Diego Velázquez – The Life and Art of Spanish Painter Velázquez

Diego Velázquez the painter was born in Seville on the 6th of June 1599. Spanish painter Velázquez was a prominent painter in King Philip IV’s court as well as the Golden Age in Spain. Velázquez the artist is regarded as an individualistic painter of the Baroque era. Diego Velázquez’s paintings exhibit his detailed tenebrism style, and his later works display a looser style which is defined by bold brushstrokes.

The Life of Diego Velázquez the Artist

Diego Velázquez’s artworks included many depictions of culturally and historically significant scenes, as well as Velázquez’s portraits of the Spanish aristocracy. Paintings by Velázquez became the ideal example for impressionist and realist artists in the 19th century. What is the story behind Diego Velázquez’s paintings, and how did Diego Velázquez the painter become such a world-renowned name? Let us take a look at his life, from the early years and through his periods of development.

The Early Life of Spanish Painter Velázquez

Velázquez was born to Juan and Jerónima Velázquez on the 6th of June 1599. Diogo and Maria Rodrigues, his grandparents, were Portuguese folk who had relocated to Seville decades before. When Velázquez was given a knighthood in 1658, he claimed lineage from the lower aristocracy to qualify; nevertheless, his grandparents were tradesmen, likely Jewish traders. Raised in humble conditions, he showed an early talent for drawing and was assigned to Francisco Pacheco, a Seville-based artist, and instructor.

Antonio Palomino, an early-18th-century historian, said that Velázquez trained briefly under Francisco de Herrera before commencing his tutelage under Pacheco, although this is unconfirmed.

Pacheco, although being regarded as a bland and unremarkable artist, occasionally conveyed a basic, straight naturalism, yet his work remains mostly Mannerist. As a lecturer, he was well-versed in the subject matter and promoted his pupils’ cognitive growth. Velázquez learned the classics at Pacheco’s class, was taught in proportionality and perspectives, and observed developments in Seville’s artistic and literary groups.

Velázquez married Juana Pacheco, the daughter of his tutor, on the 23rd of April, 1618. Velázquez’s early works are known as kitchen still-lifes. He was one of the earliest artists from Spain to portray such settings, and his An Old Woman Frying Eggs (1618) illustrates his exceptional talent in realistic representation.

The naturalism and dynamic illumination of this painting may have been inspired by Caravaggio’s art, which Velázquez might have seen indirectly in reproductions, as well as the polychrome statuary in Sevillian cathedrals.

Two of Diego Velázquez’s artworks, Kitchen Scene with Christ at Emmaus (c. 1618) and Kitchen Scene with Christ in the House of Martha and Mary (1618) have Christian sequences in the backdrops that are depicted in such a way that it is unclear whether the Christian image is an artwork on the wall, a depiction of the kitchen maid’s ideas in the center of the frame, or a real occurrence observed through a window.

The Virgin of the Immaculate Conception (1619) follows Pacheco’s method, except that Velázquez replaces his instructor’s idealistic facial form and flawlessly polished materials with the profile of a local woman and diverse brushstrokes.

Spanish Painter Velázquez’s Early Period in Madrid

By the early 1620s, Velázquez had solidified his status in Seville. In April 1622, he proceeded to Madrid with papers of recommendation to Don Juan de Fonseca, the King’s chaplain. Velázquez was not permitted to portray the new monarch, Philip IV, but instead depicted the writer Luis de Góngora at Pacheco’s insistence.

Góngora was decked with a laurel wreath in the painting, which Velázquez eventually painted over. In January 1623, he went back to Seville and stayed until August.

Rodrigo de Villandrando, the prince’s preferred royal artist, died in December 1622. Velázquez was summoned to the palace by Count-Duke of Olivares, Philip IV’s prominent advisor. He was given 50 ducats to help with his costs, and he was joined by his father-in-law. Fonseca took the young artist into his home and had him sit for a picture, which was then delivered to the imperial court. A picture of the monarch was requested, and the monarch then sat for Philip IV (1623/1628).

