Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography

Michelangelo Buonarroti is considered by many to be among the most significant luminaries in the history of art. But, what is Michelangelo famous for and what did Michelangelo study? Michelangelo was one of those incredibly talented people that excelled in multiple disciplines, and was renowned for his sculptures, architecture, and paintings. To find out more about this fascinating Renaissance man, let’s take a deeper look at Michelangelo’s biography, as well as address some common questions on the topic, such as, “where did Michelangelo live?”, “was Michelangelo married?”, “how did Michelangelo die?”, and “how old was Michelangelo when he died?”.

Exploring Michelangelo’s Biography

| Artist Name | Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Date of Birth | 6 March 1475 |

| Date of Death | 18 February 1564 |

| Place of Birth | Caprese, Arezzo, Florence, Italy |

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born in Caprese, a little village close to Arezzo. He came from a middle-class background and his father was a banker. His mother had suffered for many years from an illness which unfortunately took her life when the young Michelangelo was only six years of age. His father had no choice but to leave him in the care of his nanny as he did not have the time to raise him. The nanny’s husband was a stonecutter by trade and it is believed that this is where the young artist’s passion for marble first began.

Childhood and Early Training

Even at the age of 13, it was apparent to Michelangelo’s father that the young boy had no desire to follow the family trade of banking and so he was sent to Domenico Ghirlandaio’s studio to serve as his apprentice. This studio would be the perfect place for the aspiring artist to pick up all the necessary techniques and tricks of the trade, with Ghirlandaio possessing a thorough knowledge of draftsmanship and fresco painting techniques. However, it is believed that Michelangelo found that his personal views on art often clashed with those of his mentor, and he preferred to study the works of the masters such as Donatello, Masaccio, and Giotto than follow Ghirlandaio’s methods. He had only been working at the studio for around a year when the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de’ Medici, asked Ghirlandaio to let Michelangelo and Francesco Grancci (his two best students) join his Humanist academy.

In Renaissance Florence at this time, new ideas and philosophies were starting to emerge and artists were encouraged to study the humanities in order to supplement their artistic works with an understanding of ancient Greco-Roman art and philosophy.

The more progressive artists were establishing a Renaissance style that would promote humanist principles and recognize man’s essential role in creating the modern world, moving away from Gothic imagery and devotional works. While there, Michelangelo Buonarroti trained under Bertoldo di Giovanni, the bronze sculptor, who exposed him to the iconic classical statues in the Lorenzo Palace. Michelangelo, like Leonardo da Vinci, was not content with studying the principles of anatomy from classical sculptures. He undertook his own studies into human anatomy, dissecting corpses, and sketching from models until he got to the point where the human body no longer held any mysteries for him, and he felt like he quite literally knew the human body inside-out.

Yet, he differed from da Vinci in the fact that anatomy was just one riddle to be figured out of many for the other artist, whereas for Michelangelo, it was the single most important problem that he wanted to master above all others. Around this time, he received the necessary permission from the friars of Santo Spirito Church to examine corpses in the convent’s hospital, where he would acquire a thorough grasp of the anatomy of humans. After Lorenzo de’ Medici passed away in 1492, the 17-year-old Michelangelo found himself without a patron and was offered shelter in the monastery. Michelangelo produced a strikingly life-like wooden sculpture that hung over the main altar out of gratitude. It was reported as lost after the French conquest in the late 18th century, although it had actually been transported to another church and painted to conceal its identity.

Early Work

The Republic of Florence was threatened with siege by the French in 1494. Concerned about his safety, Michelangelo relocated to Bologna, with a brief detour in Venice. In the city, he met Giovan Francesco Aldrovandi, a rich Bolognese senator who was successful in obtaining the commission for the outstanding statuettes for the marble tomb lid for the Arca of St. Dominic for Michelangelo. The original lid was produced by Niccolo dell’Arca in 1473, with Michelangelo carving the few surviving figures in 1496, including Saint Petronio, Saint Proculus, and an angel with candles.

