“The Death of Socrates” by Jacques-Louis David – An Analysis

The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David is a poignant and impassioned portrayal of the handing over of Socrates’ poison while sitting on – quite literally – his deathbed. It is furthermore a famous example of a Neoclassical painting closely connected to the French Revolution – we will explore it in more detail in this article.

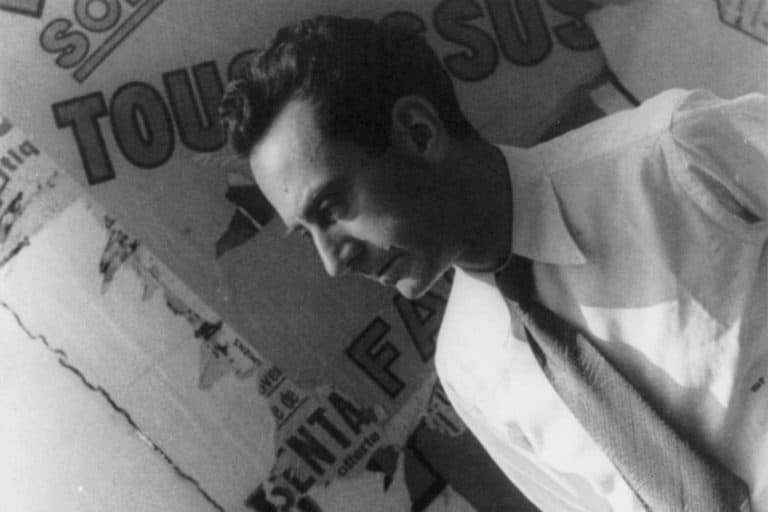

Artist Abstract: Who Was Jacques-Louis David?

Jacques-Louis David was born on August 30, 1748, and died on December 29, 1825. He was born in Paris, France, and became one of the most notable artists of the Neoclassical art movement. He received assistance from the Rococo artist François Boucher who introduced him to the artist Joseph-Marie Vien.

David also studied at the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, where he won a Prix de Rome, which allowed him to study art in Rome for several years.

He was controversial in his ideas and supported various political parties and his art explored these themes through the historical subject matter. This approach influenced and inspired many artists that came after the Neoclassical movement. Some of his famous artworks include the Oath of the Horatii (1786) and The Death of Marat (1793).

The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David in Context

Below we will start with a brief contextual analysis of The Death of Socrates by Jacques-Louis David, looking at the historical events that occurred when David painted it, who commissioned it, as well as how Socrates died.

We will then look at a formal analysis, exploring Jacques-Louis David’s stylistic approach and rendering of the painting – we will utilize several art elements and principles as guideposts to help us understand the visual components that make The Death of Socrates painting.

| Artist | Jacques-Louis David |

| Date Painted | 1787 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Genre | History painting |

| Period / Movement | Neoclassicism |

| Dimensions | 51 x 77 ¼ inches (129.5 x 196.2 centimeters) |

| Series / Versions | N/A |

| Where Is It Housed? | The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The MET), New York, United States of America |

| What It Is Worth | Jacques-Louis David was reportedly paid 10.000 Livres for The Death of Socrates by Charles-Louis or Charles-Michel Trudaine de la Sablière. |

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

It is believed that The Death of Socrates was commissioned by either Charles-Louis or Charles-Michel Trudaine de la Sablière in 1786. However, there are scholarly debates around the validity of this as the painting could have been commissioned by the other Trudaine brother. When Jacques-Louis David completed The Death of Socrates in 1787, the political and social climate was on the cusp of the French Revolution, which started in 1789.

There were various reasons that catalyzed the revolution, especially the inequalities between the people and the monarchy, which was headed by King Louis XVI and his wife Marie Antoinette.

Jacques-Louis David was a supporter of the revolution and reportedly acquaintances with the often-termed tyrant, Maximilien Robespierre, who was a key figure in various parts of the revolution, including the Reign of Terror that occurred around 1793.