The monarch was satisfied with the image, and Olivares ordered Velázquez to relocate to Madrid, vowing that no other artist would ever portray Philip’s image and that all previous paintings of the monarch would be removed from distribution. In the next year, 1624, he got 300 ducats from the monarch to cover the cost of transferring his parents to Madrid, which remained his permanent residence for the rest of his life.

Velázquez was accepted into the royal administration with a monthly income of 20 ducats, accommodation, and remuneration for any paintings he could create. His image of Philip was shown on the stairs of San Felipe and was well appreciated. In 1627, Philip organized a contest for the greatest artists in Spain to depict the departure of the Moors. Velázquez was victorious.

According to documented accounts of his picture (which was lost in a palace inferno in 1734), it represented Philip III gesturing with his stick to a mob of males and females being carried away by troops, while the feminine embodiment of Spain rests in serene repose.

As a result, Velázquez was designated a gentleman herald. Later, he was given a daily stipend of 12 réis, the same as the royal barbershop, plus 90 ducats per annum for attire. Peter Paul Rubens arrived in Madrid in September of 1628 as a messenger from the Infanta Isabella, and Velázquez brought him to the Escorial to see the Titian paintings.

Throughout the seven months of the official expedition, Rubens, who displayed his talent as an artist and nobleman, had positive regard for Velázquez but had no substantial impact on his art. He did, nevertheless, pique Velázquez’s interest in visiting Italy and seeing the masterpieces of the renowned Italian painters.

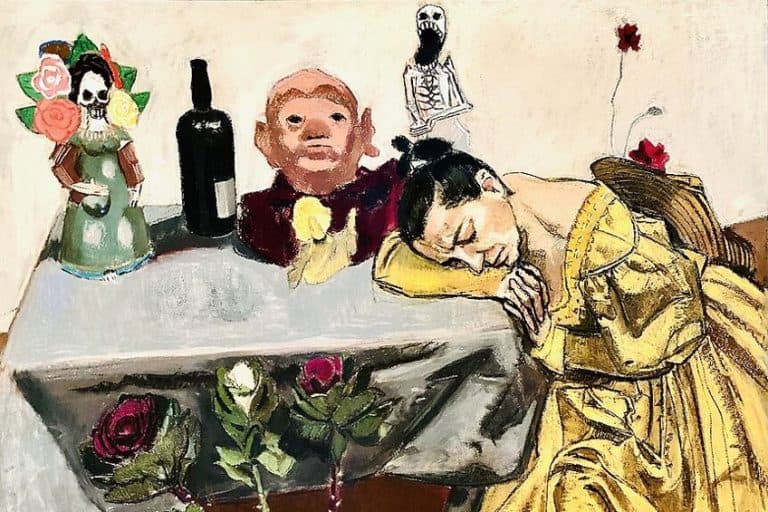

Velázquez got 100 ducats in 1629 for The Triumph of Bacchus (1629), a work showing a group of men dressed in current attire paying tribute to a half-naked youthful man reclining on a wine barrel. It was Velázquez’s very first mythological artwork, and it has been alternately viewed as a picture of a dramatic play, a satire, or a metaphorical image of peasants imploring the god of wine to relieve their miseries.

The manner reflects the realism of Velázquez’s earlier paintings, slightly influenced by Titian and Rubens.

Diego Velázquez the Painter’s Italian Period

Velázquez was granted authorization to stay a year and a half in Italy in 1629. But while this first trip is acknowledged as a pivotal moment in the advancement of his aesthetic – few specifics and details about what the artist viewed, who he encountered, how he had been regarded, and what advancements he wished to incorporate into his artworks are established. He visited Ferrara, Venice, Cento, Rome, Bologna, and Loreto, among other places. In 1630, he traveled to Naples to produce a painting of Maria Anna of Spain, and it is likely that he met Ribera while there.

The significant pieces of his first Italian era are Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan (1630), and Joseph’s Bloody Coat Delivered to Jacob (1630), both of which reflect his intention to compete with the Italians as a magnificent historical artist. The scriptural scene representing deceit and the mythical piece depicting the disclosure of deception have comparable proportions and may have been planned as pendants. Velázquez showed his figures as modern people with ordinary motions and facial reactions, as he had done in The Triumph of Bacchus (1629).

