Woodcut Art – Exploring the Art of Relief Printmaking

What is a woodcut? Woodcut printing is a process in which a woodcuts artist carves an impression onto the face of a woodblock using gouges, keeping the printing areas flush with the top while eradicating the non-printing portions. Sections where the woodcut artist trims away contain no ink, but symbols or pictures on the surfaces have been covered in ink to form the woodcut prints. Woodcutting art is thus created when the surfaces are coated with ink by running over the top with an ink-covered roller, producing ink on the level surface but not in the non-printing portions.

What Is Woodcutting Art?

Since its inception in China, woodcut printing has moved around the globe, from European regions to regions of Asia, and even to Latin America. Relief printmaking on fabrics was recognized in Europe as early as the beginning of the 14th century, but it saw little progress until paper was created in Germany and France around the close of the 14th century. Although the woodcutting art medium was frequently utilized for common illustrations in the 17th century, no famous woodcuts artists used it.

How Woodcut Printing Labor Was Divided

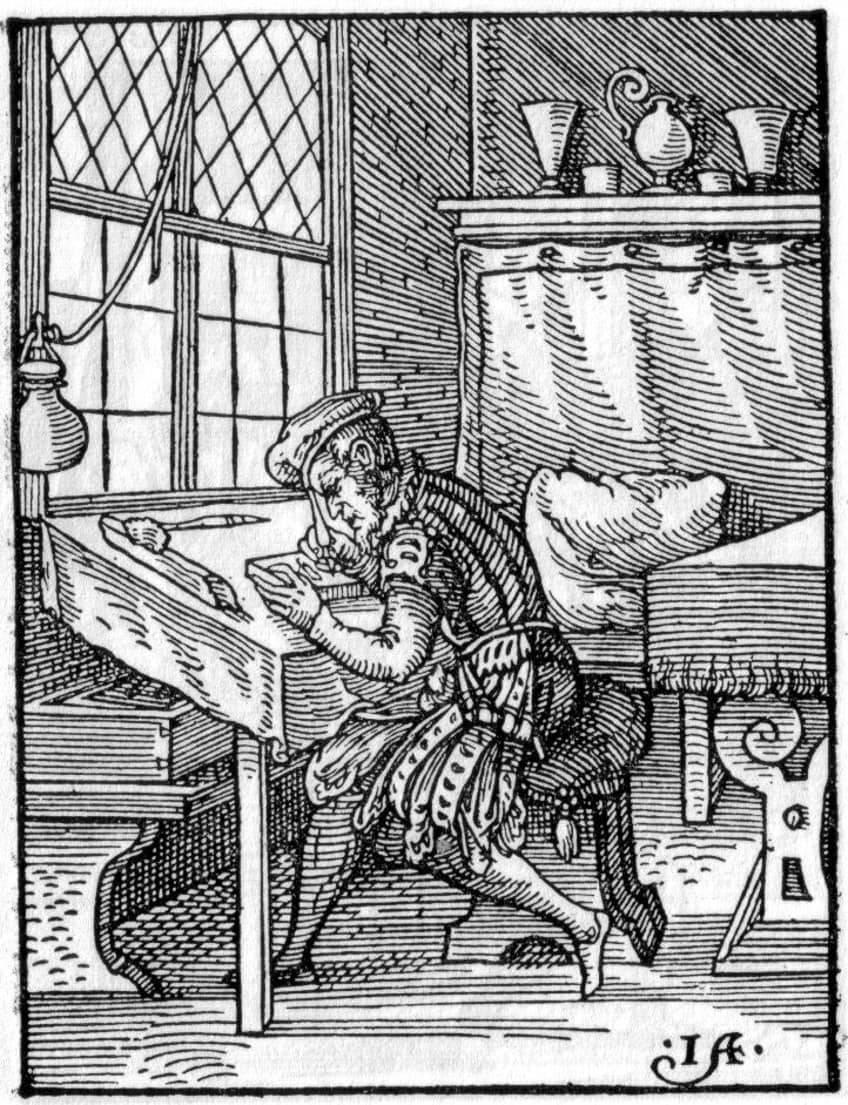

Traditionally, in both East Asia and Europe, the designer just created the woodcut design, leaving the block-carving to expert artisans known as block-cutters or Formschneiders, some of whom were well-known in their own right. The best-known of them are the 16th-century Hans Lützelburger, Hieronymus Andreae, and Jost de Negker, all of whom owned studios and also worked as publishers and printers. The Formschneider then forwarded the block to specialized printers. The blank blocks were manufactured by other professionals.

