Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck – Studying Jan van Eyck’s Iconic Work

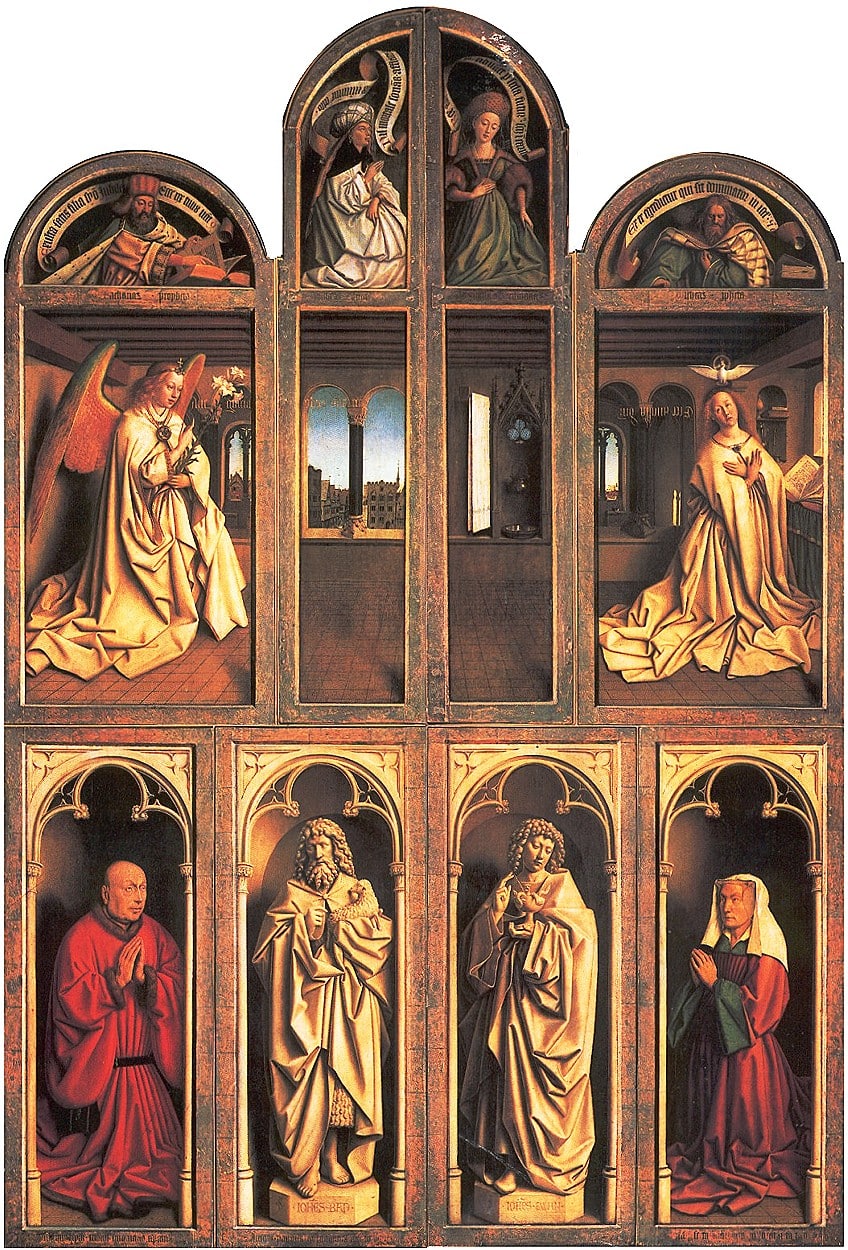

It is a painting of many panels and tales, it has stood the test of Medieval times and underhandedly passed through many hands. This is the Ghent Altarpiece, which is also titled the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb (c. 1425 – 1432). In this article, we will discuss this painting, its meaning, and the many panels that make it one of the most ground-breaking paintings from the Northern Renaissance.

Artist Abstract: Who Was Jan van Eyck?

