Primitive Art – An Exploration of the Origins of Primitivism in Art

Primitivism art, a complicated and frequently paradoxical trend, brought in a new means of viewing and exploiting forms of so-called primitive artwork, and had a significant part in dramatically shifting the course of American and European art at the beginning of the 20th century. Primitivism in art wasn’t really a school as it was a tendency among varied contemporary artists from many nations who were seeking to the past and foreign cultures for fresh aesthetic materials as urbanization and industrialization increased. Starting around the 19th century, the flow of African, Oceanian, and Native American tribal artworks into Europe provided Primitivist painters with a new visual language to develop. Primitive paintings, in many respects, gave artists a platform to criticize the staid conventions of European art.

An Exploration of Primitive Artworks

The employment of simplified forms and more abstracted figures in Primitivism art diverged dramatically from conventional European ways of depiction, and contemporary artists like Picasso, Gauguin, and Matisse revolutionized visual arts using these forms.

While Primitivism in art appeared to be an endeavor to integrate and elevate indigenous traditions, it was an essentially Eurocentric undertaking that, in many instances, was prejudiced against the very traditions it stole.

Throughout the late 20th and early 21st centuries, artists and researchers worked to properly contextualize Primitivist artworks and highlight their flaws as a model for comprehending art from non-European civilizations.

Primitivism Definition and Ideals

Primitive artwork, as perceived by modern painters, not only gave new visual forms, but also a richer and more comprehensive spiritual and emotional template that the artists used to criticize the industrialization of Western civilization.

Primitive paintings, laden with nostalgia, sought links to a pre-industrialized period in which individuals were more linked with the environment and one other.

The long-lasting legacy of Primitive paintings, as well as long-held ideas about the poor quality of work from colonial places, have made it difficult to include artists from Africa, Aborigines, and Native America in art historical narratives, but efforts to create a universal art history are ongoing.

Current reactions to Primitivism in art, frequently by African American painters and those with a link to diverse African countries, are an endeavor to examine, recover, and rethink the entirety of African history in contemporary culture, rather than just imitate the styles of tribal arts.

The Origins of Primitivism Art

The word “primitive” comes from Latin and means “first or oldest of its sort.” Explorers of the South Pacific and Africa returned with stories of new cultures that bore little resemblance to what Europeans understood or cherished.

Europeans appreciated these new civilizations for their exoticism, but they also looked down on them, considering their demeanor and practices to be basically “uncivilized.”

According to art historians, the term “primitive” does not arise without the concept of the “civilized.” The two concepts are inherently linked and produce an ideological framework that portrays what is primitive deficient in complexity.

Nevertheless, fascination with the primitivist artform also alluded to a nostalgic predisposition to highlight a pre-industrial era in which one’s relationship to nature was important.

The Emergence of the Noble Savage

The fascination with primitivist art was widespread in contemporary European society, defining a new trend in both intellectual and cultural worlds. Philosophers of the 18th century investigated the dualities between the logical and the illogical, the organic and the artificial, pushing people to rethink their own roles in civilization.

With rapid urbanization and the emergence of industrial growth, Enlightenment authors endorsed the concept of the primitive way of life, distancing themselves from cultural and technological advancements that permitted for a more natural rhythm and balance with nature.

This longing for a new simplification in life was further linked with the concept of “arcadia,” portraying the primitive as a kind of lost utopia. The concept of the “noble savage” was popular during this period, which many considered as a fall from earlier periods; civilization had become corrupted, governed by persons characterized by selfishness, egoism, and a thirst for control.

The primitivist, who is said to be more in touch with nature, was seen to be better in character and kindness to the contemporary, immoral man.

As modernity took hold, individuals, particularly artists, started to rebel against the industrialization and urbanization they witnessed. Artists began to explore other civilizations and traditions in order to counteract what they saw as confining and stagnant Western conventions.