Continuing in the footsteps of Bolognese artists such as Guido Reni, Velázquez created “Apollo in the Forge of Vulcan” on a canvas primed with a pale grey foundation as opposed to the deep red foundation of all his previous pieces.

Velázquez the Artist’s Middle Period

In January 1631, Velázquez traveled back to Madrid. That same year, he finished the first of several of Velázquez’s portraits of the future king. Velázquez represents the royal youth as appearing stately and princely in paintings such as the Equestrian Portrait of Prince Balthasar Charles (1635), or in the uniform of a military leader on his dashing stallion.

In one variation, the scenario takes place in the castle’s riding stables, with the royal couple watching from a terrace, while Olivares serves as the royal’s instructor of the steed.

Velázquez produced equestrian paintings of the ruling household to adorn the emperor’s new castle, the Palacio del Buen Retiro. In Philip IV on Horseback (1635), the monarch is depicted in profile as a picture of unshakeable grandeur, exhibiting skilled horsemanship with smooth ease. Velázquez’s sole remaining artwork showing current events is the massive The Surrender of Breda (1635), also created for the Palacio.

Its metaphorical depiction of a Spanish forces triumph over the Dutch avoids the conquering and supremacy discourse that is common in such situations, in which a commander mounted looks down on his defeated adversary. Rather, Velázquez depicts the Spanish commander as an equivalent before his Dutch adversary, offering a consoling hand to him. The powerful politician Olivares’s stern, dark visage is recognizable to us from Velázquez’s many pictures.

Two are noteworthy: one is full-length, statuesque, and statesmanlike, wherein he dons the cross of the order of Alcantara and clutches a wand-like object, the emblem of his rank as an instructor of the horse; the other, Equestrian Portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares (c. 1636), depicts him attractively as a military leader during activity. Velázquez returned the duty of respect he obliged to the patron who initially drew him to the emperor’s notice with these paintings.

Mars Resting (c. 1638) is both a mythical figure portrayal and portraiture of a tired-looking middle-aged man acting as Mars. The model’s personality is highlighted by his untidy, huge mustache, which is a somewhat funny incongruity.

The ambiguous picture has been viewed in a variety of ways: Javier Ports sees it as an “analysis on realism, expression, and the creative vision,” while Alfonso E. Pérez Sánchez says it “has been perceived as a sorrowful contemplation on Spain’s declining arms.”

Without his royal office, which allowed Velázquez to avoid Inquisition scrutiny, he might not have been permitted to publish La Venus del Espejo (c. 1644). It is the earliest known feminine naked painting by a Spanish painter and the only extant female naked painting by Velázquez.

Velázquez’s Portraits

Apart from the 34 portraits of Philip by Velázquez, he also produced portraits of other royal family members, including, Elisabeth of Bourbon (the King’s first wife), and her children, particularly her eldest son, whom Velázquez had first illustrated when he was about two years old. Velázquez also represented various imbeciles and dwarfs at Philip’s court compassionately and with regard for their uniqueness, as in The Jester Don Diego de Acedo (1644). Velázquez, as a royal artist, received far fewer orders for religious paintings than any of his colleagues. Christ Crucified (1632), produced at the San Plácido Convent in Madrid, represents Christ right after the crucifixion.

The Savior’s face is hung to his chest, and a mess of thick matted hair hides half of his face, graphically accentuating the image of death. The person stands alone against a black backdrop. In 1634, Juan Bautista Martnez del Mazo, Velázquez’s son-in-law succeeded him as herald, and Mazo likewise had steadily advanced in the royal family. Mazo was named director of projects at the castle in 1647 and got a stipend of 500 ducats in 1640, which was extended in 1648, for portraiture completed and yet to be done. Philip now tasked Velázquez with acquiring artworks and sculptures for the imperial museum.

Spain was rich in images but lacking in statues, so Velázquez was sent back to Italy to negotiate acquisitions.

