative development. Lloyd Goodrich called the picture “one of the most heartbreaking and depressing works of realism.”

The piece is the first in a sequence of the harsh countryside and metropolitan images that employ sharp lines and big forms, accentuated by strange lighting, to portray his subjects’ solitary atmosphere. Despite the fact that critics and spectators discern meaning and emotion in these urban landscapes, Hopper claimed, “I was more concerned in the sunshine on the architecture and on the persons than any significance.”

The majority of Hopper’s figure paintings center on the delicate interplay of humans with their surroundings, whether done with single individuals, pairs, or groups. His main emotional motifs include isolation, loneliness, remorse, tedium, and surrender. He communicates his feelings in a variety of settings, including the workplace, public locations, residences, on the road, and on holiday.

Hopper framed his figures as though they were taken just before or immediately after the culmination of a drama as if he were making screenshots for a film or vignettes in a drama.

Cape Cod Evening (1939) is one of his “couple” artworks. In the first, a youthful couple appears estranged and unsociable, with him perusing the newspaper and her idling by the piano. The spectator assumes the position of a voyeur, peering through the apartment window using a telescope to observe the pair’s lack of connection. In the second image, an older couple who have little to say to one another is interacting with their pet, whose focus is diverted away from its owners. With Excursion into Philosophy, Hopper takes the relationship concept to a new level. A middle-aged man slumps on the side of a bed, despondent.

Edward Hopper’s Position in American Art

Hopper used a kind of realism acquired by another famous American realist, Andrew Wyeth, in focusing largely on calm moments and very rarely portraying movement, but Hopper’s approach was entirely different from Wyeth’s hyper-detailed manner. Hopper collaborated with some of his peers, like George Bellows and John Sloan, but eschewed their blatant movement and brutality.

Whereas Georgia O’Keeffe and Joseph Stella romanticized the city’s gigantic architecture, Hopper stripped them to commonplace geometrics, and he portrayed the city’s rhythm as bleak and hazardous instead of “beautiful or alluring.”

“He accomplishes such a perfect verity that you may interpret into his renditions of homes and ideas of New York life any humanistic connotations you choose,” remarked Charles Burchfield, whom Hopper adored and to whom he was likened. He also credited Hopper’s popularity to his “strong individuality; in him, we have recovered that robust American autonomy which Thomas Eakins gave us, but which we had lost for a time.” Hopper saw this as high praise since he believed Eakins to be the finest American artist.

According to Deborah Lyons, “Our personal epiphanies are frequently echoed, transcendentally, in his art. Once viewed, Hopper’s perceptions coexist with our own reality in our awareness. We will always recognize a specific style of building as a Hopper building, maybe imbued with a mystique that Hopper placed in our own imagination.” Edward Hopper’s artworks bring to light the apparently commonplace and routine events of our daily lives, giving them new meaning.

In this way, Hopper’s work transforms the harsh American terrain and solitary petrol stations into a feeling of exquisite expectation.

Exhibitions of Edward Hopper’s Prints and paintings

- Edward Hopper: The Art and the Artist debuted at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1980 and traveled to Amsterdam, Düsseldorf, and London, as well as Chicago and San Francisco. This exhibition included his oil paintings along with preliminary Edward Hopper drawings for the first time. This marked the start of Hopper’s fame in Europe and his international renown.

- A major collection of Hopper’s paintings were taken around Europe in 2004, including stops at the Tate Modern in London and the Museum Ludwig in Cologne, Germany, having 420,000 attendees in the three months it was accessible; the Tate exhibit became the gallery’s second-biggest in its history.