Robespierre was also part of the political Jacobin Club, of which David was a member.

However, before the events of the French Revolution Jacques-Louis David’s paintings conveyed revolutionary ideas like republicanism, patriotism, heroism, fraternity, and a return to Classical art subjects and ideals. A notable example of this includes his earlier The Oath of the Horatii (1784), which portrays a scene based on a Roman narrative.

Who Was Socrates?

Socrates was an ancient Athenian philosopher and widely known as the “founding father of Western philosophy”. He reportedly did not write any of his philosophical beliefs and ideals and expressed these through oration.

His legacy was continued through his students Plato and Xenophon, who were also philosophers from Athens.

They wrote various texts that are often referred to as the “Socratic dialogues” related to Socrates’ teachings and dialogues. Plato covered Socrates’ fate – from his trial to his death – in four dialogues, namely, Euthyphro (c. 380 BCE), the Apology (c. 399 to 387 BCE), Crito (c. 360 BCE), and finally, Phaedo (C. 360 BCE).

Phaedo was about Socrates’ time in prison and his imminent death, which was by drinking hemlock – a poisonous plant. However, the question arises: Why was Socrates in prison? He was tried for several crimes, such as “corrupting the youth” with his ideas and philosophies. As a result, he was sentenced to death.

Socrates did not compromise on what he believed in and chose to die instead, surrounded by his students.

Phaedo explored his last dialogues about the soul and its immortality – reportedly the title was also understood to be On the Soul for those who lived during the ancient times. Plato also wrote it from the viewpoint of Phaedo of Elis, who narrated the story to the Pythagorean philosopher Echecrates.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

In the formal analysis below, we will explore The Death of Socrates in more detail starting with a visual description of the subject matter, expanding more on Socrates’ final moments as depicted by Jacques-Louis David, and then a discussion about the artist’s stylistic approaches.

Visual Description: Subject Matter

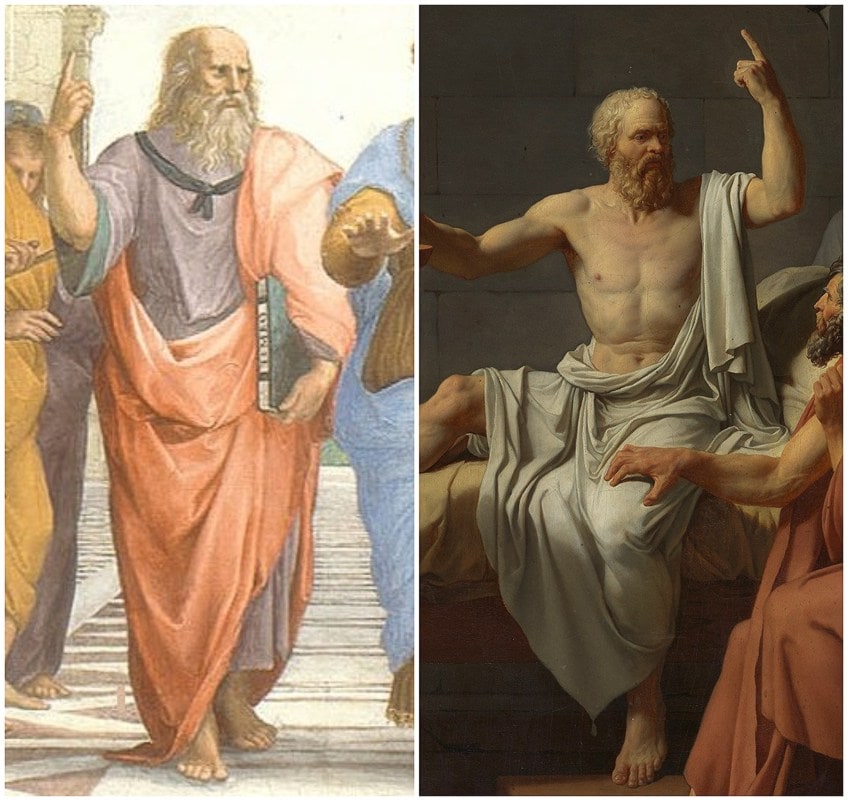

The Death of Socrates painting depicts a gray-walled prison cell with ten men who all appear in anguished emotional states. The central figure of Socrates is sitting on his bed – he is perched almost on the edge of it with his right leg stretched out on it and his left leg hanging from its edge slightly supporting itself on a block on the floor. His left arm and index finger are pointed to the sky.