Michelangelo, who was still just 19 years old at the time, eclipsed the production of the elder sculptor with his unprecedented detail in the folds of the linen and fabric, and in the form of Petronio, to whom he added a palpable feeling of motion by depicting him in mid-step.

Time in Florence

Once the risk of a French invasion passed, Michelangelo temporarily returned back to Florence. He was working on two sculptures: one of St. John the Baptist and another depicting a cupid. Cardinal Riario of San Giorgio bought the sculpture after being deceived into thinking it was actually an antique statue. Despite his initial anger upon learning about the deceit, Cardinal Riario was rather impressed by the young sculptor’s talent and summoned him to Rome to start on a new project. Michelangelo sculpted a figure of the Roman god of wine, Bacchus, for the commission, which was ultimately rejected by the Cardinal, who felt it was politically inappropriate to be affiliated with a nude pagan figure. Michelangelo, who had by that point gained notoriety for being temperamental, was enraged and told Condivi, his biographer, years later to instead record it as an order from his banker, Jacopo Galli, the man who ultimately bought the finished sculpture.

Time in Rome

After finishing the statue, Michelangelo stayed in Rome, and Cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas ordered his Pietà for the chapel in Saint Peter’s Basilica for the King of France. “Pietà” was actually a generalized label assigned to devotional works aimed to encourage worshippers to participate in penitent prayer, but Michelangelo’s piece was its most renowned interpretation. Michelangelo’s sculpture was unique in that he created two characters from a single piece of marble. Additionally, his presentation of his figures, which highlighted the artist’s attention to emotion and naturalism, earned Michelangelo considerable praise and new followers. Despite the fact that his reputation as one of the most divinely talented individuals of the time was assured, Michelangelo failed to secure any big assignments for another two years.

Yet, he was not particularly concerned about a lack of employment or financial stability.

“No matter how affluent I may have been, I always behaved like a poor man”, he would declare to Condivi at the end of his life. Girolamo Savonarola, a Florentine puritanical monk, would become notorious in 1497 for his Bonfire of the Vanities, an occurrence in which he and his followers publicly destroyed paintings and books. Their behavior disrupted what had been a flourishing era of Renaissance culture. Michelangelo did not return to Florence until Savonarola was deposed a year later. In 1501, he received an order from the Guild of Wool to finish an incomplete project started four decades earlier by Agostino di Duccio.