Velázquez the Artist’s Next Italian Visit

When he left in 1649, he was escorted by his helper Juan de Pareja, who was a servant at the time and had been taught painting by Velázquez. Velázquez traveled from Málaga, arrived in Genoa, and traveled from Milan to Venice, purchasing Titian, and Veronese works along the way. At Modena, he was warmly welcomed by the royals, and it was here that he produced the duke’s picture, as well as a couple of portraits that now hang in the Dresden exhibition, as these works were purchased at the Modena auction in 1746. Those paintings foreshadow the arrival of the artist’s third and most recent style, exemplified by the famous painting Portrait of Pope Innocent X (1650), where Velázquez currently worked.

The Pope welcomed him with open arms and awarded him with a plaque and a gold necklace. Velázquez brought a duplicate of the picture, which Sir Joshua Reynolds considered to be the best in Rome, along with him to Spain. There are several replicas of it in various collections, some of which may be sketches for the real or reproductions produced for Philip. Velázquez had now attained the manera abreviada, a name created by modern Spaniards for this stronger, crisper aesthetic, with this piece.

The painting depicts the pope with such harshness in his face that some in the Vatican believed it would be viewed negatively by the Pope; nonetheless, Innocent was delighted with the piece and put it in his formal guest’s reception area.

In Rome, Velázquez also produced a painting of Juan de Pareja (1650). This image earned him admission to the Accademia di San Luca. According to legend, Velázquez painted this picture as a practice run for his painting of the Pontiff. With sparse brushstrokes, it portrays Pareja’s expression and his rather tattered and tattered attire in remarkable clarity. Velázquez set Juan de Pareja loose in November 1650. Also from this time period are two tiny landscape works named View of the Garden of the Villa Medici (1629).

They were unique for their period as landscapes that appeared to be created straight from reality, and they reflect Velázquez’s meticulous observation of light at various times of the day. Velázquez ordered Matteo Bonuccelli to produce 12 bronze reproductions of the Medici beasts as a portion of his effort to get ornaments for the Room of Mirrors at the Royal Alcazar of Madrid. Velázquez sired a biological son, Antonio, during his tenure in Rome, although he is not believed to have seen him.

Later Paintings by Velázquez

Philip IV continually requested Velázquez’s return to Spain beginning in February 1650. As a result, after touring Venice and Naples, where he encountered his dear acquaintance Jose Ribera, Velázquez went to Spain through Barcelona in 1651, bringing with him several portraits and 300 items of sculpture, which were later collected and documented for the monarch.

The monarch wedded Mariana of Austria, which Velázquez subsequently depicted in a variety of poses after Elisabeth of France passed in 1644.

In 1652, he was expressly selected by the monarch to assume the prestigious post of royal mayor, which entrusted him with the responsibility of overseeing the lodgings inhabited by the royals – a significant role that was no cushy job and conflicted with the practice of his craft. Despite this, his paintings from this time frame are among the best representations of his aesthetic.

The Creation of Las Meninas (1656)

Margaret Theresa, the incoming queen’s eldest child, seems to be the focus of Velázquez’s greatest effort. Las Meninas was completed four years before the artist’s demise and is regarded as a masterpiece of Baroque art in Europe. Modern Italian artist Luca Giordano alluded to it as “doctrine of art,” while Thomas Lawrence described it as a “philosophical tradition of painting” in the 17th century.

Nevertheless, it is unknown who or what the genuine focus of the image is. Is it the regal child, or the artist himself? The royal couple is mirrored in a glass on the rear wall, but the origin of the projection is unknown: are the royal couple sitting in the audience’s space, or is the mirror reflecting the work on which Velázquez is making progress?

According to Dale Brown, Velázquez may have seen the fading picture of the monarch and queen on the rear wall as a portent of the Spanish Empire’s impending dissolution following Philip’s demise.

The Final Years of Velázquez the Artist

In Spain, there were basically two supporters of art: the clergy and the art-loving monarch and palace. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, who worked for a wealthy and influential monastery, left little money for his funeral, whereas Velázquez lived and died with a solid income and annuity. Las Hilanderas (1657), was one of his last masterpieces.

The fabric in the backdrop is based on Titian’s work, or, more likely, a duplicate produced by Rubens in Madrid.

