Medici Family – Who Were the Medicis, the Famous Art Family?

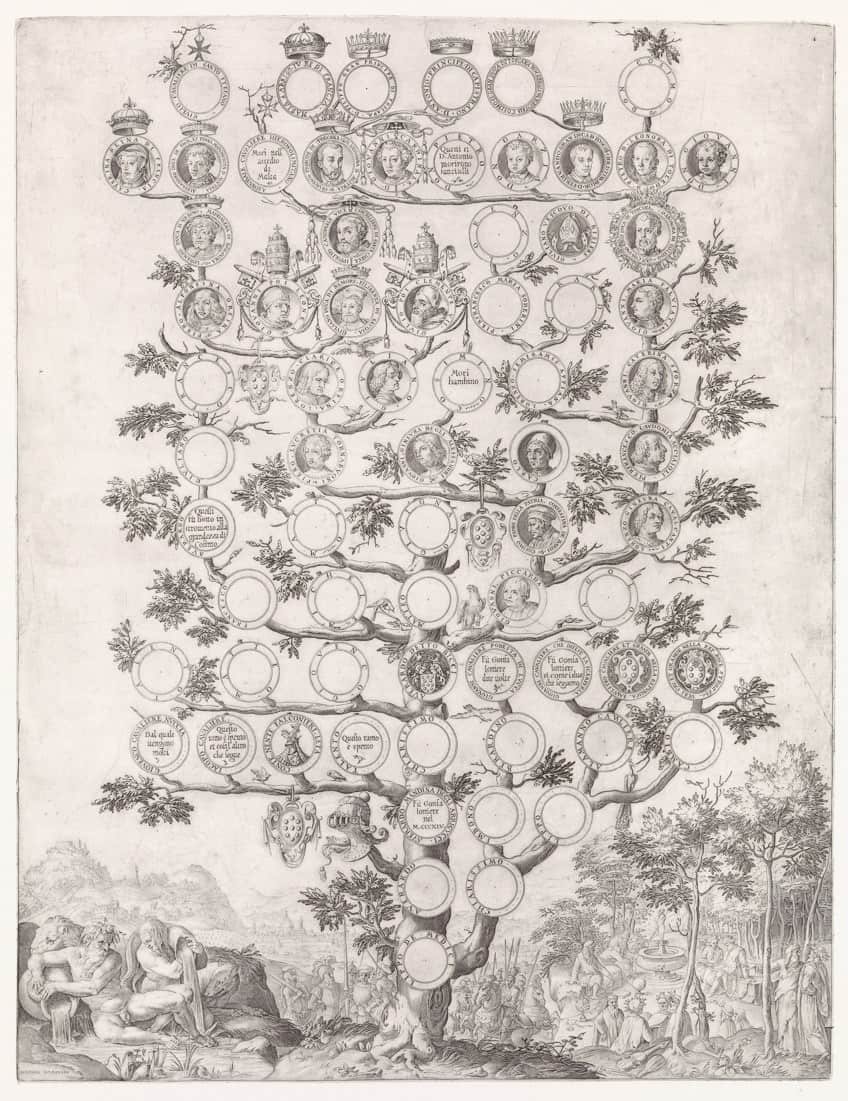

Who were the Medicis and for what is the Medici family famous? The Medici family members are known as the central figures of the Renaissance because they laid the foundation for Florence’s cultural success. Members of the Medici family tree are credited with great advancements in art, banking, and architecture that are still in use today. Today we will be discussing the Medici family history and legacy, exploring how individuals such as Lorenzo de’ Medici helped shape the world of art.

The Medici Family History

The Medici family was an apolitical and financial lineage from Italy that rose to power in Florence in the early 15th century under Cosimo de’ Medici. The family steadily flourished until it was successful in establishing the Medici Bank. The Medicis’ ascent to political authority in Florence was aided by this institution, which was the greatest in the European region during the 15th century, despite the fact that they remained civilians rather than kings until the 16th century. The Medici family members’ wealth and power came from the textile trade, which was overseen by Florence’s wool guild.

The Medicis, like other dynasties reigning in Italy, controlled their city’s governance, were capable of putting Florence under their control, and established an atmosphere conducive to the flourishing of art and enlightenment.

The Rise to Power

Cosimo the Elder established the Medici bank in Florence. He spread it to other city-states, such as Venice, Geneva, and Rome, where the Papal States began collaborating with his company. During his lifetime, he would go on to open branches in locations such as Bruges, London, and Lübeck. These branches made it simple for the Papacy to place orders for products throughout Europe and for bishoprics to submit costs from afar. Their bank’s renown is based in part on its location.

Some of the financial technologies we use today were invented by the Medici bank. They pioneered the technique of keeping track of a payer’s debits and credits in a single log. This made calculating one’s net worth quicker and more precise.

Moreover, transferring significant quantities of money across the region to pay for foreign items was risky at the time. Letters of Credit were invented by the Medici Bank to address this problem. In reality, this may resemble an Englishman repaying a Medici Bank in London in the local currency of pounds for a piece of Florentine art. The Florentine bank would then issue the artists with a Letter of Credit as an assurance of reimbursement. The artist may then deliver the piece and get his bank’s payment in his own country’s currency.