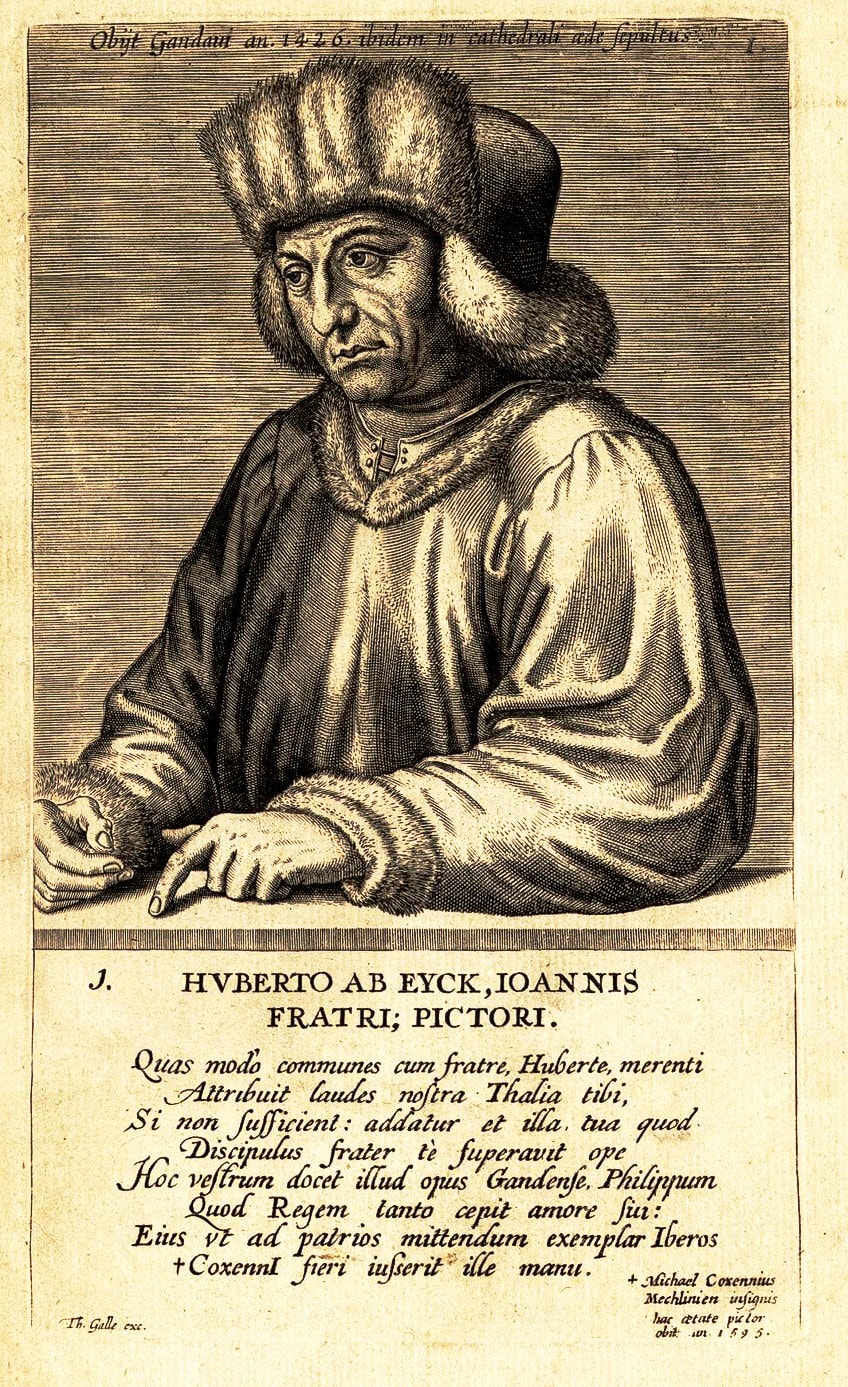

The Early Netherlandish painter known as Jan van Eyck was born in the city of Maaseyck in Belgium. His date of birth has been placed approximately between 1390 and 1395 until 1441, when he died on July 9 in Bruges. Van Eyck had three siblings: one sister, Margareta, and two brothers, Hubert, and Lambert, all of whom were also painters.

He was also believed to have apprenticed with his older brother, Hubert. Van Eyck became one of the pioneering artists of his time, known as one of the Flemish Primitives. He painted religious scenes as well as portraits and was commissioned by many wealthy merchants, of which he was also a court painter for the Duke of Burgundy.

There are many scholarly debates around Jan van Eyck’s life and art, but what is known is that he was masterful with his use of oil paints and became widely known for his techniques with this medium, producing an awe-inspiring realism in his artworks. We have a separate post on Jan van Eyck’s paintings.