That’s why, in exhibitions or publications, woodcut prints are occasionally characterized as “designed by” instead of being “made by” a creator; nevertheless, most sources do not make this difference.

The division of labor has the benefit of allowing a skilled artist to quickly adjust to the medium without having to learn how to use carpentry equipment. There were several ways to transmit the artist’s sketched image onto the wood for the carver to adhere. Either the design was done straight on the block (typically after it had been whitened) or a sketch on paper was pasted to the blocks. In any case, the artist’s design was obliterated during the slicing procedure.

Tracing was one of the other ways employed. In the early 20th century, several artists in both East Asia and Europe began to execute the entire process themselves.

Methods of Relief Printmaking

Printing requires less pressure than intaglio processes such as engraving and etching techniques. To make an acceptable print using the relief approach, just ink the blocks, bringing it into consistent and uniform contact with the cloth or paper. In Europe, a number of woods were often utilized, notably boxwood and many fruit and nut woods such as cherry or pear; whereas the timber of the cherry species was preferred in Japan. There are three printing processes to take into account:

- Stamping: Many textiles and most early European woodcuts manufactured between 1400 and 1440 were made with this technique. The fabric was placed on an even surface, with the block then positioned on top of the paper or fabric, and the rear side of the block was pressed or hammered.

- Rubbing: Reportedly the most popular way of printing on paper in the Far East at any and all periods. Later in the 15th century, it was commonly used for European woodcutting art as well as for textiles. From approximately 1910 until the present, it was also utilized for numerous Western woodcuts. The fabric is placed on top of the block, which is placed face-up on a table. A hard mat, a straight piece of wood, or a leather fronton is used to rub the back of the block.

Later, elaborate wooden gears were utilized in Japan to assist in keeping the woodblock absolutely still and to provide the correct pressure throughout the printing procedure. This was particularly useful when various colors were incorporated and had to be precisely put atop prior ink layers.

- Printing at a press: Presses appear to have been utilized in Asia only recently. Printing presses were employed for European block-books and prints beginning from 1480, and earlier for woodcut manuscript images. Basic weighted pressing machines may have been used in Europe prior to the printing press, but there is no clear proof.

The Art of Woodcut Prints

Woodcut printing began in antiquity in China as a means of printing on fabrics, and subsequently on paper. The earliest woodblock printing remnants that have survived are from China, dating from the Han period, and are made of silk imprinted with three different colors of flowers. The Chinese technology of block printing was brought to Europe in the 13th century.

Paper came to Europe a bit later and was being created in Italy by the end of the 13th century, as well as in Germany and Burgundy by the end of the 14th century.