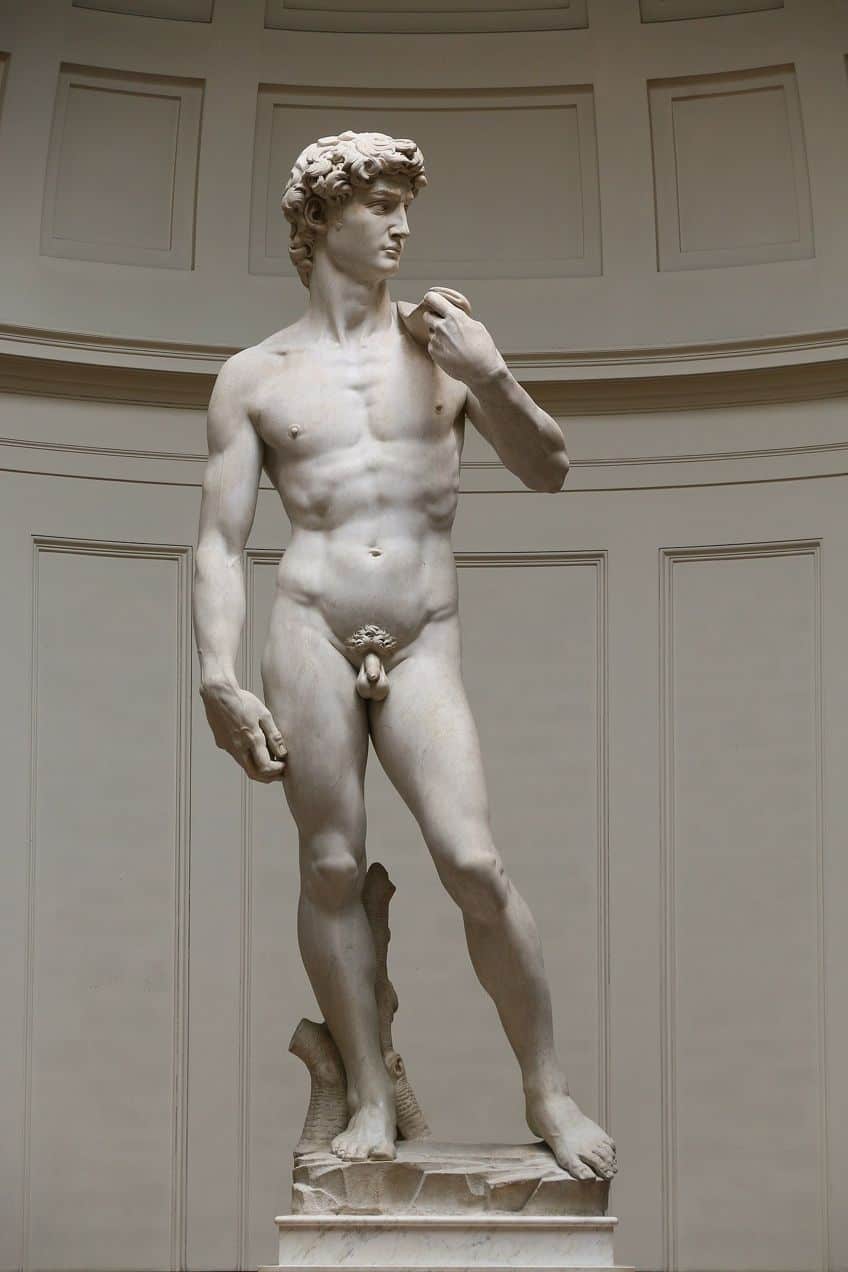

The Making of David and Other Works

The 17-foot-tall naked figure of the scriptural hero David was completed in 1504. The piece was a testament to his unmatched talent in sculpting strikingly lifelike human beings out of cold marble. It has become the definitive symbol of the Renaissance concept of ideal humanity. Even though the artwork was initially planned for the cathedral’s buttress, the grandeur of the completed project persuaded Michelangelo’s peers to set it in a more significant location, to be decided by a committee of artists and influential figures. They opted to place the statue in front of the Palazzo Vecchio’s entryway as a representation of the Florentine Republic. Upon the iconic sculpture’s completion, he received numerous painting commissions.

Doni Tondo (1504) is the only painting of Michelangelo known to survive to the present day. Scholars believe the artwork reveals the artist’s infatuation with Da Vinci’s works. They claim that Michelangelo repeatedly denied being influenced by anybody, and his comments were typically accepted without question. However, Da Vinci’s return to Florence following almost two decades was exhilarating to the city’s younger artists, and later academics typically accepted that Michelangelo was among those artists influenced by his output. Competition between Michelangelo and his contemporaries was strong throughout the High Renaissance in Florence, with painters all competing for the same commissions.

Rivalries

Da Vinci was considered to be the most notable individual of the whole Florentine brotherhood of Renaissance masters and 23 years older than Michelangelo. Yet an unstated rivalry between the two artists was well recognized. Piero Soderini commissioned both painters to paint opposite walls of the Palace Vecchio’s Salone dei Cinquecento in 1503. It was a momentous time in art history when these two titans contended for the palm, and everyone in Florence observed their preparatory efforts with eager anticipation. Unfortunately,

Soderini abandoned the project, and neither of the artworks were ever completed. Da Vinci traveled to Milan, while Pope Julius II summoned Michelangelo to Rome.

