Black Death Art – Artworks of the Medieval Bubonic Plague

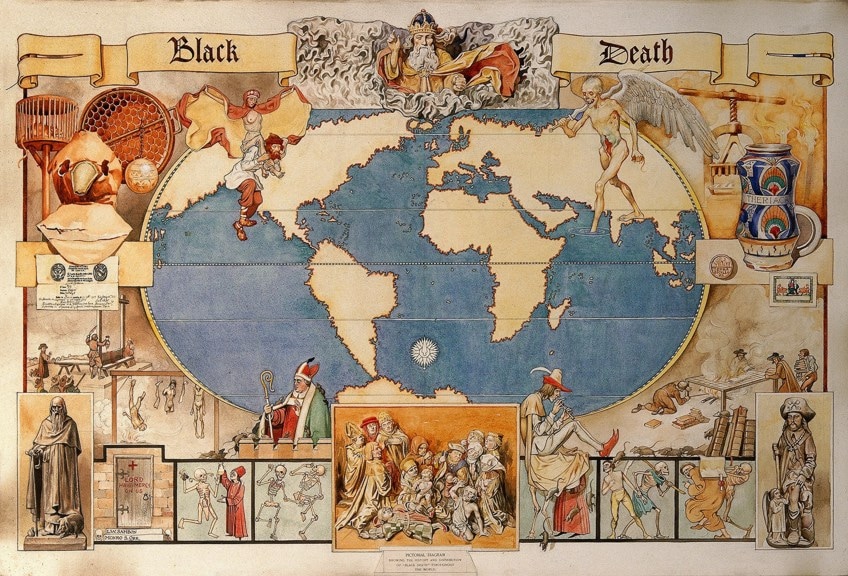

Exactly what effect did the black plague have on art? Throughout the era of plagues, the consequences of such a large-scale common experience on the European populace inspired poetry, literature, theatrical acts, music, and Black Death artwork. Today, we will explore the Black Death paintings from this horrible chapter in human history.

Table of Contents

- 1 Exploring Black Death Art

- 2 Famous Bubonic Plague Paintings

- 2.1 Madonna of Humility (1345-1350) by Guariento di Arpo

- 2.2 Persecution of the Jews (c. 1350) by Gilles li Muisis

- 2.3 Tournai Citizens Burying the Dead During the Black Death (c. 1353) by Pierart dou Tielt

- 2.4 Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (1497-1499) by Josse Lieferinxe

- 2.5 The Triumph of Death with the Dance of Death (c. 15th Century) by Giacomo Borlone de Buschis

- 2.6 Triumph of Death (c. 1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

- 2.7 The Plague at Ashdod (1630-1631) by Nicolas Poussin

- 2.8 Human Fragility (1656) by Salvator Rosa

- 2.9 Doctor Schnabel von Rom (c. 17th Century) by Paulus Fürst

- 2.10 Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804) by Antoine-Jean Gros

- 3 Frequently Asked Questions

Exploring Black Death Art

Artists have frequently attempted to make sense of the unpredictable damage brought on by the Medieval Bubonic plague, creating Black Plague art as a means of expressing their sorrows. Their portrayal of the tragedies they observed has shifted dramatically over time, but the artists’ aim to depict the spirit of an epidemic has stayed consistent.

They have reinvented the disease as something less vague, mysterious, and terrible through these Medieval Bubonic Plague paintings.

An Introduction to Black Plague Art

Throughout much of history, artists have represented epidemics from the perspective of the very religious context in which they lived. Art representing the Black Death in Europe was first interpreted as a warning of the wrath that the disease would bring to sinners and society. The artist took on a new function in the centuries that followed. Their mission was to instill empathy in plague sufferers, who were thereafter connected with Christ, in order to praise and reward the heroic caretaker. Promoting powerful feelings and greater power in fighting the pandemic were strategies to protect and comfort afflicted societies.

Artists developed these artworks to demonstrate how they might withstand and resist the diseases that were happening around them, restoring a feeling of agency.

Artists have battled with notions concerning the impermanence of life, the link to the supernatural, and the duty of carers through their work. At a time when few individuals could read, spectacular visuals with a fascinating plot were produced to attract people and shock them with God’s power in punishing sin with diseases. The plague’s death was viewed not only as God’s punishment for sin but also as a warning that the sufferer would struggle for a lifetime in the world to follow.