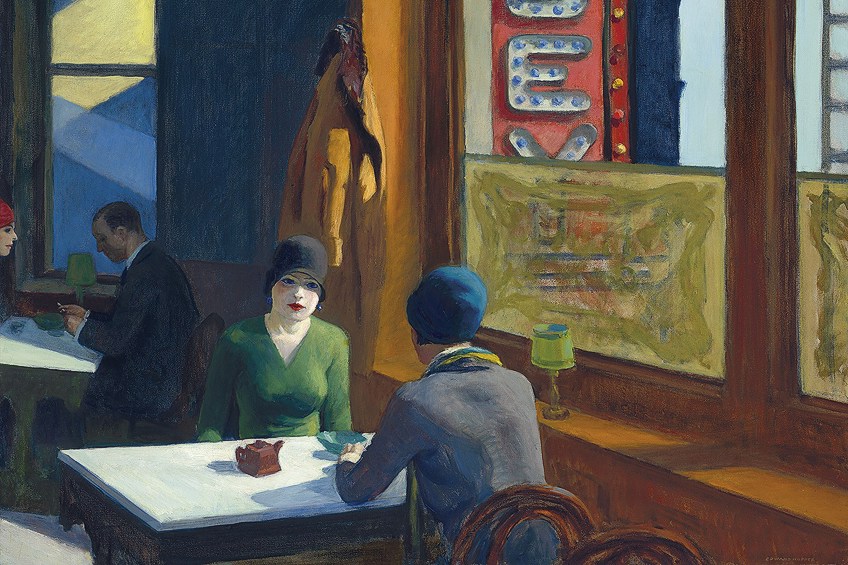

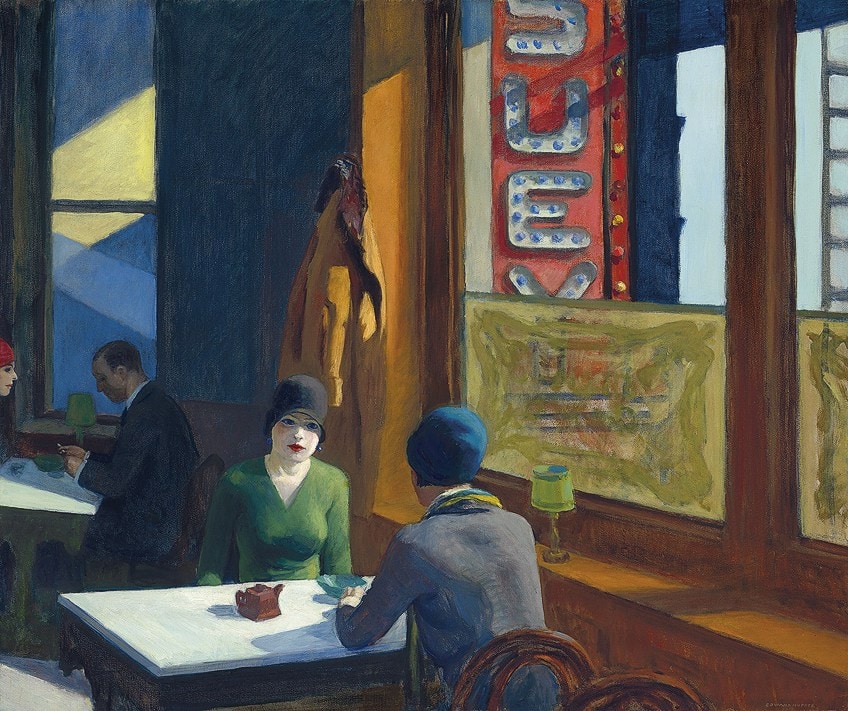

- The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, had an exhibition in 2007 that concentrated on Hopper’s finest works (about 1925 to the mid-20th-century). Thirty watercolors, fifty oil paintings, and twelve prints were on display, including fan favorites Chop Suey, Nighthawks, and Lighthouse and Buildings. The National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and the Art Institute of Chicago organized the exhibition.

Edward Hopper’s artwork continues to be showcased and admired around the world regularly with exhibitions held as recently as 2020 at the Fondation Beyeler. From Edward Hopper’s drawings as a child, through his watercolors and oil paints, and even Edward Hopper’s prints, his masterful yet sorrowful artworks remain an honest and unique peak at American life.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Were Edward Hopper’s Paintings Renowned For?

Hopper, the artist, is often regarded as the most important realism painter in 20th-century America. Though Hopper also produced in printmaking and watercolor, his oil paintings are most renowned for conveying a sense of sorrow or solitude. However, his perception of reality was subjective, representing his own disposition in the desolate cityscapes.

Did Hopper the Artist Suffer From Depression?

Edward Hopper was a highly contemplative person. According to rumor, Hopper struggled with depression, and the isolation of the people in many of his works (including when they were in crowds) represented his own melancholy. Edward Hopper’s source material and manner remained similar over the course of his 60-year tenure. He died from natural causes, however.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Edward Hopper – An Introductory Edward Hopper Biography.” Art in Context. November 7, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/edward-hopper/

Meyer, I. (2021, 7 November). Edward Hopper – An Introductory Edward Hopper Biography. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/edward-hopper/

Meyer, Isabella. “Edward Hopper – An Introductory Edward Hopper Biography.” Art in Context, November 7, 2021. https://artincontext.org/edward-hopper/.