Mature Period

When in Rome, Michelangelo began work on the Pope’s tomb, a gigantic mausoleum that was scheduled to be finished in five years. After visiting the famed Carrara quarries, he spent six months carefully searching for the ideal blocks of marble from which to create his figures. To his great disappointment, Julius summoned Michelangelo to Rome, where he heard that the structure designated to hold the tomb was to be demolished and the undertaking as a whole halted. Michelangelo was enraged and believed that there was some kind of plot to destroy him. He even suspected that Bramante, the new St. Peter’s Basilica’s architect, was plotting to poison him. Michelangelo then returned to Florence, enraged, and penned a letter to the Pope, voicing his indignation at his mistreatment in Rome.

The Sistine Chapel

The artist found himself in the midst of a complex diplomatic struggle between Rome and Florence. The head of the Florence city government convinced Michelangelo to return to Julius II’s employment and provided him with a recommendation letter in which he stated that his art was unparalleled across the whole of Italy, possibly even throughout the whole world. After creating a massive bronze figure of the pope for the recently acquired city of Bologna (which was abruptly demolished after papal invaders were defeated),

Julius commissioned Michelangelo to finish a project begun by Ghirlandaio, Botticelli, and others.

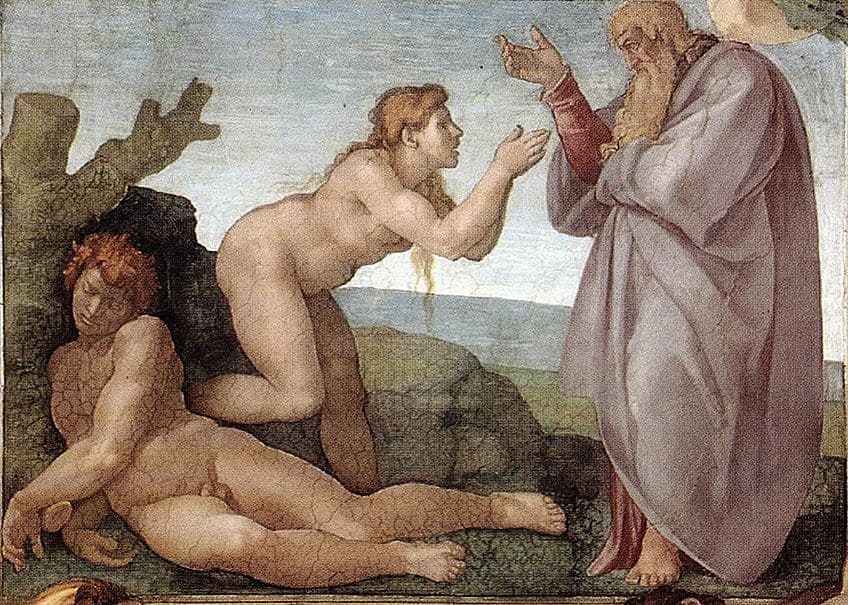

The assignment was to create frescoes for the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, and it is believed that Bramante persuaded the Pope that Michelangelo was the ideal person for the task, despite the fact that Michelangelo was primarily recognized for his sculptures and hence almost certainly would not succeed in this massive endeavor. Michelangelo would spend the next four years working on the Sistine Chapel. He painted the ceiling while lying on his back on a scaffold structure made from wood, with only one assistant to mix the paint. What emerged, though, was a significant work of incredible talent depicting Old Testament narratives.

The completed painting, which featured multiple naked individuals (an unusual sight at the time), would ultimately become a magnificent masterwork of artistic expression. After completing the Sistine ceiling, he went back to working on the initial project for Pope Julius’ tomb. After the passing of Pope Julius II in 1513, financing for his tomb came to a halt, and the artist was assigned by the new Pope Leo X to start working on the Basilica San Lorenzo’s façade, Florence’s largest church. Michelangelo worked on it for the next three years before abandoning it because of a shortage of funding. Cardinal Giulio de’ Medici ruled Florence at the time, and the two men had a strong professional connection. Actually, under the Cardinal, Michelangelo enjoyed considerable creative freedom, which enabled him to venture deeper into the sphere of architectural design.

