Aesthetic Movement – Art Created for Pure Visual Pleasure

What was the Aesthetic movement? The intriguing and sensual Aestheticism movement sought to demolish Britain’s pompous, domineering, and orthodox Victorian customs in the mid-19th century. Aesthetic art styles influenced everything from literature and music to fashion and interior design and were more than just a fine art trend. The Victorian aesthetic movement aimed to elevate tastes, the exploration of beauty, and self-expression above moral standards and oppressive compliance.

An Introduction to the Aesthetic Movement

The liberation of artistic expression and pleasure that the 1800s aesthetics encouraged enthralled its followers, but it also made them the laughingstock of traditional Victorians. Nonetheless, aestheticism paved the way for worldwide, 20th-century contemporary art by abandoning art’s typically instructional duties and emphasizing self-expression.

Victorian Aesthetic painters, in defiance of the era’s materialism and contemporary industrialism, placed an emphasis on superior workmanship in the production of all art. In the end, some even resurrected pre-industrial processes.

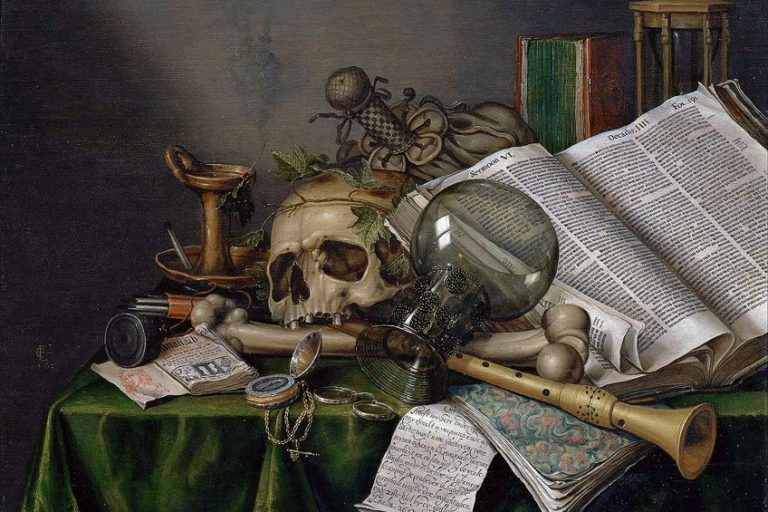

1800s Aesthetic artists liberated art from its customary responsibility to communicate an ethical or sociopolitical statement. Rather, they concentrated on the quest for beauty via colors, structure, and composition. Aesthetic art is distinguished by geometric patterns, muted colors, and reduced linear shapes, as opposed to the Victorian propensity for elaborate ornamentation, curvy forms, and rich detail. Medieval geometric patterns, pre-Raphaelite images of blazing red-haired heroines, and Japanese themes and aesthetics served as key points of influence for the Aesthetic movement.

The Roots of Aestheticism

1851’s Great Exhibition was a watershed moment in British visual arts. Despite the fact that the expo featured key recent breakthroughs, like the visual technique of photography, much of the art on display adhered to the Victorian age’s precise and superficial design approach. Furthermore, the machinery of the creative process resulted in the dehumanization of style, according to renowned critic John Ruskin.

These formulaic, repetitious motifs, along with rigorous Victorian art rules that valued the ethical message expressed over the excellence of the piece, created a suffocating atmosphere from which many creators yearned to depart.

Pre-Raphaelite Inspiration

Shortly after the Great Exhibition, a group of painters set out to create a new, simpler style, one that was influenced by medieval art and design’s rich detail and vibrant colors. By the 1860s, the work of the so-called pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood had acquired appeal, due in part to John Ruskin’s positive evaluations.

After that, the group separated when younger painters, such as Edward Burne-Jones, joined Dante Gabriel Rossetti to form a “Cult of Perfection,” which laid the groundwork for Aestheticism. Rossetti’s sensuous images of unconventionally attractive ladies with huge eyes and fiery red hair draped in loose, flowing dresses challenged Victorian preconceptions linking non-corseted, red-haired women with sensual decadence, and became a prominent theme of the Aesthetic movement.

