Spanish Architecture – Exploring the Most Famous Architecture in Spain

Spanish architecture pertains to the architecture created by famous Spanish architects in Spain and across the world. The term refers to Spanish buildings that were built inside Spain’s existing borders prior to the country’s independence. Based on that particular era, the architecture of Spain displays a significant deal of geographical and cultural variation. Today, we will delve deeper into Spanish architecture history as well as examples of famous architecture in Spain.

What Is Spanish-Style Architecture?

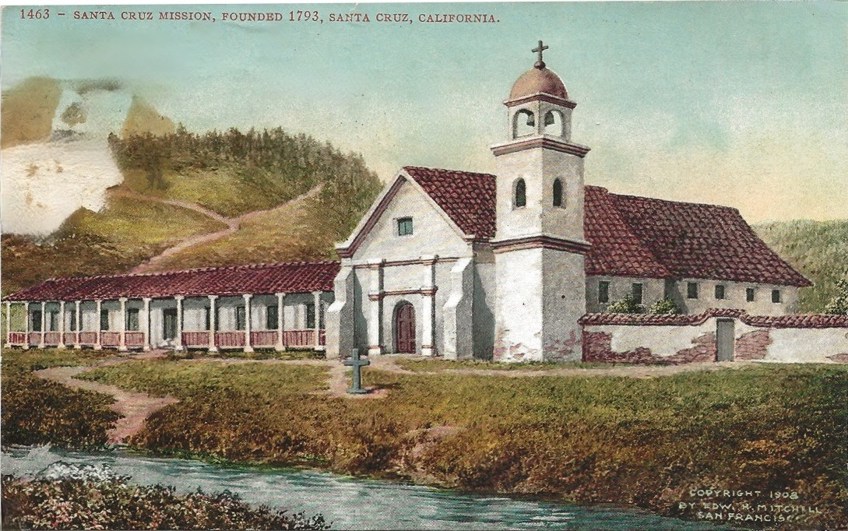

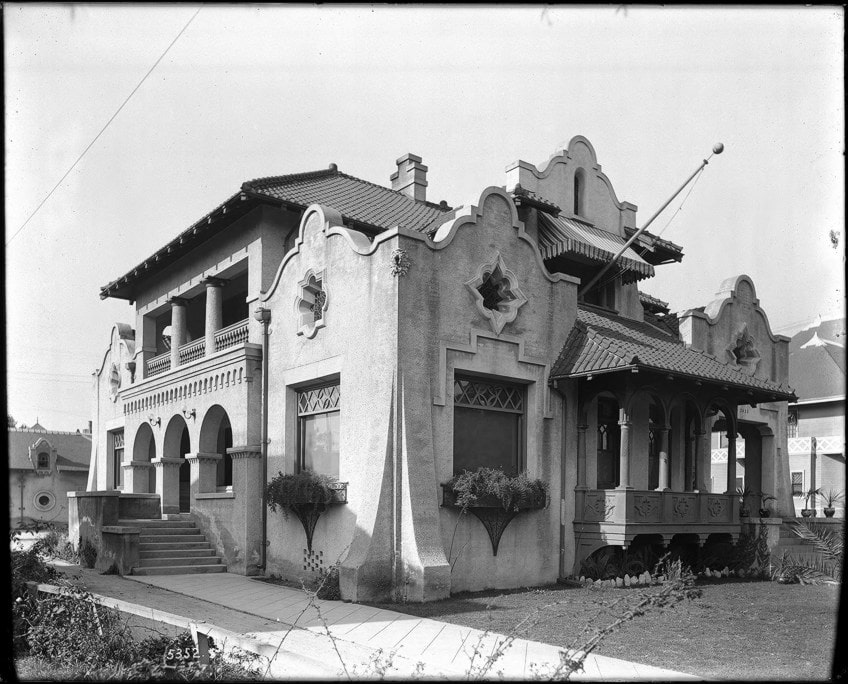

Spanish architecture has a roughly 400-year-long history and has been a prominent construction style for centuries. The architecture of Spain is recognized for its complex details, patterns, and grand structures. Spanish-style architecture was once limited to the gorgeous, elaborate churches built in the 1900s by Spanish missionaries before it was embraced by homeowners across North America.

