Holocaust Art – Significant Examples of Holocaust Survivor Art

Artists from all around the world, as well as survivors, have used Holocaust artworks to express their feelings about the traumatic event. Nevertheless, the very presence of art from the Holocaust might cause stress in some people. Holocaust survivors created significant works that document or respond to their circumstances, such as diaries, drawings from the Holocaust, Holocaust paintings, and even Holocaust graffiti art. These Holocaust artworks depict the atrocities they witnessed in ghettos and concentration camps.

What Was the Holocaust?

The Nazis slaughtered almost six million European Jews during the Second World War. The term “Holocaust” refers to this atrocity. Numerous factors contributed to the Holocaust. The Nazis’ will and ability to annihilate the Jewish population is its primary motive. However, their desire for blood didn’t just appear overnight. It is important to evaluate the antisemitic Nazi ideology in the larger context of historical antisemitism, contemporary racism, and nationalism.

Despite being a delicate subject, it has a place in the realm of art because of the ability of art to soothe the wounds of the past.

Understanding the Significance of Holocaust Survivor Art

The Holocaust artworks on display examine a variety of reactions to the Holocaust, ranging from the intensely emotional responses of victims to the more journalistic method of official war artists documenting the scenes of Bergen-Belsen following its release in April 1945.

Some of the artists created their drawings from the Holocaust in the camps and slums, while others utilized Holocaust survivor art to represent their post-liberation experiences.

Many of the survivors who settled in Britain after WWII gravitated to producing art from the Holocaust as a way to cope with their tragedy. Many of them made it challenging to speak up, and in the years after the war, they were not always urged to do so. Their Holocaust paintings reflect the enduring legacy of loss, despair, and marginalization of the Jewish people.

Several women were able to make art while imprisoned during the Holocaust. While some artists worked secretly, others were commissioned by Nazis to make artworks in return for food. Female painters utilized aspects such as idealization, naturalism, comedy, and satire in their creations, revealing their wish to escape the environment they suffered in. At the same time, their drawings and paintings show how they preserved their humanism and compassion despite the atrocities they endured.

Communal living, cleanliness and sanitation, wire fences, and nutrition are all common topics and imagery. Many of the works created were journalistic in nature, concerned with commemorating both the artists’ position and the themes of the works.

Lama Sabachthani [Why Have You Forsaken Me?] (1943) by Morris Kestelman

| Date Completed | 1943 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 117 x 153 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

Morris Kestelman was raised in the East End of London in a Jewish immigrant household. Kestelman received a bursary at the Central School of Art in 1922 and then further went on to attend the Royal College of Art. Kestelman worked in theatrical sets and costumes in addition to abstract art.

Upon word of the death of the Jewish people reaching England in the early 1940s, he was among the first creatives to react, naming his work Lama Sabachthani after Psalm 22: “My God, my God, why have you deserted me?”

Emotional upheaval pervades the image, which depicts a number of Jews who appear to be in anguish over being forsaken or abandoned by God. They are surrounded by disaster and loss, standing among blazing buildings and mounds of unburied remains. Women dominated this artwork by being positioned immediately in the foreground. Some lift their arms in sorrow, pleading with God to save them, while others appear to have relinquished in despair. This piece is an unusual and very instantaneous British creative reaction to news of confirmed crimes against Jews in seized Poland.

“Who understood what and when?” is a difficult issue for Holocaust scholars to answer. Is the title’s inquiry aimed at nations beyond Europe as well?

Prisoners Carrying Cement (1944) by Bill Spira

| Date Completed | 1944 |

| Medium | Ink on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 11 cm x 17 cm |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

Bill Spira was a cartoonist from Austria who escaped to Paris soon before World War II began. Following short incarceration in France, he started to work as a forger for the Emergency Rescue Committee, which assisted artists and academics fleeing Nazi persecution. In 1942, Spira was transported and imprisoned in many concentration camps, such as Blechhammer. Blechhammer’s captives were pushed on a death march to Terezn in January 1945, where Spira stayed until the camp was liberated by Soviet troops in May.

Prisoners Carrying Cement is one of a collection of cartoons created by Spira while incarcerated in Blechhammer. He and other artists bartered their creations for food, clothing, and other necessities with POWs, civilian employees, and the SS.