Primitivism in Art Towards the Close of the 19th Century

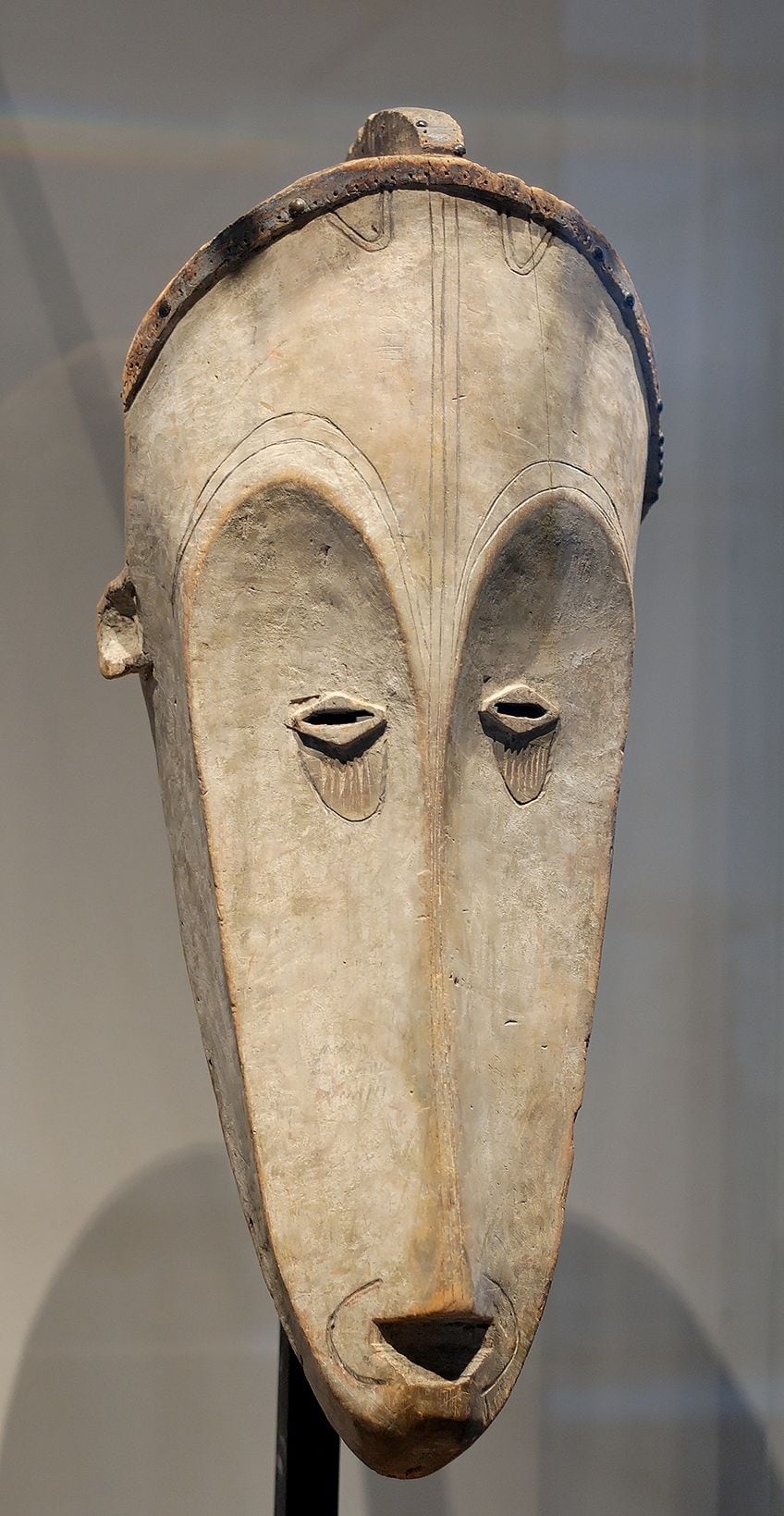

Masks and sculptures from Oceania and Africa, as well as artifacts from Native American cultures, found their way into museums in London, Paris, and Berlin, and were shown in global fairs for the general public to witness. The Trocadéro Museum, Paris’ first ethnological museum, was established in 1878. The museum featured a variety of items from throughout the world that was supposed to be disappearing as a result of colonialism.

These artifacts, now separated from their initial historical backgrounds, were not deemed art in the European context, but for this very reason, many artists seeking characteristics and strengths that contradicted the classical, stringent academic customs decided to turn to these artifacts for motivation and verification of their own aesthetic studies.