Spanish Architecture History in North America

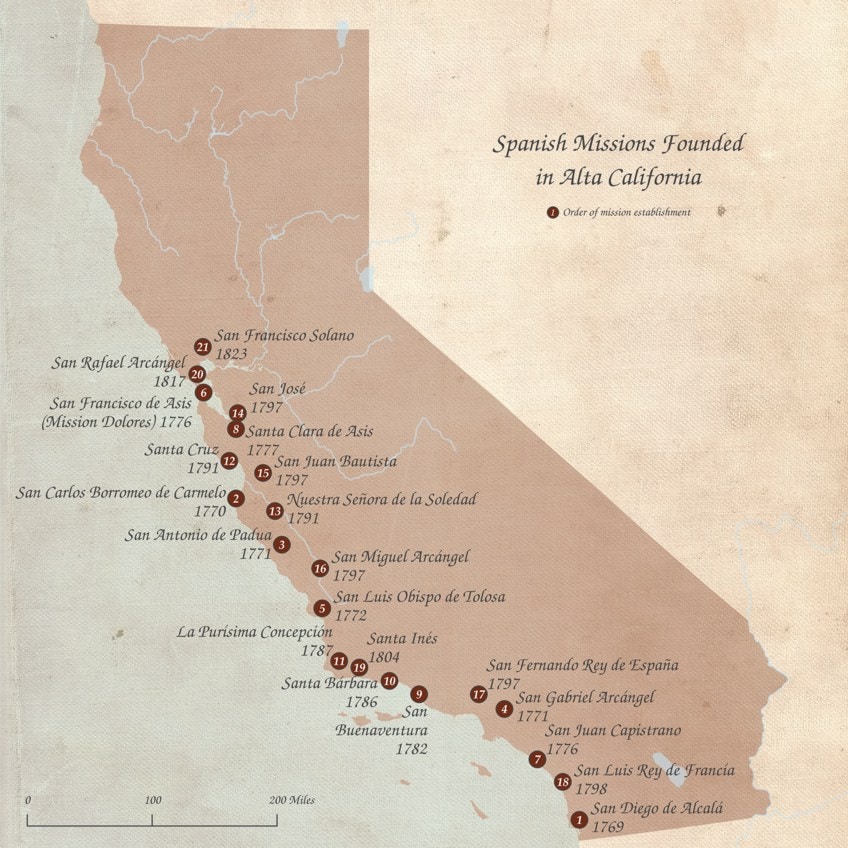

Between 1600 and the mid-1800s, when Spanish people began to come to the Americas, they carried with them classic Spanish construction designs. These colonists were able to apply conventional building methods since they constructed their homes in temperatures similar to those of Spain, such as California, Florida, and the Southwest.

Because Spanish architecture was influenced by Mexican and Indigenous traditions across the nation, the motifs of Spanish buildings in the Southwest and Southeast varied significantly.

Spanish-style architecture, like many other architectural forms, was significantly affected by the construction materials available at the time. The Spanish immigrants could employ straw and clay for inner and exterior surfaces, red clay for their signature red roof tiles, and wood for support beams and stunning exposed beams. Despite the fact that the Spanish Colonial era concluded in the mid-1800s, Spanish architectural methods and styles were more prominent. Two key events influenced the expansion of Spanish architecture:

- Ramona, an 1884 novel by Helen Hunt Jackson, was published. The story is about a little Indigenous girl growing up in California in the early 1900s. It thoroughly glorified the concept of California and completely enthralled the general population in the United States.

- California’s structure was erected as a classic Spanish missionary for the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago, where each state developed a structure to display things manufactured inside the state.

By the 1920s, there had been a significant increase in the number of residences erected in Spanish mission architecture. It’s still a popular architectural design today, especially in the United States’ warmer, drier climes.

A History of Spanish Architecture Styles

Although certain Spanish buildings are distinctive, the architecture of Spain developed along the same lines as other architectural styles from across the Mediterranean and Northern Europe. The emergence of the Romans, who left behind some of their more impressive structures in Hispania, marked a significant change.

Countless historical examples of famous architecture in Spain demonstrate the country’s capacity to conserve and cherish architecture.

