Pitti Palace in Florence – A Look at the Beautiful Florence Palaces

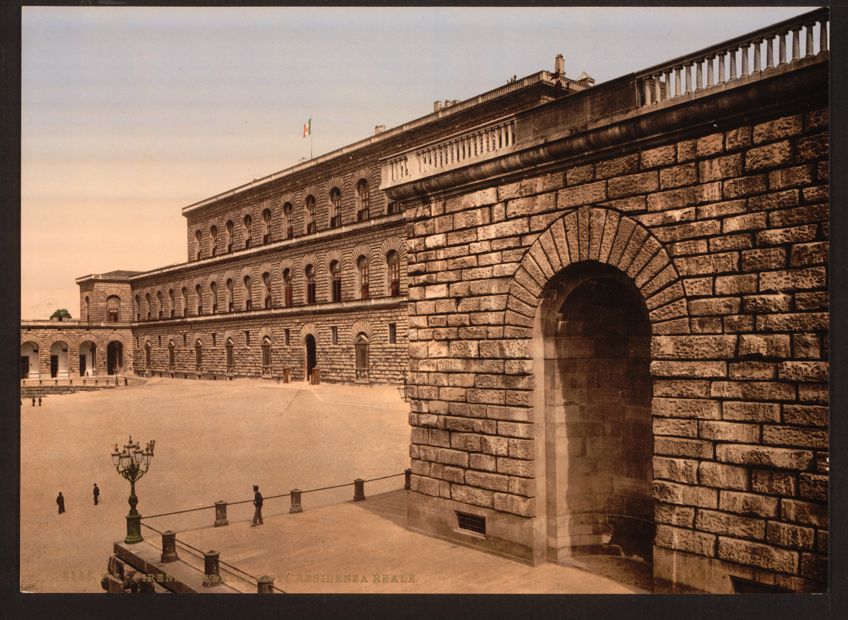

The Pitti Palace in Florence, otherwise known as the Palazzo Pitti, is a vast palace originally constructed in the Renaissance era. In terms of the Pitti Palace’s architecture, the current palazzo originates from 1458 and was once the residence of an enterprising banker from Florence, Luca Pitti. This article will explore the Pitti Palace in Florence’s history, as well as the Pitti Palace’s architecture.

The History of the Pitti Palace in Florence

| Date of Completion | 1458 |

| Architect | Luca Fancelli (1430 – 1494) |

| Function | Palace |

| Location | Florence, Italy |

One of the most significant Florence palaces, the Palazzo Pitti was purchased in 1549 by the Medici family and became the main seat of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany’s governing dynasty. Later generations acquired paintings, dishes, jewels, and opulent items, and it expanded into a vast treasure house. Napoleon utilized the palazzo as a center of power in the latter part of the 18th century, and it afterward served as the major royal residence of the reunified Italy for a short while. King Victor Emmanuel III dedicated the castle and its furnishings to the Italian citizens in 1919. The palace is currently Florence’s largest museum facility. The main palazzo block is organized into numerous major museums or galleries.

Early History

Luca Pitti, The Florentine banker, and a prominent patron and associate of Cosimo de Medici ordered the construction of this austere and intimidating structure in 1458. The Palazzo Pitti’s early history is a blend of reality and fiction. Pitti is said to have ordered that the window frames be bigger than the Palazzo Medici’s entryway. Giorgio Vasari, a 16th-century art historian, claimed that Brunelleschi designed the palazzo and that his disciple Luca Fancelli was only his helper, although Fancelli is now widely attributed.

Aside from noticeable changes in style from the elder architect, Brunelleschi actually passed away 12 years before the palazzo’s construction even began.

The design indicates that the unidentified architect was more familiar with practical household architecture than with Alberti’s humanist standards. The original palazzo, although imposing, would have been no match for the Florentine Medici homes in terms of size or substance. Whoever the Palazzo Pitti’s architect was, he was going against the current trend. The palazzo’s austere and imposing ambiance is enhanced by the multiple arch-headed apertures typically seen in Roman aqueducts.

The Florentine enthusiasm for the style all’antica (in the manner of the ancients), was kindled by the Roman-style buildings. This initial design has endured the test of time: the facade’s repetitious composition was carried over into successive expansions to the palazzo, and its imprint can be seen in various 16th-century renditions and revivals from the 19th century. Work ceased after Pitti incurred financial losses as a result of Cosimo de Medici’s death in 1464. Luca Pitti died in 1472, leaving the construction incomplete.

