Rococo Architecture – Exploring the Rococo Era and Its Style

The Rococo style, often termed the Late Baroque style, is a dramatic and extravagant design aesthetic. Rococo architecture is most commonly associated with buildings built during the 18th century in France, but the style also impacted the arts, music, furniture design, and even tableware. However, in comparison to other artistic revolutions, Rococo characteristics were only prevalent for a short period of time.

Rococo Architecture

By the turn of the century, French Rococo architecture had fallen out of favor in the region. Nonetheless, Rococo architecture’s flowing curves, vivid palettes, and graceful asymmetry expanded rapidly throughout Europe and then beyond. First off though, let us start with an introduction to the Rococo era, as well as a Rococo definition!

Rococo Definition and History

The name “rococo” was coined as a humorous version of the French word rocaille, which referred to the use of small pebbles and seashells as decoration in decoration and grottoes, that had been fashionable since the Renaissance.

Rococo emerged in Paris, France during the 1730s as a reaction against Style Louis XIV, a geometrical style that reflected numerous classical elements. Rococo was far more frivolous and extravagant.

Rococo is ornate and full of gilded furniture like armchairs, tables, and trunks. Germain Boffrand, the designer of the Hôtel de Soubise, rose to prominence as one of France’s foremost Rococo architects. Rococo’s showy appeal served as a symbol of style and luxury throughout Europe, especially Austria, Bavaria, and metropolitan towns such as Rome, Saint Petersburg, and Munich.

The rococo style began in a more secular context, with Rococo-inspired embellishments employed to adorn entertainment salons. Rococo characteristics soon spread to more spiritual structures, significantly influencing churches created during this period in Portugal and South America.

Rococo buildings became less popular by the end of the 18th century. The extravagance of the Rococo era and Baroque art forms was criticized by French intellectuals such as designer Jacques-François Blondel and playwright Voltaire.

Neoclassicism arose in response to the Rococo style. Neoclassical forms are characterized by symmetrical columns, structures, and objects. Rococo houses had gone out of fashion by the 19th century, but its influence lives on: more contemporary constructions like New York City’s Grand Central Station and Woolworth Building, and both embody the splendor that typified the Rococo era.

Rococo vs. Baroque

One can find several distinct differences between the Rococo and the Baroque style. We have created a concise list to help differentiate the two. The following would be examples of Rococo characteristics that are not seen in the Baroque style.

- Similar to Art Nouveau, there is a partial abandoning of uniformity, with everything consisting of elegant curves and lines.

- A large number of C-shaped volutes as well as asymmetrical curves.

- The widespread use of flowers as adornment, such as flower festoons.

- The use of Japanese and Chinese motifs increased dramatically.

- Warm-toned pastel colors were predominantly used.

Rococo Characteristics

Which Rococo characteristics best define the style? Symmetry and a sense of awe play a large part in Rococo architecture. Here is a list of characteristics that help describe the style of Rococo buildings.

- The frilly style of Rococo, with snaking curves, twists, and ripples, was a welcome change from the neat lines of the French classicism style.

- Rococo interiors astonish and amaze in salons, mansions, churches, and other large residences. A magnificent staircase may become the focal point of a space, and a ceiling mural with cherubs might be a discussion opener for guests.

- Stucco was a popular material in the Rococo era. Stucco might be shaped and designed to astound the spectator.

- Another important aspect of the Rococo style was the brilliance of pastel hues. This palette might include pearly grays, creamy tones, soft yellows, pastel blues, and lilacs, among other powdered colors.

- Asymmetrical embellishments were used about everything from trimmings to joinery inserts for furniture items in Rococo. Asymmetrical patterns might feature shells or leaves.

- Wildlife elements appeared often in paintings and sculptures of the Rococo era. Rococo designs frequently include birds, florals, and fruits.

- Trompe l’oeil, which translates as “deceive the eye,” was a common artistic trick used in Rococo works. Trompe l’oeil introduced perspective to fine art, implying depth in two-dimensional works or generating the appearance of movement in motionless works.