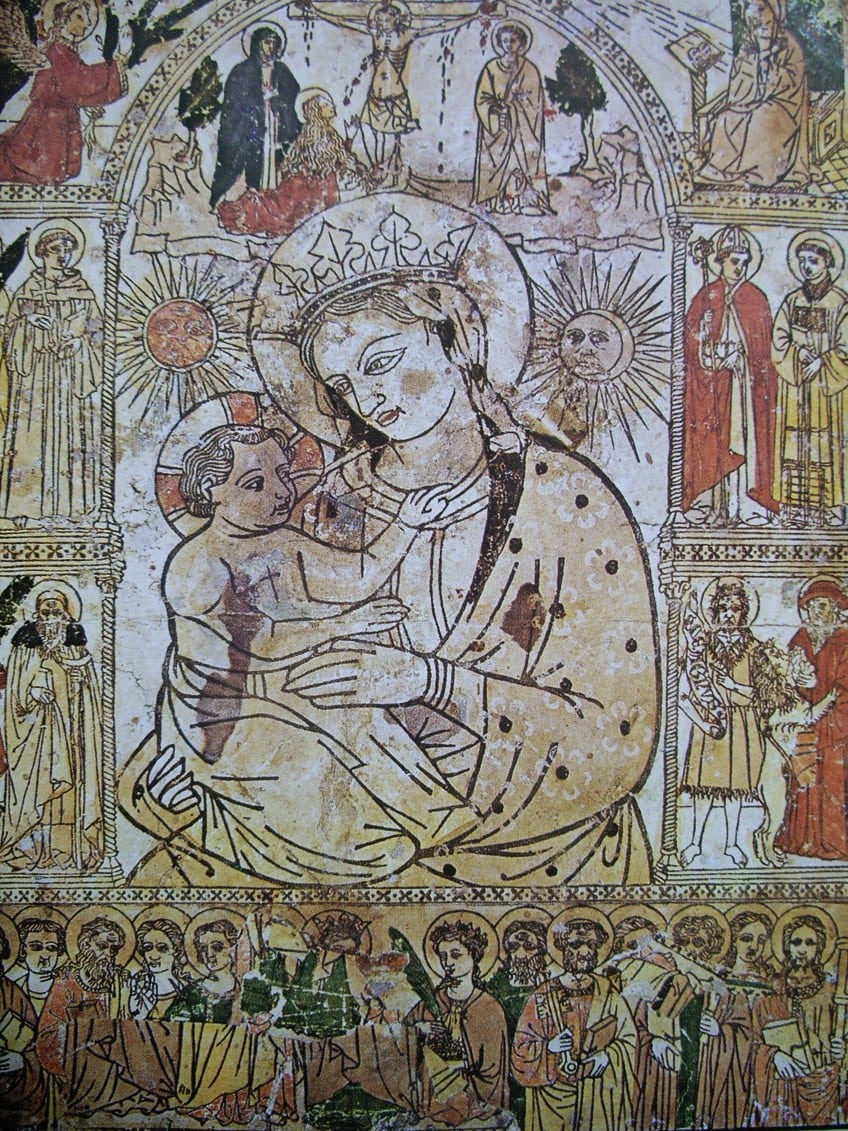

In Europe, woodcut printing is the earliest method utilized for old master prints, having developed around 1400 by employing existing printing processes on paper. Madonna of the Fire, at the Cathedral of Forl, Italy, is one of the most antique woodcuts on paper that may still be seen today. The boom in sales of inexpensive woodcuts in the mid-century resulted in a drop in quality, and many famous woodcuts from this period were rough.

The invention of hatching came much later than that of engraving. From around 1475, Michael Wolgemut was influential in making German woodcuts more complicated, and Erhard Reuwich was the first to utilize cross-hatching, which is significantly more difficult to produce than etching or engraving. Both of these painters mostly made book graphics, as did a number of Italian creators who were elevating quality in the country at the same time.

Albrecht Dürer’s woodcuts towards the end of the century elevated the woodcuts of the west to a degree that, perhaps, has never been exceeded, and substantially elevated the stature of the “single-leaf” woodcut.

Because both woodcuts and moveable types are relief-printed, they may be simply combined. As a result, until the 16th century, woodcut remained the primary medium for manuscript illustration. The first woodcut book artwork dates from approximately 1461, just a few years after Albrecht Pfister’s creation of movable type printing in Bamberg. From around 1550 until the late 19th century, when interest resurfaced, woodcut was employed less often for “single-leaf” fine-art woodcut prints.

In much of Europe, and subsequently, in certain locations, it remained vital for popular prints into the 18th century.

In Iran and East Asia, art acquired a high degree of technical and creative progress. Moku-hanga, or woodblock printing, was invented in Japan in the 17th century for both literature and the arts. The popular ukiyo-e genre began in the second half of the 17th century, with monochrome prints. After printing, these were sometimes hand-colored. Prints with several colors were later produced. Although it was given a lower standing than painting at the time, Japanese woodcut became an important artistic medium.

White-Line Woodcuts

This method simply carves the picture in primarily thin lines, much like a rough engraving. The block is printed in the traditional manner, with the picture generated by white lines on the majority of the print. Urs Graf, a 16th-century Swiss artist, pioneered this approach, but it became most prominent in the 19th and 20th centuries, frequently in a modified version in which works employed huge sections of white-line juxtaposed with parts in the regular black-line style. Félix Vallotton was the first artist noted for doing so.