The cartoons in the Imperial War Museum (IWM) collection were given to the museum by the relatives of a British officer who was also imprisoned at Blechhammer and had obtained the sketches in exchange for cigarettes.

Women with Boulders (1945) by George Mayer-Marton

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Watercolor on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 57 x 79 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

George Mayer-Marton was raised in Gyor, Hungary, and was a soldier in the Austro-Hungarian Army all throughout World War I. He pursued painting in Munich and Vienna from 1919 until 1924. He moved to England in 1938 to evade Nazi Germany, while his parents stayed in Gyor. Mayer-Marton did not hear of his parents’ death until 1945 when he created Women with Boulders after learning that they had been transported from Gyor’s ghetto and executed.

His artwork depicts a desolate scene with two lone female characters. The boulders resemble stones put on Jewish tombs to guard the corpse as it awaits the resurrection.

Death March (1945) by Jan Hartman

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Gouache on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 22 x 30 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

In order to avoid the anticipated German bombardment of Prague, Jan Hartman relocated to the Czechoslovak countryside in September 1938 together with his parents and older brother Jiri. In spite of the efforts of his family to flee Czechoslovakia, Hartman, and his sibling were sent to the Terezin camp in 1942.

The brothers were detained at Czestochowa, Auschwitz-Birkenau, and Buchenwald in the years that followed when they were split up. After their rescue in the spring of 1945, Jan and Jiri were united. Years later, Jan Hartman discovered that his parents had perished in Auschwitz. He started a set of works shortly after arriving back at his house that captured his impressions of the camps:

“I guess it was in ’45, I must have produced them as soon as I could since it was my personal way of conveying what I had seen. At the time, I was still able to do it, but I couldn’t do it now since I wouldn’t recall how it was. In other words, it was one method of conveying evidence in the same manner that I do it verbally now.”

Belsen 1945 (1945) by Edgar Ainsworth

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Ink wash |

| Dimensions (cm) | 65 cm x 82 cm |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

An elderly, malnourished guy with his back to a pillar is depicted in the composition’s center, resting on a little elevation in the ground over a mound of corpses and wearing just one shoe. It seems that he perhaps has something in his hands. Another man with his back to the observer is sipping from a cup as he leans on the pillar behind him. A group of three people is standing to the left of the composition, watching as a man and a woman raise a body that has shrunken by the shoulders and limbs.

They appear quite healthy and are clothed well, which raises the possibility that they are German civilians who were made to bury the dead at Belsen after the camp was liberated.

A drawing of a lady cradling a child’s back is visible above the head of the main character. Over the deceased, little black dot clouds that resemble flies hover. Living people experience hunger and cold, which is the only distinction between them and the dead. Nobody is speaking since flies are constantly buzzing and are present everywhere. The interns walk about on their own. They are aware that stopping means dying, even though many people do so immediately. It is the Dead. It is challenging to connect any of the body parts with the other colors because hands, heads, legs, and bodies are scattered everywhere in the spectrum.

One of the Death Pits, Belsen (1945) by Leslie Cole

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 62 x 90 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

A large mass grave comprising the malnourished corpses of prisoners from Belsen as seen from one end. More victims are being thrown into the pit by SS guards who are being watched by British soldiers. The Belsen complex may be plainly out in the distance. One of the five trenches that have already been filled under British monitoring is shown by this. There were further earlier trenches that the Germans had dug and filled.

The bodies being thrown in are skeletal in appearance since they were typhus and hunger sufferers.

If the pit was not being properly filled, the S.S. guards were forced to go into the pit and provide some sort of order since they were not too cautious with the dead. Leslie Cole was adamant that she would see the Second World War’s developments firsthand. Cole finally earned a living as a war artist after the WAAC had rejected his application. He traveled extensively, capturing the effects of the war in Malta, Germany, Greece, and the Far East. Human misery was frequently a theme in Cole’s art.