The Medici Family

Eleonora di Toledo purchased the Pitti Palace in Florence in 1549. Di Toldeo was raised in the opulent court of Naples and married Cosimo I de Medici of Tuscany, who would eventually become Grand Duke. When Cosimo moved into the palazzo, he had Vasari extend it to suit his preferences; the building was more than quadrupled by the erection of a new block at the back.

He also constructed the Vasari Corridor, an above-ground promenade that connects Cosimo’s former residence and the administrative center, the Palazzo Vecchio, to the Palazzo Pitti via the Ponte Vecchio and the Uffizi.

This allowed the Grand Duke and his household to relocate from their official residences to the Palazzo Pitti in comfort and safety. Originally, the Palazzo Pitti was largely used for housing formal dignitaries and rare court ceremonies, while the Medicis’ main house was the Palazzo Vecchio. The palazzo was not used permanently until the administration of Francesco I, the son of Eleanora di Toledo, and his wife Johanna of Austria when it was used to house the Medicis’ collection of art.

Property on Boboli hill behind the palace was bought in order to establish the Boboli Gardens, a huge formal garden, and park. The landscaper hired for this was Niccol Tribolo, a Medici royal artist who passed away the following year and was promptly replaced by Bartolommeo Ammanati. The gardens’ initial concept featured an amphitheater behind the palazzo’s corps de logis. Terence’s Andria was the first play documented as being staged there in 1476. Many classically influenced works by Florentine authors such as Giovan Battista Cini followed.

They were produced for the entertainment of the cultured Medici family and included lavish sets constructed by court architect Baldassarre Lanci.

The Pitti Palace’s Architecture and Surrounding Property

With the garden project completed, Ammanati focused on developing a huge courtyard directly behind the main facade to connect the palace to the new garden area. This courtyard includes channeled rustication that has been frequently imitated, most significantly for Maria de’ Medici’s Parisian Palais, Luxembourg. Ammanati also designed the finestre inginocchiata, which replaced the entry bays at each end of the main facade.

Further Extensions

Ammanati built a magnificent staircase to go to the piano nobile, and he enlarged the wings on the garden front that enclosed a courtyard dug into the steep hillside that was on the same elevation as the plaza in front, which was observable through the basement’s center arch. He built a grotto on the courtyard’s garden side, dubbed it the “grotto of Moses” because of the porphyry figure that occupies it. Ammanati built a fountain that was eventually replaced by the Fontana del Carciofo (1641), designed by Francesco Susini.

A competition was organized in 1616 to propose three-bay additions to the main urban facade at either end.

Giulio Parigi was awarded the commission, and building on the northern side commenced in 1618, followed by Alfonso Parigi on the southern side in 1631. The architect Giuseppe Ruggeri built two additional wings in the 18th century to strengthen and emphasize the expansion of Romana, which forms a plaza centered on the facade, the precursor of the cour d’honneur that was replicated in France. For many years afterward, minor modifications and adjustments were made intermittently by successive kings and architects.

Bernardo Buontalenti constructed the odd grotto on one side of the Gardens. Vasari started the bottom facade, but the upper floor architecture is undercut by pumice stalactites with the Medici’s coat of arms in the center. The interior is equally balanced between nature and architecture; the first chamber features replicas of Michelangelo’s four incomplete slaves positioned in the corners, which appear to hold the vault with an oculus at its center and decorated as a rustic bower with various figures, animals, and vegetation.

The bottom walls are adorned with animals, figures, and trees constructed of stucco and pumice.

The Palazzo Pitti’s Art Galleries

The palace continued to be used as the primary Medici house until 1737 when the final male Medici heir passed. The Medici lineage was rendered obsolete after his sister, the old Electress Palatine, died, and the palace went to the next Grand Dukes of Tuscany, the Austrian House of Lorraine. Napoleon, who utilized the palace during his dominion of Italy, momentarily disrupted the Austrian tenancy.

The Palazzo Pitti was part of the transfer of Tuscany from the Houses Lorraine to Savoy in 1860.

Victor Emmanuel II lived at the palace after the Revolution, when Florence was temporarily the seat of the Kingdom of Italy, until 1871. In 1919, Victor Emmanuel III, his grandson, dedicated the palace to the country. The palace and other structures in the Boboli Gardens were later separated into five independent art galleries as well as a museum, which housed not only many of the palace’s original contents, but also precious artifacts from many other collections purchased by the state.