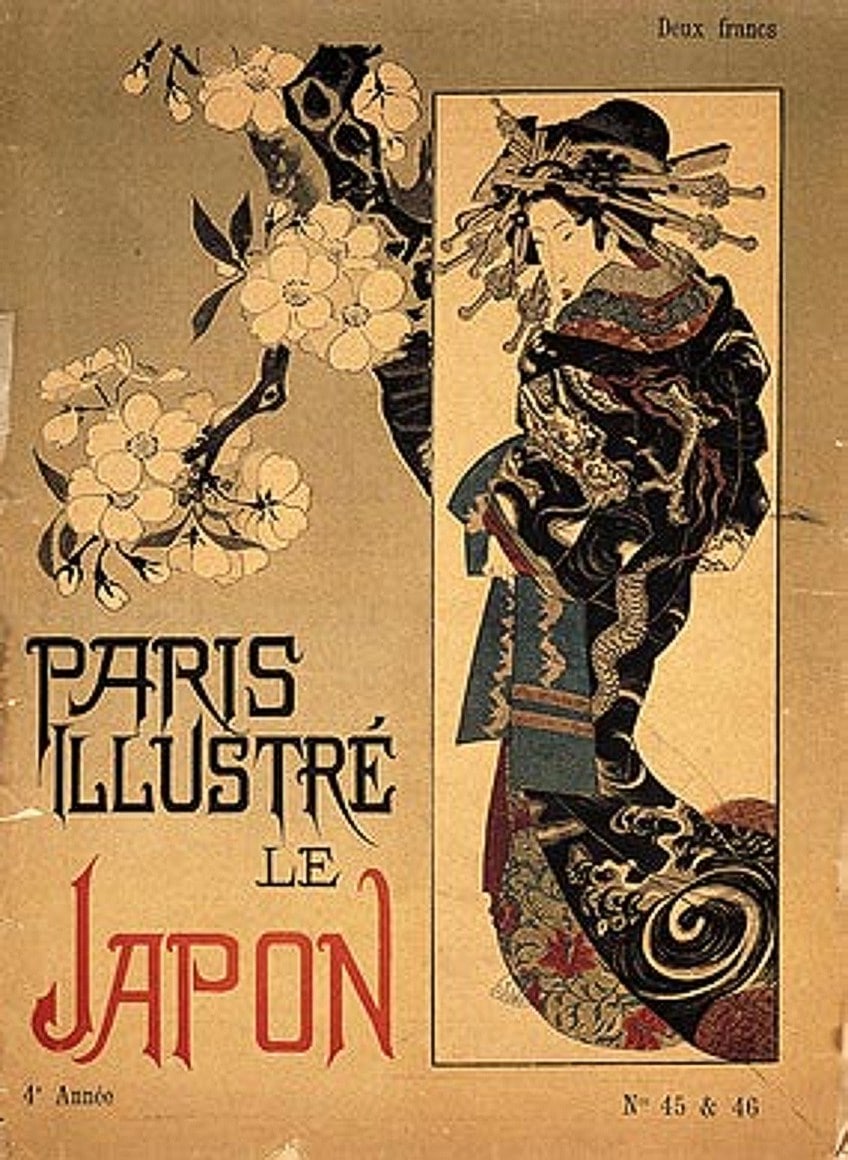

Japonism

Japanese prints began to enter Europe in significant numbers in the 1860s, just as the Japanese culture was becoming acquainted with Western visual art, and were quite fashionable, particularly in France. Many painters were influenced by them, including Pierre Bonnard, Édouard Manet, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Paul Gauguin, Edgar Degas, Félix Vallotton, Vincent van Gogh, and Mary Cassatt.

Jules Claretie coined the term “Le Japonisme” in 1872.