The last of Velázquez’s final portraits of the heirs to the throne are among his greatest accomplishments, and in the Infanta Margarita Teresa in a Blue Dress (1659), the artist’s sense of style achieved its peak: glistening patches of coloring on wide painting areas generate a nearly impressionistic feeling – the audience must stand at an appropriate distance to get the perception of comprehensive, three-dimensional spatial configuration.

His sole surviving image of the frail and ill Prince Felipe Prospero is notable for combining the little prince’s and his dog’s lovely characteristics with a slight air of sadness. The representation reflects the optimism that was put at the time in the single heir to the Spanish throne: new white and red contrast with late fall, somber tones. A small puppy with big eyes asks the spectator a question, and the generally pale background suggests a bleak fate: the young prince passed away when he was just four years old.

The treatment of the colors is incredibly flowing and brilliant, as it is in all of the creator’s most recent works.

The wedding of Maria Theresa and Louis XIV in 1660 sealed a peace pact between Spain and France, and the event occurred on a little marshy island in the Bidassoa. Velázquez was tasked with decorating the Spanish pavilion as well as overseeing the whole scenic show. The grandeur of his attitude and the splendor of his outfit drew a lot of attention to him. He traveled to Madrid on June 26 and became ill with a fever on July 31. As his death approached, he wrote his testament, naming his wife and a strong friend called Fuensalida, custodian of the royal archives, as his only executors. On the 6th of August, 1660, he passed.

The Legacy of Diego Velázquez’s Artworks

Velázquez was not a productive painter; it is thought that he created between 110 and 120 known works. He didn’t make any etchings or prints, and just a few sketches are ascribed to him. Velázquez is the most significant person in Spanish portrait tradition. Although he had few direct successors, his work inspired Spanish royal artists such as Juan Bautista Martinez del Mazo. Mazo closely imitated his manner, and many of his works and replicas were previously assigned to Velázquez.

In the 17th century, when Spanish royal painting was controlled by painters of foreign blood and education, Velázquez’s prestige suffered.

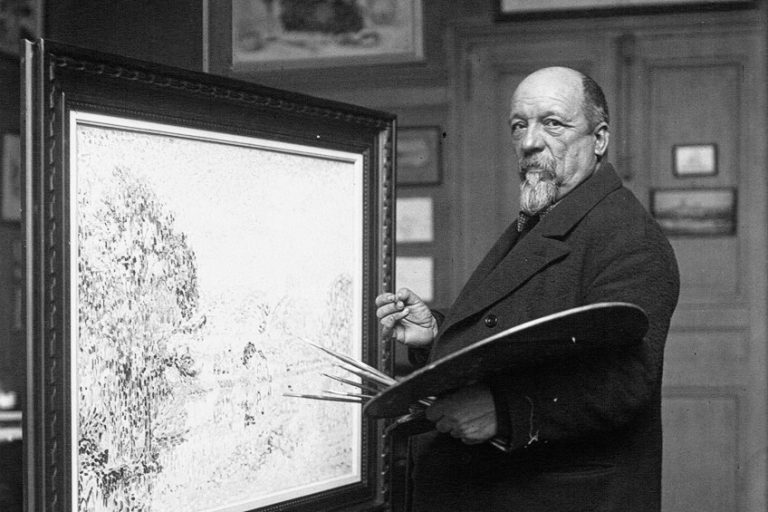

Towards that turn of the era, scholars close to the King of Spain began to acknowledge Velázquez’s importance – in an article published by Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos in 1781, he remarked of Velázquez, “when he died, the grandeur of Art in Spain perished with him.” In 1778, Goya created a series of etchings based on paintings by Velázquez as a portion of the Count of Floridablanca’s attempt to manufacture copies of artworks in the Imperial Collections. Goya’s free reproductions indicate a probing involvement with the technique of the elder master, which served as a model for Goya for the remainder of his work.

Diego Velázquez’s Paintings Technique and Style

It is customary to split Velázquez’s career into two halves based on his two travels to Italy. He seldom signed his paintings, and only his most notable pieces are dated in the royal records. To some extent, the remainder is supplied by internal documentation and background connected to his portraits.

Despite being familiar with all of the Italian traditions and a companion of the most prominent artists of his time, Velázquez was able to resist external factors and figure out for himself the formation of his own character and ideas of painting.