Japanese Inspiration

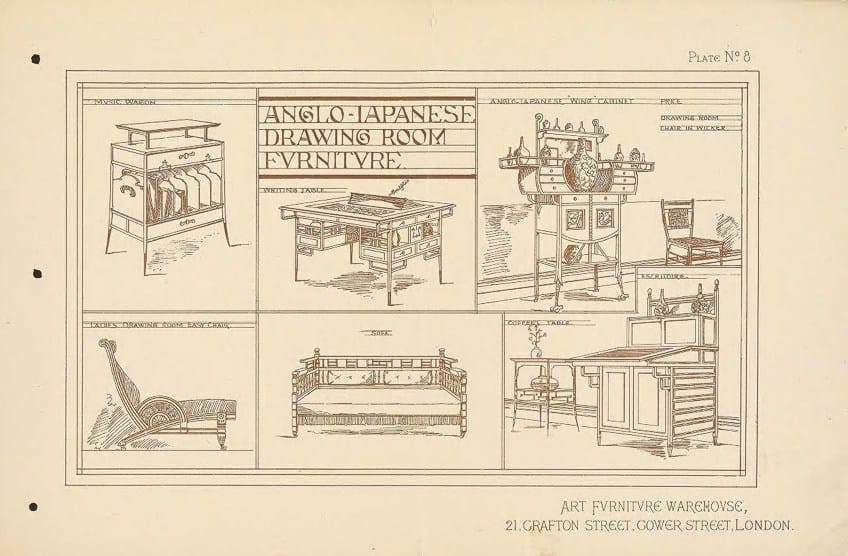

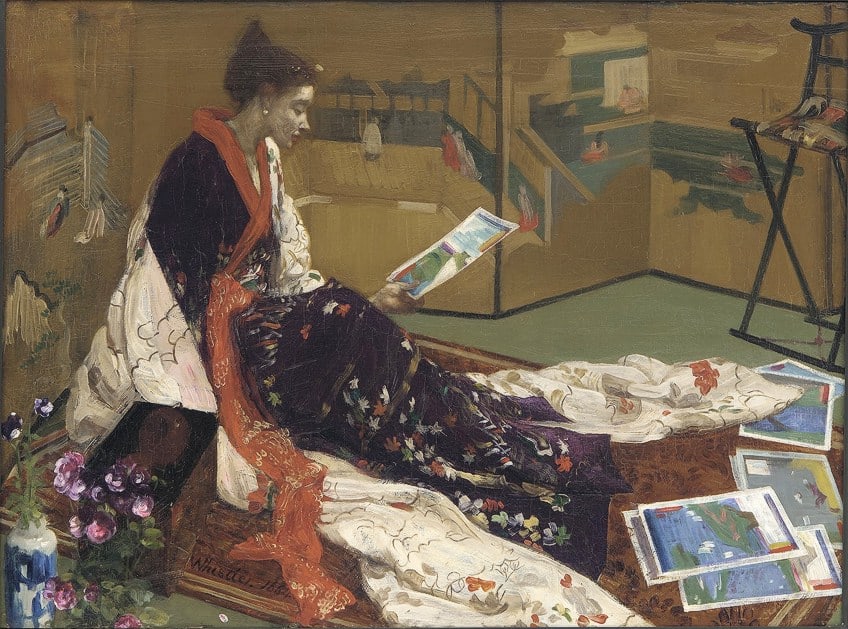

Japan’s exports swamped the British marketplace when it started publicly dealing with foreign nations in 1854. The stylized organic themes, circular forms, and geometric patterns that marked this new style charmed both artists and customers. Its simplicity and grace of form contrasted strikingly with Victorian styles that were congested and busy.

Consumers in the United Kingdom started gathering Japanese screens, fans, and ceramics, as well as coloring their furniture black to resemble Japanese lacquer.