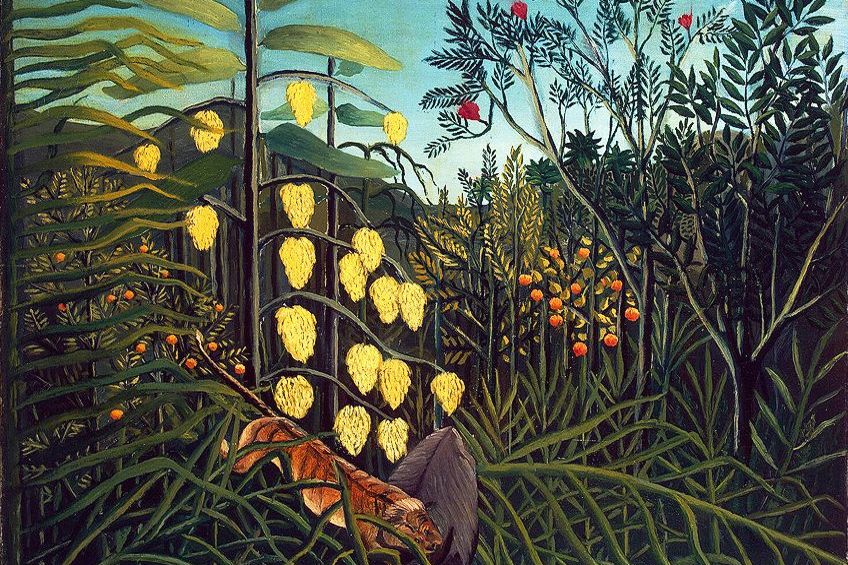

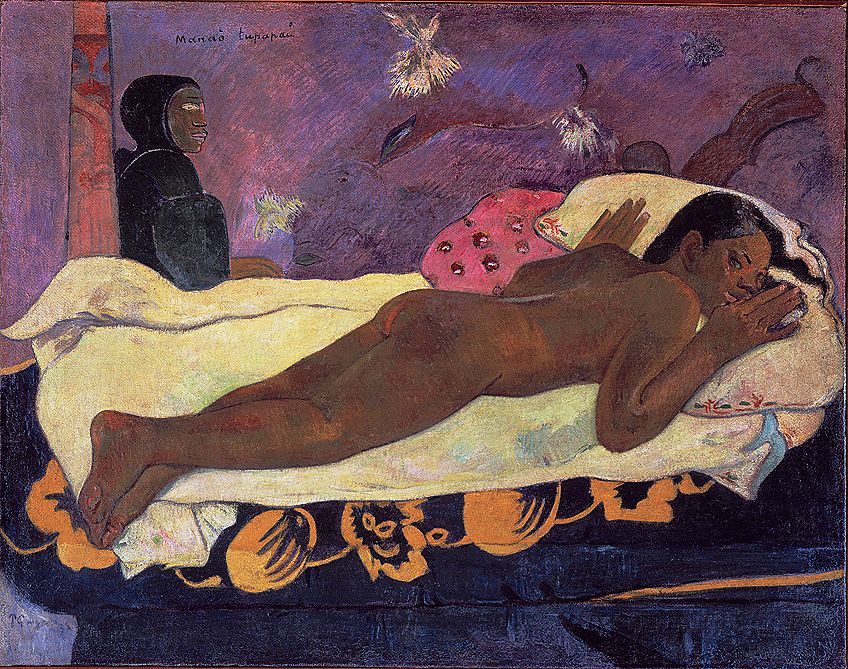

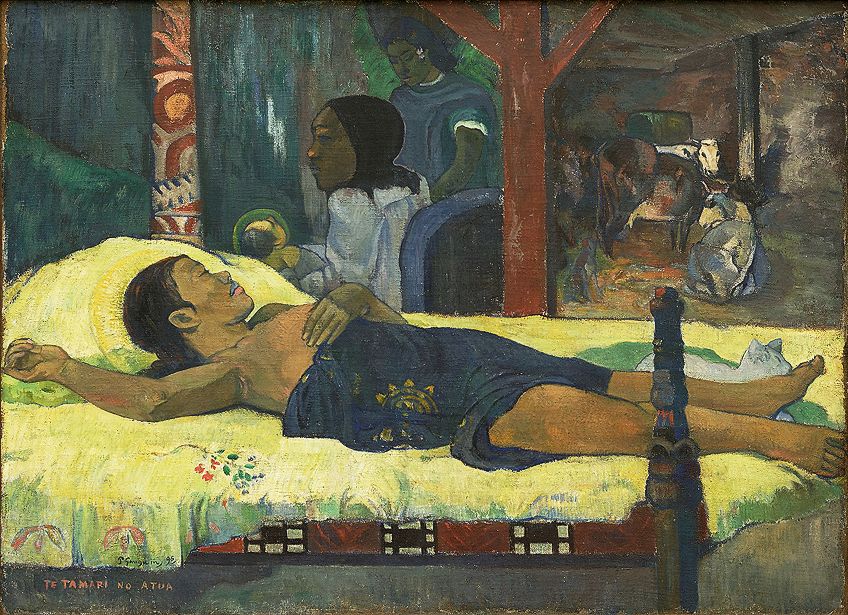

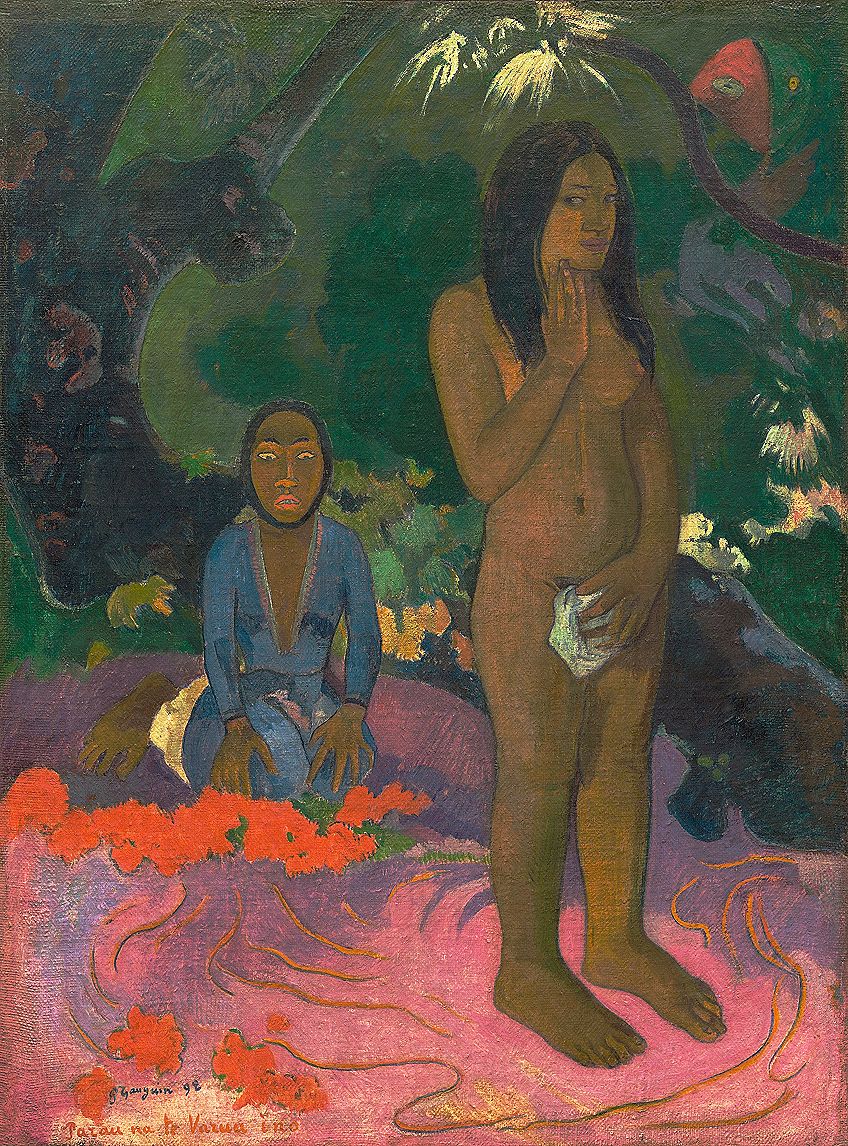

Many attribute this trend toward Primitive paintings to Paul Gauguin, who used flat decorative effects and expressionistic forms comparable to those he saw in museums and on his journeys to Hawaii and Tahiti, as well as the rural region of France that had become widely known with painters in the mid-19th century.

Regional traditions and religious ceremonies harkened back to a simpler period, which artists and other city people yearned for. Gauguin’s curiosity with these other civilizations drove him to push his artistic experiments even farther into unconventional territory.

Dissatisfied with the Impressionists’ observational technique, Gauguin and fellow Symbolists sought to transmit thoughts and feelings via lines and colors, manipulating rustic and foreign subjects.

Primitive Artwork in the Early 20th Century

Different artists, including the Fauves and a variety of German Expressionists, recognized in Primitive objects a more fundamental lexicon of form that was more in accord with portraying the growing contemporary experiences than the national academies’ conventions.

Matisse purchased a tiny African figure, now recognized as a Vili figure from the Congo, in a little store on his way to Gertrude Stein’s residence in 1906, introducing his friend and competitor Picasso to primitive artwork.

Following this initial interaction, Picasso started attending the Trocadéro, becoming particularly enamored by the African Fang masks. His adoption and research of Primitivism’s formal characteristics aspired to transform art as a whole. Picasso’s early Cubist painting Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) is possibly one of the most well-known instances of contemporary art’s borrowing of primordial art forms, despite Picasso’s subsequent dismissal of the influence.

Amadeo Modigliani was principally influenced by the masks of the Baule inhabitants of the Ivory Coast, sketching their heart-shaped outlines and constricted chins, while his workshop colleague Constantin Brancusi noticed parallels between the wooden pieces and his own Romanian sculptures. These basic shapes served as the foundation for his dramatically basic sculptures.