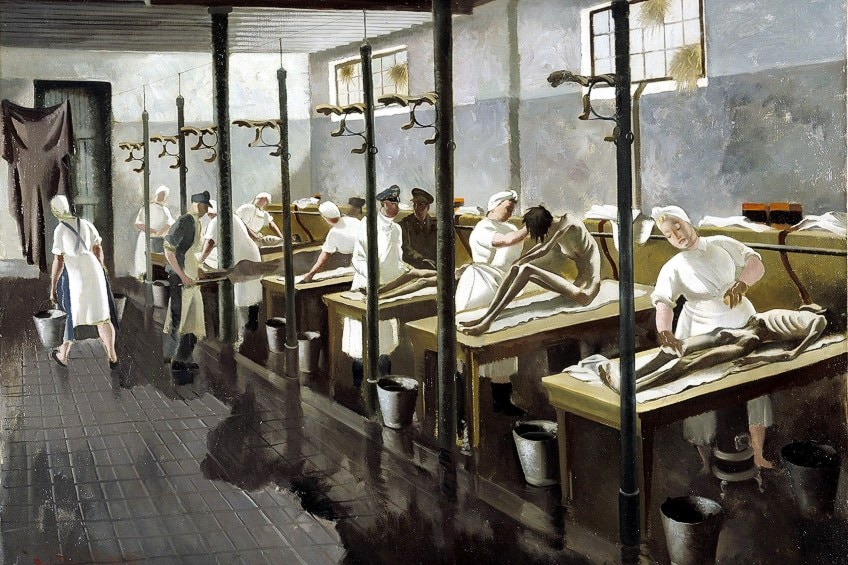

Human Laundry (1945) by Doris Zinkeisen

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions (cm) | 80 x 100 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

This is one of several pieces created by Zinkeisen while she was a Red Cross artist. German medics and captured troops trimmed the prisoners’ hair, washed them, and applied anti-louse powder before transferring them to a makeshift hospital established by the Red Cross, which was housed in a barn with roughly 20 beds.

The forced interactions between the malnourished and weak former prisoners and the strong medical team caring for them are what create tension in the composition.

We can see a row of wooden tables, the first three of which had an underweight person seated or sleeping on them. A person washing each of the statues is either a male or woman wearing a white uniform. Every table has a metal bucket at the base, and a lady can be seen leaving the room while holding a bucket in each hand. Low reflective laminated glass is used for the glazing. There is a backboard. It is a foam-centered backboard that is held together by metal plates and coated with paper tape.

Possibly the most powerful piece created by any of the modern artists is “Human Laundry”.

The contrast between the well-fed, rounder figures of the German hospital personnel and the gaunt bodies of their victims serves as an excellent motif for Zinkeisen. Although the artist subsequently alludes to “the German prisoners,” in reality, they were nurses and medical professionals sent in to help from a nearby German military hospital. Before being taken to the neighboring temporary Red Cross hospital, the camp prisoners had to be cleaned up and de-loused to stop the spread of typhus.

