Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art

Considered the cradle of Civilization, ancient Mesopotamia was home to Sumer, located in the southern parts and one of its earliest and advanced civilizations during the Neolithic and early Bronze age. This article will explore the Sumerian culture and their artwork, ranging from pottery, statues, and architecture.

Brief Historical Overview: “The Land Between the Rivers”

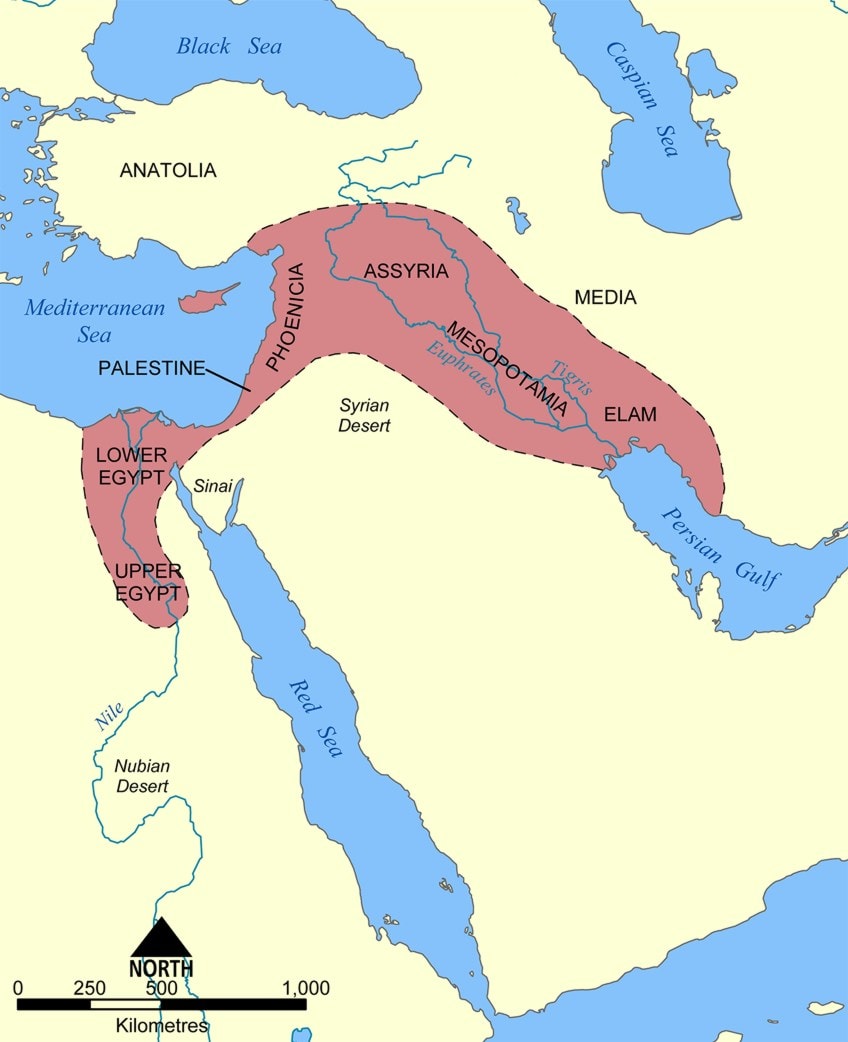

The Fertile Crescent can be found in the Near Middle East. It is also considered a Cradle of Civilization because of the rate of evolution of farming settlements, domestication, and other technological and cultural advancements like the wheel and writing. The name was introduced as the “Fertile Crescent” by the archaeologist James Henry Breasted in the publications Outlines of History (1914) and Ancient Times, A History of the Early World (1916). He described this region of the Middle East as follows:

“This fertile crescent is approximately a semi-circle, with the open side toward the south, having the west end at the southeast corner of the Mediterranean, the center directly north of Arabia, and the east end at the north end of the Persian Gulf”.

Other sources describe it as a “boomerang” shape, with the various regions surrounding it. These regions include areas of present-day Cyprus, Egypt, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, Syria, and Turkey.

As the name suggests, it was a fertile region with arable land and fresh water sources. Its vast biodiversity made it fit for farming and agriculture thousands of years ago when hunter-gatherers gradually transitioned to a more settled way of life. It is also located between North Africa and Eurasia and has been described as a “bridge” between these two regions.

It is no wonder then that the Fertile Crescent has been regarded as a Cradle of Civilization – it has been the birthplace of development and advancements of not only human civilization but also biodiversity.