- Rococo buildings’ exteriors are frequently modest, but their interiors are completely dominated by their adornment. The style was very dramatic, with the goal of impressing and awing the viewer at first glance.

- Church floor layouts were frequently complicated. They had interconnecting ovals and magnificent stairs which became centerpieces in castles, offering numerous viewpoints of the décor.

- The style frequently used art, molded stucco, fine woodworking, as well as illusionist overhead frescoes. These were intended to create the sensation that visitors entering the Rococo house were gazing up into the sky, while cherubs and other characters looked down on them.

Famous Examples of Rococo Architecture

The term “Rococo” refers to a style of architecture that emerged in France in the mid-1700s. It is distinguished by delicate yet robust decoration. Rococo ornamental arts existed for a brief period before Neoclassicism conquered the Western world, and are often categorized simply as “Late Baroque.”

Here are a few examples of famous Rococo houses and buildings that exemplify the Rococo definition of architecture.

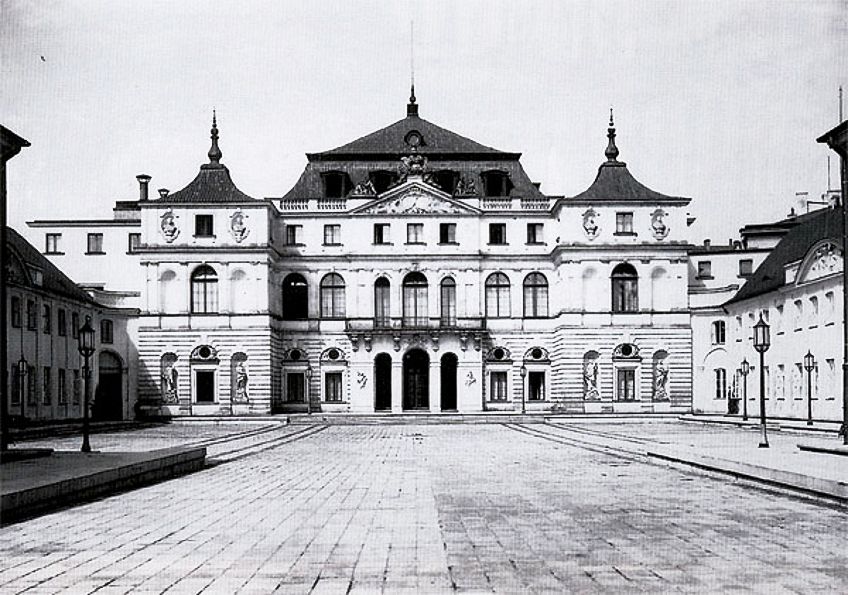

Brühl Palace – Warsaw, Poland

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Architect | Joachim Daniel von Jauch (1688 – 1754) |

| Year Completed | 1642 |

| Function | Palace |

Lorenzo de Sent designed the Rococo-style residence for Crown Grand Chancellor Jerzy Ossoliski between 1639 and 1642. It was designed as an extended rectangle with two hexagonal turrets on the garden side. The palace was embellished with sculptures, including an emblem of Poland above the main doorway, four images of Polish rulers in niches, and a statue of Minerva above the roof.

Bonifaz Wohlmut’s renovation of Belvedere in Prague, 1557–1563, may have served as inspiration for the palace’s top pavilion and its distinctive roof. Heinrich von Brühl purchased the palace as a house in 1750.

Joachim Daniel von Jauch’s ideas were used to rebuild it between 1754 and 1759. The palace was renovated and given a mansard roof. Two structures were constructed to the palace complex, which surrounded a triangular courtyard that was used as a parade ground at times. The palace was renamed the Brühl Palace at the time.

On May 27, 1787, the Palace was central to a scheme hatched by Russia’s envoy to Poland, Otto Magnus von Stackelberg. He disrupted yet another Polish policy that appeared to pose a danger to Russia. With few major conflicts in recent decades, the Commonwealth’s economy was prospering, and its budget had a significant surplus. Many people advocated for the money to be used on expanding the Polish army and purchasing new weaponry.

