Jacopo Tintoretto – A Look at the Life Behind Tintoretto’s Artworks

Being in the presence of one of Jacopo Tintoretto’s paintings is to be immersed in a world of chaotic energy, with powerful figures interlaced in rhythms of psychological upheaval and dramatic conflicts. Jacopo Tintoretto’s artworks, which were originally created to decorate the enormous expanses of great halls and sweeping ceilings, loom, daring to burst down the borders between fictitious visual space and the actual world. In Tintoretto’s Last Supper, Saint Mark appears from heaven to defend a vulnerable slave, Christ standing amid his followers, and a tumultuous scene, and even Tintoretto’s self-portraits show the artist’s character rather than merely displaying his skill.

Jacopo Tintoretto’s Biography

Jacopo Tintoretto’s capacity to crumble these physical and emotional obstacles between the spectator and the viewed, as seen in works such as Tintoretto’s Crucifixion (1565) and Miracle of the Slave (1548), put the painter at conflict with the defined etiquette of Renaissance ideology, instantly setting this painter apart from the overwhelming bulk of his colleagues.

Instead, the frenzied brushwork of Tintoretto’s paintings set the groundwork for subsequent generations of painters who would continue on his tradition of creative precision, shifting away from an ideal realism and toward an intensifying feeling of abstraction. We will begin our exploration of the artist by delving into Tintoretto’s biography.

| Nationality | Venetian |

| Date of Birth | c. September 1518 |

| Date of Death | 31 May 1594 |

| Place of Birth | Venice |

Early Years and Education

There seems to be scant information known about Jacopo Tintoretto’s childhood years. Even the actual year of his birth is unknown, with experts putting it between 1518 and 1519. He is believed to have hailed from Venice, rendering him one of the few prominent Venetian School painters to have been born in this region. Giovanni Robusti, his father, was a textile dyer, which influenced his son’s creative approach by immersing the young Jacopo with hues, pigments, and other creative materials almost from infancy.

According to art researcher Stefania Mason, he “gladly acknowledged the family link with dyeing when he acquired the moniker by which he is better known – Tintoretto, ‘the tiny dyer’ – as evidenced in the signing of Tintoretto’s artworks as well as other papers.”

Early Training Period

Although no conclusive records survive, it is widely assumed that Jacopo Tintoretto’s instruction started in his early adolescence with a brief spell as an assistant in the studio of the renowned Venetian artist Titian. This partnership did not survive long, with many assuming that it was due to a major personality clash between the old mentor and the younger student’s more innovative, enthusiastic, and boundary-pushing mentality.

Tintoretto, who was mostly self-taught following this event, would continue to hone his talents, in part by repainting furniture. There was a large market for elaborate chests filled with artwork, in Italy at the period, and it is thought that Tintoretto acquired his particular method during this period, which is distinguished by swiftly completed loose brushwork that frequently appears sketch-like and, at occasions, unfinished.

Tintoretto significantly sums up his approach of form in a number of small-size paintings attributed to his early phase, the sketchy appearance being accentuated by his use of a narrow range of fragmented tones, near to each other on the color spectrum.

These works were designed to embellish furniture and provide credence to Ridolfi’s claim that Tintoretto was friends with artists of this sort, who sold their products from makeshift booths put up in St. Mark’s Square. According to Ridolfi, Tintoretto first learned the “technique of managing colors” unique to the furniture artists in this public setting. Tintoretto’s expressive style, which had originally been associated with the older master Giorgione, was now associated with the lower-ranked Cassoni furniture artists.