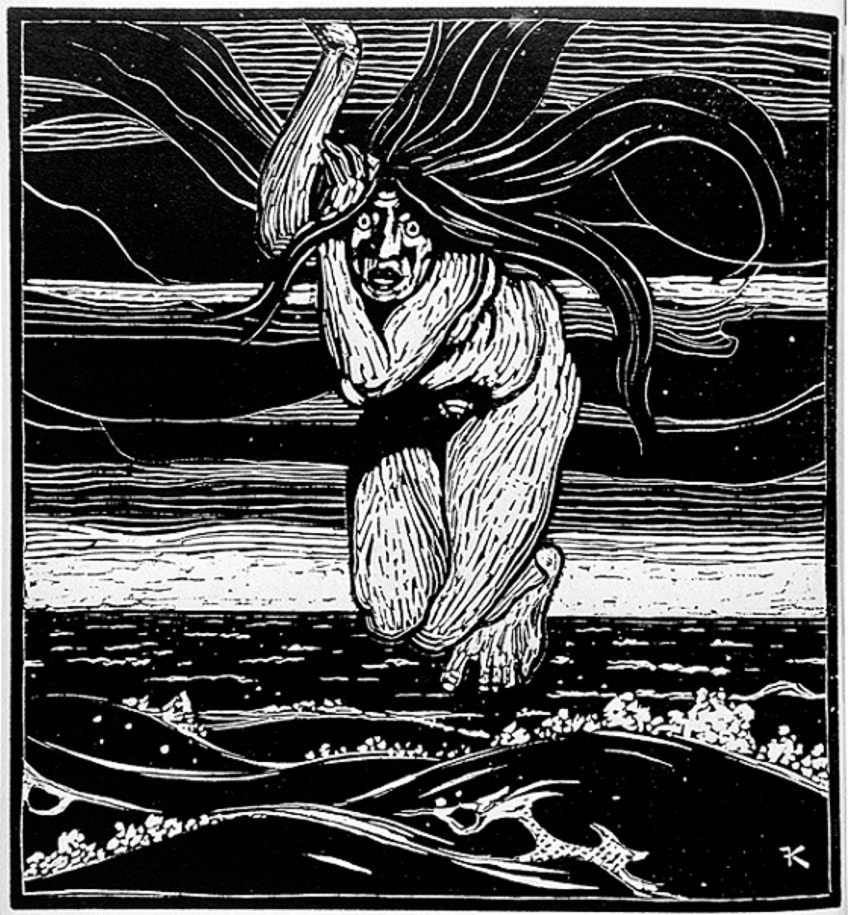

Though the Japanese impact was mirrored in many creative forms, notably painting, it did result in the resuscitation of the woodcut in Europe, which was on the brink of extinction as a major art medium. Except for Félix Vallotton and Paul Gauguin, the majority of the artists mentioned above-employed lithography, particularly for colored prints. Artists, most notably Edvard Munch and Franz Masereel, continued to employ the medium, which gained popularity in Modernism due to the ease with which the entire process, including printing, could be completed in a studio with minimal specific equipment.

The German Expressionists also made extensive use of woodcuts.

The Use of Color

Colored woodcuts were originally seen in ancient China. Three Buddhist pictures from the 10th century are the earliest known. European woodcut prints with colored blocks, known as chiaroscuro woodcuts, were developed in Germany around 1508. Color, on the other hand, would not turn out to become the standard, as it had done in Japan with ukiyo-e and the other genres.

Color woodcuts were mostly employed for printing rather than book covers in Japan and Europe.

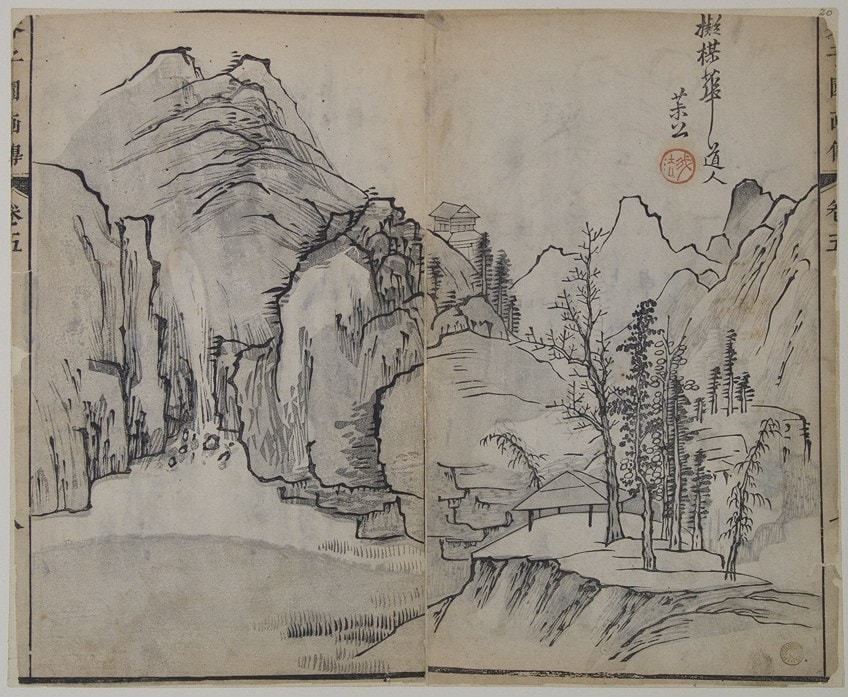

In China, where the single print did not emerge until the 19th century, the opposite is true, and early color woodcuts are usually seen in luxury art publications about painting, the more renowned medium. The first known instance is a book on ink-cakes produced in 1606, and color technique was at its peak in painting books published in the 17th century. A noteworthy example is the Mustard Seed Garden Painting Manual which was issued in 1679.