The 140 public rooms are part of an interior that is mostly a later development than the initial portion of the building, which was generally built in two stages, one occurring in the 17th century and another in the early 18th century. Some early interiors have survived, as have subsequent modifications such as the Throne Room. The unexpected discovery of lost 18th-century bathrooms in the palace in 2005 showed astonishing instances of plumbing extremely close in design to 21st-century bathrooms.

The Palatine Gallery

The Palatine Gallery, Palazzo Pitti’s primary gallery, has a huge collection of approximately 500 mostly Renaissance artworks that were previously part of the Medicis’ personal art collection. Titian, Raphael, Perugino, Correggio, Pietro da Cortona, and Peter Paul Rubens are among the artists represented in the gallery, which spills into the royal apartments.

The gallery retains the feel of a private collection, with artworks exhibited much as they would have appeared in the magnificent halls for which they were designed, instead of following a chronological sequence or being organized by style.

Pietro da Cortona designed the greatest chambers in the high baroque style. Cortona first painted a tiny chamber known as the Sala della Stufa with a sequence representing the Four Ages of Man; the Age of Gold and the Age of Silver were both created in 1637, and the Age of Bronze and Age of Iron were produced thereafter in 1641. They are considered masterpieces by many. Following that, the artist was commissioned to paint the great ducal reception rooms.

The deities’ hierarchical order in these five Planetary Rooms is based on Ptolemaic cosmology.; Venus, Apollo, Jupiter, Mars, and Saturn, but without the Moon and Mercury. The Medici bloodline and the bestowal of moral leadership are fundamentally celebrated in these exceedingly ornate ceilings with paintings and intricate stucco work. Ciro Ferri, Cortona’s pupil, and partner completed the cycle by the 1660s after Cortona departed Florence. They were to be the inspiration for Le Brun’s subsequent Planet Rooms at Louis XIV’s Versailles.

Grand Duke Leopold, eager to gain favor following the Medici’s demise, initially revealed the collections to the general public in the late 18th century, albeit unwillingly.

Palatine Rooms

The Castagnoli Room is named for the artist who created the ceiling frescoes. Various portraits of the Lorraine and Medici reigning dynasties, as well as the Table of the Muses (1851), a masterpiece of the stone-inlaid table made by the Opificio delle Pietre Dure, are displayed in this area. Luigi Ademollo painted the ceiling of the Room of the Ark with Transportation of the Ark of the Covenant in 1816.

The Room of Psyche was designated after Giuseppe Collignon’s ceiling murals and features artwork by Salvator Rosa. Bernardino Poccetti was previously credited with the paintings in the vault of the Hall of Puccetti, but they are now assigned to Matteo Rosselli. A table commissioned by Cosimo III stands in the middle of the hall. There are additional pieces by Pontormo and Rubens in the hall.

The Room of Prometheus was named after the theme of Collignon’s murals and has a huge collection of round-shaped works, two Botticelli portraits, and paintings by Domenico Beccafumi and Pontorma.

The Room of Justice features a frescoed ceiling by Antonio Fedi and portraits produced by Tintoretto, Titian, and Paolo Veronese. Gaspare Martellini frescoed the Room of Ulysses in 1815, and it features early artworks by Raphael and Filippino Lippi. The Madonna Passerini (1526) by Andrea del Sarto and works by Artemisia Gentileschi may be found in the Iliad Room. Raphael’s Portrait of Cardinal Inghirami (1516) and Fra Bartolomeo’s Jesus with the Evangelists (1516) may be seen in the Room of Saturn.

The Veiled Lady (1516), a famous picture by Raphael that, according to Vasari, reflects the artist’s love, is housed in the Jupiter Room. Paintings by Andrea del Sarto, Rubens, and Perugini are among the other paintings in the space. Rubens’ masterpieces dominate the Room of Mars, including allegories illustrating the Consequences of War and the Four Philosophers. A fresco by Pietro da Cortona may be found in the vault.

The Room of Apollo houses a Madonna with Saints (1522) by Il Rosso and two Titian works. The Venus Italica (1810) by Canova, which had been commissioned by Napoleon Bonaparte, is housed in the Room of Venus. On the walls are Salvator Rosa landscapes and four Titian masterpieces. The White Hall, which was previously the palace’s ballroom, is distinguished by its white décor and is frequently used for temporary exhibits.

The Royal Apartments contain 14 rooms in total. The Savoy modified the design to Empire style, while certain rooms still have Medici-era decorations and furniture.