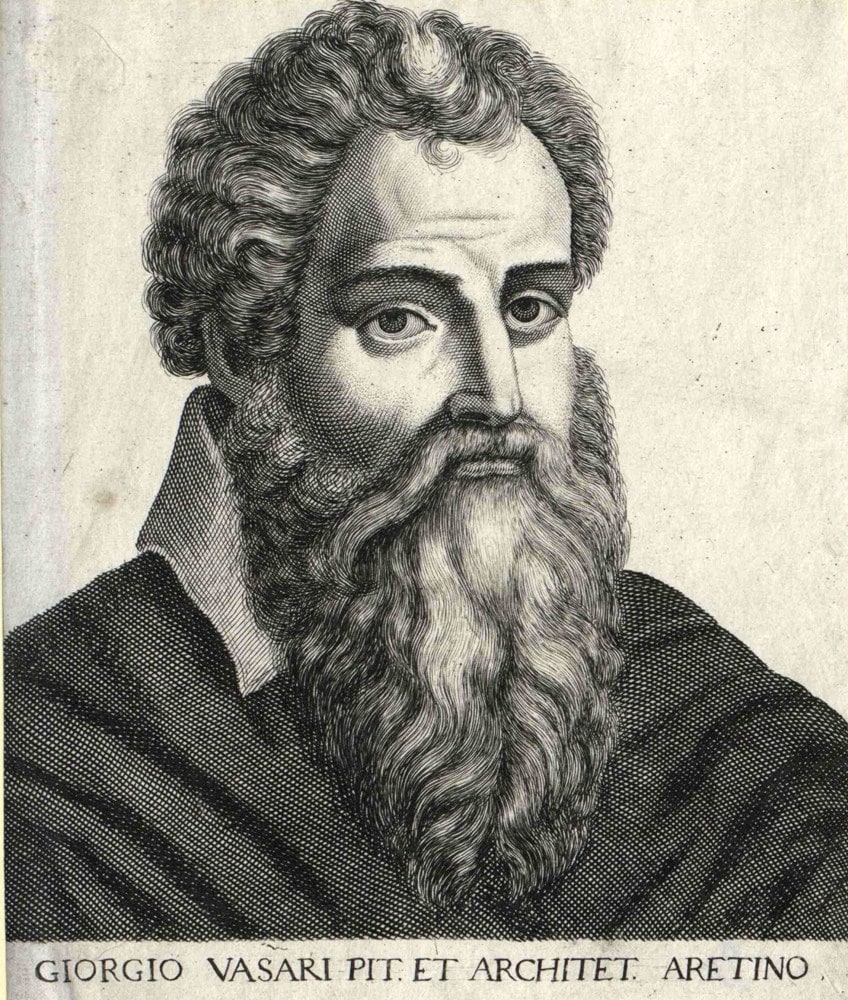

This put Tintoretto at odds with several of his contemporaries and patrons in Venice. The artist Giorgio Vasari’s memoirs, best remembered nowadays for his biographies of Renaissance painters, demonstrate how radical Tintoretto’s style was to his contemporaneous audience.

Vasari says, “This artist has occasionally left us full work ideas that are so crude that the brushstrokes may be seen. Done more by accident and ferocity than by wisdom and intent.”

While this paragraph may appear critical, maybe to demonstrate Vasari’s liking of Titian’s globally renowned and much more refined method, another statement proves Vasari’s appreciation for Tintoretto’s artwork, referencing the youthful painter as “the most exceptional mind that the craft of painting has ever generated.”

Mature Period

There seems to be an indication of Tintoretto establishing his own studio and identifying himself as a professional worker as early as 1538. Notwithstanding the fame of his rival’s work, the young artist distinguished himself from his old instructor Titian from the start. Tintoretto’s fascination in, and mimicry of, Michelangelo’s method of painting irritated his former teacher.

The young artist “put himself in the character of a rebel to the old tradition as personified by Titian and associated himself mostly with the latest concepts flowing in Venetian art,” curator Frederich Ilchman stated in the 2019 show catalog.

In the early 1540s, it meant imitating contemporaneous eddies in Italy, particularly Michelangelo, the most famous name in the Art history of Italy. While the notion of an avant-garde artist striving for “the thrill of the new” had not yet been defined in the 16th century, Tintoretto was establishing himself at the forefront of Venetian art.

However, Titian never pardoned Tintoretto for what he saw as contempt and tried multiple times to stymie the young creator’s career by impeding Tintoretto’s ability to gain contracts and admission in various groups. Despite Titian’s opposition, Tintoretto continued to establish himself, initially via a succession of public projects in the style of fresco paintings.