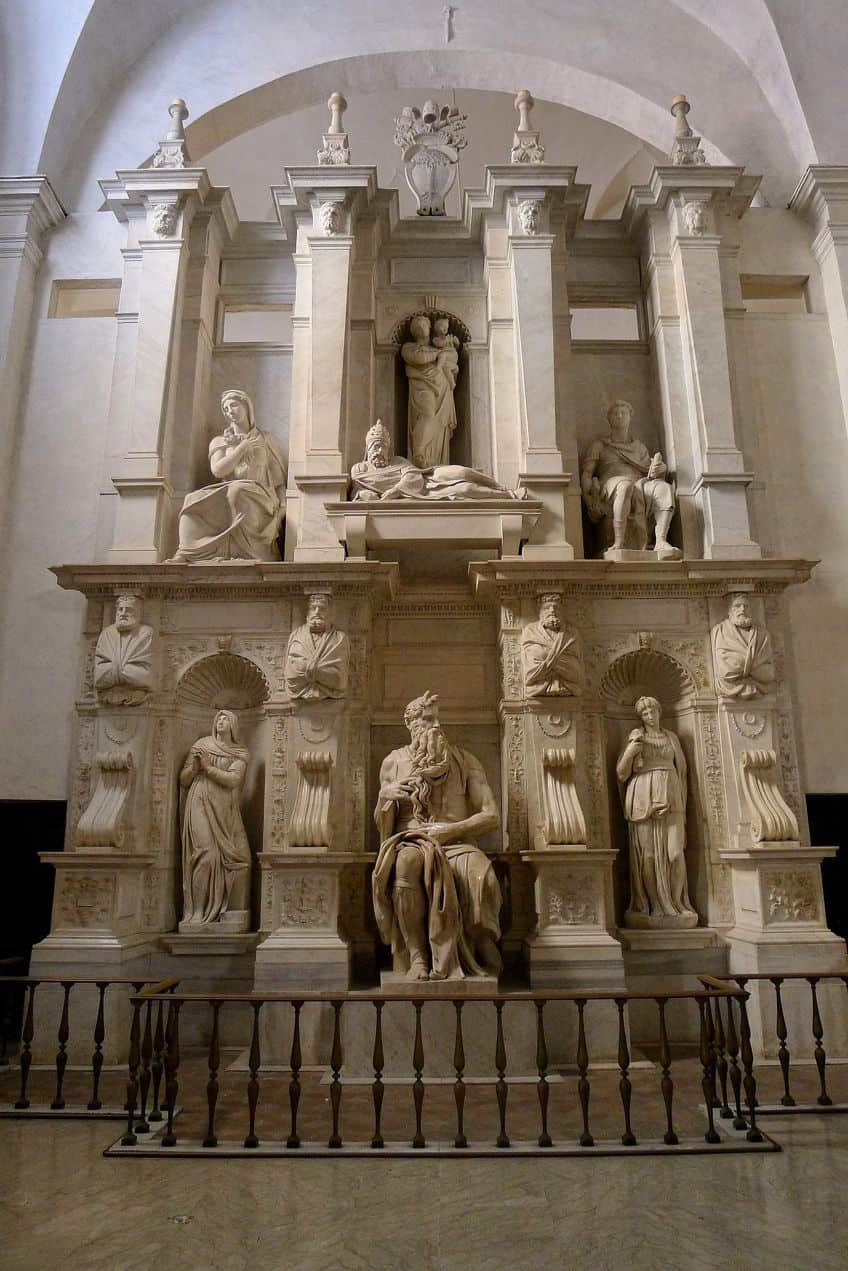

Julius II’s Tomb

Florence was proclaimed a republic following the conquest and pillage of Rome by Charles V’s forces in 1527. Nevertheless, the city was besieged in October 1529 before eventually falling in August 1530. The Medici family was reinstated to authority in the city by a new accord between Charles V and Pope Clement VII. After building defense structures for the fortification of Florence, Michelangelo was re-hired by Pope Clement, who offered him a new contract to resume work on Pope Julius II’s tomb. Michelangelo turned to fresco painting once more in Rome, this time for Pope Paul III. In 1534, he returned to the location of one of his greatest accomplishments, painting a huge and vibrant redemption tale for the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall.