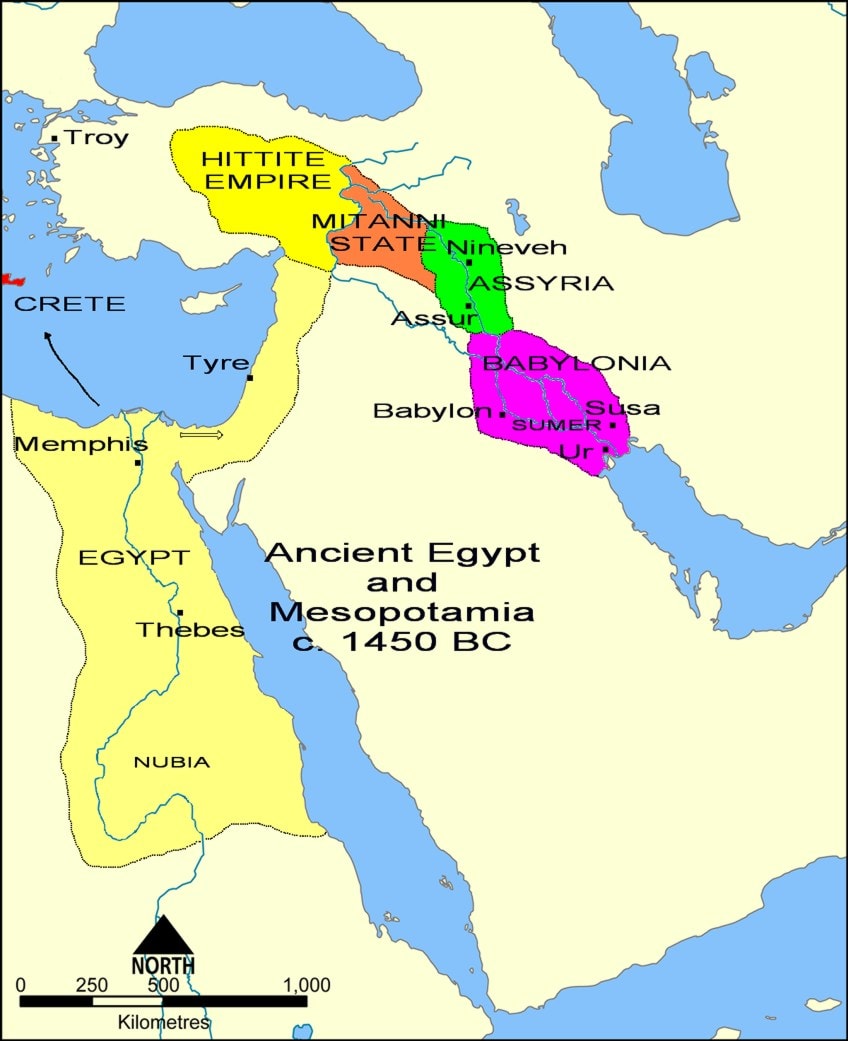

If we zoom in to some of the first human civilizations that started here, we will find ancient Mesopotamia, which is now in the region of present-day Iraq, and other regions like Iran, Syria, Turkey, and Kuwait. Mesopotamia lies between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers and the name means the “land between the rivers”. It is one of four other river valley civilizations, the others being the Indus Valley Civilization, the Nile Valley in ancient Egypt, the Yellow River in ancient China.

Some historical scholars also suggest that the Agricultural, otherwise Neolithic, Revolution originated in ancient Mesopotamia. The dates suggested it started around 10 000 BC. Some of the earliest farming settlements or villages discovered date to around 11 500 BC to 7 000 BC. The archaeological site Tell Abu Hureyra is one example of this.

The people from Abu Hureyra are believed to have been hunter-gatherers who progressed to farming. Grinding tools were also excavated from this area, which suggests the inhabitants had access to grains, possibly the harvest of wild grains as it has been suggested.

It has also been discovered that early inhabitants domesticated animals like pigs and sheep also around the time of 11 000 to 9 000 BC, and farmed plants such as barley, flax, lentils, and wheat, dating to around 9 500 BC.

The Mesopotamian cultures were considered advanced in their developments – they created aqueducts, irrigation systems, astronomy, philosophy, the earliest forms of writing, and much more. It was one of the most complex regions in the world because of the diversity of cultures that moved through it.