What Was the Medieval Bubonic Plague?

Before we go into the Black Death art, here’s a quick rundown of the Bubonic Plague. Throughout the 14th century, the Black Death devastated Europe and Asia. The Medieval Bubonic Plague is caused by Yersinia pestis, a bacterium. Bubonic plague is spread from one host to the next by fleas infected with the virus from other diseased hosts. The 14th century was full of new shipping routes between Asia and Europe, giving rats and fleas easy accessibility to towns and cities everywhere.

The Bubonic plague spread swiftly due to an absence of scientific understanding and sanitary measures, and 20 million people died as a result of the sickness.

The usual symptoms of the sickness include high temperatures, chills, and nausea. Victims, on the other hand, are covered in boils that are ready to burst. After all of these symptoms, the person generally dies within two-seven days of being diagnosed. Despite the fact that a third of Europe’s population was slain throughout the 14th century, individuals continued to produce, including Shakespeare with his play King Lear.

Although romances remained popular throughout the time, the courtly tradition began to encounter increased competition from regular writers who were motivated by their Black Death experiences to produce grim realist writing. That plague completely depopulated villages, cities, castles, and towns, allowing just a few people to dwell there.

The pandemic was so virulent that anybody who touched the dead or the ill became infected and perished, and both were taken to the grave together.

The Emergence of Plague Artworks and the Black Death Paintings

The entire history of Renaissance and Baroque periods in art takes place in the era of plagues. From 1347 through the late 17th century, pestilence gripped much of Europe, with epidemics in southern Europe reoccurring in the 1700s. This meant that the lives of all the “Old Masters” were lived in its shadow: Rembrandt, Michelangelo, and the others all faced the threat of lethal infection at any time. Nonetheless, history is replete with encouraging messages.

People have survived tragedies that contemporary Europeans cannot fathom and come out not only fighting but winning.

Many individuals in the 17th century felt that imagination could either damage or cure. In the midst of an Italian plague outbreak, the artist Nicolas Poussin created The Plague of Ashdod (1631). Dr. Barker feels that in a reenactment of a remote sad biblical scenario that evokes feelings of terror and despair, “the artist meant to safeguard the audience against the exact sickness the picture represents.” Viewers would undergo a cathartic cleansing by raising tremendous emotions for a faraway sadness, immunizing themselves against the misery that surrounds them.

Famous Bubonic Plague Paintings

During difficult circumstances, many creators and entertainers feel compelled to create. What, though, did artwork look like in the 14th century, when Europe was destroyed by the Black Death, and was this mirrored in Medieval art? In this next chapter, we will be looking at a few famous examples of Bubonic Plague paintings. These Black Plague art pieces can provide us with insight into what life must have been like during this extremely tumultuous period.

Madonna of Humility (1345-1350) by Guariento di Arpo

| Artist | Guariento di Arpo (1310 – 1370) |

| Date Completed | 1345-1350 |

| Medium | Tempera on gold and panel |

| Current Location | J Paul Getty Museum, California |

Without the apparition of the Virgin Mary or Madonna, there is no Medieval artwork. Iconographies of Jesus Christ’s mother may be seen in parishes and altars all over the world, and they really characterize religious art. Guariento di Arpo, an Italian artist, produced this panel between 1345 and 1350. Mary is seen seated, nursing the Christ child. She wears a golden crown decorated with diamonds, and over her head is a depiction of God bestowing His benediction on the mother and child.

The moniker “Madonna of Humility” alludes to Mary as a mother figure for those who pray and seek God’s compassion.

The Church capitalized on this susceptibility to encourage more people to convert by emphasizing that if people prayed, went to Church, and repented of their sins, they would not become ill. Of course, this is not true, but it did not prevent people from attending Church, making the Church even stronger than before.