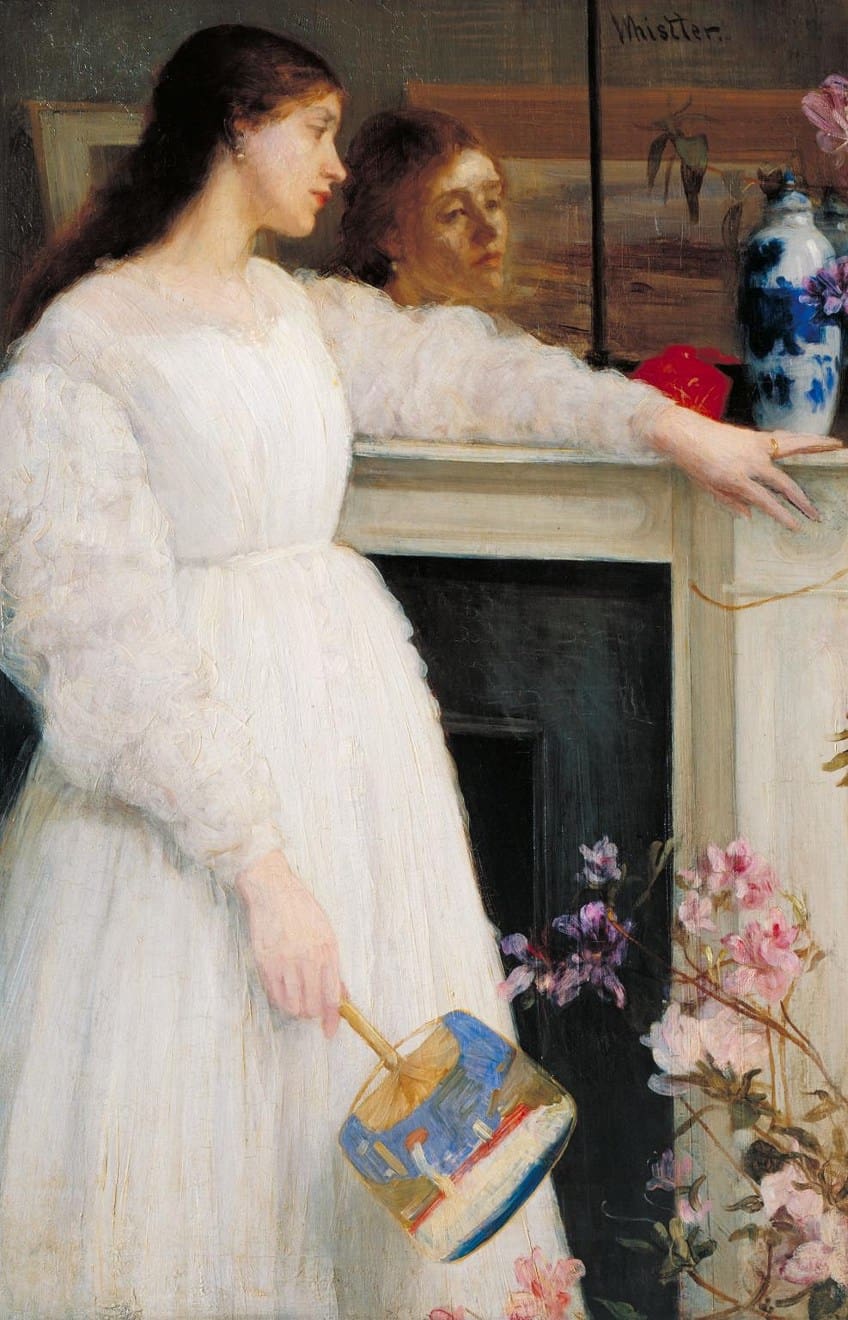

Artists like James Abbott McNeill Whistler began to include these objects in their works, while also altering their compositions to mirror the original style. Christopher Dresser and E.W. Godwin, both designers, were similarly influenced. Within the Aesthetic movement, new aesthetic art styles such as the Anglo-Japanese form gradually evolved.

The Art for Art’s Sake Movement

Aesthetic painters, like their pre-Raphaelite forefathers, put a high value on the visual composition of a piece. However, unlike pre-Raphaelite painting, which nearly always had some narrative component, Aesthetic painters tended to eschew any discernible tale or message.

Instead, they tried to generate a mood, experiment with color harmony, or rediscover the minute details that they identified with high-quality craftsmanship.

Aesthetic painters shouted their slogan, “art for art’s sake,” borrowed from Theophile Gautier’s book, Mademoiselle de Maupin (1836), and drew on a variety of influences, including those of Ancient Greek, Medieval, and Japanese art.

This contemporary concept that art should be judged on its own merits rather than the subject’s importance or accuracy became a rallying cry for artists seeking to distance themselves from Victorian materialism. When Walter Pater argued for the priority of the audience’s aesthetic perception of art, he became one of the most influential advocates of the Aesthetic movement.

Pater claims that “The poetic emotion, the longing for beauty, the real passion for its own sake, contains the most of this wisdom. For art approaches you, offering you nothing but the finest quality of your experiences as they pass, and for the purpose of these moments alone.”