He is noted for employing a limited palette, but he combined the existing paints with amazing expertise to obtain a variety of hues. His pigments were similar to those of his colleagues, and he mostly used, smalt, azurite, vermilion, lead-tin-yellow, ochres, and red lake. His early paintings were created on canvases that had been primed with a red-brown basis.

During his first journey to Italy, he embraced the usage of light-gray grounds, which he proceeded to utilize for the remainder of his life. The transformation resulted in artworks with increased brilliance and a usually cold, silvery color palette. Few sketches may be confidently credited to Velázquez.

Although some of his works had preparation sketches, his style was to create straight from reality, and X-rays of his works show that he regularly changed his arrangement as the paintings advanced.

A List of Famous Paintings by Velázquez

- Old Woman Frying Eggs (1618)

- The Supper at Emmaus (1623)

- The Triumph at Bacchus (1629)

- The Surrender of Breda (1635)

- Portrait of Innocent X (1650)

Further Reading

Diego Velázquez the artist lived a very interesting life. Perhaps you have been encouraged to learn more about the Spanish painter Velázquez. If so, we have put together a list of potential books for you to buy and explore.

Rembrandt and Velázquez: Dutch and Spanish Masters (2020)

This anthology showcases the finest work of two 17th-century renowned artists from Spain and the Netherlands, matching works by each while also considering their colleagues and countrymen such as Zurbarán, Hals, Valdés Leal, Ribera, and many others. Each pairing tells a tale or highlights a topic that connects the two works, ranging from religion, faith, riches, or love notions to creative obstacles like balance, lighting, and shading.

They were two of the most important artists in their individual nations. Both painters operated in an environment that featured many other well-known artists While there was no actual interaction between the artists from the Northern and Southern regions, they have striking parallels, not only in creative ambition but also in the desire for realism and their depiction of religious topics.

Diego Rodríguez De Silva Y Velázquez (Art for Children) (1988) by Ernest Lloyd Raboff

A short history of the 17th-century Spanish artist is included, as well as fifteen colored copies and scholarly analyses of his paintings. This book is brimming with beautiful pictures. It would be an excellent introduction to the artist for younger children.

- A brief biography of the 17th-century Spanish painter Velázquez

- With 15 color reproductions and critical interpretations of his works

- Teaches young students how to examine a piece of art

And with that, we wrap up our look at the life of Diego Velázquez the artist. Paintings by Velázquez became the ideal example for impressionist and realist artists in the 19th century. Diego Velázquez the painter is regarded as being responsible for bridging impressionism and realism. Diego Velázquez’s artworks included many depictions of culturally and historically significant scenes, as well as Velázquez’s portraits of the Spanish aristocracy. His artwork left a lasting impact and legacy on many artists that followed.

Take a look at our Diego Velázquez paintings webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is Diego Velázquez Famous For?

He is most known for pushing the boundaries of portraits and landscape painting. His distinctive naturalistic approach, a predecessor to realism, prioritized authenticity above romanticism and distinguished him from others of his period who stuck to conventional and historical methods of presenting their topics. He succeeded to construct a fiercely independent and outstanding collection of works that underscored his fundamental enthusiasm for the human experience.

What Are Spanish Painter Velázquez’s Accomplishments?

Despite being hired to make art for the aristocracy, Velázquez retained a strong devotion to depicting regular people and settings. He was able to overcome the outside forces of public perception, which saw this effort as useless or worthless, by making pieces that were so captivating that they could not be ignored. Velázquez’s realistic, highly direct technique of portraying truth was far ahead of its time. He employed a variety of approaches to correctly express detail and its numerous intricacies, including free, loose brushstrokes, gradients of light, color, and shape, and attention to details that were unrivaled by his colleagues.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Diego Velázquez – The Life and Art of Spanish Painter Velázquez.” Art in Context. November 23, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/diego-velazquez/

Meyer, I. (2021, 23 November). Diego Velázquez – The Life and Art of Spanish Painter Velázquez. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/diego-velazquez/

Meyer, Isabella. “Diego Velázquez – The Life and Art of Spanish Painter Velázquez.” Art in Context, November 23, 2021. https://artincontext.org/diego-velazquez/.