These accomplishments helped the Medici family tree become Europe’s richest.

Medici Family History of Art Patronage

Florence was not regarded as the most militarily strong nation among others such as Naples, Milan, and Rome. This left it susceptible to conquest during a time when Italian city-states battled for dominance. The Medici family members, on the other hand, were outstanding diplomats. Cosimo the Elder thought that conflict harmed trade and worked to bring a succession of battles in Lombardy to a stop. This assisted the two nations’ creation of a mutual territory agreement.

Lorenzo de’ Medici, his successor, was a staunch supporter of the peace treaty signed by Milan, Naples, and Florence.

Lorenzo also won the admiration of Florentine residents by liberating and clothed galley slaves. In actuality, the painting Pallas and the Centaur (c. 1482) is believed to have been created for him by Sandro Botticelli.

Pallas Athena is the Divinity of Wisdom and Knowledge, while the creature is the symbol of humanity’s ferocity.

Even though Naples possessed a big force capable of defeating the Florentine military, Lorenzo de’ Medici understood how to deal with them. Despite this, Lorenzo preserved Florence independent and safe, earning him the title of Athena and Naples the title of Centaur.

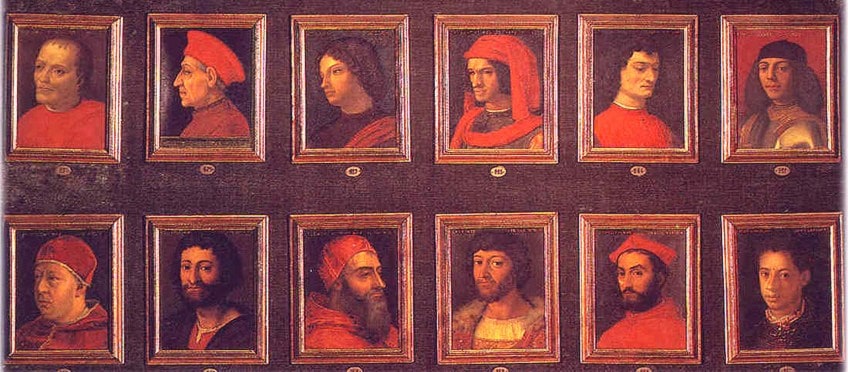

He was a prominent political figure as well as one of the most important Medici benefactors. Michelangelo and Botticelli were among the painters he supported.

Lorenzo de’ Medici and Michelangelo

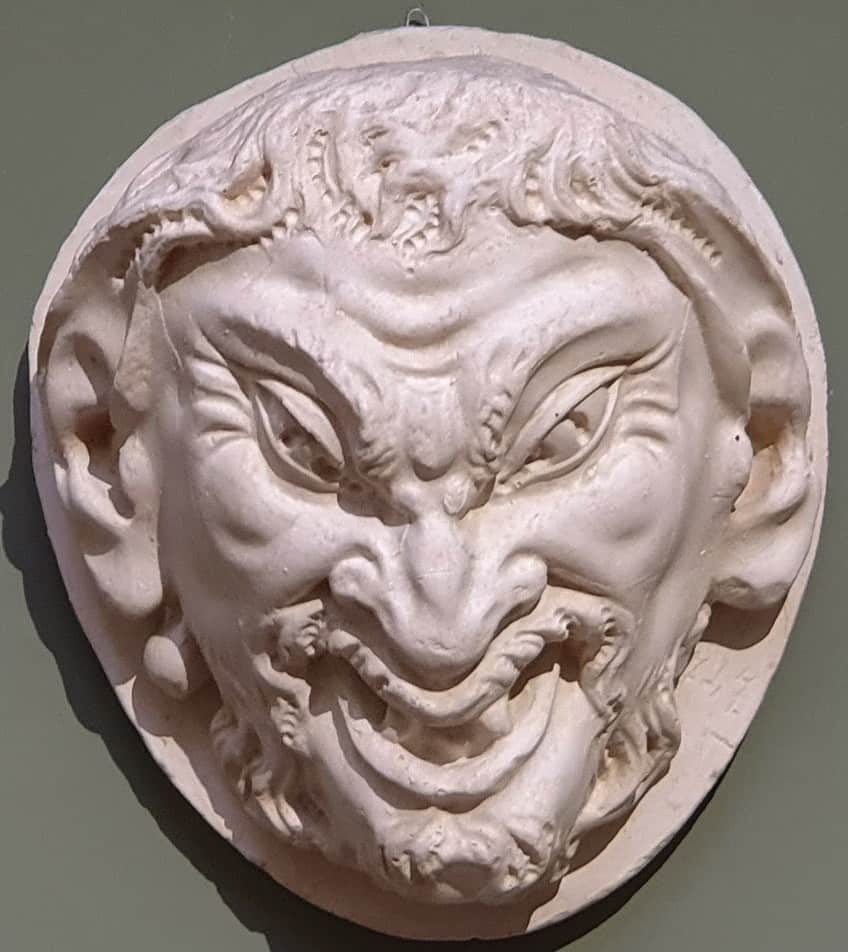

Lorenzo first encountered Michelangelo while he was a young adolescent attending the San Marco Academy. He was carving an old faun stone head when Lorenzo came across him. He lauded the young artist’s talent while also teasing him by noting a mistake: an elderly deer would not have a whole set of good teeth. So, Michelangelo removed a few teeth and re-showed the sculpture to Lorenzo.