Some of the important civilizations from ancient Mesopotamia include Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians, and Babylonians. While there were many city-states throughout Mesopotamia, some of the important cities included the Sumerian Uruk, Ur, and Nippur. There was also Akkad, which was the capital city of the Akkadian Empire, the Assyrian cities Nineveh and Assur, and Babylon, the capital city of the Babylonian Empire.

Earliest Ancient Civilizations: Sumer

Sumer was one of the earliest Mesopotamian civilizations, which originated before the Akkadians, mentioned above. Sumer is in the southern part of Mesopotamia and is believed to have been settled around 4 500 BC to 4 000 BC.

The name “Sumer” was given to the Sumerians by the Akkadians, ironically.

“Black-headed people” or “Black-headed ones” is what the Sumerians used as their name for themselves. The Akkadians also used this terminology for the Sumerians. The word Kengir, meaning “Country of the Noble Lords” was the name the Sumerians used for their land.

There is a lot of scholarly debate about who the first people were to settle in Sumer; some suggest West Asian and others North African. It is generally believed that the first populations or settlements in Sumer were the Ubaidians or “proto-Euphrateans”.

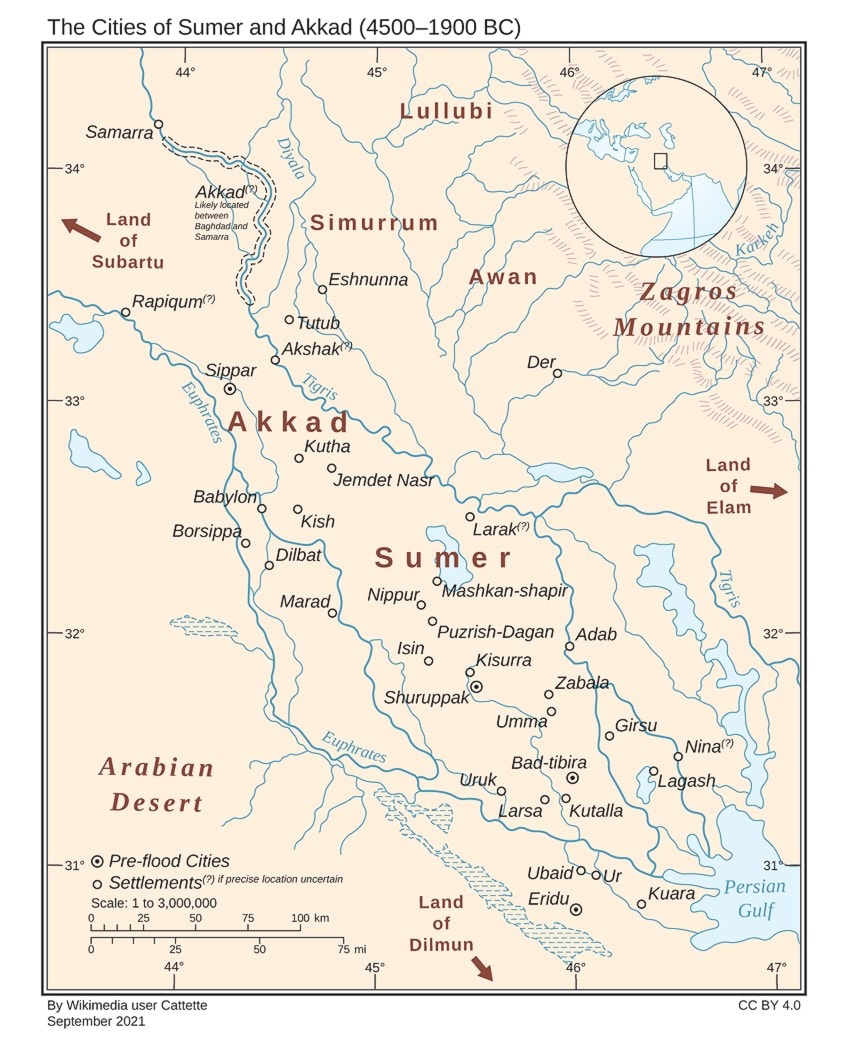

According to various sources, the Ubaidians started agriculture by draining the surrounding marshes, they also developed trading systems and various crafts like weaving, metalwork, leatherwork, pottery, and masonry. The first and oldest settlement was believed to be Eridu, located southwest of the city called Ur.

Eridu was reportedly among five of the cities that were ruled by either a king or a “priestly governor” before floods were destroyed. The settlements were built around respective temples that venerated a patron god or goddess.