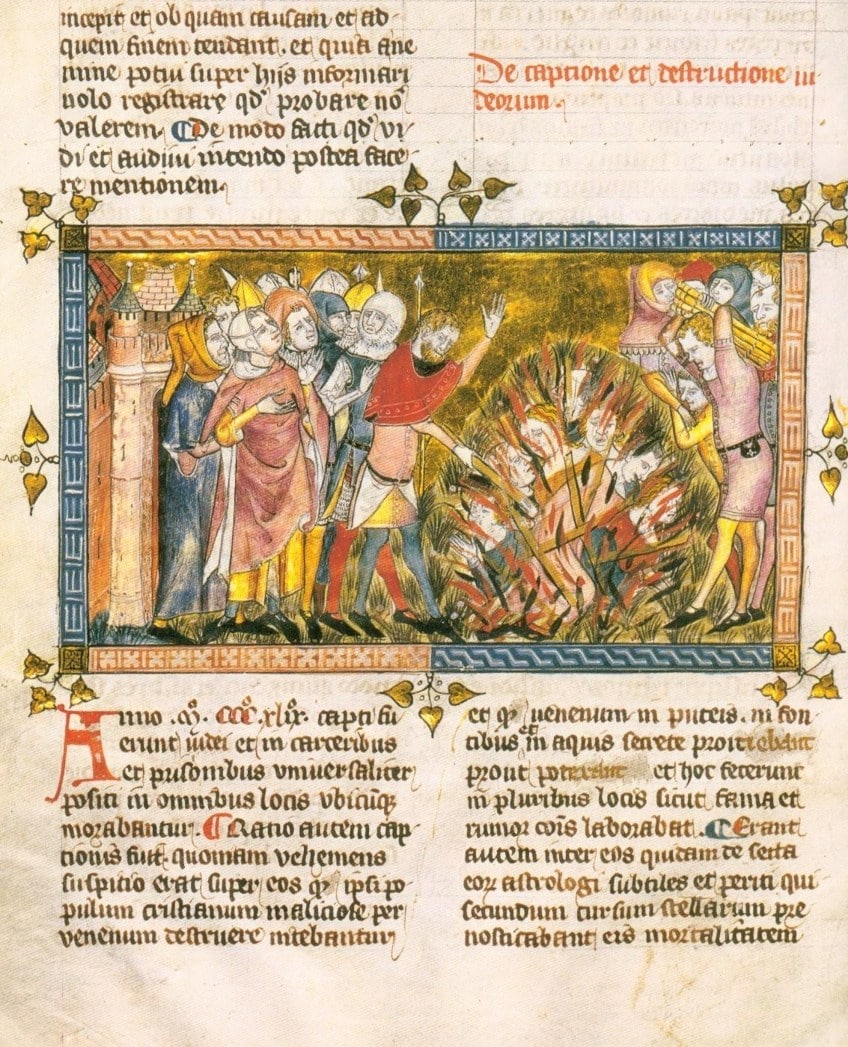

Persecution of the Jews (c. 1350) by Gilles li Muisis

| Artist | Gilles li Muisis (1272) |

| Date Completed | c. 1350 |

| Medium | Manuscript |

| Current Location | Bibliothèque Royale de Belgique, Belgium |

Going to see a local doctor wasn’t the only way Europeans tried to rid themselves of the Black Death. Christians thought that the Jewish people were to blame for the disease’s proliferation. The combination of this plus the Jewish people’s rejection of Jesus as the Messiah enraged God, resulting in the Black Death.

The Jewish population, like many other hypotheses and strategies for eliminating the epidemic, was not accountable for the Black Death and perished at the same rate as European Christians.

This did not prevent Christians from slaughtering their Jewish neighbors. The first massacre happened in France in 1348, and there were soon atrocities all over the continent, one of which is described in this text. In the artwork, Christians burned Jewish people with the aim of satisfying God sufficiently to put an end to the illness. It is unknown how many Jews were murdered, but the dread continued for the duration of the pandemic.

Tournai Citizens Burying the Dead During the Black Death (c. 1353) by Pierart dou Tielt

| Artist | Pierart dou Tielt (b. 1353) |

| Date Completed | c. 1353 |

| Medium | Miniature folio |

| Current Location | Royal Library of Belgium, Belgium |

During the period of the Black Death, people were buried in mass graves, and this painting shows one at Tournai, Belgium. In a very narrow frame, we witness 15 individuals transporting the coffins of their loved ones. Close inspection reveals that the characters’ faces are all distinct and full of expression, which was unusual for Medieval painting at the period (naturalism did not become fashionable until a century later).