In Japan, the color method known as nishiki-e in its fully evolved form expanded more extensively and was utilized for prints beginning in the 1760s. The text was almost always monochromatic, as were illustrations in books, but as ukiyo-e became more popular, there was a desire for ever-increasing amounts of colors and intricacy of methods.

Chiaroscuro Woodcut Prints

Chiaroscuro woodcuts were old master prints made with several blocks printed in various colors; they do not always have significant contrasts of light and shadow. They were first created to generate the same effects as chiaroscuro paintings. The real chiaroscuro woodcut created for two blocks was likely invented in Germany in 1509 by Lucas Cranach the Elder, although he retroactively dated some of his first prints and added tone blocks to some prints initially developed for monochrome printing, and was swiftly preceded by Hans Burgkmair.

Despite Giorgio Vasari’s assertion of Italian antecedent in Ugo da Carpi, the first Italian instances date to approximately 1516. Parmigianino and Hans Baldung are two more printmakers that used the method.

The method was widely used in the German states during the early decades of the 16th century, although Italians continued using it throughout the rest of the century, and later painters such as Hendrik Goltzius occasionally used it.

In the German style, one block generally is merely the lines and is referred to as a “line block”, while the other block or blocks have flat patches of color and are referred to as “tone blocks.”

The Italians often utilized merely tone blocks for a totally distinct look, much closer to the original term’s application for chiaroscuro sketches or watercolor works. Torsten Billman, a Swedish printer, invented a variation chiaroscuro method with many gray tones from regular printing ink during the 1930s and 1940s. Gunnar Jungmarker dubbed this style “grisaille woodcut.” It is a method of printing that is regarded as rather time-consuming. It uses many gray-wood blocks in addition to the white and black key blocks.

Woodcut Printing in Modern Mexico

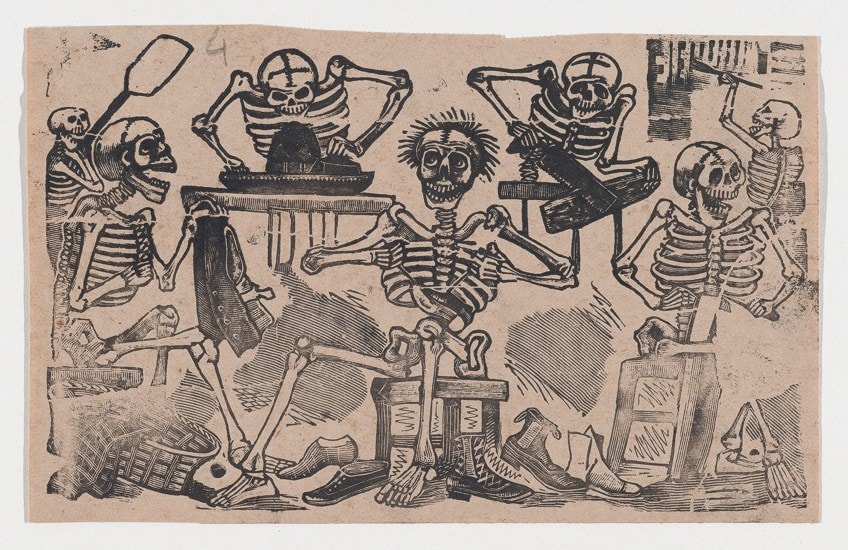

During the early to mid-20th century, woodcut printmaking became a prominent artistic genre in Mexico. Throughout the era of the Mexican Revolution, the media was employed to transmit political agitation and was a type of political engagement. During this period, woodcut art was also utilized to spread leftist ideologies such as communism, socialism, and anti-fascism throughout Europe, China, and Russia.

The method was popularized in Mexico by José Guadalupe Posada, who was acknowledged as the founder of printmaking in Mexico and is regarded as the first Mexican contemporary artist.

Before and during the Mexican Revolution, he was a humorous engraver and cartoonist who promoted the indigenous art of Mexico. He developed the characteristic skeleton images seen in Mexican culture and arts today through woodcutting artworks.