The Sumerian god, Enki, was also believed to have originated from Eridu at a place called Abzu, the waters or ocean, otherwise aquifers, under the earth; he was the god of water. Enki’s temple, otherwise referred to as the “House of the Aquifer”, was in the center of Eridu. The other pre-flood Sumerian cities include Bad-tibira, Larak, Sippar, and Shuruppak.

The Importance of Uruk

Uruk was considered one of the first “real” city-states when Sumerian civilization became more urbanized. It started around 4 000 BC and lasted until around 3 200 BC. There were various state formations like societal stratifications, military, and administration systems. It was divided into the Early Uruk Period (c. 4 000 BC to 3 500 BC) and the Late Uruk Period (3 500 BC to 3 100 BC).

It was one of the largest city-states in southern Mesopotamia with around 40,000 inhabitants and an estimation of around 80,000 to 90,000 people in the surrounding areas. It is believed to have reached its peak around 2 800 BC.

The Sumerian King List reportedly indicates that Uruk had five dynasties. It is worth noting that the fifth ruler (of the first dynasty) was the famous Gilgamesh who ruled around 2 900 BC to 2 700 BC. He was also the subject of the epic poem called the Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 2 100 BC to 1 200 BC).

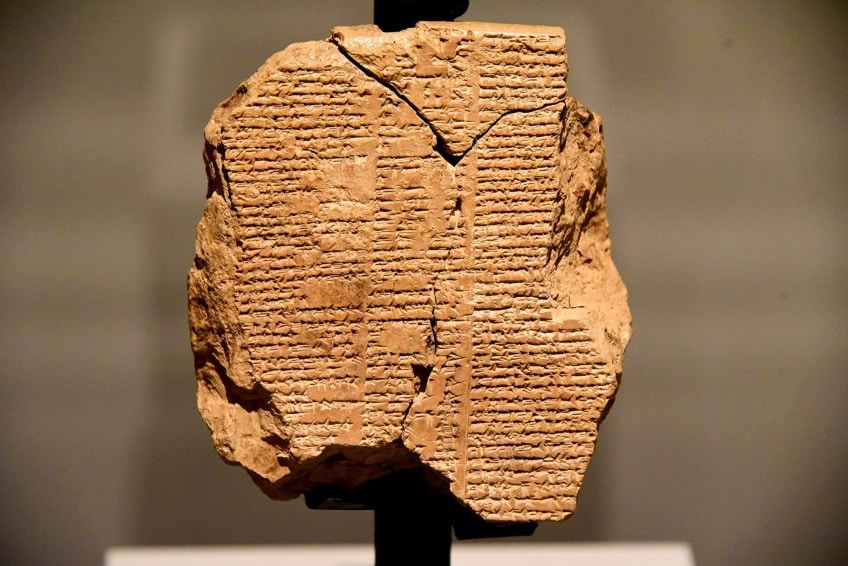

Uruk is an important Sumerian city to note because of its advancements in urbanization as we will see from the wide range of the Sumerians’ architecture. Included were cultural advancements like writing, which is now known as the cuneiform script. It was initially used to record business transactions. These transactions were for purposes of keeping records of food and cattle. It was used by the ruling priests of the area.

The cuneiform script was made by pressing down a cut edge from a reed onto a clay tablet that was still soft. This created a shape that appeared like a wedge. The name also originates from the Latin meaning “wedge-shaped”.

This written language became a very flexible one because it could convey not only words but also numbers and concepts.

Sumerian Art

The Sumerian civilization was not only advanced in agriculture, economics, and many other facets of life, but they were also artists and builders. Their artworks served different purposes and functions and the addition of decorative elements gave any object a new character.

We will see this in the numerous Sumerian statues throughout the different dynasties. For example, the Standing Male Worshipper (c. 2 900 BC to 2 600 BC), now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, depicting a man standing with both his hands cupped in front of his breastbone with a lustrous long beard and open eyes gazing outward; his facial features have been sculpted in an animated manner.

Not only were the Sumerians skilled at pottery and sculpture, but they produced beautiful pieces with these decorative elements made from semi-precious stones like alabaster, lapis lazuli, and serpentine to name a few. Some of these stones were also imported. They used metals like silver, gold, bronze, and copper as inlays and designs on various objects.

The Sumerians also used stone and clay. Clay was a popular medium to work with, possibly due to the clay present from the soil, and we will see a lot of Sumer art made from it. Decorative elements would adorn various items like jewelry, carved heads, musical instruments, ornamentation, weapons, cylinder seals, and many others.