The Ghent Altarpiece (Adoration of the Mystic Lamb) (1432) by Jan van Eyck in Context

| Artist | Jan van Eyck |

| Date Painted | c. 1425 – 1432 |

| Medium | Oil paint on wooden panels (polyptych) |

| Genre | Religious painting |

| Period / Movement | Northern Renaissance |

| Dimensions | Open view is 3.5 x 4.6 meters / Closed view is 375 x 260 centimeters |

| Series / Versions | N/A |

| Where Is It Housed? | Saint Bavo’s Cathedral, Ghent, Belgium |

| What It Is Worth | N/A |

The Ghent Altarpiece is also referred to as the Adoration of the Mystic Lamb, it is a polyptych altarpiece, which was believed to have been started in 1425 or more roughly the mid-1420s and completed in 1432. It is a complex painting that might appear confusing at first, depicting a variety of subject matter all in one, leaving uncertainty as to what the meaning or narrative is.

Furthermore, it was painted in exquisite detail, which will leave anyone viewing it, whether in person or online, awestruck and intrigued.

Below, we will discuss a brief contextual analysis of how it was conceived and created and became one of the most popular Early Northern Renaissance artworks in history, as well as one of the most sought after by many. Additionally, we will discuss a formal analysis, looking at the painting in closer detail in terms of the subject matter on its panels.

Contextual Analysis: A Brief Socio-Historical Overview

The Ghent Altarpiece (Adoration of the Mystic Lamb) was commissioned by the wealthy merchant, Jodocus, or Joos, Vijd, and Lysbette Borluut, who was his wife. It was made as part of the Vijd Chapel in the Saint Bavo Cathedral located in Ghent in Belgium.

The Saint Bavo Cathedral was initially known as the Church of Saint John, which was a dedication to Saint John the Baptist. It was built during the 10th century and was initially a wooden chapel structure with later remnants revealing it was also built in a Romanesque style.

During the 13th century, the church was redeveloped and rebuilt into the Gothic architectural style, which resulted in various new additions to the church over time, such as a new chapel that Vijd paid for. This chapel is located off the choir of the cathedral and is named after Vijd and his wife. The Ghent Altarpiece was reportedly celebrated on May 6 in 1432, the year of its completion and unveiling in the Vijd Chapel. Van Eyck painted the two donors on the back panels of the polyptych, the far left is the kneeling figure of Jodocus, and the far right is the kneeling figure of his wife, Lysbette.

The Ghent Altarpiece is about the Biblical story of Jesus Christ, His sacrifice, crucifixion, and how His blood has been lifegiving. It illustrates various Biblical passages, most importantly how the Lamb of God gives blood, referring to the passage in the Book of John, 1:29: “Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world”.

Other sources also point to the Book of Revelations, 7:9, “After this, I looked, and there before me was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, tribe, people and language, standing before the throne and before the Lamb. They were wearing white robes and were holding palm branches in their hands”.

The “Ghent Altarpiece” explores various themes related to sacrifice, blood, resurrection, life, and ultimately salvation. However, some sources have also explored the meaning behind the altarpiece also connected to the commissioners, Joos Vijd and Lysbette Borluut, who were significantly wealthy.

The Quatrain Says It All: Who Was Hubert van Eyck?

In 1823, a quatrain (a rhyming verse/poem/stanza that consists of four lines) was found on the lower frames of the Ghent Altarpiece. It was written in Latin and inscribed on the frame, one of the translations states the following: “The painter Hubert van Eyck, a greater man than whom cannot be found, began this work. Jan, his brother, second in art, completed this weighty task at the request of Joos Vijd. He invites you with this verse, on the sixth of May [1432], to look at what has been done”.

Hubert van Eyck was believed, from the discovered inscription, to have started the Ghent Altarpiece panels, however, during the year 1426, he died leaving the altarpiece to his brother, Jan van Eyck.

Scholarly research from the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage suggests that Hubert painted the underpaintings. There have also been debates around the originality of it and who wrote it; some believe it was written at a later stage, however, due to the quatrain seemingly saying it all it remains attributed to the van Eyck brothers.