The Last Judgment, with its concept of Jesus’ “second coming,” was part of Roman Catholic teaching’s great narrative, and it took him seven years to complete.

Late Period

Toward the end of his career, Michelangelo began to focus more on architectural designs, and his most recognized work is St. Peter’s Basilica. Pope Julius II suggested removing the existing Basilica and replacing it with the “greatest structure in Christendom”. While Donato Bramante’s design was selected in 1505, and foundations were constructed the year after that, minimal progress had been made since. Michelangelo was in his 70s when he hesitantly took over the project from his rival (Bramante) in 1546, claiming, “I do this solely for the love of God and in reverence of the Apostle”. He continued working on the Basilica as Chief Architect for the remainder of his existence.

His most significant contribution to the design was his work on the dome at the Basilica’s eastern end. Except for the initial plans of Bramante, who had also envisioned an edifice to rival even Brunelleschi’s iconic dome in Florence, he disregarded all preceding architects’ ideas on the project. While the dome was not completed until after his passing, the foundation on which the dome was to be put was constructed, ensuring that the final draft of the dome remained loyal to Michelangelo’s grandiose vision.

The dome, which is still the biggest cathedral in the world, is both a Roman landmark and a tribute to Michelangelo’s eternal bond with the city.

Michelangelo’s final paintings, completed between 1542 and 1550, were a series of frescoes for the Vatican’s private Pauline Chapel. One of these works, The Crucifixion of St. Peter (1550), includes a horseman with a turban, and conservators and scholars think that this was actually a self-portrait. He also kept sculpting but did so privately for his own enjoyment. He finished a number of Pietàs, including the Deposition (1547), (which he actually tried to destroy) and his final work, the Rondanini Pietà (1564), on which he worked until his eventual death.

In his late years, the artist appears to have withdrawn more and more into himself. The poetry he composed indicates that he was tormented by uncertainties as to whether his artwork had been as sinful as others had accused it of being, while his letters made it obvious that the higher he gained in favor in the world, the more unpleasant and caustic he became. His infamous temper not only left others in awe but also in fear. His intensely private and reserved demeanor, including an instance where, while painting the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, he flung wooden boards at a passing Pope who he had confused for a spy, indicates he battled from bouts of paranoia.

The Legacy of Michelangelo

What is Michelangelo famous for? Michelangelo was regarded as the absolute master of sculpting when it came to the human form, which he accomplished with so much technical flair that his marble almost appeared to transform into life. Scholars have noted his influence on the works of other masters such as Peter Paul Rubens, Raphael, and Gian Lorenzo Bernini, as well as Auguste Rodin, considered to be the last great sculptor to follow Michelangelo’s realist manner. Michelangelo has always been regarded as among a very small group of creative minds that were able to express the deepest and most tragic of human emotions to a degree of universal scope, along with other luminaries such as Beethoven and Shakespeare. And although the works of artists in this group were highly revered, they were seldom replicated and their subsequent influence was rather limited.

This was not because the artwork was regarded as too difficult to try and emulate – in fact, Raphael was regarded in the same light as Michelangelo as far as abilities are concerned, yet he was emulated much more by subsequent artists.