To obtain access to a bigger audience, he was able to attain employment by charging incredibly cheap prices, frequently simply paying the cost of supplies.

This technique worked, as Tintoretto began to get commissions, including several devotional works for which he would become best known, such as multiple portrayals of Tintoretto’s Last Supper, the first of which he made in 1547. His first masterwork, The Miracle of the Slave (1548), perhaps brought him to the notice of the greater Venetian audience and benefactors, thereby launching his career.

Tintoretto thrived both professionally and personally as his career progressed. He developed acquaintances with several of the day’s top literary leaders. Then, about 1550, he wed Faustina Episcopi, whose father was a member of the congregation Scuola Grande di San Marco, for whom he had produced a piece. They’d have eight offspring, three among whom would go on to become painters. In conjunction with church contracts, confraternities or scuolas were a key source of work for Tintoretto and other Venice artists during the 16th century.

These groups played an important part in the multicultural Venetian society, with goals varying from national origins to deeds of public duty, such as assisting the sick and impoverished.

Over time, these scuolas amassed significant riches from their wealthy members, serving as a key supply of support for Venetian painters. Despite Titian being successful in preventing Tintoretto from completing numerous contracts, including that of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, which Titian had obtained for himself in 1553, he never completed the job. Despite this setback, Tintoretto was able to successfully negotiate the rigorous procedure, which he immensely benefited from throughout his profession.

In fact, despite his remarkable reputation, Tintoretto looked destined to encounter competition from other artists. The second prominent opponent was Paolo Veronese, who arrived in Venice in the late 1550s. Titian informally but openly acknowledged Veronese as his replacement when the senior artist awarded him with a golden chain for completing the greatest ceiling painting for the library of Jacopo Sansovino – a competition from which Tintoretto had been scandalously excluded.

With the desired position of the next ruler of Venetian art slipping between his fingertips, Tintoretto had to cope not just with Titian’s scheming, but also with Veronese’s indisputable brilliance.

Instead of admitting defeat, Tintoretto persisted and reinforced his position by concentrating on works that were distinctive to his manner and distinguished him from Veronese’s and Titian’s more traditional methods. In so doing, he created progressively dramatic compositions, densely crowded with people producing rhythmic extremes in light and shadow that seemed more Mannerist in form than Renaissance.

Tintoretto frequently used unethical techniques to obtain sought commissions, at times lowering the price of his works to undercut other painters. In 1564, the most famous illustration of his strategic cunning was a contest for a ceiling fresco for the main meeting place of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco.

The confraternity’s proposal requested that selected painters, notably Tintoretto, provide a drawing for the projected ceiling fresco.

Rather than presenting a drawing, Tintoretto presented his finished panel, which was already mounted on the ceiling. When others objected, he offered the artwork as a gift, aware that the confraternity was bound to accept gifts. The plan succeeded, and the painter gained an exclusive agreement with multiple assignments over the next 20 years by offering to execute all future works for the home for an annual fee of 100 ducats. Tintoretto was also inducted into the confraternity in 1565, where he held several positions.

Late Period

It is believed that Tintoretto only left Venice once, in 1580, at the age of 62, to visit Mantua. This would occur around four years after the passing of his adversary, Titian, who had dominated the world stage of all Venetian artists. Tintoretto obtained a few notable foreign commissions during this later time, such as a high altar for King Philip II of Spain and several artworks for Holy Roman Emperor Rudolf II. During this time, he also produced an expanding number of non-religious subject works.

In his later years, he also painted portraits and earned several contracts from the Venetian government.

One of his most famous achievements was the large-scale picture Paradiso, which he made for the Ducal Palace in 1592. Tintoretto relied extensively on the assistance of his studio staff to complete his works, including Paradise, as he reached the end of his life. Three of his nine children were famous among his assistants: his sons Marco and Domenico and his daughter Marrieta. Tintoretto perished 15 days after catching a fever.