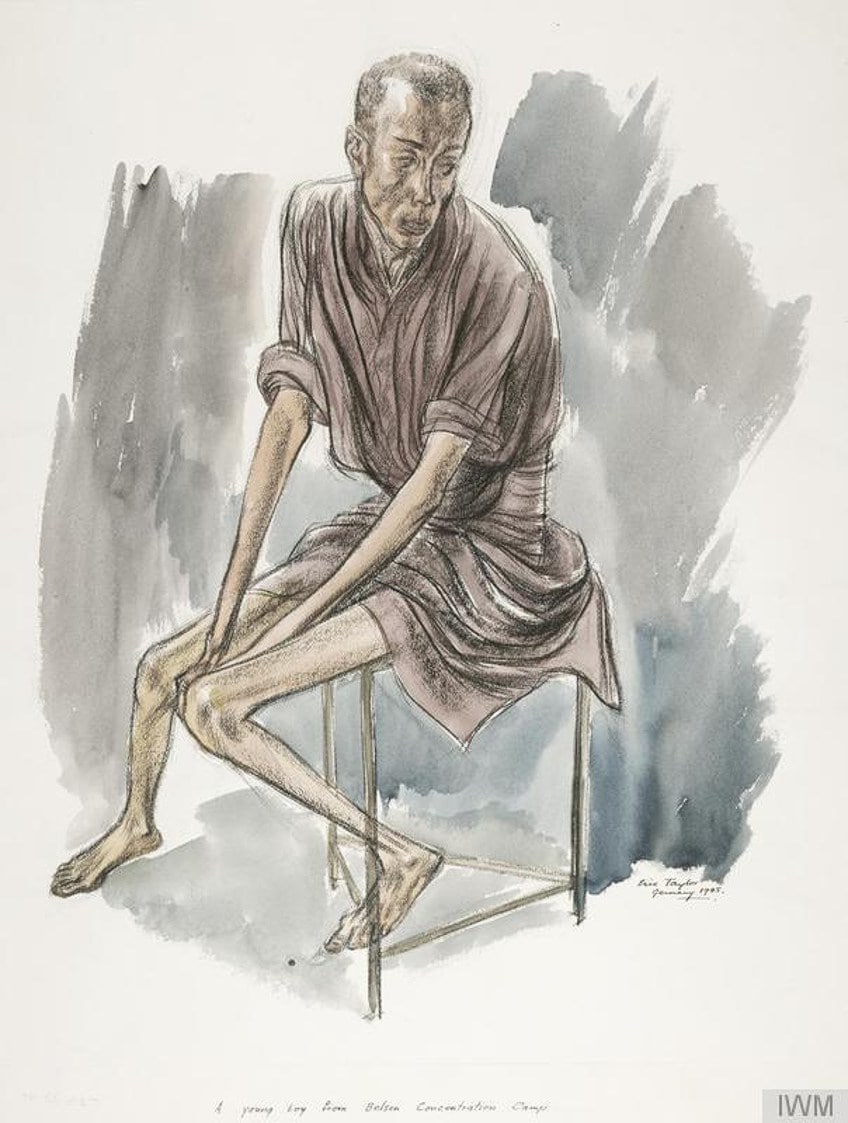

A Young Boy From Belsen Concentration Camp (1945) by Eric Taylor

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Watercolor |

| Dimensions (cm) | 58 x 47 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

Taylor once said: “When the Belsen concentration camp was taken over, I sketched the dead and almost any survivors, and I personally observed all the other horrifying realities of war. Any attempt to put into words the total impact of this event on my work, in my opinion, seems to diminish what I’m trying to convey in my sculptures or paintings. It means a great deal.”

By the start of the Second World War, Eric Taylor, was already a well-known painter, and printmaker. He enrolled in the Royal Artillery and Royal Engineers in 1939.

One of several painters who saw the camp soon after it was freed, he was among the first revolutionaries to arrive at Bergen-Belsen. It was challenging to depict human depravity on such a large scale, and Taylor’s most powerful photos concentrate on lone people, portraying the numb emotional condition that so many survivors shared. The young boy’s gaze appears to be lamenting the passing of so many invisible friends and family members.

We are forced to see his aging as a result of malnutrition and illness as viewers.