Prehistoric Spanish Architecture

Burial chambers from 4000 BC are the earliest evidence of Spanish building. Dolmens are constructions that were erected by the earliest humans who lived in the Iberian Peninsula. These dolmens were built of stone and resemble tables.

Visigoths and Celts who came to Spain from the north created the first instances of Spanish architecture. These locations were recognized to be pilgrimage and devotional destinations.

The Celts concentrated on fortified mountaintop settlements known as castros. Many of these Celt communities may be found in the Asturias and Galicia provinces. Archaeologists and scholars regard them as valuable sources of knowledge.

Roman-Style Architecture

The Roman invasion of Spain resulted in the Romanization of the Iberian Peninsula. During this time of Spanish architecture, communities were modified and the people were able to absorb the Roman empire’s culture and way of life.

Large cities like Cordoba and Tarragona facilitated urbanization by connecting usable buildings and commercial hubs with transportation infrastructures.

The architecture of the Roman empire in Spain is comparable to that of Greece and Italy, two regions where the empire prospered and flourished. Aqueducts, amphitheaters, Bridges, coliseums, and memorials are all manifestations of this era’s engineering ability. Roman structures such as La Coruña’s Tower of Hercules are still in use today.

Pre-Romanesque Architecture

Christian-influenced structures are referred to be pre-Romanesque Spanish architecture. Arches and lattices, immensely thick stone masonry, symmetrical buildings, big towers, Celtic-influenced medallions, columns, and iconographies like warriors and animals are all examples of this period’s innovations in design and structural features. The region of Asturias, particularly the city of Oviedo, is home to the bulk of Pre-Romanesque Spanish architecture.

The Ermita de Santa Cristina de Lena is a remarkable instance of well-preserved pre-Romanesque construction.

Romanesque Architecture

Spain was the second country to develop Romanesque architecture. The architecture featured symmetrical structures, thick walls, rounded archways, useful columns, and massive rounded towers, defined this time. Monks created the majority of the Romanesque monasteries, which had been constructed for religious purposes.

The beautiful parts of Roman architecture faded away, and architects focused on designing buildings that were utilitarian.

Mudéjar-Style Architecture

The Mudéjar style sprang from the clash of Islam and Christianity and was created by Moors who remained in Spain and did not convert to Christianity. Syria and Persia have influenced the style. Horseshoe arches with columns, complicated geometry, octagonal turrets, glossy tile mosaics, and stucco, timber, and brick construction are all notable features.

This architectural style can be seen in synagogues and mosques. Even after the Moors departed Spain, their architectural contributions may still be seen in current structures.