Nonetheless, because a big Polish military may represent a threat to Russian garrisons seeking to rule Poland, von Stackelberg urged his Permanent Council proxies to divert the funds to a new purpose. For a substantial sum of 1 million zlotys, the Council purchased the Brühl Castle and immediately decided to donate it to ‘Poland’s allied nation,’ Russia, to utilize as Russia’s new embassy.

Dominik Merlini gave the inside a neoclassical style at the end of the 18th century. During the years 1932 until 1937, the palace was converted into the new Polish Republic’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. This time, the architect was Bohdan Pniewski, who created a new contemporary building and updated the interiors of all of the palace complex’s structures.

On the 18th of December, 1944, the Germans intentionally and utterly demolished it.

Around 2008, the Warsaw local government planned to renovate the Brühl Palace. The rebuilt structure was supposed to have a facade referencing its original design, but a new independent investor may change the interiors to the demands of either an office or a hotel.

Charlottenburg Palace – Berlin, Germany

| Location | Berlin, Germany |

| Architect | Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff (unknown) |

| Year Completed | 1699 |

| Function | Palace |

Corinthian pillars were used to embellish the façade. On the roof was a cornice with sculptures. At the back of the palace, in the center, were two circular rooms, the higher one serving as a formal hall and the lower as an entrance to the gardens. Andreas Schlüter completed the palace after Nering died during construction.

On the 11th of July, 1699, on Frederick’s 42nd birthday, the palace was inaugurated. In 1701, Friedrich was crowned King Friedrich I of Prussia.

He had chosen Johann Friedrich von Eosander as royal architect two years before and ordered him to investigate architectural trends in Italy and France, notably the Palace of Versailles. When Eosander returned in 1702, he proceeded to expand the palace, beginning with two side wings to enclose a wide courtyard, and the central palace was enlarged on both sides.

In 1705 Sophie Charlotte died, and Friedrich named the castle and grounds Charlottenburg after her. The Orangery was erected to the west of the palace in the years that followed, and the central section was expanded with a massive domed tower and a wider vestibule. Andreas Heidt created a wind vane on top of the structure in the shape of a gilded figure of Fortune. The Orangery was initially used to store uncommon plants throughout the winter.

Throughout the summer months, when over 500 citrus and orange trees filled the baroque garden, the Orangery provided a beautiful setting for courtly celebrations. Various painters were asked to embellish the palace’s interior. As Friedrich I’s court painter, Jan Anthonie Coxie was commanded to create the walls and ceilings of the palace’s numerous chambers.

Between the period of 1701 and 1713, Coxie produced frescoes and an altarpiece inside the Palace Chapel, as well as artwork in the Gobelin Gallery and Porcelain Room. The frescoes in the Porcelain Hall were obvious propaganda celebrating Friedrich I’s illustrious reign.

When Friedrich I died in 1713, he was succeeded by his son, Friedrich Wilhelm I, whose development goals were less lofty, although he did ensure the structure’s proper preservation. Construction resumed after his son Friedrich II took to the throne in 1740. That year, stables for his private guard regiment were built to the south of the Orangery side, and work on the east wing began. The building of the additional wing was overseen by Georg Wenzeslaus von Knobelsdorff, the inspector of all Royal Palaces, who closely followed Eosander’s concept.

The outside was rather modest in design, but the inside decorations were lavish in art and sculpture, carpets, and mirrors.

The ground level was meant for Elisabeth Christine, who preferred Schönhausen Palace and only visited on occasion. Johann August Nahl was principally responsible for the top level’s exquisite décor, which included the Banqueting Hall, the White Hall, the Throne Room, and the Golden Gallery.

Amalienburg – Munich, Germany

| Location | Nymphenburg Palace Park, Munich |

| Architect | Joachim Dietrich (1690 – 1753) |

| Year Completed | 1739 |

| Function | Hunting Lodge |

The circular Hall of Mirrors in the heart of the structure takes up most of the ground level; its reflective surfaces reflect the park. Joachim Dietrich and Johann Baptist Zimmermann designed it. In the Bavarian national colors of blue and silver, it creates an ethereal mood.