The Ghent Altarpiece: Known As the Most Coveted Painting

The Ghent Altarpiece has been known as the most coveted painting in art history and has had many adventures, so to speak, from theft, various damages, and held for ransom, with an ongoing investigation regarding one of the stolen panels, described as a “heist” during 1934. Below is a brief overview of some of the significantly related thefts.

Starting from 1566, it was reportedly stolen by Calvinists who wanted to burn it, and by Napoleon’s soldiers during the French Revolution. Reportedly, four panels were displayed in the Louvre, however, these were returned to Ghent in 1815 by King Louis XVIII.

Also, during 1815/1816 some of the panels were sold to an art dealer and found their way to the Berlin Museum. Some panels were also stolen by Germans during World War I and eventually returned under the Treaty of Versailles. During World War Two, Adolf Hitler also tried to get his hands on the Ghent Altarpiece, along with Hermann Göring. The altarpiece was scheduled to be moved to the Vatican in Italy to be kept safe, which was when Hitler seized it, storing it in the Altaussee salt mines.

It was eventually recovered by the group known as the Monuments Men, officially named the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (MFAA) which was formed from 1943 until around 1946. They were composed of various several hundred members who worked to recover and restore stolen cultural items during the war. In popular culture, there was a film created about the efforts made by this group titled The Monuments Men (2014).

The Just Judges panel has reportedly been one of the unfound panels and replaced by a copied version to complete the altarpiece. Some sources also question the arrangement of the panels and whether these are correctly sequenced due to the altarpiece’s dismantling over time.

Although many will wonder, “where is the Ghent Altarpiece now?”, seemingly being exchanged like a hot potato in the hands of many radicals, dealers, and militia, it is now safely housed in the Saint Bavo’s Cathedral, protected by a bullet-proofed case that is also climate controlled.

Formal Analysis: A Brief Compositional Overview

Below we will explore the Ghent Altarpiece subject matter in further detail looking at the upper and lower registers of the open view as well as discussing the closed view. We will also look at several of the important formal art techniques van Eyck applied in terms of color, light, and perspective.

Subject Matter: The Ghent Altarpiece Layout

The Ghent Altarpiece consists of 24 painted wooden panels, the two outer panels can fold, closing the polyptych, revealing its outer panels, of which there are 12. When the polyptych is opened there are two horizontal parts or levels, this is referred to as “registers”, which consist of 12.

The Opened View: Upper Register

There are seven painted panels along with the upper register of the Ghent Altarpiece. Starting from the far left is the figure of Adam looking inwards towards the other panels, although his head is slightly downcast, his right hand covers his genitalia with several leaves. Above the figure of Adam is a small lunette depicting the two brothers, Cain, and Abel, making their sacrifices to God. Cain and Abel were also Adam and Eve’s “first two sons”.

Directly opposite the figure of Adam, to the far right, is the figure of Eve, also with her head slightly downcast. She is holding a small fruit in her right hand, which is raised while her left-hand rests over her genitalia.

Above Eve is another lunette depicting the murder of Abel by Cain. Both Adam and Eve appear despondent, and according to some sources, this has been debated by scholars that van Eyck painted them to portray the sorrow of their sin or the state of the world around them. Furthermore, both figures have been painted in a highly naturalistic manner.

The panels next to Adam and Eve both depict a musical theme, each one with a choir of angels. To the left, which is the panel to the right of Adam, is a group of eight angels standing behind a wooden lectern with a metal adjustment in the center, we will notice the angel closest to it holding this adjustment with his left hand.

The angels all appear to be singing, although each one has a unique facial expression that denotes confusion, concentration, or disinterest, angelic attributes we would not expect from history paintings. Furthermore, scholarly sources have also described them as “unidealized” because of their humanized facial expressions and because they do not have wings.

The panel to the far right, which is the panel to the left of Eve, also depicts these “unidealized” angels, only here there appears to be six, moving further into the distance, and quite cramped into the pictorial space that we can only see part of the head of the angel to the back. The angel in the front is in full view, seated and playing the organ, with two standing angels each holding stringed instruments.

There are three central panels depicting three figures, this arrangement is also referred to as the Deësis; the left is the Virgin Mary, her head is downward with a book in her hands, the central figure is either Jesus Christ or God, who is staring directly at us, the viewers, his right hand is raised in the gesture of a blessing, and to the right is John the Baptist, his right index finger is lifted and he is gazing in the direction of the Christ figure in the center, there is also a book on his lap.