Gothic Architecture

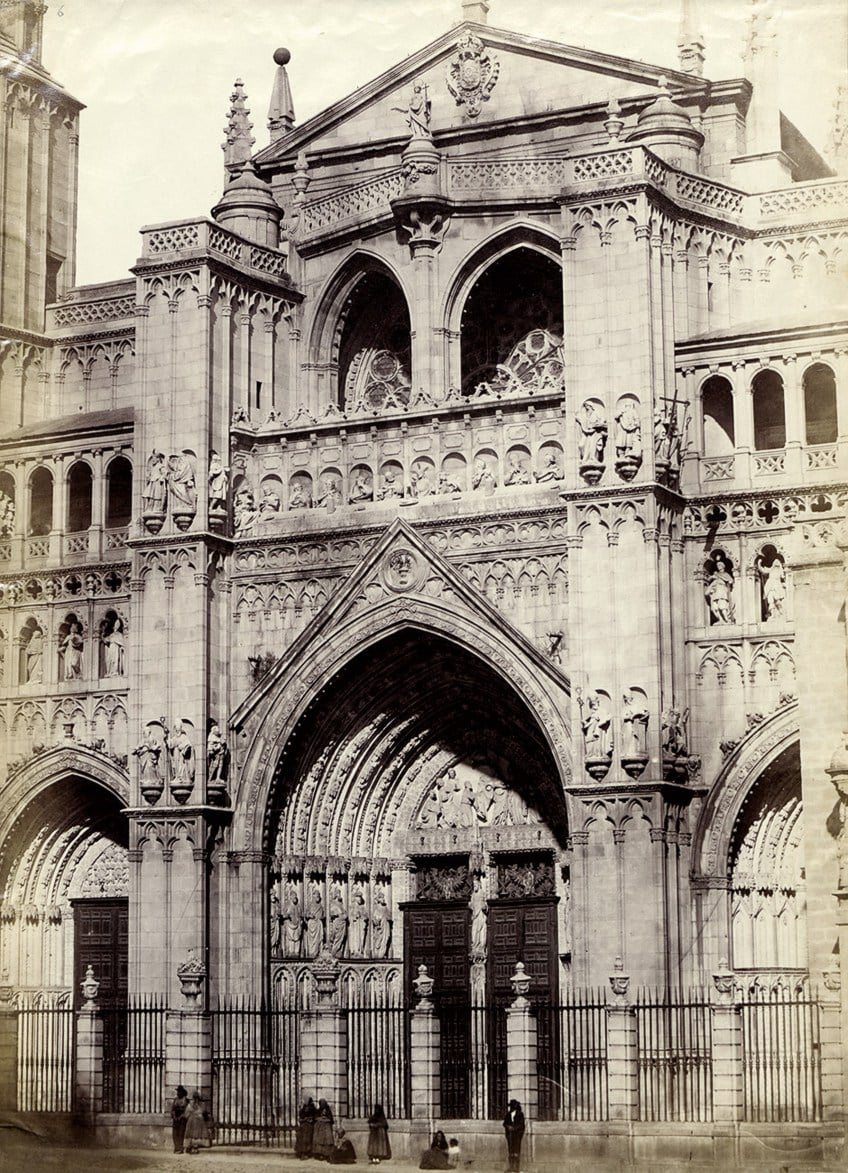

Following Mudéjar construction, the Gothic style combined European and Romanesque methods. Pointed archways, stained glass, thin walls, gargoyles, ceilings, and clusters of slender columns are all typical features. During the 13th century, when it was known as High Gothic, the style flourished. For Spain, it symbolized growth and ingenuity.

During the Middle Ages, the Catholic church embraced the Gothic style, and numerous churches from this era had a lightness to them. Gothic churches, on the other hand, are massive structures with incredible engineering.

Cistercian Architecture

Cistercian Spanish architecture is a style that emerged between the Romanesque and Gothic periods. It’s commonly seen in monasteries in remote areas. It combines features of Romanesque and Gothic Spanish architecture with a basic design and little decoration.

Because they didn’t desire a luxurious existence, dissident monks introduced this design style to Spain. They thought it diverted Christians’ attention away from the church’s mission.

Renaissance-Style Architecture

Gothic structures were altered to fit the criteria of the new Renaissance style at the start of the Renaissance period. Famous Spanish architects started to embrace the style, which had Italian influences and was frequently blended with Gothic heritage and regional idioms.

This fusion resulted in the Plateresco style, which featured grandiose facades and highly wrought silver work.

Highly ornamented facades, classical Roman style, symmetrical embellishment, and Christian symbols such as statues are all common features of Renaissance Spanish architecture. The Gothic style started to diminish late in this period, and the best specimens of Renaissance architecture, such as the Palacio de Carlos V at La Alhambra, began to flourish.