The door to the Blue Cabinet and restroom, with accessibility to the privy room, is located to the south of the hall. The Rest Area served as the Electress’s bedroom, and the pavilion also houses an armory and kennels for the hunting hounds. The entrances to the Hunting Room as well as the Pheasant room are located north of the Hall of Mirrors. The Pheasant Room is located adjacent to the kitchen area.

The kitchen is ornamented with valuable Delft tiles that were jumbled up in the wrong sequence by employees while being placed.

The white and blue Chinese-style tiles depict blossoms and birds. The Castrol stove for the kitchenette is made of stone and has multiple fire holes capped by corrugated iron plates. It was the first model that totally covered the fire and was also referred to as a stew stove.

A plaster sculptural artwork by Johann Baptist Zimmermann depicts a hunting episode with the deity Diana on the eastern facade’s center niche. The display introduces the picture program in all of the Rococo building’s facilities.

The loft was derived from 1737 and was likewise made to Zimmermann’s design, with ornate vases that vanished at an unknown era. Hans Geiger restored and designed them in 1992: four decorate the entry facade and twelve decorate the yard side of the Amalienburg.

An elevated concealment for pheasant shooting was provided by a platform with decorative lattice attached to the structure in the center of the roof: the birds were led to the Amalienburg from the old pheasant building.

The Amalienburg lacks independent agricultural buildings in comparison to the other two park pavilions since the castle could be fed by the kitchens of Nymphenburg Palace.

Asamkirche – Munich, Germany

| Location | Munich, Germany |

| Architect | Egid Quirin Asam (1692 – 1750) |

| Year Completed | 1746 |

| Function | Church |

The church was erected as a personal church for the greater good and the redemption of the founders, rather than as a commission. As contract workers, this also permitted the Asam siblings to create in accordance with their ideals. Egid Quirin Asam, for instance, could view the altar via a window in his private residence close to the church. He also envisioned the church as a confessional church for young people.

As a result, the little church features seven confessionals featuring allegorical motifs.

The Sendlingerstraße residences are merged into the Baroque façade, which swings somewhat convex outwards. St. Johann Nepomuk was erected in a small area, measuring just 22 by 8 meters. Even more impressive is the craftsmanship of the two constructors, who were able to seamlessly blend building, painting, and sculpture in the two-story area.

The indirect illumination in the choir section is exceptionally nicely done: the Trinity figures are effectively lighted from behind, concealed behind the cornice window. The cornice itself appears to sway up and down due to its curved design. The interior is split vertically into three portions, with the brightness increasing from the bottom up.

The lowermost area of the seats, for church guests, is kept somewhat gloomy; its design represents the world’s suffering. The second part, positioned above, is white and blue in hue and is designated for the emperor.

God and eternity are commemorated in the topmost area of the distant and veiled lighted ceiling mural. The Asam Church’s high altar is flanked by four spiral columns. These columns are used at the high altar to pay homage to the four Bernini columns that stand above St. Peter’s tomb.

Previously, the Asam brothers studied at the Accademia di San Luca in Italy under Lorenzo Bernini. God, the Savior, is at the very top. A relic of John of Nepomuk is housed beneath the tabernacle. Ignaz Günther sculpted two angels that surround the gallery’s altar and were later added.

Due to its position as a private chapel, the Asamkirche differs from other more rigorously modeled Baroque buildings. The chapel altar is facing west rather than east, as is customary.

Furthermore, the crucifix facing the pulpit was abnormally low. It was hung above the pulpit in Baroque churches so that the preacher may look up to Christ Jesus. The choir was severely destroyed in a bombing raid in 1944. From 1975 to 1983, interior restoration was carried out in accordance with source research, with the goal of returning the choir to its supposed original look.

Braniki Palace – Warsaw, Poland

| Location | Warsaw, Poland |

| Architect | Johann Sigmund Deybel (c. 1685/1690 – 1752) |

| Year Completed | 1753 |

| Function | Palace |

The original structure that existed where the palace presently stands as a 17th-century home of the Sapieha family was bought by Stefan Mikoaj Branicki in the early 18th century. This led to the present palace, which was erected in 1740 for Hetman Jan Klemens Branicki by Johann Sigmund Deybel. French palaces influenced the now-rococo palace.