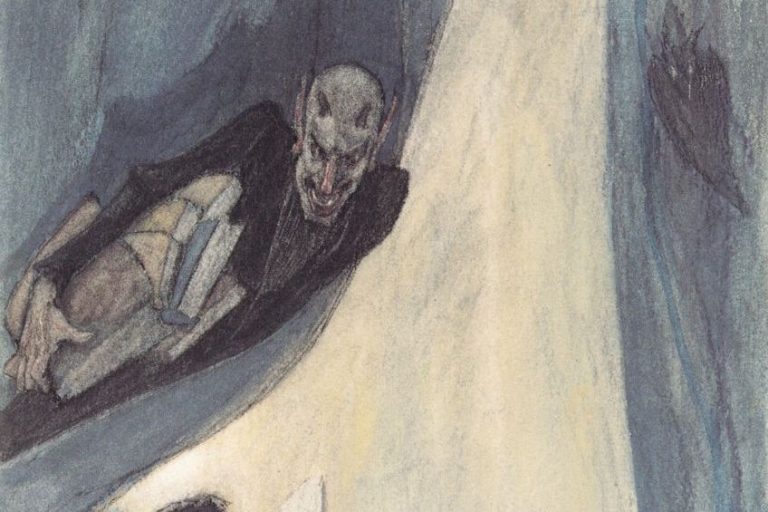

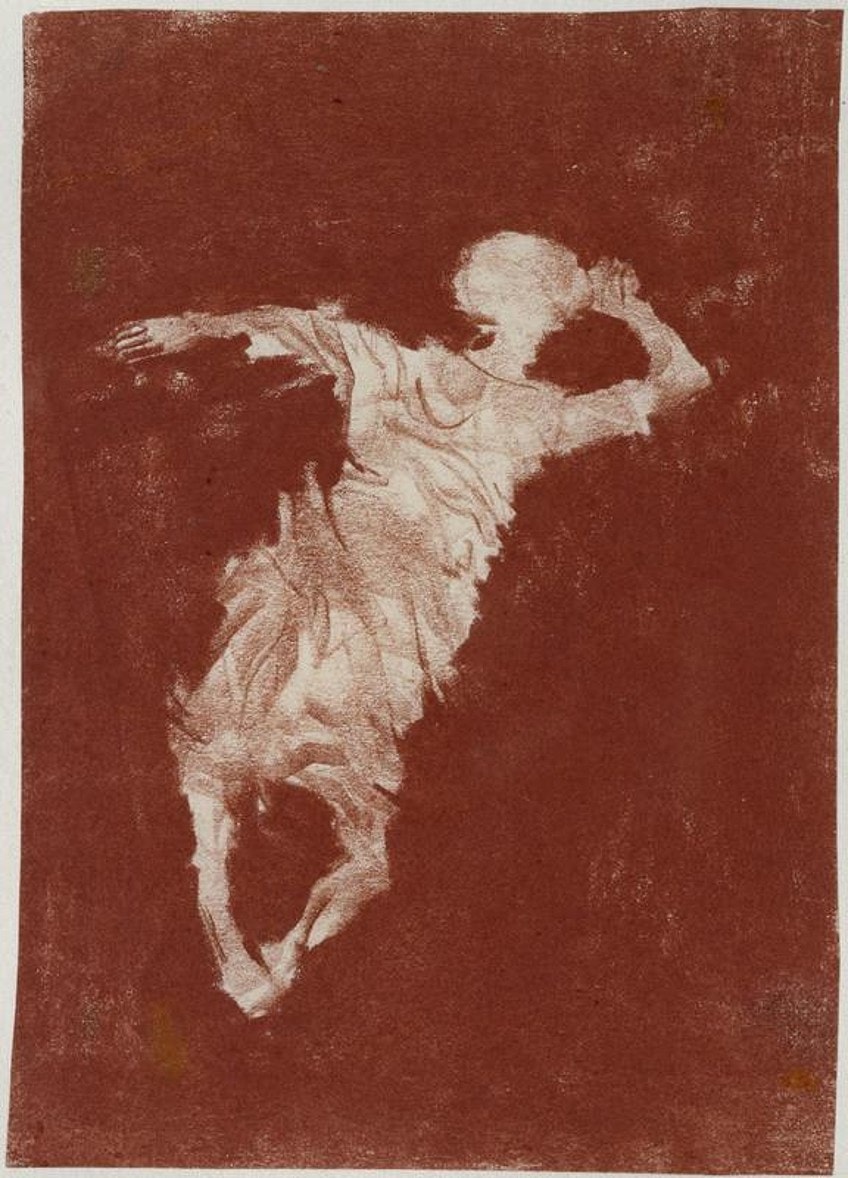

Notes From Belsen Camp (1945) by Mary Kessell

| Date Completed | 1945 |

| Medium | Sanguine crayon on paper |

| Dimensions (cm) | 20 x 25 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

Kessell was one of only three recognized female military painters who worked outside of England during World War II. Four months after the camp’s liberation, she arrived there, and her perspective of it was very different from that of artists like Cole, Zinkeisen, and Taylor. When she visited, Belsen had been converted into a facility for displaced people who were awaiting their return to their homes, many of whom were Belsen survivors:

“Children giggle, adore you, and grasp your hand as they all start to live once more. Everything I saw astounded me; it was thrilling and really touching. Relationships are discovered, and convoys departing from the main plaza of their respective nations are decked with flags and greenery.”

Kessell created a number of tender and compelling illustrations of girls and women. In order to further explain what she saw and experienced at the time, she also kept a detailed journal about her adventures in Germany. She depicts a female refugee being hoisted and carried toward transportation and a chance at survival in Notes from Belsen.

What appears to be a picture of sadness really has a hopeful undertone.