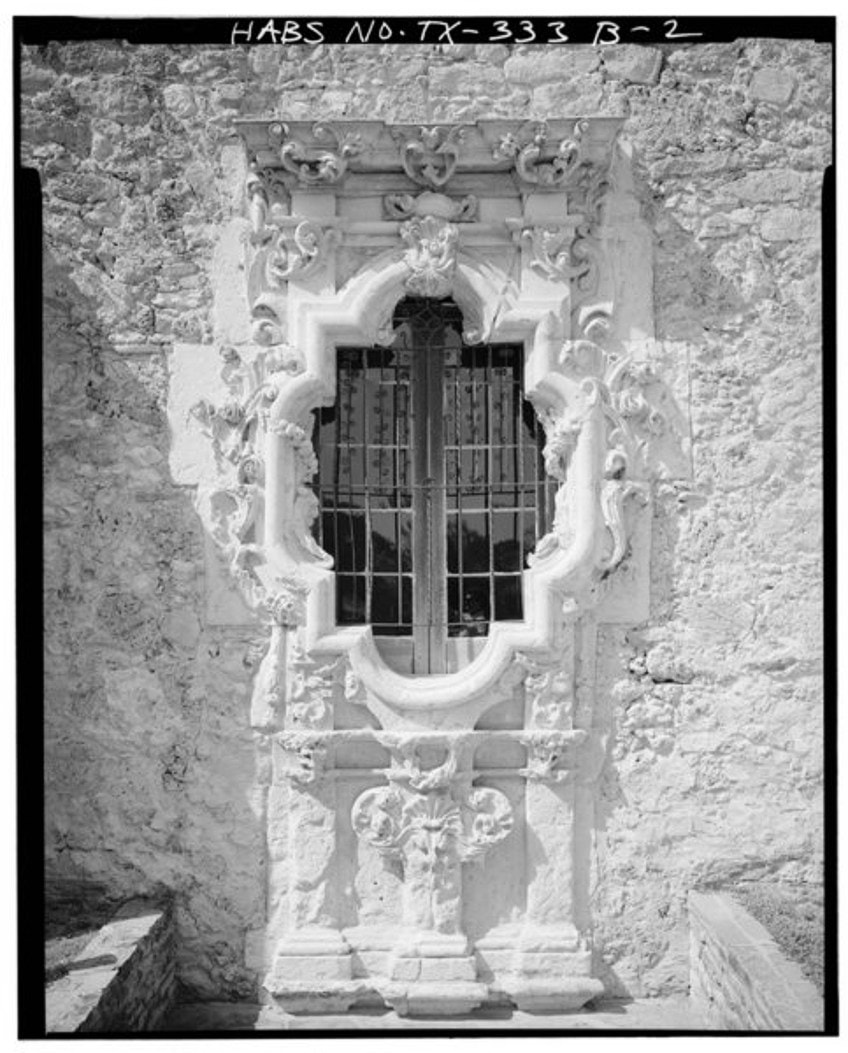

Baroque Architecture

The Baroque style, like Renaissance architecture, was influenced by Italian influences. It was influenced by the French Rococo style and had distinct characteristics that set it apart from other styles. With rich use of stone, brick, and metal, Baroque Spanish architecture emphasizes decorated facades, excessive florid details, and complex sculptural decorations.

The Baroque style developed further.

The Churriguera family disliked the conventional Baroque style and turned it into the Churrigueresque style, which is an ornate, exaggerated, and showy type of decorating. This type of Baroque may be seen all across Salamanca, where Churrigueresque architecture flourished to its full potential.

Neoclassical Architecture

The architecture of the Neoclassical style is both technical and philosophical. San Fernando’s Royal Academy of Fine Arts was the first to promote it. Neoclassical architecture, like other Spanish architectural forms, came from Italy as the current go-to design style. The emphasis was on harmony and minimalism. The design features are practical, efficient, and have a Roman influence.

If you visit Spain, you’ll notice Neoclassical architecture at museums and modern buildings such as the Museo del Prado in Madrid.

Eclecticism and Modernism

Eclecticism and Modernism are a mix of earlier Spanish architectural styles. New materials like iron and glass began to appear in architecture with the introduction of the industrial revolution, leading to new revival versions of earlier conventional forms.

Eclecticism, a new movement in Spain, allowed architects to pick their style based on the aim of their work.

In Catalonia, a new style known as Modernism began to emerge at the same time as Eclecticism. Architect Anton Gaudí employs minimalist, industrial, and organic aspects to create magnificent structures in Barcelona and other Catalan cities.

Characteristics of Spanish Architecture

As previously indicated, Spanish missions have distinct qualities dependent on the aesthetic tastes of the founding priest. However, there are several commonalities across Spanish missions around places like North America.

We shall now examine a few of the key characteristics of Spanish-style art.

Stucco White Walls

Not only was adobe (a mix of clay and water) an outstanding and plentiful building material for Spanish immigrants, but it also provided some shelter from hot, sunny days when finished with white stucco. The following is how it works: thick plaster walls keep cold air throughout the day and prohibit it from leaking to the outside; at night, when temperatures drop, the warmth gathered during the day is let back into the residence.