His children would carry on his studio’s activity for several years, possibly still guided by the phrase Tintoretto had carved on its wall years before: “Michelangelo’s sketching and Titian’s coloring.”

Legacy and Accomplishments

Jacopo Tintoretto made an everlasting imprint on Venetian art in the 16th century and beyond. His distinct approach to artmaking, with quick, free brushstrokes and sharp differences between light and dark, contradicted the established style of Titian, Veronese, and its Venetian colleagues. His daring compositions provided an alternate manner to the standard Renaissance artworks’ hierarchical staging. As a result, Tintoretto is frequently connected with the Mannerism artists of the late Renaissance era. His impact, on the other hand, was felt long after he died.

Tintoretto’s extremely dramatic, even theatrical compositions would inspire the growth of the 17th-century Baroque artistic movement.

The effect of his expressive style, renowned for its evident brushwork marks, reverberates in the impassioned styles of Peter Paul Rubens and Diego Velázquez. Tintoretto’s self-portrait from 1548 is regarded as a predecessor to those of subsequent painters such as Rembrandt, while the introspective tone of his much later self-portrait was praised as “one of the most exquisite works in the world” by modern icon Édouard Manet.

Tintoretto’s impact continues to pervade the realm of painting, most particularly in the big, expressionistic features of his works, which have influenced current painters.

“In our day, such artists as Anselm Kiefer, Emilio Vedova, and Jorge Pombo have expressly evaluated themselves against Tintoretto, creating gigantic paintings loaded with bold brushwork and coloristic techniques,” write Echols and Ilchman.

The Victoria & Albert Museum declared in 2013 that Tintoretto created The Embarkation of St Helena in the Holy Land (1555) rather than his colleague Andrea Schiavone, as originally believed, as part of a set of three paintings illustrating the narrative of St Helena and The Holy Cross. In 2019, the National Gallery of Art, in collaboration with the Gallerie dell’Accademia, prepared a traveling display, the first to the United States, to commemorate Tintoretto’s birth anniversary.

The show includes approximately 50 paintings and over a dozen works on paper by the artist, spanning from majestic portraits of Venetian nobility to holy and mythical narrative themes.

Jacopo Tintoretto’s Art Style

Tintoretto’s intricate compositions stand in sharp juxtaposition to the geometric harmony that was prevalent during the Renaissance period. As a result, the Venetian painter is frequently connected with the Mannerism style, which is distinguished by its departure from the traditions established by Leonardo da Vinci and Raphael.

Tintoretto, on the other hand, is a product of his hometown of Venice, an artistic location famed for its dynamic use of color and light, as well as its vibrant approach to presenting old religious themes, as well as the Mannerist style prominent in Florence and Rome. Tintoretto uses the expressive ability of the human body in his broad compositions so that it is not just the face that transmits the emotional components of the scenario to the viewer, but the complete figure.

Whereas previous Renaissance painters reflected the austerity of Classical Greek art, Tintoretto adopts a highly expressive manner that foreshadows the 17th-century Baroque period.

Tintoretto astonished audiences about 400 years before art critic Robert Hughes’ famous treatise on contemporary art, “The Shock of the New,” with his vastly different technique to creating with speed, agility, and observable evidence of brushwork across the plane of the canvas.

Tintoretto’s expressive brushwork influenced subsequent generations of artists, from the flamboyance of Diego Velázquez’s Classic tenebrism to the mental anguish and lush use of color found in 19th-century Romantic artists such as Theodore Gericault and Eugene Delacroix. Tintoretto’s artwork technique is distinguished by powerful brushwork and the use of long strokes to create curves and highlights. Tintoretto’s paintings stress the energy of moving human figures, and he frequently uses dramatic foreshortening and perspective techniques to heighten the drama.

The motions and dynamics of the figures, rather than facial expressions, communicate narrative information.

There is an agreement in place that shows a plan to complete two historical works of art with 20 individuals, seven of them are portraits – in two months. Sebastiano del Piombo observed that Tintoretto could create as much in two days as he could in two years; Annibale Carracci remarked that Tintoretto was comparable to Titian in several of his paintings, but inferior to Tintoretto in others. Tintoretto’s artistic humor may be seen in compositions like St Louis of Toulouse, St George and the Princess (c. 1552).