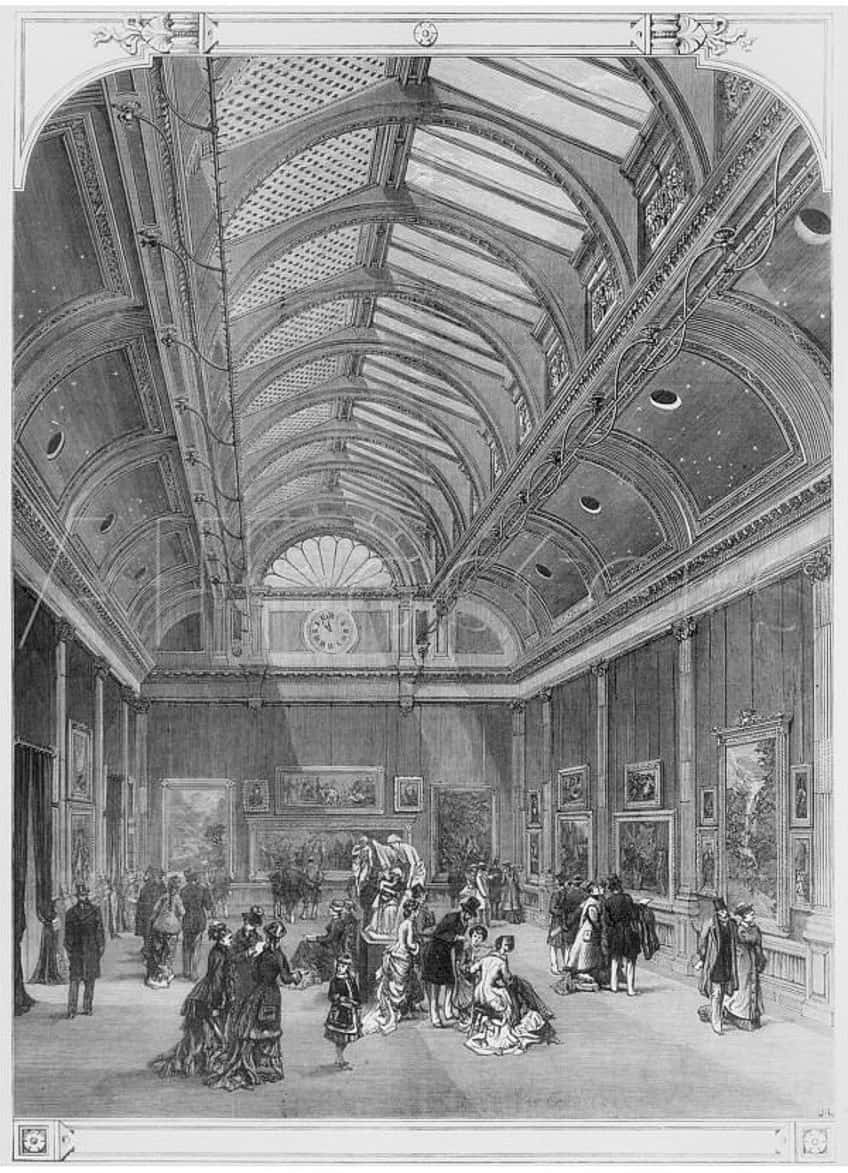

The Grosvenor Gallery

When the Grosvenor Gallery on Bond Street opened in 1877, it gave painters, particularly Aesthetic artists, a place to show work that defied the Royal Academy’s conventional requirements. It boosted the careers of artists such as Albert Moore, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, George Frederic Watts, and Edward Burne-Jones, among others.

The Grosvenor Gallery was not only the first to utilize electric lighting, but it also pioneered a new way of the exhibition (which is now the norm for galleries and museums) in which paintings were placed with adequate spacing to aid the viewer’s immersion.

The exhibition hall was flanked by other sumptuously adorned rooms that followed the Aesthetic design guidelines. It was designed to simulate a painting gallery in a private house. It was derided as the “greenery-gallery” in Gilbert and Sullivan’s comedic opera Patience (1881) because of its iconic green Genoan marble, and yellow-and-green silk damask-coated walls.

Ruskin’s Condemnation

John Ruskin commended the pre-Raphaelites’ artistic expression and believed that design guidelines for machine-produced ornamental arts had deteriorated to the point that they had become monotonous, devoid of spirit and superior craftsmanship. He did, however, argue for art’s societal value, which was in direct opposition to the Aesthetic movement’s philosophy.

Art, according to Ruskin, was more than just a question of taste; it was also a conduit for intelligence, emotion, ethics, and knowledge.

Ruskin issued a harsh evaluation of the paintings when the Grosvenor Gallery debuted in 1877. Ruskin stated, “I have witnessed, and understood, much of cockney impertinence before now; but never imagined a coxcomb to want two hundred guineas for hurling a pot of color in the citizenry’s face” in response to what he believed to be useless material clumsily manufactured. The next year, Whistler brought a libel action against Ruskin, and while the artist’s triumph resulted in a pittance in damages, it was disastrous to Ruskin’s critical reputation, which never made a full recovery.

Ruskin, who had helped numerous pre-Raphaelite artists advance their careers in the 1850s, suddenly found himself out of step with the burgeoning modern art movement.