Clay Red Roof Tiles

Clay red roof tiles, another structural material that emerged from its potential availability, are among the most prominent features of Spanish-style architecture. The clay tiles, which were created similar in form to the half of a tube, were able to trap and hold cold air. Low, gently sloped roofs with eaves that extended over the roofline were common.

This provided additional weather protection.

Facades With Asymmetrical Towers

Asymmetrical facades were common in Spanish mission architecture, which was unlike that of the usual Spanish Colonial architecture. The construction was usually flanked by large square pillars and bell towers.

Arched Corridors

Decorative archways were common in the cloisters, or covered passageways, of Spanish missions. The archways might be decorated with hand-made tiles, various stones, or mosaic glass, but the walls were usually adobe and stucco.

Quatrefoil Windows

These windows, which resemble a four-petaled flower or a four-leaf clover, were prevalent in Spanish missions. Many modern Spanish-style homes use quatrefoil to provide a decorative feature to an otherwise plain exterior.

Famous Architecture in Spain

Spain is host to some of the most stunning buildings in Europe. Given the Iberian country’s rich culture and history, this comes as no surprise. Its monuments and structures are distinctive and distinct, and some are even designated as historical monuments that are internationally recognized.

Santiago de Compostela Cathedral (Galicia, Spain)

| Date Completed | 1211 |

| Architect | Fernando de Casas Novoa (1670 – 1750) |

| Function | Cathedral |

| Location | Galicia, Spain |

A tomb excavated in Padrón in 813 CE was supposed to have been divinely unveiled to be that of the apostle St. James, who was crucified in Jerusalem about 44 CE. His remains had been transported to Spain, where he had previously evangelized, according to tradition. The discovery of the relics gave Christian Spain, which was then restricted to a tiny band of the northern Iberian Peninsula, a rallying point.

After Alfonso II of Asturias constructed a church over the grave, which Alfonso III renovated with a bigger edifice, the town that sprang up around it became the most significant Christian pilgrimage site after Jerusalem and Rome throughout the Middle Ages.

The current cathedral was built by decree of Alfonso VI of Leon and Castile in 1078.

This Romanesque structure at the east end of Plaza del Obradoiro features a Baroque west facade designed by Fernando Casas y Novoa. The Pórtico de la Gloria, a tripartite porch placed below the front and displaying the Last Judgment sculpture by Maestro Mateo.

This piece is Romanesque but tinted with Gothic elements and is an exceptional highlight of the interior.

Founded in the 10th century was the monastery, which was then renovated in the 17th century. It is believed that St. Francis of Assisi constructed the monastery during a visit to Santiago in 1214. The Church of Santa Maria Salomé dates from the 12th century, with a subsequent facade.

Alhambra (Granada, Spain)

| Date Completed | 1238 |

| Architect | Pavel Notbeck (1824 – 1877) |

| Function | Cathedral |

| Location | Granada, Spain |

The Alhambra is located in an area of exceptional natural beauty. It was erected on a terrace that overlooks the Albaicin section of Granada’s Moorish old city. The Darro River runs through a steep ravine to the north near the plateau’s foot. The Moors planted roses, oranges, and myrtles in the park outside the palace. Its most distinctive feature is the thick timber of elms introduced there in 1812 by the Duke of Wellington in the Peninsular War.

The Puerta de las Granadas, a large triumphal arch originating from the 16th century, serves as the park’s lower entrance.

A big reflecting pond placed on the marble pavement is located in the center. The pond’s vibrant green and the trimmed myrtles blooming around its edges stand out against the white marble of the adjacent courtyard. The Alhambra was erected mostly between 1238 and 1358, during the reigns of Ibn al-Amar, father of the Nasrid dynasty, and his heirs, on a plateau overlooking the city of Granada. Yusuf I is credited with the magnificent interior decorations.

Following the ejection of the Moors in 1492, most of the interior was destroyed or destroyed, and the furniture was wrecked or taken.

Plaza de España (Sevilla, Spain)

| Date Completed | 1928 |

| Architect | Aníbal González Álvarez-Ossorio (1876 – 1929) |

| Function | Plaza |

| Location | Sevilla, Spain |

The enormous Plaza de Espaa is Seville’s most iconic plaza. Numerous buildings were built in and around Maria-Luisa Park for the 1929 Ibero-American Exhibition. This 200-meter-long Spanish square was designed by Anibal González in the Spanish Renaissance design.