He flips the traditional depiction of the topic, in which Saint George slaughters the dragon and saves the princess; here, the diva sat atop the dragon, brandishing a whip. Arthur Danto, an art critic, describes the end outcome as having “as “the royal has taken affairs into her own hands. George extends his arms in a sign of manly weakness, while his lance lies shattered on the ground. It was clearly drawn with an affluent Venetian market in mind.”

A study comparing Tintoretto’s Last Supper (1594) with Leonardo da Vinci’s portrayal of the same subject demonstrates how creative styles changed during the Renaissance. Leonardo’s room is all about classical stillness. In near mathematical perfection, the followers radiate out from Christ.

The same incident becomes spectacular in Tintoretto’s hands when the human characters are accompanied by angels.

A servant is positioned in the center, possibly in allusion to John 13:14–16 in the Gospel of John. Tintoretto appears to be a baroque painter ahead of his time in his frenetic vitality of composition, expressive use of light, and strong perspective effects.

During his career, Tintoretto was considered the most prolific portrait painter in Venice. Although his expertise in painting old persons, such as Alvise Cornaro, has been greatly acclaimed, modern reviewers have frequently dismissed his portraits as formulaic works.

According to art historians, the many portraits from Tintoretto’s workshop that were mostly created by assistants have impeded understanding of his signature portraits, which are muted and solemn in comparison to his narrative works.