Lorenzo was so taken with the young creator’s combination of rapid skill and genius that he asked him to reside in his court from 1490 to 1492.

Michelangelo trained under Donatello, a prominent Renaissance painter. He lived with Lorenzo’s children, the future Popes Leo X and Clement VII, who would later order his art for their Papal States. Michelangelo’s bond with the family survived Lorenzo de’ Medici’s death in 1492.

Pope Julius ordered him to decorate the Sistine Chapel’s upper walls in 1508.

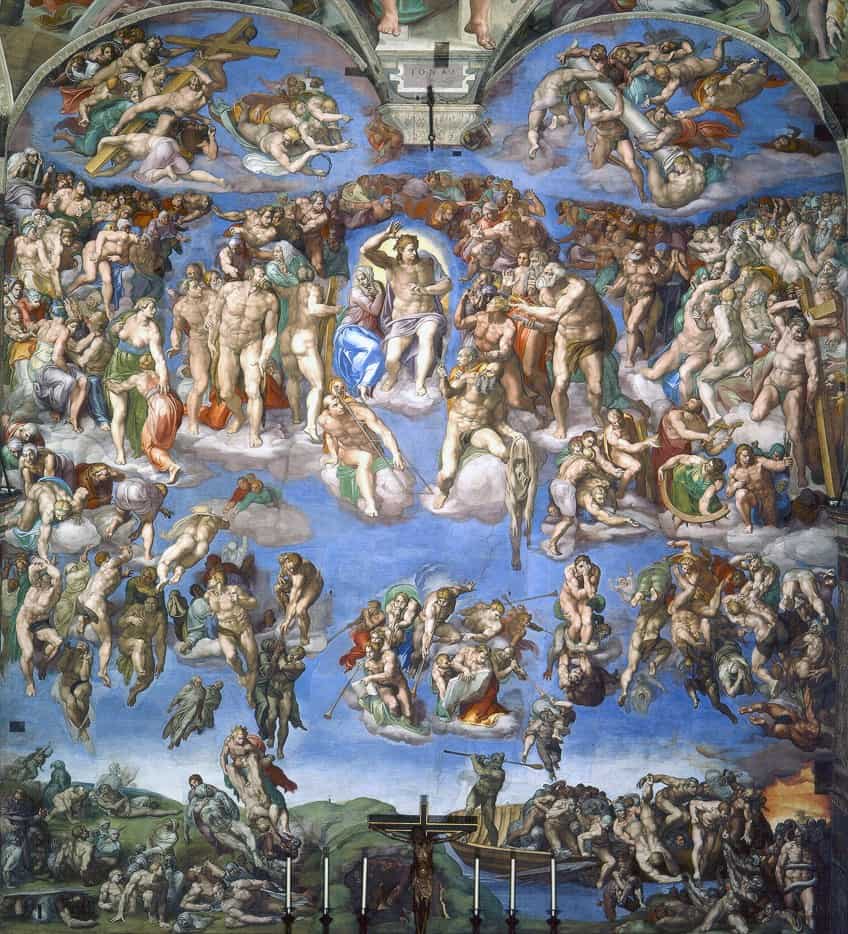

Michelangelo would not work on it again for another 25 years. However, when Pope Clement VII took control, he asked Michelangelo to create The Last Judgment (1536-1541), which drew him back to the altar.

The Medici Family Members and Donatello

The bronze David, Donatello’s most renowned work, was commissioned by Cosimo the Elder. He planned to display it in the Palazzo Medici’s courtyard in Florence. This was a significant item since it was the Renaissance’s earliest standalone bronze cast sculpture.

It was also the area’s first naked man statue since those from Ancient Greece.

Donatello also sculpted Judith and Holofernes (c. 1455) for the Palazzo Medici-garden Riccardi’s fountain. In 1457, it was displayed with a David sculpture in front of Cosimo the Elder’s family residence. The Bible narrative of both artworks is indicative of underdogs defeating oppression. Similarly, the city of Florence saw itself as tyrant slayers, standing strong against its surrounding city-states.

Donatello’s art brilliantly represented the Medici family members’ and Florence’s essential ideals.

Leonardo da Vinci and the Medici Family

Although Leonardo da Vinci’s backing by the Medici family was not as great as that of other painters, he did get his early schooling through their network. Andrea del Verrocchio took him on as an apprentice when he was a teenager. From the 1460s through the 1470s, Verrocchio worked as a carver and artist, creating tombs for Cosimo, and Piero de’ Medici. Da Vinci learned sculpting, painting, engineering, and metals from him. He stayed at Verrocchio for ten years. Notwithstanding this, he was not included on Lorenzo de’ Medici’s list of outstanding artists for the Pope to recruit in 1481.