Spain’s goal with the show was to create metaphorical peace with its former American territory.

Plaza de España is a semi-circle encircled by a row of structures that are mostly utilized as government facilities nowadays. On the square’s sides, there are two large buildings. The 52 seats and tile mosaics at the foot of the structure on the Spanish square are noteworthy.

Other features of the square are the big fountain in the center and the circular canal with its numerous attractive bridges. You may also hire a boat and navigate the waterways.

Guggenheim Museum (Bilbao, Spain)

| Date Completed | 1997 |

| Architect | Frank Gehry (1929 – Present) |

| Function | Museum |

| Location | Bilbao, Spain |

The Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao, Spain is a mix of complex, whirling shapes and compelling materials that respond to a sophisticated plan and industrial urban surroundings. Frank Gehry’s Guggenheim Museum, including over a hundred presentations and over ten million guests, not only changed the way designers and individuals think about museums but also boosted the economy of Bilbao.

In actuality, the “Bilbao Effect” is the phenomenon of a city’s transformation after the building of a magnificent piece of architecture.

The Basque government then requested that the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation assists in the creation of a Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao’s crumbling port sector, which was formerly the city’s main source of riches, in 1991. The famous museum was also part of a larger rehabilitation project aiming at rejuvenating and revitalizing the industrial town, which was regarded as rather suitable.

Almost immediately after its 1997 debut, the Guggenheim Bilbao became a major tourist destination, attracting tourists from all over the world. The riverfront location is on the northern outskirts of the city core. To the south is a road and metro, and to the eastern side is the Salve Bridge.

The structure circles and extrudes around the Salve Bridge, generating a curving riverbank walkway, creating a real physical link with the city.

The structure references landscapes, which can be seen in the gorge-like, tight corridor that leads to the main entry hall, or in the curving promenade and water elements created as a response to the Nervión River.

Although the tower’s metallic design seems almost floral from above, the bottom of the structure clearly resembles a boat, evoking Bilbao’s ancient industrial operations.

Externally, the seemingly haphazard forms of limestone, titanium, and glass are supposed to collect sunlight and react to weather and sunshine. Fixing clips create a small center depression in each of the titanium tiles, causing the surface to ripple in the shifting light and giving the overall composition an exceptional iridescence.

In this article, we have looked at the amazing architecture of Spain. Although certain Spanish structures are distinctive, Spanish architecture evolved in the same way as other architectural styles from the Mediterranean and Northern Europe. The arrival of the Romans, who left some of their most beautiful constructions in Hispania, signaled a tremendous shift. Numerous historical examples of notable architecture in Spain show the country’s ability to retain and respect architecture.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Spanish Architecture Come to America?

Spanish settlers in North America blended their building practices with other European and Native American elements to produce a wide range of styles ranging from mission to Spanish Colonial to the Mediterranean. While no two missions were the same, the founding priests created sanctuaries that were filled with natural light and incorporated Native American, Spanish, and Mexican influences. Mission-style residences, which were most fashionable between 1895 and 1910, had solid walls and conservatively-sized window sizes, plaster interiors, and bare wood beam ceilings to mirror the basic, rustic character of the churches.

How Did Spanish-Style Architecture Become Popular in America?

The popularity of the design may be traced back to two historical events that occurred during the period. The success of Helen Hunt Jackson’s 1884 novel Ramona, glamorized the tale of a young Indian girl in early 19th-century Southern California, creating an impression of Southern California as a Mediterranean paradise. The second effect was the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago when each state created structures to display items from their states. A. Page Brown, the architect of the California pavilion, constructed a building utilizing various features of California missions, and the form swept across the nation.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Spanish Architecture – Exploring the Most Famous Architecture in Spain.” Art in Context. June 13, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/spanish-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 13 June). Spanish Architecture – Exploring the Most Famous Architecture in Spain. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/spanish-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Spanish Architecture – Exploring the Most Famous Architecture in Spain.” Art in Context, June 13, 2022. https://artincontext.org/spanish-architecture/.