Following the Mexican Revolution, the country experienced political and social instability, with worker strikes, rallies, and marches. These occasions necessitated the use of low-cost, mass-produced graphic prints to be plastered on walls or distributed during protests. Information was usually required to be disseminated to the public at large cheaply and quickly. Many individuals were still uneducated at the time, and there was a drive for mass education after the Revolution.

When the Revolution began in 1910, just 20% of Mexicans could read. Art was thought to be very vital in this cause, and political artists used journals and tabloids to illustrate their thoughts.

Mexico was struggling to find its identity and grow as a cohesive nation during the time. The woodcut aesthetic’s structure and form allowed a vast variety of themes and visual culture to appear united. When etched into wood, traditional, folk imagery, and avant-garde, modern ones had a comparable beauty. A city-like picture of the country and a typical farmer emerged beside the image of the countryside. This symbolism aided politicians who want a cohesive nation. The actual processes of cutting and printing woodcuts also validated many people’s beliefs about manual labor and workers’ rights.

Famous Woodcuts Artists

The woodcut found practitioners in many different creative periods. The approach had a rebirth of attention in Europe at the close of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century when artists such as Edvard Munch and Paul Gauguin made woodcuts that emphasized the method’s linear aspects to great advantage. Here are a few notable famous woodcuts artists.

Albrecht Dürer (1471 – 1582)

| Nationality | German |

| Date of Birth | 21 May 1471 |

| Date of Death | 6 April 1528 |

| Place of Birth | Nuremberg, Germany |

Many artists have employed woodcuts since they have such a lengthy history. Albrecht Dürer, a German painter and printer, trained as a young person to a painter and printmaker at Nuremberg, which was a hub for book printing at the time. Being exposed to printing at an early age must have had an impression on him.

Dürer developed woodcuts into a sophisticated art style, creating dynamic pictures with delicate lines and nuanced shading.

Dürer woodcuts are among the most well-known in the art world. His incorporation of classical elements into Northern art, aided by his understanding of German Humanists and Italian painters cemented his status as one of the Northern Renaissance’s most influential personalities. This is supported by his theoretical book, which includes mathematical concepts, perspective, and ideal proportions.

Dürer woodcuts cemented his name throughout Europe when he was still in his 20s, and he has been widely recognized as one of the greatest Renaissance artists in Northern Europe ever since.

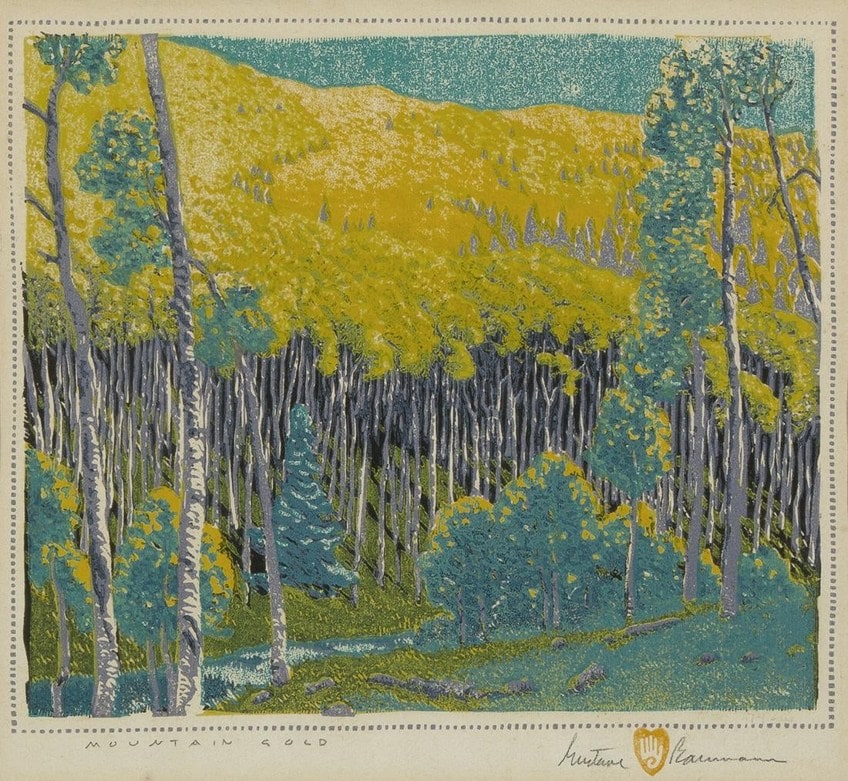

Gustave Baumann (1881 – 1971)