Interestingly, this corresponds with Raphael’s painting “The School of Athens” (1509-1511), where the central figure of Plato is also pointing his index finger to the sky.

Socrates is seemingly inattentively reaching for a goblet with his right hand while his attention and gaze are on the man sitting on what appears to be a stool made of a stone block. The latter is believed to be Crito, whose right hand is clutched onto Socrates’ thigh. Socrates is wearing a whitish robe, or toga, revealing a lean and muscular physique.

He was apparently older than he appeared, a 70-year-old, but Jacques-Louis David reportedly portrayed him in a more idealized manner to enhance the visual impact and emotional effects of Socrates as a man and a teacher.

There are five figures standing behind Crito, all of whom appear distraught. The furthest figure to the right is holding up his right hand while closing his eyes with his left fingers. Some of the figures are holding their heads in their hands.

There are three figures to Socrates’ right (our left); the closest is handing Socrates poison in a goblet that will ultimately lead to his demise. He is described as a guard by some art sources and wears a red robe. His head and shoulders are drooped, and he is covering his face, as if he cannot look at what is about to happen, seemingly reluctant in his body posture. This is emphasized by his left foot, which appears tensed in its position, as if he is frozen in his tracks, so to say.

Additionally, Socrates’ hand is frozen at the moment when he is just about to reach for the poison, which heightens the dramatic effect of the scene.

At the foot of the bed is an elderly man sitting on what appears to be a wooden or stone block. His head is drooped, and his hands are held in his lap – his right hand is over his left hand – and he is wearing what appears to be a white robe with a white band around his head. His eyes appear closed.

This man is believed to be Plato himself, although he is depicted here as older than he would have been when these events took place, which was in his twenties.

Furthermore, Plato was not at the scene of Socrates’ death and many sources state that Jacques-Louis David depicted the scene to indicate that it was one of Plato’s memories, which is also why Plato is not actively engaged in this scene as the other figures around him are.

Standing to Plato’s right is another man with arms and his forehead resting on the prison wall as if he is completely hopeless and anguished over the events. This man is standing in an arched hallway that leads to the back of the prison cell.

He is also situated in the middleground of the composition, leading our gaze into the background.

In the background, there are three more people walking up a staircase – two men and one woman who is Xanthippe, Socrates’ wife. The woman is looking in our direction, towards Socrates with her right hand raised in a wave – undoubtedly her last goodbye wave.

There are other objects in The Death of Socrates painting; for example, on the bed and the floor are Socrates’ metal handcuffs and their chains, and we can also notice the red marks around his ankles, which show that he has been uncuffed.

Near Plato’s seat on the floor is an inkwell with a pen and a scroll, which is thought to symbolize Plato as the author of the story being told.

On Socrates’ bed is a lyre; some sources have drawn references to Socrates composing music before his death and others have referenced a part of the text, Phaedo, where Socrates referred to music and the soul.

Behind Socrates’ bed is an incense burner on a tall stand; however, there is not a shadow of the incense burner mirrored on the wall, which some suggest could refer to the insignificance of praying.

This is because incense burners often symbolized prayers as offerings to God(s).

We will also notice Jacques-Louis David’s initials on Plato’s seat and on Crito’s seat. Some sources have suggested a deeper meaning to these. This could be that David felt a connection to both figures and made a connection to himself and them.

Jacques-Louis David apparently worked on several sketches around the theme of Socrates and the scene of his impending death in 1782. However, it was only several years later that he would paint this iconic scene for a commission.