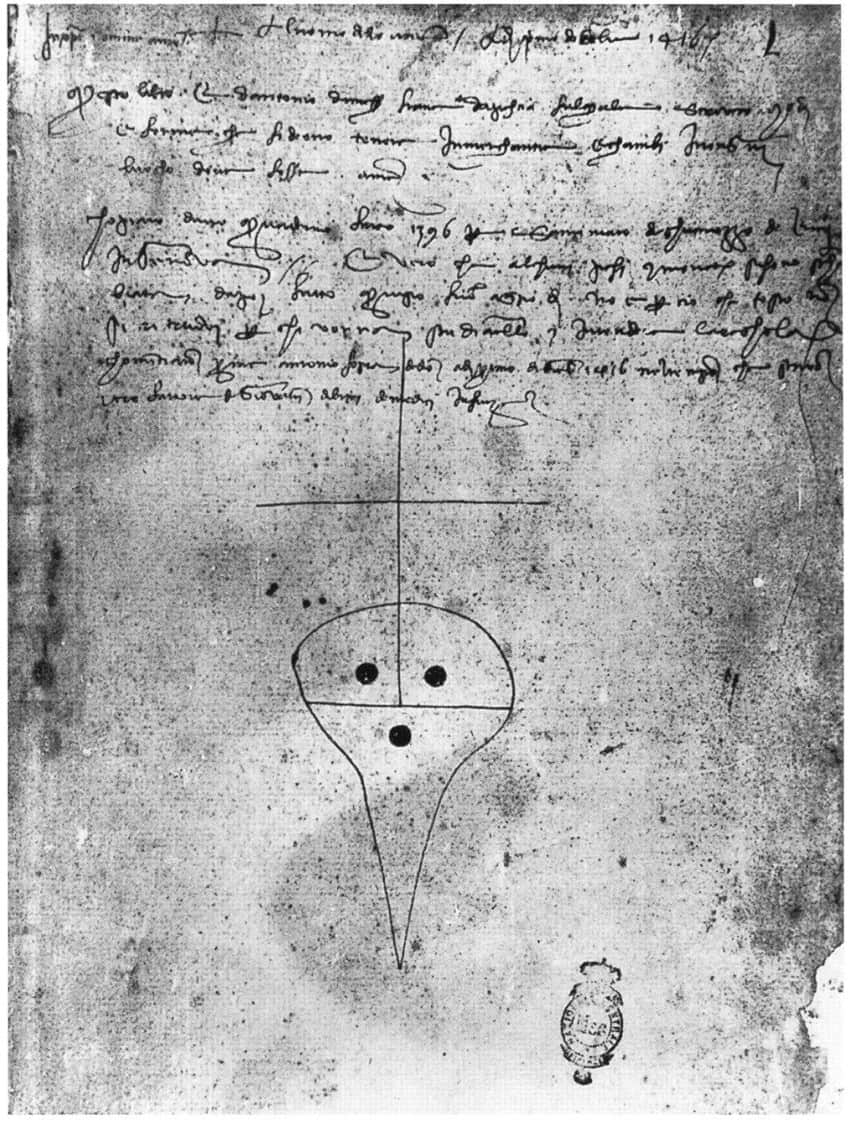

“The Medici produced me and then ruined me”, da Vinci said in a diary entry dated 1515.

Raphael and the Medici Family Members

Raphael’s biggest client was Pope Leo X. He commissioned him to create a series of 10 tapestries for the Sistine Chapel’s lower walls. They depicted the Acts of the Apostles and are presently on display at the Vatican’s Pinacoteca. Prior to Leo X, Pope Julius II commissioned him to produce The School of Athens (1511) and the Disputation of the Holy Sacrament (1509), two of his most famous murals.

However, Leo X continued to pay for Julius II’s construction of the Papal chambers after his demise. Raphael produced The Meeting of Leo the Great and Attila (1514), modeled on Pope Leo I’s visit with Attila the Hun in 452 AD.

Subsequently, he modified Pope Leo I’s visage to look like Leo X.

The Medici Family and Architecture

St. Peter’s Basilica, the Uffizi Gallery, and the Florence Cathedral were all built with the support of the Medici dynasty. The Uffizi was founded by Cosimo I de’ Medici, the First Duke of Tuscany, as an administrative facility for his family.

The term “Uffizi” originally referred to a collection of offices.

In 1765, soon after the last descendant of the Medici family died, it was officially opened as an art gallery. It now holds Baccio Bandinelli’s Laocoön and his Sons (1506) and Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1485-1486).

The construction of St. Peter’s Basilica was also commissioned by Pope Leo X. Martin Luther, the Protestant Reformation’s leader, assailed the Papacy’s greed by accusing him of sponsoring this work. “Why doesn’t the Pope construct the basilica of St. Peter’s from his personal finances?”, he questioned in his 95 Thesis, the paper that kicked off the Reformation.

The Duomo at the Florence Cathedral was commissioned by Cosimo the Elder. Since the cathedral’s development started in 1296, there have been several interruptions, and there is still no dome. It was a technical difficulty for the architects to design it without Gothic buttresses. Filippo Brunelleschi won a contest to find who could design it best. Brunelleschi felt he could construct the dome without the use of scaffolding, but many skeptics remained.