The Death Cart – Lodz Ghetto (1980) by Edith Birkin

| Date Completed | 1980 |

| Medium | Acrylic on hardboard |

| Dimensions (cm) | 91 x 71 |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

In this unsettling picture, people drag white-sheeted corpses along a city street to a horse-drawn wagon. From windows and entrances, other individuals observe while their features mostly resemble skulls. When Poland was under Nazi occupation in 1941, Birkin and her relatives were transferred from their home in Prague to the Lódz ghetto. Her parents passed away a year after moving here.

Birkin was taken to Auschwitz in 1944 and then moved to a different camp in eastern Germany where she was used as slave labor in a subterranean weapons factory. She was sent to the Bergen-Belsen camp in March 1945 but was freed the following month. Later, she made her home in Britain.

The gloomy, lonesome, and desperate feelings that so many people in the ghetto experienced are represented by the wide-eyed features and dark purple blues in this picture.

Birkin declared, “I developed a visual language that allowed me to translate my ideas into the canvas. I wanted to depict what it was like to be a person in the malnourished, bizarre-looking body, cut off from loved ones forever.” The Lódz ghetto, which was built for Jews in Poland and was walled off with barbwire, was the second-largest after Warsaw. In the ghetto by 1942, 100 enterprises produced commodities, such as fabrics for German Army uniforms.

The ghetto’s inhabitants endured appalling labor conditions, sickness, and famine, but thanks to its output, it lasted until August 1944, when it was the last in Poland to be destroyed.

Benjamin (1982) by Shmuel Dresner

| Date Completed | 1982 |

| Medium | Acrylic on newsprint |

| Dimensions (cm) | 94 cm x 37 cm |

| Current Location | Imperial War Museum |

Shmuel Dresner was born in 1928 in Warsaw. When he and the other Jewish citizens of Warsaw were pushed into the ghetto, he was 12 years old. Dresner was apprehended and detained as a slave laborer in many camps. Dresner arrived in England in 1945 and spent some years in treatment centers, where he began painting. Benjamin (1982) is a memorial to the artist’s close friend, whom he had met while both were imprisoned during WWII.

He depicts Benjamin as cheery and positive despite being detained in a camp for two years.

Dresner’s positivity helped him cope with the loss of his father in 1943. Benjamin and Dresner were summoned one day to volunteer for deportation. Benjamin was eager to go forward because he believed those summoned earlier would be transferred by train. Dresner concealed himself for unknown reasons.

He subsequently discovered that everyone who had traveled by rail, including Benjamin, had been killed. Dresner worked for many years to build visual elements to relate to his memories. The work’s focus is on Benjamin’s memories. Dresner uses parallels to damage and violence through the ripped and burned papers from which he crafts the image, but avoids detailed descriptions of their anguish and misery.

Art from the Holocaust made by survivors of genocide illustrates the various human reactions to oppression and the annihilation of one’s culture and life, whether done in a humorous, fantasy, or realistic manner. Drawings from the Holocaust, as well as Holocaust paintings, were often made by people in situations where proper art supplies were not available. Yet, Holocaust survivor art has continued to educate and touch the masses due to its highly emotive content.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Holocaust Graffiti Art?

EURO M arranged a number of activities in Barcelona to commemorate the International Day of Remembrance for Holocaust Victims. One of the events, organized by Nuria Ricart, a Fine Arts instructor at the University of Barcelona, was created to raise awareness of that period of history through an intervention in public space. She developed a transitory engagement at Barri Gotic in Barcelona with young pupils from the creative division of Moisès Broggi public high school alongside urban artist Roc Black block. Following a speech to the student body by historian Jordi Guixé, 12 students were permitted to assist the artist in the creation of a Holocaust mural.

Where Can One See Holocaust Artworks?

One place where you can see these artworks for yourself is Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum. The Museum’s collection of art associated with the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp is exceptional and the world’s largest of its type. Because of its historical and emotional significance, camp art is extremely significant, having a global message that everyone who views it can comprehend. These artistic works, created under tremendous risk, are an extraordinary and evocative record of a historical period. They embody the feelings that followed the convicts on a daily basis, which are difficult to recreate nowadays.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Holocaust Art – Significant Examples of Holocaust Survivor Art.” Art in Context. August 1, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/holocaust-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 1 August). Holocaust Art – Significant Examples of Holocaust Survivor Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/holocaust-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Holocaust Art – Significant Examples of Holocaust Survivor Art.” Art in Context, August 1, 2022. https://artincontext.org/holocaust-art/.