Aesthetic Art Styles and Concepts

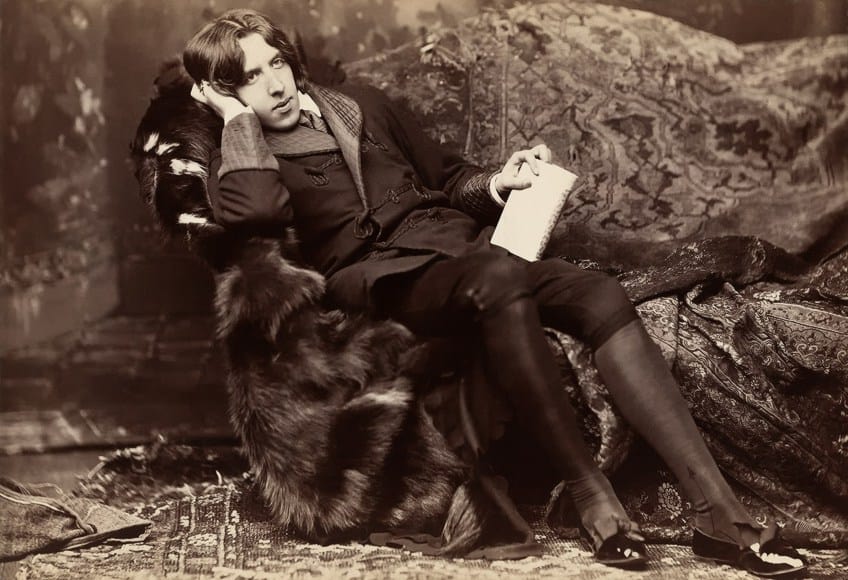

Art, according to the Aesthetic Movement, should not be limited to sculpture, painting, or architecture, but should be commonplace in every sphere of life. Aestheticism encompassed not only the “high” arts, but also pottery, metalwork, clothing, furnishings, and interior design. Many Aesthetes, including Oscar Wilde, took on public identities that allowed them to live by Aesthetic ideals.

Painting

Aestheticism had its initial appearance in artworks, inspired by Rossetti’s sensuous feminine portraits. The ideology and its principles spread to other sectors thanks to this media. Painters were possibly the most qualified of all Aesthetic creatives to accomplish the movement’s purpose of making art for the sake of art.

This is because, unlike the ornamental arts and style, paintings may readily be divorced from their practical uses.

As a result, artists like Whistler, Moore, and Leighton were free to focus only on producing attractive, pleasing-to-the-eye compositions. Aesthetic artists might employ oil paints to experiment with color harmony and tonal variation since the medium allows for subtle tonal alterations. Many of these painters, especially Whistler, included Japanese elements and aesthetics in their works.

Music

There appear to have been no expressly Aesthetic musicians, despite the fact that several Victorian musicians, most notably Eduard Hanslick, advocated formalism and the detachment of music from any need to represent something outside itself. Nevertheless, for many Aesthetic artists, the form was a major source of inspiration. “All the arts aim to the state of music” Walter Pater memorably stated in the 1870s.

Aesthetic painters took this to heart, believing that music created an ideal type of art that paintings might imitate. This method entailed removing narrative information in favor of producing an impression or evocation through color and composition “harmony.”

Painters like Frederick Leighton and James McNeill Whistler even named their works after musical styles. Whistler described how art and music are linked, as well as the artist’s duty as a creator: “The ingredients of all images, in color and shape, are found in nature, just as the notes of all music are found on the piano. But the painter is born to pick, choose, and organize these materials with science so that the end result is beautiful – just as a musician collects notes and makes chords until he creates exquisite harmony out of chaos.”