The Medici family, on the other hand, had enough faith in him to support this project. Brunelleschi’s dome reaches 375.7 feet tall today, earning it the title of one of the world’s highest domes.

Plots to Overthrow the Medici Family and Other Conspiracies

The Pazzi Conspiracy was a plan to topple the Medici dynasty by the Papacy and Francesco de Pazzi. The Cathedral of Florence hosted a public mass with a 10,000-person attendance on the 26th of April, 1478. Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano were among those there. The liturgy was interrupted by a bunch of men wielding knives who attacked the two. Giuliano de’ Medici was fatally stabbed, while Lorenzo de’ Medici escaped with just scratches to the church sacristy.

Florentine locals took the matter into their own hands after seeing their adored Lorenzo being assaulted. They kidnapped Jacopo de’ Pazzi, flung him from a balcony, and hauled him to the Arno River. The Archbishop of Pisa, Salviati, was hung outside the Palazzo Vecchio. The strategy backfired, and the Medici dynasty expelled the surviving Pazzi family members from Florence.

Tancredi Scarpelli and Stefano Ussi created paintings to remember the tragedy, which further solidified their dominance over their city.

David and the Rebellion

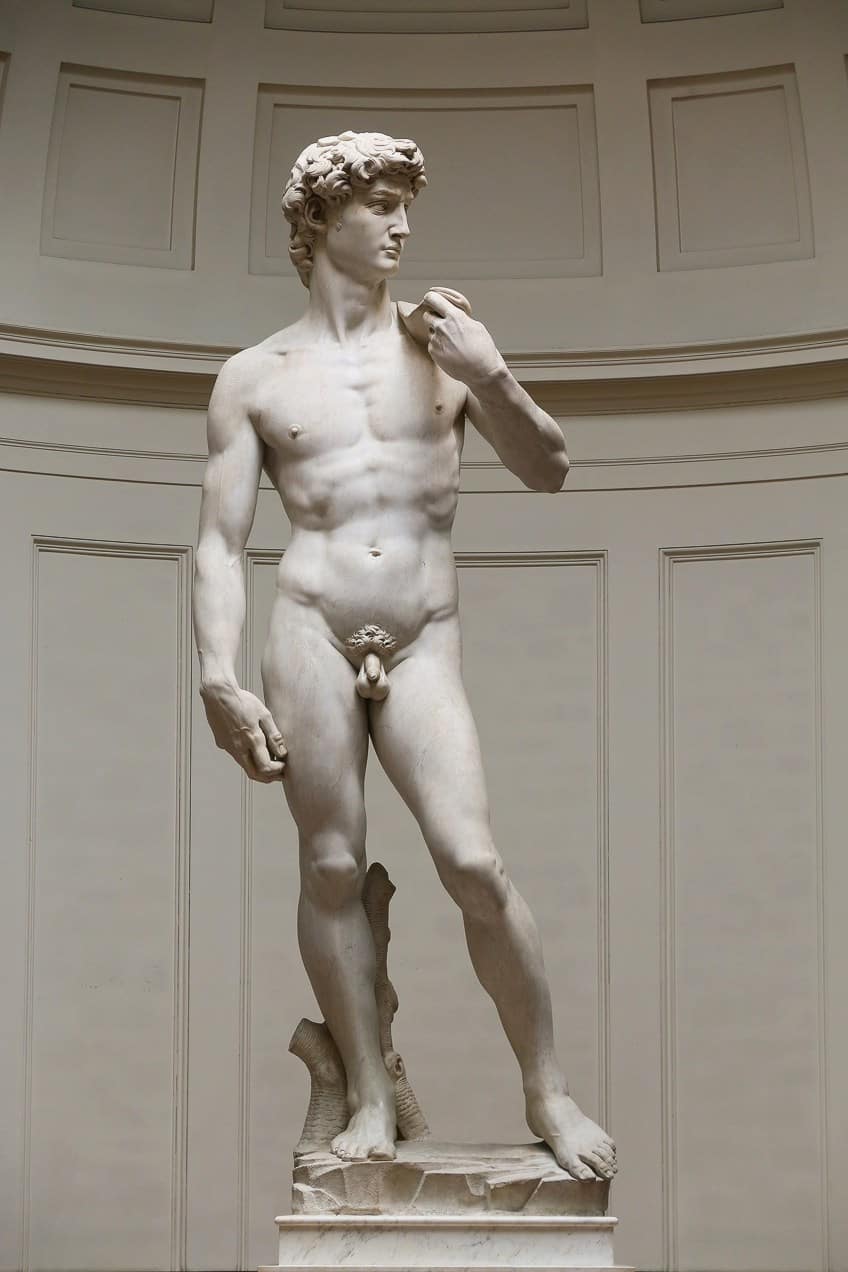

In 1501, the Arte Della Llane ordered the sculpture of Michelangelo’s David (1501-1504) to be installed in the Cathedral of Florence. Due to political defeats, the Medici family had been exiled since 1494 and would return in 1512. The new administration, which succeeded the Medicis, was staunchly anti-Medici. David, the legendary figure who conquered a giant with little more than a rock, was the ideal emblem for a shaky Florence.