The layout was designed like a horseshoe, with a corps de logis in the center and two side wings.

The structure was placed away from the street by a symmetric courtyard set off in this manner, where the privileged guests entered. The façades were well-balanced with rococo design and rooftop windows. Jakub Fontana designed the interior in the rococo style. Later, a pavilion named “Buduar” was constructed at the back of the south wing.

The Branicki Palace was originally known as the Mrs. Krakowska Palace since the estate was inherited by Branicki’s lovely wife Izabella Poniatowska, sister of King Stanislaw August Poniatowski, following his death.

She hosted a salon at the palace and was recognized as a patron and prospector of artists, thinkers, and statesmen during Poland’s Enlightenment era. Shortly after, in 1804 the Branicki Palace was purchased by General Józef Niemojewski.

The mansion was renovated by the new owner, who commissioned architect Fryderyk Albert Lessel to construct two side outbuildings between 1804 and 1808. The Stanislaw Sotyk family lived at the palace beginning in 1817.

The mansion was severely damaged during WWII (it was burnt down in 1939 and devastated by the Germans throughout Poland’s Occupation), but it was totally reconstructed after the war. It was reconstructed in 1967, based on Bernardo Bellotto’s drawings, and presently accommodates Warsaw City Hall.

Catherine Palace – Saint Petersburg, Russia

| Location | Saint Petersburg, Russia |

| Architect | Francesco Bartolomeo Rastrelli (1700 – 1771) |

| Year Completed | 1756 |

| Function | Palace |

While Stasov’s Neoclassical interiors are excellent examples of late 18th- and early 19th-century style, Rastrelli’s enormous suite of formal rooms known as the Golden Enfilade is the palace’s most famous feature. It begins with the vast airy ballroom, the “Grand Hall” or “Hall of Lights,” with a beautiful painted ceiling, and continues with various differently adorned smaller rooms, including the reconstructed Amber Room.

The Great Hall is a formal apartment created by Bartolomeo Rastrelli in the Russian baroque style. The Great Hall was designed for larger gatherings such as dances, formal events, and masquerades.

The hall, which is around 1,000 square meters in size, was decorated in two hues. The windows on the palace’s eastern side face the park, while the windows on the palace’s western side face the palace plaza. In the evening, 696 bulbs illuminate a dozen chandeliers around the mirrors.

Rastrelli created the chamber in the mid-18th century. The modest room is lighted by four windows that face the formal courtyard. On the other wall, the architect installed fake windows with reflections and mirrored glass, rendering the hall more vast and cheerful. The hall is decorated in the traditional Baroque interior style, with gold wall carvings, intricate gilt pieces on the doors, and ornate patterns of stylized flowers.

The ceiling artwork was created by a well-known Russian School student from the mid-18th century. It is derived from the Ancient Greek tale of Helios, the sun god, and Eos, the lady of the dawn.

The White Formal Dining Room is located near the old Dining Room but on the other side of the Main Staircase. The empresses’ ceremonial dinners, or “evening meals,” were held in this hall. The sides of the dining hall were adorned with golden carvings to the highest degree of extravagance.

The furniture features golden inlays on the consoles. Some of the furniture in the room nowadays is original, while other items are copies. The Triumph of Apollo painting is a reproduction of an artwork by Guido Reni from the 16th century. The hall’s inlaid floors are made of valuable wood. The Alexander I Drawing Room was created between 1752 and 1756 and was part of the emperor’s private suite.

Because the walls were draped in Chinese silk, the drawing-room stands out from the majority of the palace’s formal chambers. The room’s other design was typical of the palace’s formal chambers, including a ceiling fresco and gilded embellishments.

Asian and Berlin porcelain are shown on the beautiful long tables and inlaid wooden commode. Ivan Martos’ plaster statues decorate the pistachio-colored walls of the space. The chamber was severely destroyed during the Great Fire in 1820. It was later repaired under Stasov’s supervision.