Primitive art was also adopted by the Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter groups in Germany. Franz Marc and Kandinsky first observed African sculptures at Berlin’s Ethnographic Museum in 1907. Kandinsky, rather than being motivated by certain shapes, set out on a journey to include all artistic manifestations.

“For the Blaue Reiter, ‘the primitive’ might just as easily imply children’s paintings as it could tribal craftsmanship,” art historians argue. The painters of Die Brücke embraced Primitivism fully, not merely appropriating creative forms, but constructing an entire lifestyle based on the notions connected with Primitivism. In city workshops, artists re-created the envisioned milieu of tribal life. In the rural areas, farmers’ way of life was valued for its own sake.

During their summer holidays, some painters even ‘ went native,’ living naked with their subjects and enjoying a sexual companionship that mimicked – or so they imagined – the purported innate openness of tribal society. Artists from the United States, like Marius de Zayas, came to Europe and witnessed firsthand the effect of Primitivist art forms on the avant-garde.

Weber started gathering African sculptures and occasionally put items in still works of art, and de Zayas brought back African pieces for photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Stieglitz made a significant contribution to the early spread of Primitivism art in America by displaying works by Brancusi, Matisse, and Picasso alongside African art and Mexican ceramics.

In the 1920s and 1930s, philosophers such as Alain Locke underlined the significance of African American painters drawing inspiration from African art. Rather than utilizing forms without regard for their original settings, Harlem Renaissance painters like Beauford Delaney and Aaron Douglas drew from African history and art and merged their experiments with contemporary avant-garde aspects to establish a new perspective of and for contemporary African Americans.