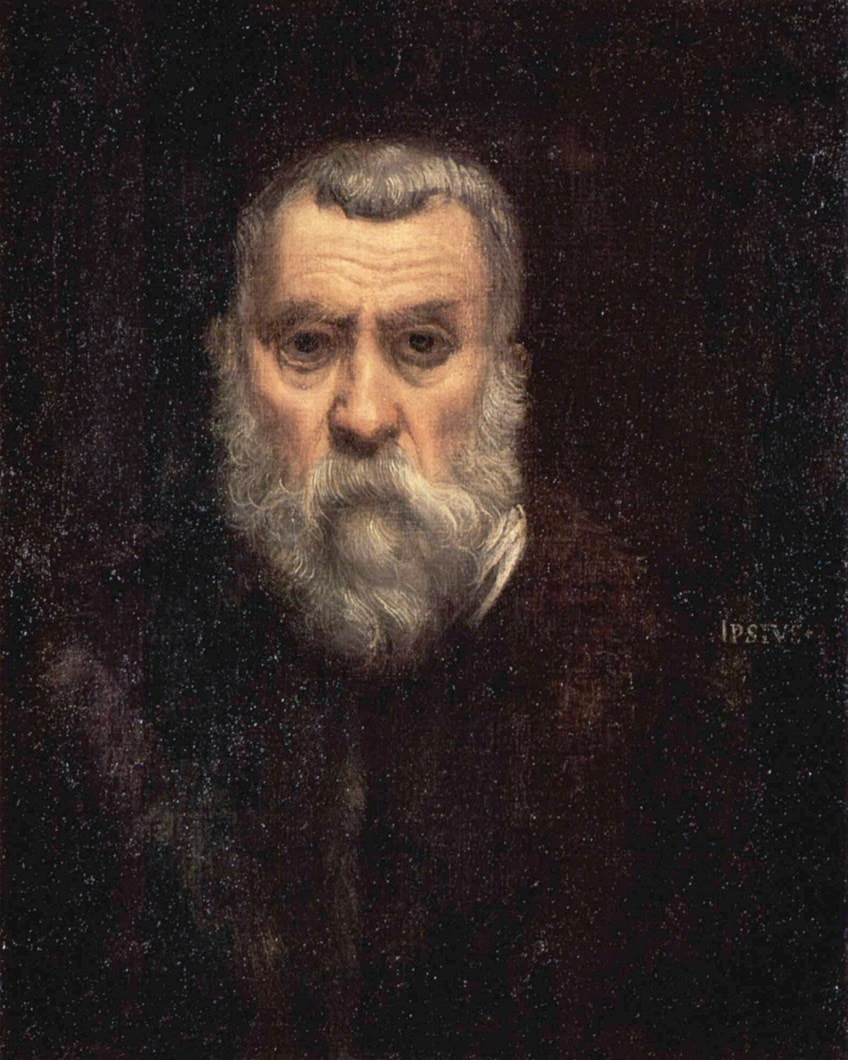

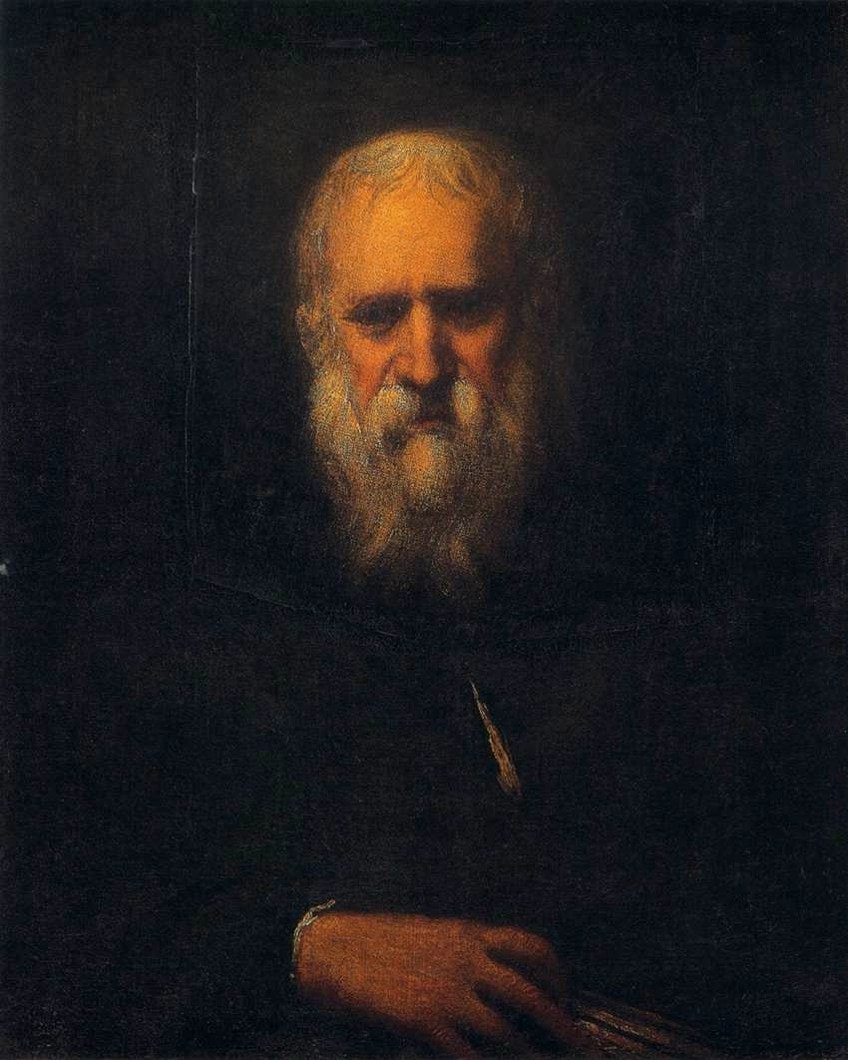

Tintoretto’s “smoldering portrayals of characters who looked devoured by their own fire,” according to Lawrence Gowing, were his “most seductive” paintings. He produced two self-portraits. In the first, he depicts himself without the trimmings of rank that were common in previous self-portraits. The image’s casualness, the subject’s direct glance, and the aggressive brushwork seen throughout were creative and have been dubbed “the first of many beautifully untidy pictures of the self that have passed down through the centuries.”

The second of Tintoretto’s self-portraits is a starkly symmetrical picture of the aging artist “bleakly pondering his death.” It was deemed “one of the most exquisite artworks in the world” by Édouard Manet, who created a replica of it.