Florence was surrounded not just by city-states that were always a danger to its sovereignty, but also by the Medicis, whom some considered as dictators.

Instead, in 1504, the authorities chose to put David in the city hall. They directed David‘s gaze to Rome, where the Medicis were exiled. It’s doubtful that Michelangelo meant it to be political, given that it was initially designed for a Cathedral. This is particularly true given the Medici’s assistance in his own creative growth. Even when a work of the High Renaissance was directed against the Medicis, it was still about them in the end. David is one of the finest Renaissance features today due to his exquisite Renaissance contrapposto and connection.

Machiavelli and the Medici Family

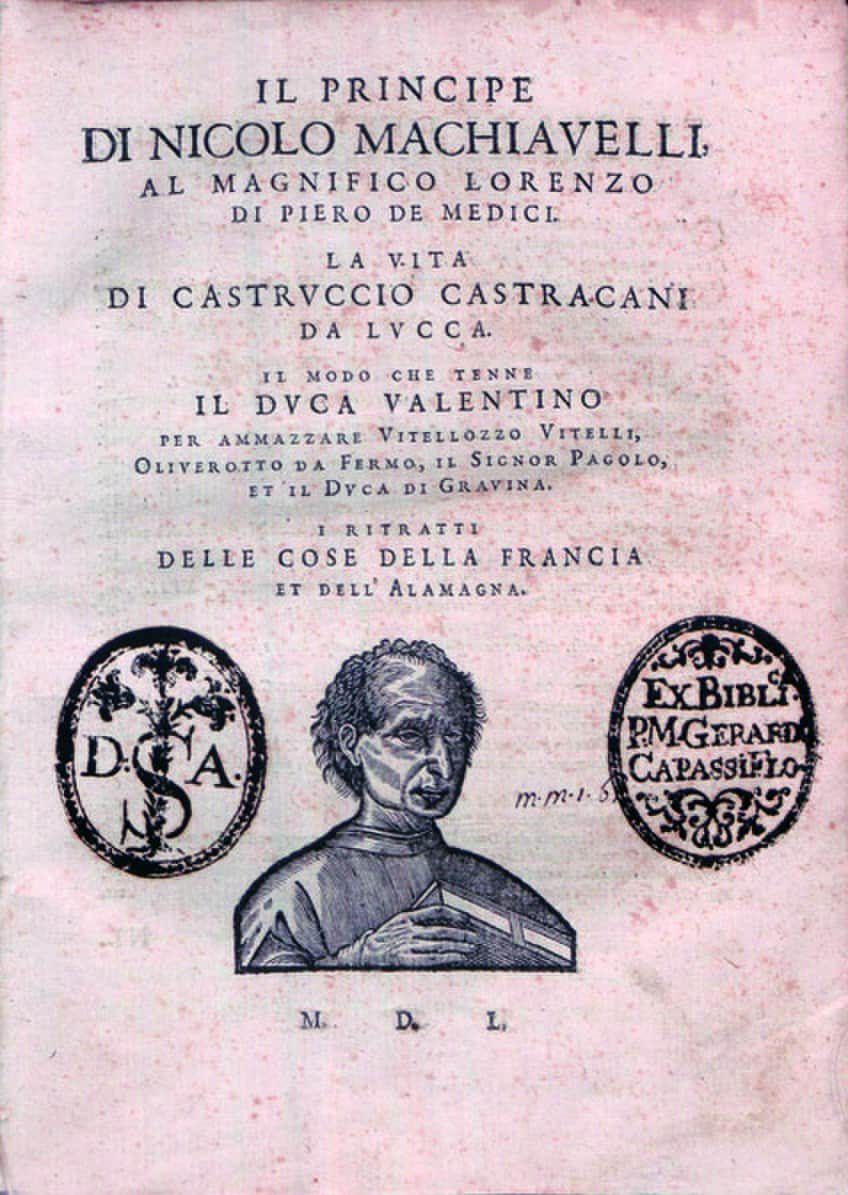

From 1494 until 1513, when Piero de’ Medici relinquished authority to France, the Medici dynasty was exiled. Machiavelli, meantime, was a well-known political thinker and diplomat. He developed a network with Anti-Medici political leaders in the wake of the Medici’s demise.

In 1513, the Medici family reclaimed control and compiled a list of suspects who would most likely plot to depose them. They arrested, tortured, and banished Machiavelli because his name was on the list.

They didn’t have enough proof of his actual participation to put him to death, so Pope Leo X let them stay in exile. The Prince (16th century) by Machiavelli was dedicated to the future Medici leader of Florence as a handbook on how to seize and maintain control of a state. He attempted to use this to get a place within the Medici court, but he was unsuccessful. Only in 1520, when Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici ordered him to create a narrative of Florence, did he re-enter public life.