Castagnoli frescoed the Green Room in the early 19th century. It houses a 17th-century intarsia cabinet and a series of gilded bronzes; the throne chamber was designed for King Vittorio Emanuele II of Savoy and is distinguished by red brocade on the walls and Chinese and Japanese vases. The Blue Room houses a collection of furnishings as well as portraits of Medici members of the family produced by Sustermans.

The Royal Apartments

This is a complex of 14 rooms that were originally used by the Medici family and is now used by their successors. These chambers have been significantly remodeled since the Medici time, most significantly in the 19th century. They have a series of Medici portraits, many of which were painted by Giusto Sustermans. In comparison to the enormous salons that house the Palatine collection, a number of these rooms are considerably smaller and cozier, and while still big and gilded, they are more adapted to day-to-day living needs. Four-poster beds and other furniture not seen elsewhere in the palace are among the period furnishings. The Kings of Italy last utilized the Pitti Palace in Florence in the 1920s.

It had already been turned into a museum at that time, but a series of rooms in the Meridian wing was designated for them when they visited Florence on official business.

The Gallery of Modern Art

In 1748, this gallery emerged from the reconstruction of the Florentine academy, at which point a Modern Art gallery was founded. The gallery was designed to house artworks that had won prizes in the academy’s contests. At the time, the Palazzo Pitti was being redecorated on a massive scale, and new artworks were being acquired to ornament the freshly adorned salons. By the mid-19th century, the Grand Ducal’s works of modern art had become so extensive that many were transported to the Palazzo della Crocetta, which was the first location of the newly founded “Modern Art Museum”.

Following Italy’s unification and the removal of the Grand Ducal family from the palace, all of the modern art pieces were housed under one roof at the newly named “Modern gallery of the Academy”. The collection grew in size, especially under the supervision of Vittorio Emanuele II. Nevertheless, it wasn’t until 1922 that this exhibition was relocated to the Palazzo Pitti, where it was supplemented with more modern pieces of art owned by both the monarchy and the city of Florence. The collection was kept in residences that had just been abandoned by generations of the Italian Royal family. The gallery initially opened to the public in 1928.

This huge collection, which has been expanded and distributed over 30 rooms, now contains works by painters from the Macchiaioli school and other contemporaneous Italian schools from the late 19th to early 20th centuries.

The paintings of the Macchiaioli painters are noteworthy because this group of 19th-century Tuscan artists led by Giovanni Fattori was an innovator and creator of the impressionist movement. Some may find the label “gallery of modern art” misleading, considering the work in the gallery dates from the 18th to the early 20th centuries. Since then, no pieces of subsequent work have been added to the collection. “Modern art”, in Italy, actually refers to the time preceding World War II; what followed is commonly referred to as “Contemporary art“.

Treasury of the Grand Dukes

The Treasury of the Grand Dukes, formerly known as the Silver Museum, contains an assortment of cameos, priceless silver, and semi-precious gemstone artworks, many of which are from Lorenzo de’ Medici’s selection, which includes his assortment of ancient vases, many of which had intricate silver gilt mounts incorporated for decorative purposes in the 15th century. These chambers, which were previously part of the royal private apartments, are covered with 17th-century murals, the most magnificent of which was painted from 1635 to 1636 by Giovanni da San Giovanni.

The Silver Museum also has a superb collection of German silver and gold artifacts collected by Grand Duke Ferdinand III upon his return from exile following the French conquest in 1815.

The Porcelain Museum

This museum, which opened in 1973, is situated in the Boboli Gardens in the Casino del Cavaliere. Many of the most well-known European porcelain manufacturers are represented, including Meissen and Sèvres. Many of the pieces in the collection were presents from other European sovereigns to the Florentine monarchs, while others were particularly commissioned by the Grand Ducal court. Several enormous dinner sets by the Vincennes manufacturer subsequently called Sèvres, and a series of miniature biscuit sculptures are noteworthy.

The collection, which contains approximately 2000 items, shows the vicissitudes of Florence’s monarchs during a 250-year span, from the end of the Medici power to the unification of Italy.

The Carriages Museum

This museum can be found on the ground floor and it displays carriages and other modes of transportation used by the Grand Ducal nobility, mostly in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Some of the carriages are very ornate, with not just gilded but also artistic landscapes on their panels. The golden chariot, for example, is surmounted with gilded crowns, which would have represented the status and place of the vehicle’s passengers. The carriages used by the King of Sicily, Archbishops, and other Florentine officials are also on display.