Christian’s Church – Copenhagen, Denmark

| Location | Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Architect | Nicolai Eigtved (1701 – 1754) |

| Year Completed | 1758 |

| Function | Church |

Christianshavn was built in 1617 by Christian IV as a town specifically for merchants, and a substantial population of German businessmen and artisans settled there. Despite the fact that Christianshavn had been integrated into Copenhagen before 1674, they did not attend St. Peter’s Church, as the rest of the city’s German community did, but instead gathered in the local Church of Our Savior.

This persisted until they ultimately requested permission from King Christian VI to establish their own church. The King accepted the designs and contributed significantly to the construction of a former saltern at the end of Strandgade in the southern portion of the neighborhood.

He also authorized the holding of a lottery to fund the project; the completed building was informally known as the Lottery Church. In exchange for his consent and giving of the property, the monarch established very stringent criteria for the location and style of the church. The king’s chosen architect at the time, Nicolai Eigtved, was charged with building the new church but died before it could be finished in 1754.

His son-in-law, Georg David Anthon, was tasked with overseeing the church’s construction, which was finished in 1759. Anthon also planned the spire, which was added in 1769. The church is rectangular, with the nave filling the area between the smaller instead of the longer sides, giving it extraordinary breadth. The church, which stands on a granite pedestal, is a yellow brick structure with sandstone finishes for the gateway and tower.

The doorway is adorned with Ionic pillars, and the round-arched panes are tall and thin. The tower stands 70 meters high. The spire was erected in 1769 by Eigtved’s son-in-law, D. G. Anthon. The tower lies in the center of the northern side, which serves as the primary front. It is 70 meters tall.

Christian’s Church has a unique interior design that is suggestive of a theater.

In addition to the seats on each side of the nave, three levels of balconies with boxes rise the whole height of the edifice on the north, west, and south sides. They are all situated to provide the crowd a good view of the platform on the eastern side, which resembles a stage.

The tall thin altarpiece, which includes not only the altar table but also the podium above it, and the organs at the very top, dominates the space.

The grand entrance, topped by the royal box, is on the west side, facing the altar and beneath the tower. In medieval fashion, the organ is placed in the incorporated altarpiece above a clock display. Hartvig Jochum Müller, a notable specialist at the time, developed the initial instrument in 1759. A new pneumatic instrument on Müller’s façade was erected in 1917, and the church’s organ, which is still used today, was constructed by P.-G. Andersen in 1976.

The Rococo style, often known as the Late Baroque style, is a theatrical and lavish design approach. Rococo architecture is most generally associated with buildings constructed in France during the 18th century, but the style influenced the arts, music, furniture design, and even tableware. In comparison to earlier aesthetic revolutions, however, Rococo traits were only dominant for a brief time. French Rococo architecture had gone out of popularity in the region by the turn of the century. Nonetheless, the flowing curves, vibrant colors, and elegant asymmetry of Rococo architecture spread fast throughout Europe and then beyond.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Are a Few Characteristics of Rococo Houses?

In Rococo, asymmetrical decorations were employed on everything from trims to joinery inserts for furniture. Shells or leaves were used in asymmetrical designs. The exteriors of Rococo houses are often modest, but their interiors are totally dominated by their ornamentation. The style was quite dramatic, with the purpose of immediately stunning and amazing the observer.

What Is the Difference Between Rococo and Baroque Style?

There are significant distinctions between Rococo and Baroque styles. There is a partial abandonment of homogeneity, similar to Art Nouveau, with everything consisting of graceful curves and lines. The Rococo style, often termed the Late Baroque style, is a dramatic and extravagant design aesthetic. Rococo architecture is most commonly associated with buildings built during the 18th century in France, but the style also impacted the arts, music, furniture design, and even tableware. However, in comparison to other artistic revolutions, Rococo characteristics were only prevalent for a short period of time.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Rococo Architecture – Exploring the Rococo Era and Its Style.” Art in Context. March 4, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/rococo-architecture/

van Huyssteen, J. (2022, 4 March). Rococo Architecture – Exploring the Rococo Era and Its Style. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/rococo-architecture/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Rococo Architecture – Exploring the Rococo Era and Its Style.” Art in Context, March 4, 2022. https://artincontext.org/rococo-architecture/.