Fear and sadness are visible in this art, which was inspired by how individuals felt throughout these times.

This is a scene from a painting in The Chronicles of Gilles Li Muisis at the Belgian monastery of St. Martin the Righteous. Skeletons and death were prominent themes when the Black Death struck. Memento Mori is a phrase in Latin that translates to “remember you must die”. Memento Mori paintings serve as a constant reminder to the audience that death is constantly on the horizon. These pieces were constructed as still lifes using dead flowers, candles that had burned out, clocks, and frightening skeletons.

Memento Mori paintings were most famous in the 17th century and into modernity, but this little artwork shows how delicate mankind is even when we believe we are the strongest species on the earth.

Saint Sebastian Interceding for the Plague Stricken (1497-1499) by Josse Lieferinxe

| Artist | Josse Lieferinxe (b. 1470s) |

| Date Completed | 1497-1499 |

| Medium | Oil on wood |

| Current Location | The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore |

Lieferinxe produced this painting during the Renaissance era, yet it depicts a plague-ravaged town in Pavia, Italy during the 7th century. This was a lesser pandemic that happened years before the iconic Black Death, and it portrays St. Sebastian begging God to help the ill and dying.

Throughout the Black Death, many individuals prayed to St. Sebastian in the hopes of curing the sickness, making St. Sebastian a prominent saint in Medieval art, as shown in the painting below from the chapel of Saint-Crepin-Ibouvillers in France.

During the 300s AD, St. Sebastian served as a Roman military man. He was assassinated with arrows and eventually bludgeoned to death, which is why he is shown in Lieferinxe’s painting with arrows penetrating his flesh.

The Triumph of Death with the Dance of Death (c. 15th Century) by Giacomo Borlone de Buschis

| Artist | Giacomo Borlone de Buschis (1420 – 1487) |

| Date Completed | c. 15th century |

| Medium | Oil painting |

| Current Location | Clusone, Italy |

The Dance of the Dead was a famous and amusing Medieval art motif. The artist portrays individuals from all backgrounds engaged in a dance with skeletons for the Queen of Death, who is positioned right at the top of the piece clutching a pair of scrolls. Two skeletal figures flank her, armed with bows and a gun. The Queen stands on an open casket containing the dead remains of a pope and an emperor, demonstrating that no one is immune to this sickness.

People beneath the Queen of Death implore for clemency while lavishing her with money and presents. But the Queen of Death wants the people’s lives and will take anything she wants. Of course, this does not seem amusing now, yet it was deemed humorous in the 14th century.

Dancing with skeletons to placate Death herself emphasizes how performing arts, such as dancing, did not stop because people died. People sought a means to laugh and have fun before dropping dead where they were.

Triumph of Death (c. 1562) by Pieter Bruegel the Elder

| Artist | Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525 – 1569) |

| Date Completed | c. 1562 |

| Medium | Oil painting |

| Current Location | Museo del Prado, Madrid |

This artwork sees us steer away from the Medieval times, as The Triumph of Death by Pieter Bruegel the Elder depicts the Black Death in a typically European village. The sight of an army of skeletons spreading devastation over a charred, barren landscape has stayed with many to this day. Fires are raging in the distance, and the water is littered with ships. Everything is lifeless, even plants and fish. This artwork represents individuals from many walks of life, from soldiers and farmers to nobility even a monarch and a cardinal.

The message of the artwork was that Death snatches them all without regard to one’s social position or wealth. No one was free from the horrible consequences of the Medieval Bubonic plague.

The Plague at Ashdod (1630-1631) by Nicolas Poussin

| Artist | Nicolas Poussin (1594 – 1665) |

| Date Completed | 1630-1631 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum, Paris |

Paintings representing the epidemic are uncommon because, in the 17th century, it was widely believed that witnessing something like a pandemic in art would have negative bodily consequences. It was believed that if one saw any artwork of illness, they would become afflicted with an outbreak similar to the plague. These widely held views were so powerful that depictions of sickness became extremely disliked.

Poussin’s portrayals of people covering their noses reflect his view during that period that plague victims’ breath may have been contagious, or that the smell coming from dead and ill people was so horrible that others covered their noses to escape the stink.