The Costume Gallery

This gallery displays a selection of theatrical costumes spanning the 16th century to the current day. It is also Italy’s only museum dedicated to the development of Italian fashion. Kirsten Aschengreen Piacenti established one of the palace’s younger collections in 1983; the Meridiana apartments, a suite of 14 rooms, were finished in 1858. In addition to theatrical clothes, the collection showcases clothing from the 18th to the present day.

Some of the displays are exclusive to the Pitti Palace in Florence, such as the 16th-century burial garments of Grand Duke Cosimo I de Medici, and his wife and son, who all passed away from Malaria. Their remains would have been shown in state, dressed in their finest garb, before being redressed in simple and plain attire before burial. A collection of mid-century costume jewelry is also on display in the exhibition. The Sala Meridiana (1813) originally featured a working solar meridian instrument, which Anton Domenico Gabbiani included in the fresco design.

Vasari claims that Brunelleschi created the Pitti Palace in Florence, one of the grandest Florence palaces, yet his role in the construction has not been proved. This majestic structure was constructed in the second part of the 15th century. Brunelleschi’s pupil, Luca Fancelli, created this work for Florentine businessman Luca Pitti, a friend and supporter of Cosimo de Medici. Luca Pitti desired to have the most spectacular mansion in the city. Pitti purchased all of the cottages between his new castle and the hill’s walkway in order to build the Boboli Gardens. The vast size of the Pitti Mansion windows was owing to Pitti’s ambition to make them larger than the entryway of the Medici-Riccardi palace. The earliest operas in history were performed in the Boboli Gardens amphitheater. This amphitheater was constructed from the hole created by the excavation of the stone required to erect the palace. Around 100 years later, Eleonora de Toledo, wife of Cosimo I de Medici, purchased the palace, and it was restored and enlarged essentially as we know it now over the next two centuries.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is the Pitti Palace in Florence Used for Today?

In a colossal complex that comprises numerous museums, the Pitti Palace or Italian Palazzo Pitti currently holds notable collections of paintings, sculptures, art objects, costumes, and ceramics. The Palatine Gallery, which was once the Medici gallery, is a beautiful gallery that showcases paintings by Tiziano, Raphael, Rubens, Correggio, and other European Baroque and Renaissance painters. The Modern Art Gallery houses a great collection of sculptures and paintings, primarily by Italian painters, from the 18th century through World War I. Its interior also has works by Italian painters from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

What Are the Boboli Gardens and the Vasari Corridor?

The Boboli Gardens, located behind the Pitti Palace, cover an area of 45,000 square meters and have fountains, grottos, pergolas, a small lake, and hundreds of marble sculptures. The Vasari Corridor connects the Palazzo Vecchio to Palazzo Pitti, one of the achievements that few know about but is accessible to everyone. The Vasari Corridor, sometimes known as the Corridor of Vasari, is a tunnel that runs through the city’s streets. The Vasari Corridor crosses the Ponte Vecchio, which was erected during a junction of Roman times and was Florence’s only crossing across the Arno River until 1218. The current bridge was erected in 1345, following a strong flood that destroyed the old one. The Palazzo Vecchio is an important historical and artistic landmark in Florence. It has served as the city’s political hub and emblem for generations.

Justin van Huyssteen is a freelance writer, novelist, and academic originally from Cape Town, South Africa. At present, he has a bachelor’s degree in English and literary theory and an honor’s degree in literary theory. He is currently working towards his master’s degree in literary theory with a focus on animal studies, critical theory, and semiotics within literature. As a novelist and freelancer, he often writes under the pen name L.C. Lupus.

Justin’s preferred literary movements include modern and postmodern literature with literary fiction and genre fiction like sci-fi, post-apocalyptic, and horror being of particular interest. His academia extends to his interest in prose and narratology. He enjoys analyzing a variety of mediums through a literary lens, such as graphic novels, film, and video games.

Justin is working for artincontext.org as an author and content writer since 2022. He is responsible for all blog posts about architecture, literature and poetry.

Learn more about Justin van Huyssteen and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Justin, van Huyssteen, “Pitti Palace in Florence – A Look at the Beautiful Florence Palaces.” Art in Context. January 13, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/pitti-palace-in-florence/

van Huyssteen, J. (2023, 13 January). Pitti Palace in Florence – A Look at the Beautiful Florence Palaces. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/pitti-palace-in-florence/

van Huyssteen, Justin. “Pitti Palace in Florence – A Look at the Beautiful Florence Palaces.” Art in Context, January 13, 2023. https://artincontext.org/pitti-palace-in-florence/.