Architecture

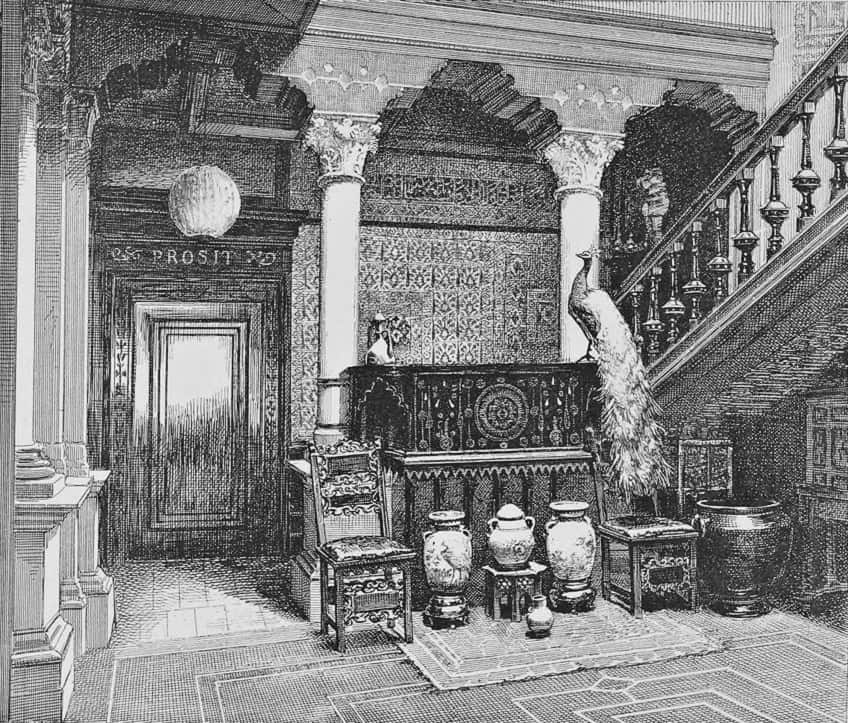

Aesthetes’ studios and residences, which were planned and built under his supervision, strayed from the traditional academic approach by combining seemingly incongruous points of reference to produce an original structural scheme. The house of Frederic Leighton, for instance, included references to the Far East, the Middle East, and the Italian Renaissance.

Guests enter the “Arab Hall,” an artistically adorned domed chamber that integrates many diverse middle-eastern design features, rather than a standard British tearoom.

Concurrently, Whistler created the iconic Peacock Room, which was influenced by a Japanese lacquer box. Industrial artists were frequently called upon to collaborate in these unusual dwellings.

The elegance of the structure as a representation of its multifaceted people outweighed loyalty to any one form for Aesthetic designers.

Design

Designers were acknowledged and even made renowned for their exceptional craftsmanship for the first time during the Aesthetic movement. Designers were seldom acknowledged prior to Aestheticism. However, design as a profession earned respectability as an art form, owing in part to William Morris. Edward Godwin, Christopher Dresser, and William Morris were among the famous designers of the time. Metalwork, fabrics, furniture, and ceramics with geometric forms, stylized floral, vegetable, and zoomorphic themes influenced by the Middle Ages and Japanese aesthetics were developed by these artisans.

These designs were meant to provide an alternative to the fussiness of typical Victorian objects, with clean lines and purity of form.

Some designers, like Morris, started their own labels. Others, like Christopher Dresser and Walter Crane, worked with retailers and manufacturers to make things for the middle class. Aesthetic businesses supplying such things flourished because of Oscar Wilde’s concept of “the house lovely,” which said that a living area interior should be as attractive as possible in order to provide an inspiring atmosphere for its residents.

Arthur Liberty’s Liberty of London, which was established in 1875 and carried fabrics from Japan and the Middle East as well as particularly developed Aesthetic style consumer products, was the most renowned of them.

Fashion

By the 1890s, Aesthetic stores started selling consumer goods to satisfy the public’s desire to dress up as an Aesthete. For some, this meant getting into character. Women abandoned constraining corsets and heavy materials in favor of more “bohemian” free, unstructured garments covered with delicate flower embroidery, emulating the graceful beauty represented in Rossetti’s pre-Raphaelite works. Henna was also used to change the color of certain people’s hair.

Men donned the role of the flamboyant dandy, choosing velvet coats, flowing ties, and trousers, inspired by the gaudy male peacock. The archetypal dandy, playwright, and author Oscar Wilde became the group’s most famous celebrity emblem. Wilde was mocked for his dress taste, as were many other Aesthetic men.

When he attended the inauguration of the Grosvenor Gallery wearing a colorful outfit fashioned to appear like a cello, he drew a lot of flak.

Literature

The beauty of form superseded delivering a social or ethical statement in Aesthetic writing, as it did in the visual arts. Aesthetic poets, most notably Algernon Charles Swinburne and Oscar Wilde, were influenced by Walter Pater’s late-1860s essays to produce sensual poems and prose that were laced with hints rather than unambiguous claims.