The majority of Sumer art originates from gravesites; indeed, many objects, often important objects, were buried with the dead.

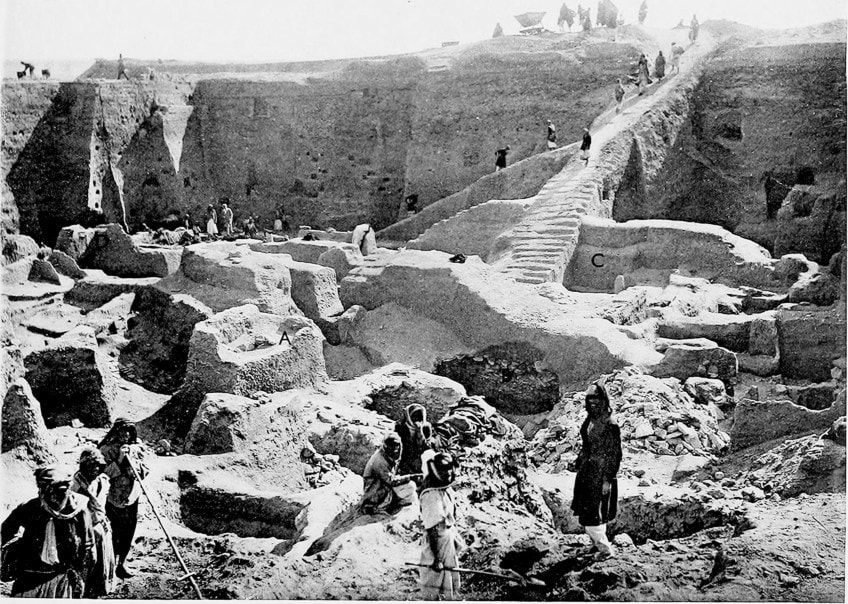

This also tells us that art served strong religious purposes during this period. One of the most important archaeological discoveries in history has been that of Sir Leonard Woolley, his wife Katharine Woolley, and their collaboration with the British Museum and the Museum of University of Pennsylvania.

From 1922 to 1934, Woolley, who was a British archaeologist, led an excavation at one of the Sumerian cities called Ur. The layout of the city consisted of central mud-brick temples with a surrounding cemetery. This is also where they discovered the Royal Cemetery, which was reportedly in an area used as a large rubbish heap where people could not build.

Instead, it was utilized as a burial site with various tombs that are believed to have belonged to Sumerian royalties.

The cemetery was dated from around 2 600 BC to 2 000 BC and the discovery of 16 graves dates these to around the middle of 3 000 BC. The tombs were also different in arrangement and size. The excavation team reportedly found over 2000 burials.

The tombs housed a plethora of objects like pottery including bowls, jars, and vases, jewelry, cylinder seals with inscriptions of the names of those who were dead, musical instruments of which lyres were quite prominent, sculptures, Sumer paintings, and many others.

One of the famous burial sites belonged to a woman, believed to be a “queen”, called Puabi.

She lived in the First Dynasty of Ur, around 2 600 BC. She was referred to as nin from the discovered cylinder seals. Nin is a Sumerian word that was used to refer to someone who was designated as a queen or priestess. It has also been translated to mean “lady”.

Her burial grave included numerous items that were tied to wealth, these were also high in quality items like jewelry, headdresses, including her own headdress with gold floral motifs and beads made from lapis lazuli and carnelian.

Sources also state these gravesites were looted over the years except for Puabi’s grave, which undoubtedly elicited questions about her status and importance in the Sumerian society.

It is important to remember there are hundreds of discovered Sumerian artifacts, all from different regions and all with different purposes and stories. Below we will discuss only a few of the famous pieces of Sumerian art, including, but not limited to some of the items discovered from the Royal Graves, including that of Puabi’s grave. It is encouraged to undertake more extensive research to discover all the other unique and beautiful Sumerian art pieces that adorn our museums in the present day.

Ram in a Thicket (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC)

The Ram in a Thicket (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC) is a figurine of a ram, really a goat, standing on its hind legs in front of what looks like a tree, possibly reaching for some food. This figurine came in a pair; the two were excavated from what was called the “Great Death Pit” in the Royal Cemetery at Ur, lying not too far apart from each other.