The sketches provide further details about David’s preparatory process, although there have also been extensive scientific studies that reveal David’s painting process too.

Some of the changes that were made include, for example, the hand position over Socrates’ poison; in one of his earlier sketches, his hand is further away from it. In a later sketch, the hand position over Socrates’ poison is closer and almost touching the goblet. However, we will see that David created slightly more space between his hand and the goblet, which heightens the emotional tension of the entire scene.

Color

Jacques-Louis David utilized a “muted” color palette in The Death of Socrates painting. We see various hues of reds, blues, and golden yellows, which create contrast in cooler and warmer colors. The whites from Socrates’ and Plato’s clothing sets them apart from the others around them. Furthermore, there is an unknown light source from the left side of the composition, which highlights the central figure of Socrates revealing his fair skin tone, also adding emotional depth due to what is about to occur.

There is also a contrast created in the color values – Socrates’ highlighted figure has a high color value, and the figures in the shadows around him, have a lower color value.

Texture

Texture as an art element can either be the physical feeling or implied feeling of an artwork, and in The Death of Socrates, we see the smooth surface texture of the paint as well as the implied textures on the soft folds from the clothing, which is contrasted with the hardness of the stone wall and floor.

Line

There are various lines in The Death of Socrates painting; for example, the diagonal line created on the wall by the light source from the left creates emphasis and directs our gaze to the central figure. There is also an implied line starting from Plato’s head that introduces the scene behind him.

This further emphasizes his role in the painting as someone remembering what occurred.

Shape and Form

There is an interplay of shapes and forms; the figures appear organic and naturalistic in their forms, which contrast with the other more linear and geometric shapes of the prison cell’s rectangular bricks that compose the wall and floor, the lines that divide them, the squarish shapes from the seats, and the archway to the left that opens to the background.

Space

Jacques-Louis David created an emotionally-heightened space by placing the figures in the shallow foreground – the wall behind the figures brings them into the foreground and almost into our, the viewers, space.

To the left, we see the space recede into the background, which gives the composition a three-dimensionality by creating depth.

Furthermore, David creates a spatial contrast between the receding space to the left and the shallow space to the right, emphasizing the action taking place to the right and balancing it with a calm, emptier space to the left.

“The Death of Socrates” was exhibited in 1787 at the Paris Salon and received positive reviews from various notable figures like Thomas Jefferson, who was the third President of the United States. While this painting portrays an ancient Greek tale of how Socrates died, it also became a beacon of leadership, steadfastness, and heroism. From philosophy to revolution, Socrates has been immortalized as a symbol for those who faced adversity and still stood their ground, even if it meant death.

Take a look at our The Death of Socrates painting webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted The Death of Socrates?

The Death of Socrates (1787) was painted by Jacques-Louis David. He was reportedly commissioned by Charles-Michel or Charles-Louis Trudaine de la Sablière. It was within the Neoclassical art style as well as a painting that portrayed ideals related to the French Revolution, which started shortly after the painting’s completion.

Where Is The Death of Socrates Painting?

The Death of Socrates (1787) by Jacques-Louis David is now housed at The Metropolitan Museum of Art (MET) in New York City, the United States of America. It was previously sold and passed down by several people until it was purchased by the MET in 1931.

Who Is Plato in The Death of Socrates?

Plato is depicted as the elderly man sitting at the foot of Socrates’ bed, to the left of the composition. He was in his twenties when Socrates died and not present at his death. Jacques-Louis David depicted the scene as a so-called memory of Plato.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““The Death of Socrates” by Jacques-Louis David – An Analysis.” Art in Context. August 4, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-death-of-socrates-by-jacques-louis-david/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 4 August). “The Death of Socrates” by Jacques-Louis David – An Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-death-of-socrates-by-jacques-louis-david/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““The Death of Socrates” by Jacques-Louis David – An Analysis.” Art in Context, August 4, 2022. https://artincontext.org/the-death-of-socrates-by-jacques-louis-david/.