Surrealist painters later became interested in primitive art, albeit they valued Native American and Oceanic art over African Artwork. The Surrealists were more interested in the unseen energies inherent within early art than they were in its structural advances.

They believed that these primitive societies were more in tune with the spirit realm and provided a model of how to overcome Western materialism and connect it into a universal discourse through the subconscious.

Primitivism Styles and Concepts

With greater travel and Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt in 1798, European painters grew interested in the Eastern civilizations of the Middle East, Asia, and North Africa during the 19th century. There was a rising demand for products from these nations, including fabrics, ceramics, and fashion. Painters like Ingres and Delacroix showed exotic, and sometimes eroticized, images of harem ladies and ordinary life.

Using brilliant colors, the painters created genuine settings that were either fictitious or a mash-up of numerous aspects, perpetuating Western prejudices of the East.

Orientalism and Primitivism

Orientalism, which is founded in imperialist views, frequently portrays the non-Europeans as unenlightened or illogical, justifying European intervention in that culture. Primitivism parallels these early fixations with Eastern civilizations.

Both are based on a notion of European supremacy and are built via complicated, and sometimes conflicting, appropriation and depiction tactics.

While Orientalism is obsessed with established countries, Primitivism is obsessed with the early phases of cultural evolution. In this respect, primitivism entails a return to an allegedly more ideal condition of coexistence with nature.

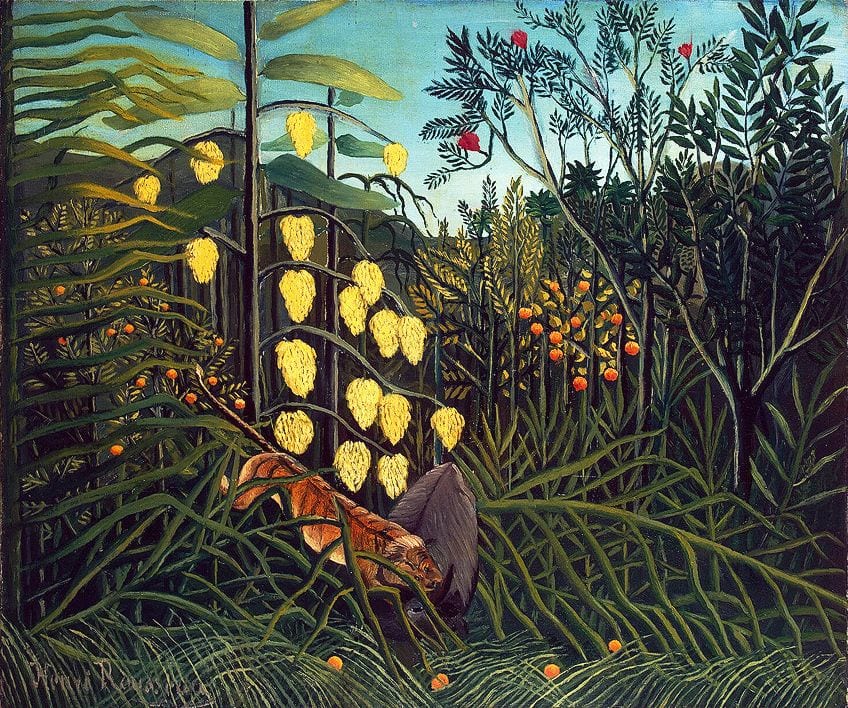

Naïve Art and Child Art

Primitivism’s popularity coincided with the popularity of child art in many respects. Children’s art does not adhere to pre-established standards or customary conventions since they lack professional instruction.

At the start of the 20th century, artists and commentators compared children’s drawings to primitive peoples’ art because of their purity and instinct.

In 1885, Viennese artist Franz Cizek stated that children made art with intrinsic artistic worth, and he advocated for free expression and the use of imagination in educating children. Children’s drawings were representative of a creative process that was not unduly intellectualized and appeared more straightforward for painters such as Picasso, Matisse, Chagall, Kandinsky, and Klee, who were investigating abstract shapes without any narrative function.

Children’s artwork, in addition to reconsidering the creative side, attracted artists in their manner of experiencing the world. Marc Chagall’s fanciful shapes and arrangements were inspired by children’s art, and he used familiar and instinctive motifs to create a type of fairytale universe.

Naïve painters were sometimes referred to as “contemporary primitives,” highlighting the philosophical foundation of how people perceived their work.

Neoprimitivism

The New York Museum of Modern Art held a large exhibition highlighting Primitivism in 1984. The exhibition featured works by famous European and American painters, ranging from Gauguin through the Abstract Expressionists and more current artists.

The paintings and carvings were shown alongside African, Oceanic, and indigenous works with comparable formal features. While the organizers meant for the exhibit to be a clear examination of which contemporary artists saw which African and indigenous items, it instead sparked a flurry of significant criticisms.

The curators, according to the show’s detractors, exploited the anonymously sourced and fragmented arts of primitive civilizations as easy material for modern artists rather than pieces of art in their own sense. The organizers strictly restricted the audience’s encounter of the selected artworks through configuration and incorporating wall texts, according to one of the exhibit’s most vocal opponents, Thomas McEvilley.