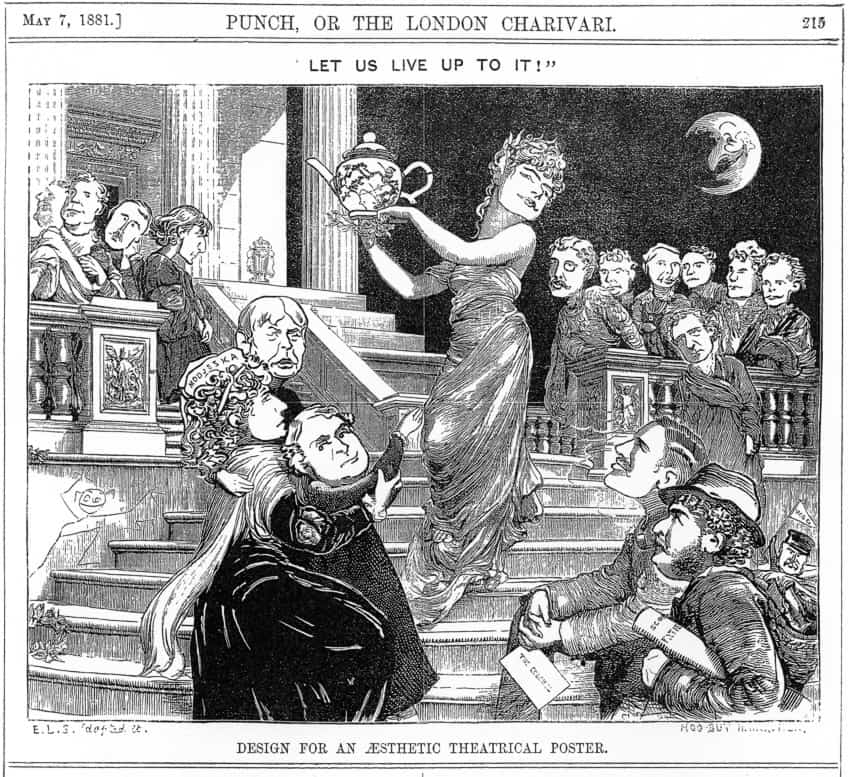

Victorian peers, such as the editors of “Punch” magazine, ridiculed and lampooned aesthetic poetry and authors.

Later Developments

While Aestheticism was popular among many individuals, it was often mocked. Gilbert and Sullivan composed Patience, a humorous opera mocking Aesthetes and their aspirations, in 1881, and George du Maurier created a renowned cartoon depicting a sophisticated “Aesthetic” couple concerned about living up to the precedent of their beautiful teapot.

Because there was no single, unifying idea to link the movement’s participants together, several artists went in separate ways.

For example, socialist William Morris lamented “preaching the gospel to the swinish luxury of the affluent” and worked to make his work accessible to the whole public, not only progressive aristocrats. Morris became a huge advocate of the Arts and Crafts group as his views gained traction.

In the United Kingdom, his engagement prompted designers to resurrect pre-industrial methods in order to separate their work from that of machine-made goods. The Bauhaus movement resolved what Morris could never do in Germany, where disdain for modern machines was not as widespread. They merged craft and design aesthetics with contemporary technology to mass-produce high-quality designs for home products, especially furniture.

Other Aesthetes, such as Aubrey Beardsley and Oscar Wilde, went farther into shaking Victorian civilization out of its lethargy.

Their efforts culminated in the Decadent style, which swiftly lost favor as it became linked with depravity and sexual deviancy, thanks in part to Oscar Wilde’s conviction and incarceration for “lewd conduct” with men. Even though the Aestheticism movement suffered as a result of the popular perception of Wilde’s participation, the contemporary idea of “art for art’s sake” established the movement’s position in art history.

The notion that art has its own inherent worth freed it from the need to have moral or historical significance. For contemporary painters, this repudiation of historical or mythical tales became crucial. It was felt that the artist should have complete autonomy of expression, both in terms of subject matter and artistic portrayal.

The Abstract Expressionist movement of the mid-20th century resulted in this notion of self coupled with a desire to discover the technical side of art and persists to be a foundation of imaginative thinking for many modern artists in the 21st century.

Famous Examples of Aestheticism

Aesthetes, as the movement’s supporters came to be known, increased the artistry and cohesion of many sectors of society. They claimed that life should imitate art instead of the other way around. These reformers introduced forth new concepts that would influence the design world for the following century.

La Ghirlandata (1873) by Dante Gabriel Rossetti

| Date Completed | 1873 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 124 cm x 85 cm |

| Location | Guildhall Art Gallery, London |

La Ghirlandata is often regarded as the “epitome of beauty and love.” Unlike Rossetti’s early pre-Raphaelite works, this image has a softening of line that has been regarded as the artist’s sensuous phase, a form that has more in connection with Aesthetic movement artists.

The composition of the picture is balanced and nearly symmetrical.

A woman carefully strums a harp in the center, her form concealed by billowing drapery and layers of flowering greenery. The delicate characteristics of the woman are mirrored in the faces of two heavenly faces above her.

The color scheme is vivid and harmonious, with the green of her dress blending into the flora, allowing the complementary warm body tones and blazing tresses of hair to stand out.