The Medici Family and Music, Science, and Fashion

Cosimo I de’ Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany, had Galileo Galilei as his tutor. He published The Starry Messenger in 1610, in which he described recent telescopic findings. In it, he mentions Jupiter’s moons, which he refers to as “Medicean stars.” While serving at Fernando de’ Medici’s court, Bartolomeo Cristofori would be the one to develop the piano.

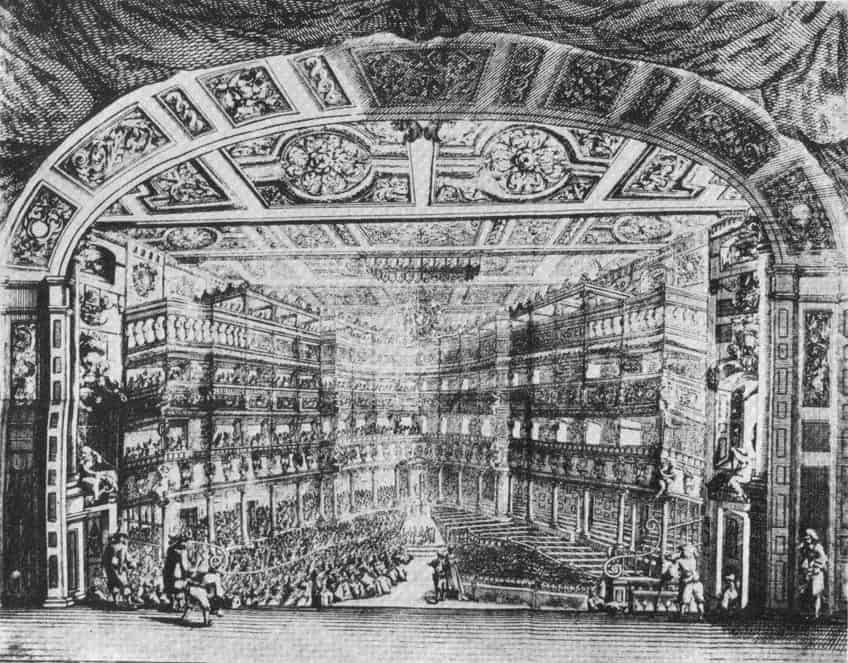

In the late 1500s, operas were born during the Renaissance. The Medicis supported important opera houses such as the Teatro della Pergola (or Pergola Theater) with funds.

King Henry II married Catherine de’ Medici. She was a small woman who sought to make herself look taller before meeting with the French court. As a result, she ordered a pair of high-heeled shoes, transforming them into status symbols. This was extraordinary at a period when butchers avoided getting blood on their feet by wearing high heels.

She was instrumental in improving and popularizing the horse side saddle, allowing ladies to ride without being exposed.

The Last Medici Family Member

The very last Grand Duke of Tuscany, Gian Gastone de’ Medici, passed away without a son in 1737. Anna Maria Luisa de’ Medici was the only surviving family member and had no offspring. She realized that with no one to carry on their bloodline, the authority of Tuscany would fall to Francis of Lorraine. Anna Maria agreed that her family’s paintings, literature, maps, and homes would be passed to them. She did, however, make a Family Pact, pledging that these valuables would not be allowed to leave Florence.

She went on to say, “That none of it shall be misappropriated or taken away from the capital or the Grand Duchy’s territory, because these items are for the adornment of the state, for the welfare of the people, and to entice strangers’ interest.”

Her wishes were carried out by the future leaders. Anna Maria was mostly successful in preserving Florence as the center of the Medici empire. Every year, roughly 16 million people visit Florence to witness what this amazing family created.

Legacy of the Medici Family

The Medici’s greatest achievements were in the fields of art and architecture, particularly early and high Renaissance artwork and architectural style. During the Medicis’ reign, the family was responsible for a large number of notable artworks from Florence.

Their help was crucial because most artists don’t start working on their projects until they’ve been paid.

In 1419, Giovanni di Bicci de’ Medici, the family’s first patron of the arts, assisted Masaccio and contracted Filippo Brunelleschi to rebuild the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence. Donatello and Fra Angelico were two of Cosimo the Elder’s renowned creative collaborators.

Michelangelo Buonarroti, the Medici family’s most important protégé in later years, created works for a variety of family members, starting with Lorenzo de’ Medici, who was claimed to be immensely enamored by the young Michelangelo and asked him to examine the family’s antique sculpture inventory. Lorenzo was also Leonardo da Vinci’s benefactor for seven years. Moreover, Lorenzo was a poet and singer in his own right, and his sponsorship of the arts and literature is regarded as a high point in Medici sponsorship.

Following Lorenzo’s death, Girolamo Savonarola, a puritanical Dominican monk, rose to fame, advising Florentines against excess luxury. Many famous works were “voluntarily” burnt at the Bonfire of the Vanities under Savonarola’s zealous guidance. Savonarola as well as a couple of admirers were burnt to death in the Piazza della Signoria the next year, on the same day as his conflagration. The Medici were prolific enthusiasts, and their collections, along with commissions for art and architecture, today constitute the core of the Florentine Uffizi Museum.