This was so that the modern European designers were observed as clever and innovative, rather than mere appropriators of other societies’ craftsmanship.

Famous Primitive Paintings

Now that we have explored the Primitivism definition and concepts, perhaps we should take a look at some examples of Primitive paintings. These artworks will help give us a better understanding of the use of Primitivism in art. Here are some of our favorite examples of Primitive artwork.

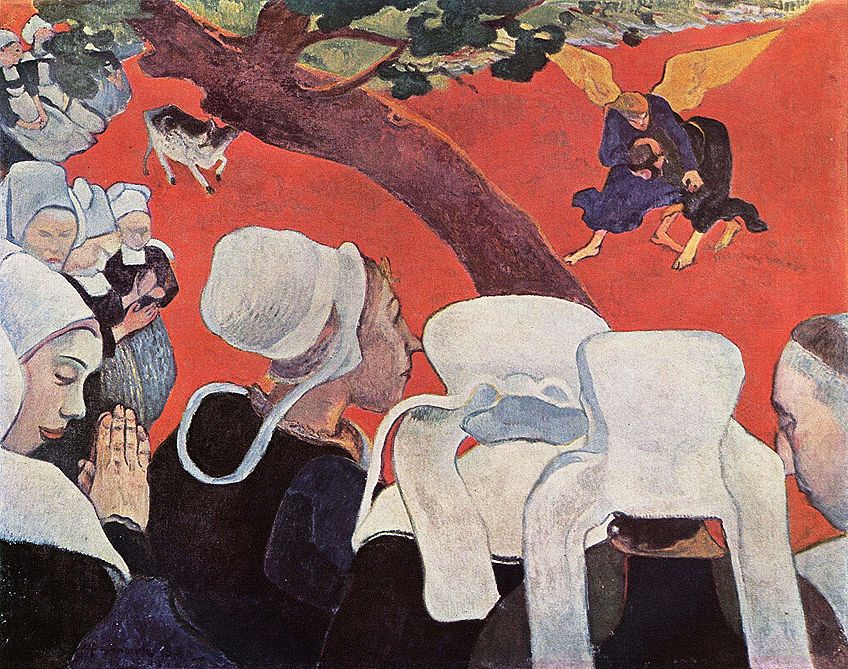

Vision After the Sermon (1888) by Paul Gauguin

| Date Completed | 1888 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 72 cm x 91 cm |

| Current Location | Scottish National Gallery |

Gauguin depicts a visionary scenario in which ladies in white bonnets and black robes stand with their backs to the observer, several with their eyes closed and hands joined in prayer, seeing a scenario from the Old Testament, Jacob battling with an angel. Gauguin paints the heavenly vision on a crimson background to indicate that it is not taking place in the physical world.

Gauguin and other Symbolists were establishing a new visual language at the time, which is reflected in the compressed space and simplified shapes. Gauguin equated his composition’s simple and flattened outlines with the Breton people’s “primitiveness,” as he saw it.

Such abstractions have links with both Breton religious activities and Symbolist aesthetic appeal in that they relate to an inner significance rather than outward reality. Gauguin notably depicted Polynesian girls and women in eroticized stances in abstracted vistas and interiors, using these newly discovered shapes and abstractions to portray comparable parts of Tahitian society that he subsequently met.

Before Gauguin’s renowned South Pacific voyages and move to Tahiti to escape the oppressive conventions of civilized, contemporary Paris, he and others sought refuge in Brittany, a rural region of Northwest France known among painters for the regional practices and traditions connected with peasant life.

Gauguin’s primitivism inclinations were fully established in the late 1880s paintings he made in Pont-Aven, according to art historian Gill Perry. Gauguin described his visit to Brittany in a letter to a fellow artist, “Brittany is one of my favorite places in the world. Something primal and primeval appeals to me here. I hear the low, muted forceful sound that I’m looking for in my picture as my clogs reverberate on this rocky dirt.”