Important Examples of Tintoretto’s Artworks

One of Tintoretto’s early paintings, the Presentation of Jesus in the Temple (c. 1550), is preserved in the Carmine cathedral in Venice. For the Scuola della Trinità, he produced four scenes from Genesis. Two of them are the Death of Abel (1552), and Adam and Eve (1550), both splendid works of great skill that show Tintoretto was by this point a skilled artist – among the few who had acquired the highest rank in the lack of any recognized official instruction.

Tintoretto was asked to execute the Miracle of the Slave for the Scuola di S. Marco in 1548. Recognizing that the commission was a once-in-a-lifetime chance to demonstrate himself as a popular artist, he took great care in organizing the contents for maximum impact. The picture depicts the story of a Christian servant who was going to be tormented as a penalty for certain acts of dedication to the evangelist but was spared by the latter’s supernatural intervention, which smashed the bone-breaking and blinded devices that were about to be used.

Tintoretto’s interpretation of the story is noted by its theatricality, distinctive color choices, and energetic execution.

Despite some critics, the artwork was a big success. Pietro Aretino, Tintoretto’s colleague, admired the work, drawing special focus to the image of the slave, but cautioned Tintoretto against fast execution. Tintoretto obtained additional contracts as a consequence of the artwork’s success. He created St Roch in the Hospital (1549) for the church of San Rocco, one of the first of Tintoretto’s numerous horizontal canvases. These were large-scale murals designed for Venetian church sidewalls.

Tintoretto constructed the works with an off-center viewpoint, knowing that the audience would approach them from a slant, so the impression of dimension would be successful when viewed from a position towards the end of the artwork that was nearer to the worshipers. Tintoretto married Faustina de Vescovi, the child of a Venetian aristocrat in 1560. She seems to have been a meticulous homemaker who was able to appease her husband. Faustina gave birth to numerous children for him, three sons and four daughters living to adulthood. Tintoretto had another daughter, Marietta Robusti, before his marriage, the mother of whom is unknown. Tintoretto instructed Marietta and her half-brothers as artists.

Paolo Veronese appeared in Venice in 1551 and soon began earning the prominent assignments that Tintoretto desired.

Unwilling to be eclipsed by his new adversary, Tintoretto contacted the authorities of his neighborhood parish, the Madonna dell’Orto, with the offer of painting two huge canvases for them at no cost. The artist had already finished one of his greatest achievements for the church, the Presentation of the Virgin in the Temple (c. 1553); it rehashes a subject previously depicted by Titian, but instead of Titian’s conventionally proportioned composition is a shocking graphic drama of figures organized on a staircase. Tintoretto now sought to make a commotion by creating the two largest paintings ever produced during the Renaissance period for the Madonna dell’Orto.

He resided in a residence near the building, overlooking the still-standing Fondamenta de Mori. The towering paintings, which depicted the Last Judgment (1559) and the Worship of the Golden Calf (1559), were immensely acclaimed, and Tintoretto established a name for his abilities to finish the most gigantic tasks on a small budget.

Following that, Tintoretto often competed with other artists by creating works rapidly and at a low cost.

Tintoretto’s Crucifixion was painted in 1565 for a fee of 250 ducats. In 1576, he donated another free center-piece, this time for the ceiling of the great hall, depicting the Plague of Serpents; and the next year, he finished this ceiling with images of Moses striking the Rock, and the Paschal Feast, accepting whatever amount the confraternity decided to pay. The invention of quick painting processes enabled him to produce a huge number of works while working on major assignments and to react to increasing customer requests. Tintoretto was able to create more works for the Venetian court than any of his rivals as a result of this, as well as his employment of helpers.