The Medici were accountable for some of Florence’s most noteworthy architectural elements, including the Boboli Gardens, Uffizi Gallery, Belvedere, and Medici Chapel.

Later, the Medici popes in Rome carried on the family practice of fostering artists. Pope Leo X primarily commissioned Raphael’s works, although Pope Clement VII requested that Michelangelo decorate the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall just before he passed in 1534. In 1550, Eleanor of Toledo bought the Pitti Palace from Buonaccorso Pitti. Vasari, who built the Uffizi Gallery in 1560 and created the Academy of the Arts of Drawing in 1563, was patronized by Cosimo. Marie de’ Medici is the focus of the renowned cycle, a contracted set of works by royal artist Peter Paul Rubens for the Luxembourg Palace in 1622.

Despite the fact that none of the Medici were scientists themselves, the family is well recognized for being sponsors of Galileo Galilei, who trained many generations of Medici children and served as a key figurehead in his patron’s drive for dominance.

Ferdinando II finally dropped Galileo’s backing after the Inquisition convicted him of heresy. The Medici family, on the other hand, provided the scientist with a safe refuge for many years. Galileo named Jupiter’s four biggest moons after four Medici children whom he trained, albeit the names he chose are not the same as those used today.

Interesting Facts About the Medici Family Members

The Medici family tree is full of interesting characters and events. The Medici family was well-known for their financial skills, but they were also well-known benefactors of the arts. These well-known Florentines went to great lengths to gain power, and they are shrouded in mystery.

They Were Not Nobles

At the very least, they lacked noble blood. The Medici family tree, on the other hand, is rich in knowledge and commercial savvy. And knowing where the Medicis stayed will help you comprehend why they were nicknamed the “Grand Dukes of Tuscany.” They didn’t want their humble beginnings to be remembered, of course. That is why they propagated stories about their ancestors.

According to folklore, the family originated from the deity Perseus. According to another tradition, the family is descended from one of Charlemagne’s knights who vanquished a monster.

The Medicis Had a Personal Mathematician and Alchemist

Francesco di Medici, an alchemist, was a member of the Medici family. Inside the Palazzo Vecchio, he had a secret room called Lo Studiolo, which was furnished with concealed closets full of unusual concoctions and strange artifacts from all over the world. According to mythology, he kept a private closet for a highly prized substance: opium. It’s self-evident that there are some things that money cannot purchase. Unless, of course, you have Galileo Galilei as a personal mathematician, philosopher, and close friend.

Galileo gave the Medician stars to his old student, Grand Duke Cosimo II of Tuscany, a revelation of four celestial spheres that became the ideal method to commemorate the Medici dynasty.

Several Medici Family Members Became Popes

To be precise, four popes were Medicis. Like the rest of his distinguished family, Giovanni di Lorenzo de’ Medici had excellent taste in art. He wanted Michelangelo to help him rebuild and reconstruct St. Peter’s Basilica, but there wasn’t enough funding. That’s why he wrote the “indulgences,” letters that claimed that those who donated to the cathedral were forgiven of their sins in return for money. This approach did not sit well with everyone, particularly Martin Luther, who was rising up against the Church.

Art Preservation Was Valued

Anna Maria, the very last descendant of the Medicis, drafted the “Family Pacts,” which guarantee the conservation of any of the Medici artworks. The artworks, according to the contract, belonged to the state in order to educate citizens about the Medici dynasty and attract international visitors. We may appreciate innumerable masterpieces in Florence, such as the Uffizi Gallery, thanks to this heritage.

The Medicis were an Italian dynasty that controlled Florence and later Tuscany for the majority of the time between 1434 and 1737. Their success in business and banking allowed them to amass money and political influence in Florence. With Cosimo de’ Medici’s ascension to power in 1434, the family’s support for the arts and sciences converted Florence into the center of the Renaissance, a cultural blossoming matched only by ancient Greece. The Medici family produced four popes, and their genes have been carried down through numerous royal dynasties throughout Europe.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Were the Medicis?

Because they laid the groundwork for Florence’s cultural achievement, the Medici family members are recognized as the major characters of the Renaissance. The Medici dynasty is credited with several innovations in art, finance, and architecture that are still in use today. Today, we’ll look at the Medici family’s history and impact, as well as how people like Lorenzo de’ Medici shaped the art world.

For What Is the Medici Family Famous?

Despite being civilians rather than actual royalty until the 16th century, the Medici family’s ascent to power politically in Florence was supported by this institution, which was the largest in the European region throughout the 15th century. The textile trade, which was supervised by Florence’s wool guild, provided the Medici family members with riches and influence. The Medici, like previous Italian dynasties, controlled their city’s administration, were capable of capturing Florence, and created an environment suitable for the flowering of art and knowledge.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Medici Family – Who Were the Medicis, the Famous Art Family?.” Art in Context. June 30, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/medici-family/

Meyer, I. (2022, 30 June). Medici Family – Who Were the Medicis, the Famous Art Family?. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/medici-family/

Meyer, Isabella. “Medici Family – Who Were the Medicis, the Famous Art Family?.” Art in Context, June 30, 2022. https://artincontext.org/medici-family/.