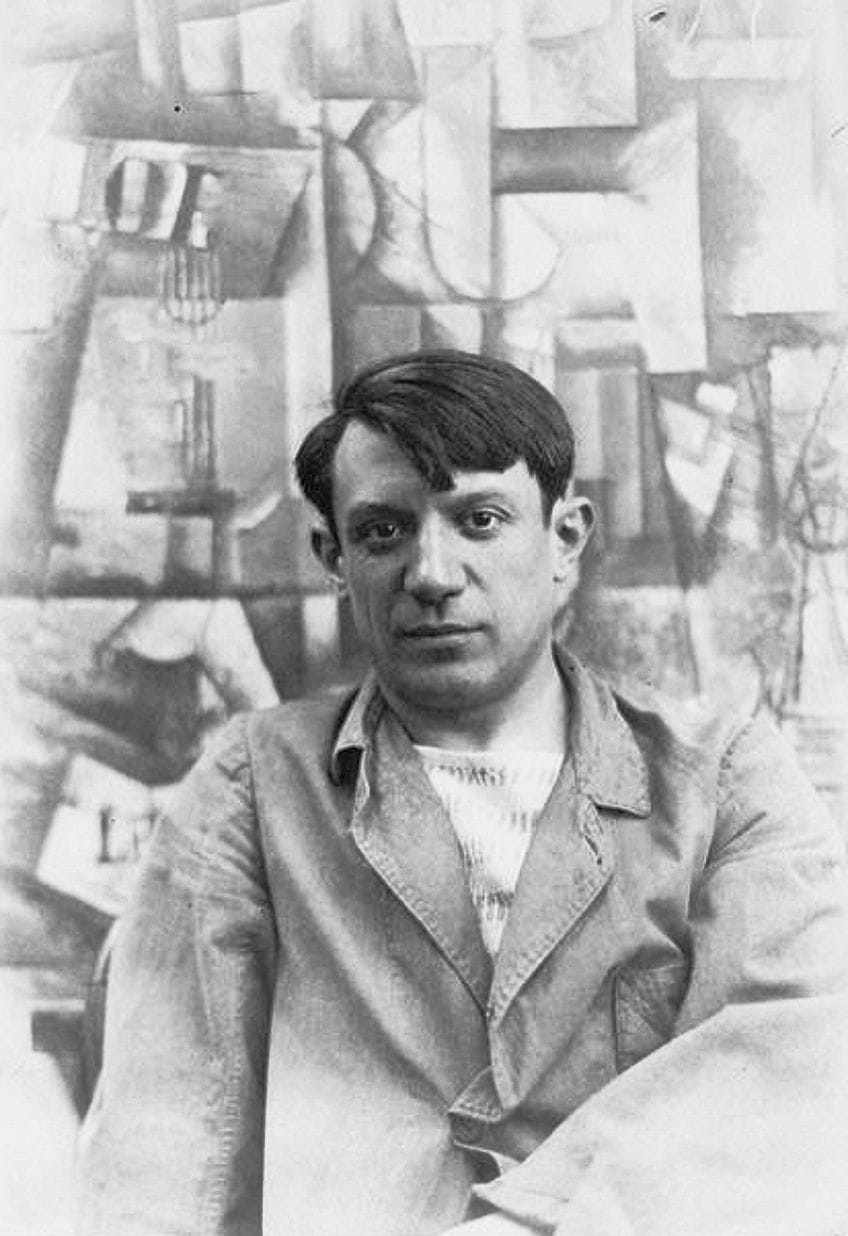

Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907) by Pablo Picasso

| Date Completed | 1907 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 244 cm x 233 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

This primitivist artwork features five naked girls in various attitudes and is one of the most famous paintings of the 20th century. Most of the women have their backs to the spectator. Three of them have mask-like faces, and their limbs are geometric and abstract. While the scene is stylized, with hints of a drape and a still life on a small table in the front, the ladies are clearly in a brothel according to Picasso’s extensive studies.

Picasso mixes his study of Primitive art, notably African and Iberian sculpture, with allusions to Michelangelo to construct a new synthesis that would have repercussions throughout the 20th century in this pioneering pre-Cubist work.

Picasso’s imitation of primitive art has gotten a lot of attention. He was already interested in early Iberian art and Romanesque art, and following a talk with Henri Matisse and trips to the Trocadéro Museum in 1906, he started to collect African sculptures for himself.

Picasso remembered in 1937 a revelation he had in 1907 when visiting the Trocadéro. While the museum’s scents and layout turned him off, Picasso recalled that when he saw the African artworks and masks, he recognized, “The masks were unlike any other sculpture. Not in the least. They were pathfinders – the Negroes’ sculptures – against everything; mysterious, menacing spirits.”

Picasso took on the technical aspects of African masks, including oval curved faces and geometric and angular face shape, but he also took on the notion that the method of producing a piece of art may be seen as an inherent component of its purpose.

While Picasso was unaware of the meanings and purposes of these masks, when he defined “Les Demoiselles” as his “first canvas of exorcism,” he related the ceremonial and mystical characteristics he thought they had to his own creative processes.

Bathers in a Room (1909) by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner

| Date Completed | 1909 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 151 cm x 199 cm |

| Current Location | Tate Museum |

Kirchner transposes the customary bucolic, outdoor scene of customary bathers into his workshop, vividly colored and furnished with pseudo-Primitive objects and fabrics, in this large-scale painting. In the middle area, tall, dark sculptures adorn the entrance jamb, while a brightly colored curtain divides two chambers on the left. A sitting monarch and an amorous pair may be seen in the roundels on the curtain.

Kirchner had seen African and Oceanic sculptures at the Dresden Anthropological-Ethnographical Museum and was familiar with them.

As art historians point out, the Primitive artifacts, together with the vivid colors, deformities, and contours of the figures, would have suggested a “direct” or “genuine” representation then identified with Primitive, or uncivilized, societies.

In the 1906 manifesto Die Brücke, it is said, “We gather all young with trust in development and a new generation of producers and watchers. As youth, we bear the potential in us and desire to create freedom of existence and movement for ourselves in opposition to long-established elder forces. We embrace as our own everyone who directly and authentically reproduces what inspires him to create.”