A List of Tintoretto’s Paintings

Tintoretto’s Crucifixion (1565) and Last Supper (1594) are amongst his religious works. However, there are many famous examples of Tintoretto’s paintings. Here is a list of some of his most well-known artworks:

- The Supper at Emmaus (1542)

- Miracle of the Slave (1548)

- Susanna and the Elders (1555-1556)

- The Apotheosis of St Roch (1564)

- The Origin of the Milky Way (1575)

- Christ at the Sea of Galilee (1575)

- The Last Supper (1594)

Recommended Reading

Although we have covered much of Tintoretto’s biography you might be keen to discover more. In that case, you might like to check out some of our books that we can recommend to you. Here is a list of a few great books about Jacopo Tintoretto to have a look at.

Drawing in Tintoretto’s Venice (2018) by John Marciari

Jacopo Tintoretto was a well-known painter of the Italian Renaissance period. Even many art historians are unfamiliar with his drawings, despite the fact that his bold paintings are instantly identifiable. Drawing in Tintoretto’s Venice provides a comprehensive review of Tintoretto’s draftsmanship. It starts with a study at drawings by Tintoretto’s predecessors and contemporaries, with the goal of illuminating Tintoretto’s sources as well as his uniqueness, as well as exploring the historiographical and analytical concerns that have defined every prior discussion of Tintoretto’s graphic work. The following chapters examine Tintoretto’s development as a draftsman and the importance that drawings had in his creative process.

- A complete overview of Tintoretto as a draftsman

- Exploring Tintoretto’s evolution as a draftsman through his drawings

- A vast account of Tintoretto’s drawings and work as a draftsman

Tintoretto in Venice (2019) by Robert Echols

Unlike all the other two famous Renaissance painters connected with Venice, Veronese and Titian, Tintoretto was born in Venice and left a greater imprint on the city than either. His works may still be seen throughout the city, not just in museums, but also as part of the initial artistic sequences in public structures including the Doge’s Palace, Scuola Grande di San Rocco, and the Liberia Marciana, and as religious buildings or chapel embellishments in Venetian churches. Over 120 of Tintoretto’s magnificent paintings pour from the pages, which are split into parts that correlate to the Venetian districts. Each picture is accompanied by an entry produced by an international crew of art historians, who explore significant problems and provide context.

- An exploration of Tintoretto's breathtaking paintings

- Divided into sections according to the Venetian districts

- Each painting is accompanied by professionally-written entries

Being in the presence of one of Jacopo Tintoretto’s artworks is like being immersed in a world of chaotic energy, with powerful figures intertwined in rhythms of psychological turmoil and dramatic confrontations. Jacopo Tintoretto’s paintings, which were originally designed to ornament the vast expanses of immense halls and soaring ceilings, loom, daring to break through the limits between fake visual space and the actual world. Even Tintoretto’s self-portraits demonstrate the artist’s character rather than just his technique.

Take a look at our Tintoretto paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Was Jacopo Tintoretto the Painter?

Jacopo Tintoretto was a Venetian school painter who was perhaps the last outstanding artist of the Renaissance period in Italy. In his childhood, he was also known as Jacopo Robusti, after his father, who had guarded the gates of Padua against imperial forces. He was dubbed Il Furioso for his extraordinary painting intensity, and his spectacular use of conceptual space and unusual lighting established him as a forerunner of Baroque art.

What Was Tintoretto’s Art Style?

Tintoretto’s complex compositions contrast sharply with the geometric harmony that characterized the Renaissance period. As a result, the Venetian painter is commonly associated with the Mannerism style, which is marked by its break from Leonardo and Raphael’s traditions. Tintoretto, on the other hand, is a product of his birthplace of Venice, which is known for its dynamic use of color and light, as well as its energetic approach to portraying traditional religious subjects, as well as the Mannerist style popular in Florence and Rome.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Jacopo Tintoretto – A Look at the Life Behind Tintoretto’s Artworks.” Art in Context. March 7, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/jacopo-tintoretto/

Meyer, I. (2022, 7 March). Jacopo Tintoretto – A Look at the Life Behind Tintoretto’s Artworks. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/jacopo-tintoretto/

Meyer, Isabella. “Jacopo Tintoretto – A Look at the Life Behind Tintoretto’s Artworks.” Art in Context, March 7, 2022. https://artincontext.org/jacopo-tintoretto/.