The hungry infant being taken away from his dead mother’s breasts appears to be depicted appropriately so that the newborn does not become contaminated with the plague from the mother’s milk. These paintings are especially upsetting since seeing the Madonna nursing her breastfeeding baby, a sign of life and protection for Catholics and Christians, would have provided consolation at the time. To witness this infant being taken away from its afflicted mother seemed almost barbaric.

Pestilence may therefore be viewed as unguarded by the Madonna and as potentially fatal.

The man helping the youngster is risking his own life in doing so, demonstrating his bravery. Poussin may have placed this figure there to accentuate the viewer’s intense rage upon viewing the Plague of Ashdod. One challenging figure in this picture is a massive relief of Dagon that has yet to be deciphered.

Human Fragility (1656) by Salvator Rosa

| Artist | Salvator Rosa (1615 – 1673) |

| Date Completed | 1656 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge |

A terrible pandemic raged across Naples in 1655. The artist’s son and brother, as well as his sister and her five children, were all killed by this dreadful epidemic. The woman in this Black Death painting is the artist’s mistress and his son’s mother. The figure of Death has his hand around the artist’s son, clearly indicating that his poor son had died from the plague.

Yet, the more you look at this artwork, the more you will be rewarded since it is filled with symbolism.

Behind his lady, for instance, is a sculpture of Terminus, the Roman deity of Death. The cherubs blowing bubbles represent the shortness of human life, as man’s existence is just a bubble that could be popped at any moment.