It appears that it was his particular style (that aspired to a “cosmic grandeur”), which artists found creatively inhibiting, and therefore did not try to mimic, except for a few artists such as Daniele de Volterra, who fully embraced his style. Rather, there were specific elements of his work that were embraced by certain movements. He was considered to be a master of anatomical drawing in the 17th century, for example, yet they found other aspects of his art lacking. Yet, while his influence may not always be so apparent or obvious, there is no doubt that his work had a very significant impact on the world of art.

Notable Artworks

Many consider Michelangelo’s ability to carve a figure (sometimes multiple figures) out of a single block of marble to be unmatched by any other sculptor. Yet, in addition to being so well-renowned as a sculptor, his artistic abilities knew no bounds, and he also created one of the most iconic frescoes in the history of art – the paintings on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. That’s not even mentioning his world-famous architecture! Here are a few of his most notable artworks.

| Artwork | Date Completed | Medium | Dimensions (cm) | Location |

| Bacchus | 1497 | Marble | 203 | National Museum of Bargello, Florence, Italy |

| Pietà | 1499 | Marble | 174 x 195 | Vatican City, Rome, Italy |

| David | 1504 | Marble | 517 x 199 | Gallery of Academy of Florence, Italy |

| Doni Tondo | 1506 | Oil and tempera | 120 | The Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy |

| The Creation of Adam | 1512 | Fresco | 280 x 570 | Sistine Chapel, Vatican City |

As we have discovered through our exploration of Michelangelo’s biography, he was an extremely talented yet temperamental individual who was determined to unravel all the secrets of human anatomy so that he could accurately depict our form in his famous sculptures. His talent was also the source of much paranoia in his life, often believing that someone was out to destroy him and his career. Despite his increasingly reclusive nature over the years, he was often called upon to produce works – many of which that have become some of the most iconic pieces in the history of art.

Frequently Asked Questions

How Did Michelangelo Die?

It is believed that Michelangelo Buonarroti passed away due to a combination of issues with his kidneys and a simultaneous fever. Yet, despite his deteriorating condition, he worked right up to his death. He was even preparing sketches for new projects just before he passed away.

How Old Was Michelangelo When He Died?

The renowned sculptor and artist, Michelangelo Buonarroti, was 88 years of age when he eventually passed away. He died on the 18th of February 1564, following a prolonged illness that affected his kidneys and a serious fever. He was an active artist even in the final years of his life.

What Did Michelangelo Study?

From a young age, Michelangelo apprenticed under a series of various artists, such as Domenico Ghirlandaio, whom he first worked under when he was 13 years of age. He also took it upon himself to learn about human anatomy by dissecting corpses. He also studied humanities for a while at the De Medici Academy in Florence.

Was Michelangelo Married to Anyone?

No, Michelangelo Buonarroti is not known to have married anyone throughout his life, and it is not even known if he ever had any romantic relationships. There were many rumors that he was actually gay, much of which could be backed up by his own writings, which were apparently very homo-erotic in nature. Yet, his main love was his art, and this is where all of his attention and devotion went to. However, we do know that he enjoyed the company of close friends, several of whom he was particularly fond of and confided in.

Where Did Michelangelo Live?

Michelangelo Buonarroti first grew up in Caprese in Florence, near Tuscany. Many of his famous works were created while living in Florence, such as David. He also spent a considerable amount of time in Rome, living and working on various projects such as the Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo would continue to move depending on where he was commissioned to go, or sometimes based on political events where he no longer felt safe to stay where he was. He spent a fair amount of time in Venice, working on the Virgin Mary and Child sculpture. Several years were also spent in Bologna working on St. Dominic’s tomb, and he also spent time selecting marble for his sculptures in places such as Carrara.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography.” Art in Context. June 1, 2023. URL: https://artincontext.org/michelangelo-buonarroti/

Meyer, I. (2023, 1 June). Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/michelangelo-buonarroti/

Meyer, Isabella. “Michelangelo Buonarroti – A Detailed Michelangelo Biography.” Art in Context, June 1, 2023. https://artincontext.org/michelangelo-buonarroti/.