| Nationality | German-American |

| Date of Birth | 27 June 1881 |

| Date of Death | 8 October 1971 |

| Place of Birth | Magdeburg, Germany |

Gustave Baumann used oil-based inks and printed his blocks on a tiny press to follow the traditional European style of color relief printing. This clashed with the vogue at the time among many American painters to use hand-rubbed woodblock prints in the traditional Japanese manner. By this point, he had created his own artist’s seal: an open palm on a heart. At the time, his Mill Pond was the biggest color woodcut made.

These were displayed at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in 1915 when Baumann earned the gold award for color woodcut.

In 1918, he traveled to the Southwest to investigate the Taos artists’ colony in New Mexico. He boarded the train in Santa Fe because he thought it was too busy and sociable. The art museum had just opened the year before, and its curator, Paul Water, convinced Baumann to stay. He befriended several local artists and participated in numerous community festivals in Santa Fe. He created the original Zozobra’s head and sculpted and acted with marionettes. Aside from his well-known color woodcuts, Baumann also created furniture and oil paintings. His paintings showed southwestern vistas, old Indian petroglyphs, garden themes, pueblo life, and orchards.

And with that, we have concluded our look at woodcut prints. Woodcut printing has spread around the world from its origin in China, from European areas to Asian regions, and even to Latin America. Relief printing on textiles was recognized in Europe as early as the early 14th century, but it made little progress until paper was invented in Germany and France around the end of the 14th century. Despite the fact that the woodcut art medium was widely employed for popular images in the 17th century, no notable woodcuts painters used it.

Take a look at our woodcut printing webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is a Woodcut?

Woodcut printing is a technique in which a woodcut artist carves an imprint onto the face of a woodblock with gouges, keeping the printing sections flush with the top and erasing the non-printing portions. The sections where the woodcut artist trims away have no ink, but the surfaces have been coated with ink to make the woodcut prints. When the surfaces are coated with ink by being rolled over the cut with an ink-covered rolling pin, ink is produced on the level surface yet not in the non-printing parts, woodcutting art is made.

How Is a Woodcut Made?

Historically, in both East Asia and Europe, the designer just developed the woodcut design, leaving the block-carving to experienced artisans known as block-cutters or Formschneiders, some of whom were well-known in their own right. Hans Lützelburger, Hieronymus Andreae, and Jost de Negker, all of whom had studios and also worked as publishers and printers in the 16th century, are among the most well-known. The block was subsequently submitted to specialist printers by the Formschneider. Other pros fabricated the blank blocks. As a result, in exhibits or publications, woodcut prints are often referred to as being designed by rather than made by a creator; nevertheless, most sources do not distinguish between the two.

In 2005, Charlene completed her Wellness Diplomas in Therapeutic Aromatherapy and Reflexology from the International School of Reflexology and Meridian Therapy. She worked for a company offering corporate wellness programs for a couple of years, before opening up her own therapy practice. It was in 2015 that a friend, who was a digital marketer, asked her to join her company as a content creator, and this is where she found her excitement for writing.

Since joining the content writing world, she has gained a lot of experience over the years writing on a diverse selection of topics, from beauty, health, wellness, travel, and more. Due to various circumstances, she had to close her therapy practice and is now a full-time freelance writer. Being a creative person, she could not pass up the opportunity to contribute to the Art in Context team, where is was in her element, writing about a variety of art and craft topics. Contributing articles for over three years now, her knowledge in this area has grown, and she has gotten to explore her creativity and improve her research and writing skills.

Charlene Lewis has been working for artincontext.org since the relaunch in 2020. She is an experienced writer and mainly focuses on the topics of color theory, painting and drawing.

Learn more about Charlene Lewis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Charlene, Lewis, “Woodcut Art – Exploring the Art of Relief Printmaking.” Art in Context. March 3, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/woodcut-art/

Lewis, C. (2022, 3 March). Woodcut Art – Exploring the Art of Relief Printmaking. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/woodcut-art/

Lewis, Charlene. “Woodcut Art – Exploring the Art of Relief Printmaking.” Art in Context, March 3, 2022. https://artincontext.org/woodcut-art/.