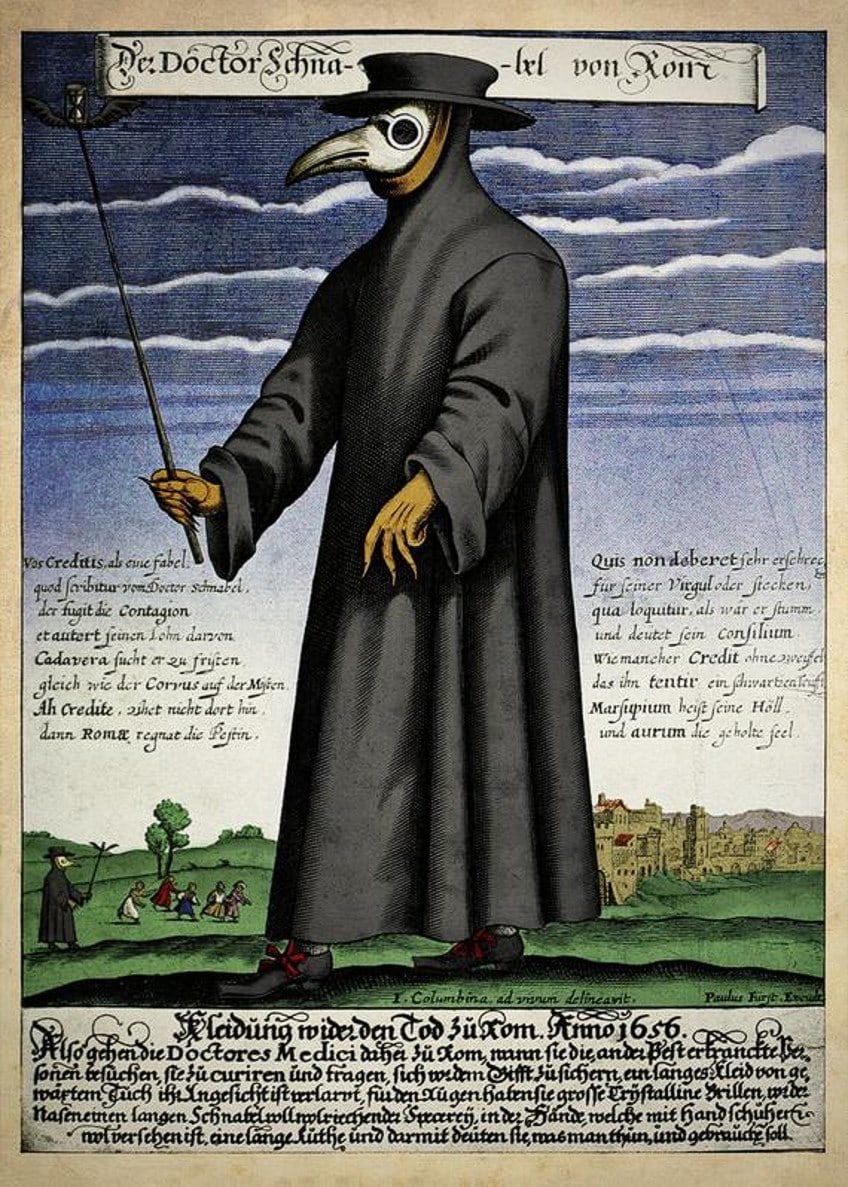

Doctor Schnabel von Rom (c. 17th Century) by Paulus Fürst

| Artist | Paulus Fürst (1608 – 1666) |

| Date Completed | c. 17th century |

| Medium | Engraving |

| Current Location | The British Museum, London |

This etching depicts a 17th-century protective garment worn in France and Italy. It worried people because it represented impending death. It was made up of an ankle-length coat, a bird-like snouted mask, gloves, boots, gloves, a hat, and another layer of clothes. These masks included glass eye holes and a strap that kept the beak-shaped mask in front of the doctor’s nose. The mask also featured two small nose openings and was a form of early respirator that contained sweet or pungent odors. In addition, the beak might store dried flowers, spices, herbs, or camphor.

The mask’s objective was to keep foul odors, known as miasma, at bay, which were considered to be the major cause of the ailment. This was later confirmed by germ theory.

Bonaparte Visiting the Plague Victims of Jaffa (1804) by Antoine-Jean Gros

| Artist | Antoine-Jean Gros (1771 – 1835) |

| Date Completed | 1804 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum, France |

The seizure of Jaffa by the French army led by Bonaparte on the 7th of March 1799 was quickly followed by an epidemic of bubonic plague, which was discovered by January 1799 and destroyed the troops. On the 11th of March, Bonaparte paid a visit to his ill men and even touched them with his own hands, which was seen as either spectacular or fatal, depending on one’s perspective on Napoleonic legend or epidemic terrors.

The Napoleonic army sought the assistance of monks from the Armenian monastery, who supplied medicine that cured some of the troops.

Napoleon honored the Armenian patriarch personally and presented him with his own camp and weapons. The picture was commissioned by the state when Napoleon became Emperor, and it had an obvious propaganda function. In terms of eyewitnesses, there is no indication of such an occurrence in General Berthier’s campaign report. Bonaparte’s private secretary, Bourrienne, simply stated that the commander crossed the lazaretto quickly. Doctor Desgenettes, on the other hand, said that Bonaparte seized the ill and assisted in their transportation. It is now established that the disease is not spread by contact.

With that, we conclude our look at the Black Death artworks that captured the essence of life during a deadly plague. We have seen that even in periods of extreme suffering, artists have found a way to express their feelings through their Black Death art. All of the Black Death paintings above have served as reminders of a time when humankind suffered greatly from the Medieval Bubonic Plague.

Frequently Asked Questions

Exactly What Effect Did the Black Plague have on Art?

The second plague outbreak, which occurred in the mid-14th century, had a tremendous impact on European culture, the concept of death, and theology. Many creative portrayals of this period depicted moments of horrific misery, satire, and at times – hope. This era was frequently defined by death and its numerous, ever-changing manifestations.

What Are the Specific Characteristics of Black Death Artwork?

The Black Death left an evident sense of misery and sadness in its wake. This sadness was expressed in a variety of cultural and creative forms. During that period, creative expression mirrored people’s personal experiences with death. The disease began swiftly decimating Europe’s population, with no apparent cause. People started believing that death from the plague was the consequence of God’s punishment and foreshadowed an eternity of misery since it was a time of intense religious belief and superstition. The Black Death firmly established realism in the arts. Most artworks of the period attempted to depict the triumph of death over their naïve victims, but in some cases also the bold defiance of people’s pride.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, “Black Death Art – Artworks of the Medieval Bubonic Plague.” Art in Context. August 10, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/black-death-art/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 10 August). Black Death Art – Artworks of the Medieval Bubonic Plague. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/black-death-art/

du Plessis, Alicia. “Black Death Art – Artworks of the Medieval Bubonic Plague.” Art in Context, August 10, 2022. https://artincontext.org/black-death-art/.