All three figures are lavishly depicted in drapery and bejeweled, surrounded by gilded backgrounds with various inscriptions. At Jesus Christ’s feet is a crown on what appears to be a lower step, of which we see some inscriptions too.

The Opened View: Lower Register

The lower register consists of five panels, which appear almost as one image, depicting a vast green landscape with several groups of people in each. The central panel, however, is one large painting with two smaller paintings next to it on either side.

The narrative in the central panel is from the Gospel of John from the Holy Bible, depicting the Lamb of God on an altar, with fourteen angels around it.

The angels are also holding various symbols related to Jesus Christ’s crucifixion, otherwise also referred to as the “Instruments of the Passion”, namely the angels to the left are holding the crown of thorns and the cross, and to the right, the angels hold the pillar of flagellation with the whip. There are also four larger groups of people surrounding this group, each placed towards the corners of the painting.

The lamb on the altar is standing on all fours facing us, the viewers, while there is a strong stream of blood pouring into a chalice from an open wound on the lamb’s chest. The lamb represents Jesus Christ as the Savior. If we look at the two panels to the left of the central painting, we will see they are grouped into what has been described as warriors and judges, otherwise known as the “Just Judges” comprising “administrators” and “politicians” and the “Knights of Christ”, most of them are on horses.

The two panels to the right depict groups of men, and some women, who have been described as pilgrims and hermits.

The Closed View

If we look at the closed view in more detail, there are four lunettes along the upper part depicting prophets and oracles, namely, from the left is the Prophet Zacharias, it is the Erythraean Sybil, Cumaean Sybil, and then the Prophet Michah.

The scene directly below this is larger, depicting the Archangel Gabriel to the left and the Virgin Mary on the right; the narrative here is the Annunciation to Mary.

There is an open space between these two figures, showing the room they are both standing in. We can also view an outer landscape here of an urban environment, which van Eyck depicted with skillful detailing. Some scholarly sources suggest this is a view of Ghent, however, some suggest it is not.

There are four figures on the lower panels, which include the figures of the donors, as mentioned above, on either side. Between these two panels are two other panels depicting the grisaille paintings of John the Baptist and John the Evangelist.

Color, Light, and Texture

Jan van Eyck innovatively utilized oil paints, becoming known for his skillful application of oil paints. He applied oils to enhance colors on the painting, alongside glazes, which also gave the painting its light and luster and the characteristic realism, unlike many Northern Renaissance paintings.

There are numerous examples here in the Ghent Altarpiece, specifically the crown and jewelry we see in the upper register by the central figure of Christ, the various crowns atop the Angels’ heads, as well as the slight shine on the tiles below Christ’s feet.

Furthermore, van Eyck delicately depicted light and shadow. If we look at the closed view, it has been described as “soft” in appearance, with the light source from the windows and possibly another unknown light source beyond our view.

If we look at the open view, the central panel, which depicts the Lamb of God, the central light source emanates from the Sun above with visible rays depicted as thin golden beams. There are also various shadows at play here, for example, the shadowing that falls faintly on the water’s surface as it ripples from the fountain.

Conversely, there are no shadows depicted where the Angels are kneeling near the Lamb.

Scholarly debates about the meaning of this have pointed to the Biblical passage from the Book of Revelations, 21:23, “And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, because the glory of God illuminates the city, and the Lamb is it its lamp”.

Space, Perspective, and Scale

Jan van Eyck masterfully utilized space in the Ghent Altarpiece, for example, if we look at the closed view and the figure of Adam to the left, his right foot protrudes seemingly out of the painting’s frame giving it a three-dimensionality, as if the painting of Adam is indeed a real sculpture.

Furthermore, it is van Eyck’s detailing in the entire composition, which gives it its three-dimensionality. There are also several types of perspectives van Eyck depicts here.

On the upper register, we see mostly frontal and level views of the figures whereas on the lower register van Eyck depicts the landscape from an aerial view as if we are slightly looking from a heightened vantage point over the Lamb and the landscape. The Ghent Altarpiece measures around 5.2 x 3.75 meters, and the closed view is around 375 x 260 centimeters.

Each panel has its own measurements, but overall, the altarpiece is almost life-sized and gives a spectacular visual composition, not only for modern-day visitors but for its time as well.