The embracing of the Primitive by Die Brücke signaled their hostility to bourgeois ideals and the quickly industrializing environment, as well as their mediator between so-called Primitive thinking and contemporary thought and fantasies.

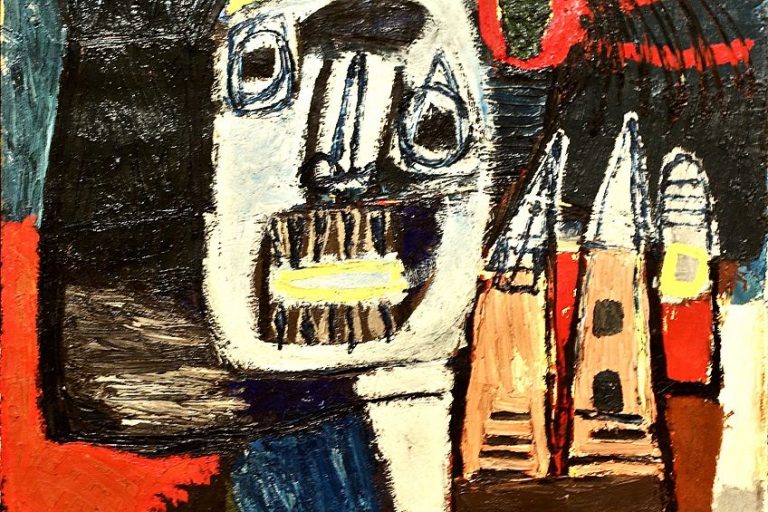

Childbirth (1944) by Jean Dubuffet

| Date Completed | 1944 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 100 cm x 80 cm |

| Current Location | Museum of Modern Art |

A lady gives birth to a baby while two bystanders stand by her side in this stunning shot. Dubuffet’s rendering of the feminine form is coarse and simple. Her limbs and hands are lifted, and her legs are spread out, while the baby appears between her legs. Dubuffet has angled the bed on which she is lying toward the picture’s surface, flattening the entire arrangement. Dubuffet created art that appeared incompetent and childish.

He looked to examples of Primitive art, as well as work created by children and the mentally sick, to discover an artistic expression that questioned standard Western norms. Dubuffet pioneered the concept of Art Brut, often known as raw art or “outsider art”; it refers to art, including his own, created outside of academic traditions and by persons who did not regard themselves as artists.

Dubuffet told his audience in a 1951 speech that he believed the art of so-called primitive persons was more advanced than Western art, adding “Personally, I strongly believe in barbaric characteristics such as instinct, emotion, emotion, violence, and lunacy. For myself, I strive for work that has an immediate link to daily life, art that is a very direct and true depiction of our real lives and feelings.” However, like many other European painters who have shown an interest in primitive art before him, Dubuffet fails to recognize the indigenous customs and education that were the setting of the work he commended.

Primitivism art, a multifaceted and usually contradictory trend, introduced a new way of interpreting and utilizing forms of so-called primitive artwork and had a vital role in significantly modifying the direction of American and European art around the turn of the twentieth century. Primitivism in art was not so much a school as it was a trend among several current artists from various countries who were looking to the past and other cultures for new aesthetic resources as urbanization and industrialization expanded. Beginning in the late 19th century, the influx of African, Oceanian, and Native American tribal artworks into Europe presented Primitivist painters with a new visual vocabulary to work with. In many ways, primitive paintings provided artists with a platform to challenge the staid traditions of European art.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are Primitivism Art and Neoprimitivism Art?

Primitive art, as regarded by contemporary painters, provided not only new aesthetic forms but also a deeper and more thorough spiritual and emotional template that artists utilized to attack Western civilization’s industrialization. Primitive paintings, drenched in nostalgia, sought linkages to a pre-industrialized era when people were more connected to the environment and one another. The long-lasting impact of Primitive paintings, as well as long-held beliefs about the low quality of work from colonial regions, have made it difficult to incorporate artists from Africa, America, and the Caribbean in art historical narratives, but efforts to construct a universal art history are underway.

How Did the Idea of the Noble Primitive Arise?

During this time, which many saw as a decline from earlier periods, the image of the “noble barbarian” was prevalent; civilization had been corrupted, dominated by people marked by greed, egoism, and a craving for power. The primitivist, who is thought to be more in touch with nature, was considered as having a better character and being more sympathetic to the modern, immoral man. Individuals, particularly artists, began to protest against the industrialization and urbanization they experienced as modernity gained hold. Artists began to investigate other cultures and traditions to combat what they perceived as restrictive and static Western standards.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Primitive Art – An Exploration of the Origins of Primitivism in Art.” Art in Context. March 11, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/primitive-art/

Meyer, I. (2022, 11 March). Primitive Art – An Exploration of the Origins of Primitivism in Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/primitive-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Primitive Art – An Exploration of the Origins of Primitivism in Art.” Art in Context, March 11, 2022. https://artincontext.org/primitive-art/.