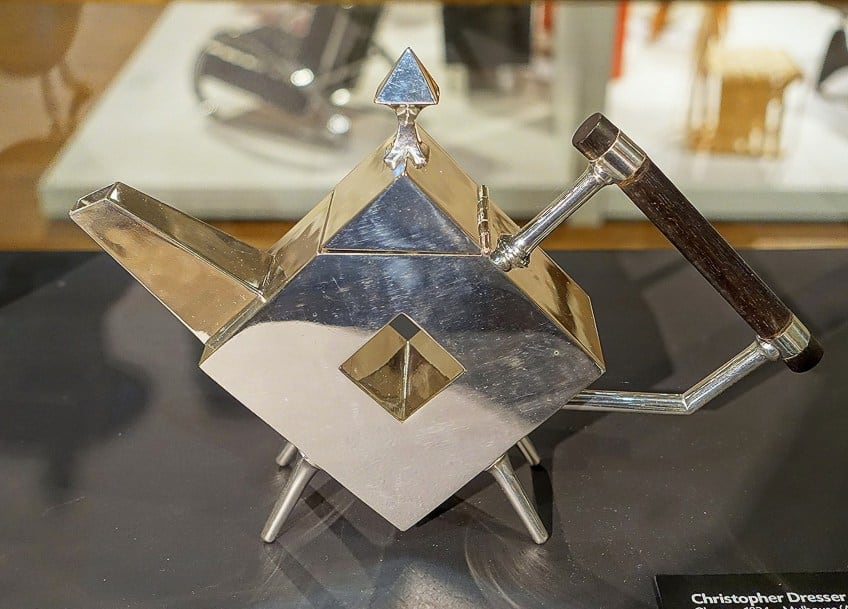

Teapot (c. 1879) by Christopher Dresser

| Date Completed | c. 1879 |

| Medium | Silver and ebony |

| Dimensions | 12 cm x 22 cm x 13 cm |

| Location | Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

This painting’s angular shapes and clean lines contrast with typical Victorian style, which Aesthetes criticized as fussy and convoluted. Dresser was among the first to recognize the need for an industrial design for home products, and that it could be done in a stylish and beautiful way. The artist’s metalwork, in particular, is regarded as a significant predecessor to the Bauhaus’ contemporary designs.

Dresser is described by the Victoria and Albert Museum as “an industrial engineer before the profession was founded, a man who discovered new techniques of creating for manufacturing that few of his colleagues could have envisaged.”

Reading Aloud (1884) by Albert Joseph Moore

| Date Completed | 1884 |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 56 cm x 46 cm |

| Location | Kelvingrove Art Gallery, Glasgow |

Albert Joseph Moore’s paintings usually portray ladies at leisure, dressed in richly draped classical-style gowns. Two ladies lounge on a lavishly covered couch in this painting, listening carefully to another reclining lady reading a book. The ambiance is one of weariness and leisure, with the women set in a semi-exotic setting that adheres to Victorian ideals of safety and decency. The scene lacks dramatic impetus, therefore the flattening, horizontal composition’s effect is mainly ornamental.

Indeed, Moore usually titled his paintings after they were completed, indicating his desire to portray settings that were largely ornamental rather than narrative.

Classical art inspiration for Moore’s picture, however, is not a reproduction of any particular antique source. The artist simply took what he required to create a pleasant image. In this respect, his classicism is obliterated by Aestheticism. Unbothered with historical truth or dramatic story, the artist concentrated on tonal balance and aesthetic impact, as did his acquaintance Whistler.

Moore was very concerned with depicting draperies. The abundance of cloth in this image demonstrates his command of subtle hue, motion, and textural changes. Moore established a name for such classical images, which helped to establish this subject within Aesthetic painting and shed light on the group’s proclivity to take inspiration wherever a painter saw anything visually pleasing.

The Aesthetic movement thrived in England from the 1870s through the 1880s, and it was influential in both practical and artistic arts. Albert Moore, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and some pieces by Frederic, and Lord Leighton are examples of it in paintings. Japanese culture had a significant impact, particularly on Whistler and visual design.

Take a look at our Victorian Aesthetic webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is an Aesthetic Movement?

Aestheticism was a late-19th-century European arts philosophy that held that art existed solely for the pleasure of its attractiveness and that it does not need to have any political, educational, or other function. The movement arose in response to prevalent utilitarian social theories, as well as what was thought to be the harshness and vacuousness of the industrial age. Its intellectual roots of it were established in the 18th century.

What Was the Message Behind Aestheticism?

When the Aesthetic movement asserted that art was free of moral or narrative meaning, it presented a threat to the Victorian public. In an era when art was expected to convey a story, the notion that a simple expression of emotion or something just attractive to gaze at could be regarded as art was a novel one. The Aesthetic movement’s ideals, on the other hand, represent an essential stepping stone on the way to Modern art in their statement that a piece of art may be detached from narrative.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Aesthetic Movement – Art Created for Pure Visual Pleasure.” Art in Context. June 28, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/aesthetic-movement/

Meyer, I. (2022, 28 June). Aesthetic Movement – Art Created for Pure Visual Pleasure. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/aesthetic-movement/

Meyer, Isabella. “Aesthetic Movement – Art Created for Pure Visual Pleasure.” Art in Context, June 28, 2022. https://artincontext.org/aesthetic-movement/.