An Ongoing Restoration Project

The Ghent Altarpiece restoration has been ongoing with numerous attempts over the years to quell the damages from its handling and exposure to the external environment, some of the cleaning attempts worsened the altarpiece.

A large restoration project started in October 2012 and was completed in 2020 by the Museum of Fine Arts in Ghent under the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage; the budget was €2.2 million.

During this restoration, visitors were able to view the process only with a glass casing between them. There were several discoveries from the Ghent Altarpiece restoration project, most notably the Lamb of God’s facial features. Its ears were repainted, higher than where it originally was; its eyes were painted over and replaced to the sides of its face compared to the original placement that was more centralized on its face, and its original nose and mouth were also more distinct.

The result of the Ghent Altarpiece restoration revealed the original masterpiece the striking features of the Lamb of God led many to voice its almost full-frontal gaze, it has also been described as having “humanoid” features.

Reportedly, almost 70% of the altarpiece was painted over and varnished during the years, there were also layers of dirt, all of which undoubtedly hid many of the original features, including the Lamb of God, but this was not the only detailing that was covered up.

Other examples include the visible veins on the painted sculptures on the outer panels, cobwebs behind the figure of Lysbette Borluut, and the architectural and landscape features. The uncovered detailing from the “Ghent Altarpiece” restoration project revealed the immense attention to detail in which van Eyck painted.

The Ghent Altarpiece: A Masterpiece of Reality and the Sacred

The Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck astounds visiting viewers to this day from all over the world. It is now housed in Saint Bavo’s Cathedral, stored in a bullet-proof glass case standing at twenty feet. When the Ghent Altarpiece was first made it was only opened on specific occasions like Mass for the Eucharist, and it would have been placed on the altar in the cathedral, as sources describe it would have been “ritually opened” and not remain open throughout the year, therefore, churchgoers would also see the closed view most of the time.

In this article, we presented only a fraction of what the “Ghent Altarpiece” is as a polyptych from the Northern Renaissance era. There are numerous symbolisms and motifs that make this a true treasure of its time, and understandably the “most coveted” painting in history. Van Eyck painted in such a detailed manner and incorporated a realism that was wholly different from religious paintings of the time, which focused on idealistic imagery. We can see the hairs on Adam’s legs, the craters in the moon, the reflection of the window on the blue brooch of one of the Angels, the pincers and the tongue held by one of the martyrs, but there is still so much more to discover. We encourage you to dig in further and find these hidden treasures (look out for the hidden faces painted on one of the panels) that ultimately make the “Ghent Altarpiece” a masterpiece of reality and the sacred.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted the Ghent Altarpiece?

The Ghent Altarpiece (c. 1425 – 1432) was painted by the Flemish artist Jan van Eyck. Scholarly sources also state that Jan’s brother, Hubert van Eyck, started the altarpiece and completed the underpaintings. However, he died in 1426 and it was left to Jan van Eyck to complete.

Where Is the Ghent Altarpiece Housed?

The Ghent Altarpiece is housed in Saint Bavo’s Cathedral in Ghent, Belgium. It was originally housed in the Vijd Chapel, which was the name of the commissioners of the polyptych, Jodocus Vijd, and his wife, Lysbette Borluut.

What Type of Painting Is the Ghent Altarpiece?

The Ghent Altarpiece is a polyptych panel painting, as it is composed of several panels that are joined. There are 24 panels collectively, and it folds open and closed. On the closed view there are 12 panels when counting the lunettes on the upper part, and on the open view, there are also 12 panels, divided into two registers or levels.

Who Commissioned the Ghent Altarpiece?

The Ghent Altarpiece was commissioned by the Jodocus Vijd and his wife, Lysbette Borluut. They were wealthy merchants and according to scholarly theories, their payment for the polyptych provided a way for them to atone for their wealth so to say, and to directly showcase the wealth they had.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck – Studying Jan van Eyck’s Iconic Work.” Art in Context. April 12, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/ghent-altarpiece/

Meyer, I. (2022, 12 April). Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck – Studying Jan van Eyck’s Iconic Work. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/ghent-altarpiece/

Meyer, Isabella. “Ghent Altarpiece by Jan van Eyck – Studying Jan van Eyck’s Iconic Work.” Art in Context, April 12, 2022. https://artincontext.org/ghent-altarpiece/.