The British excavator, Leonard Woolley chose the name, Ram in a Thicket, because it resembled a reference from the book of Genesis, 22:13, in the Bible when Abraham was about to sacrifice Isaac, his son:

“Then Abraham looked up and saw a ram caught by its horns in a thicket. So he took the ram and sacrificed it as a burnt offering in place of his son”.

The figure measures 45.7 x 30.48 centimeters and is composed of silver, gold, lapis lazuli, shell, copper alloy, red limestone, and bitumen. An interesting fact about bitumen (or asphalt) is that the Sumerians used it as an adhesive. The Sumerian word for bitumen is believed to be esir.

If we look more closely at the Ram in a Thicket, we will notice it has a wooden core. The head and legs are covered in gold leaf that is attached to the wood; the adhesive qualities of bitumen keep it pasted on. The ears are made from copper. The horns are made from lapis lazuli.

From the dorsal view of the ram, there is what appears to be a fleece covering its upper shoulder area, which is also made from lapis lazuli; the fleece that covers the rest of its body is made from shell, also stuck on using bitumen. The ventral view shows the ram’s stomach area is made from a silver plate, but this is reportedly oxidized and unrepairable. The ram’s genitals are made from gold.

The tree itself is golden in color, made from gold leaf with gold flowers at the end of each branch. Both the ram and tree are on a small rectangular platform made from shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone. It appears like a mosaic pattern covering the base. There is also a small tube protruding from each ram’s upper shoulder area, believed to have possibly been for supporting an object like a bowl.

Currently, the rams are in two different museums, one is in the British Museum’s Mesopotamia Gallery in London. The other ram is in the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

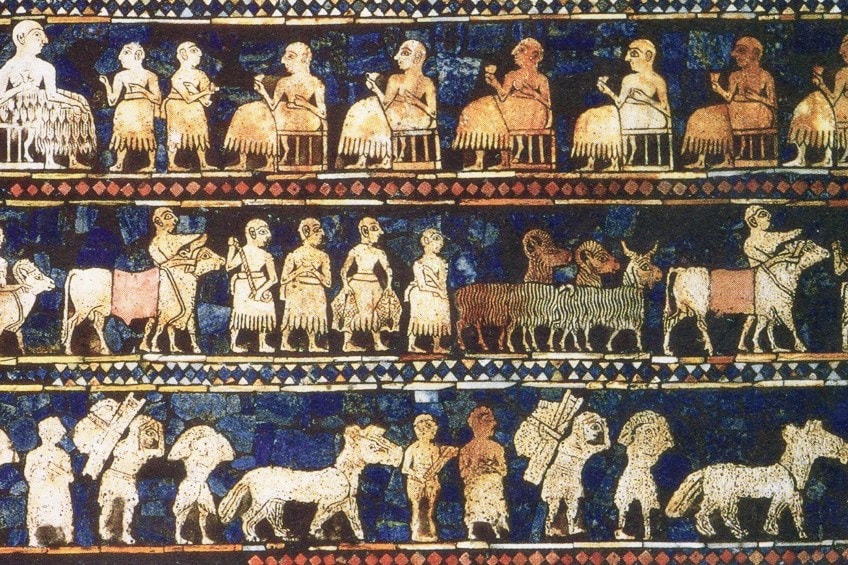

Standard of Ur (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC)

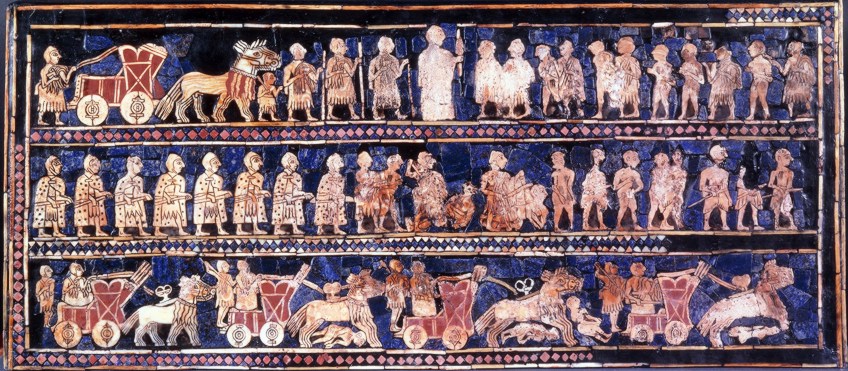

The Standard of Ur (c. 2 600 BC to 2 400 BC) was excavated from the Royal Cemetery at Ur, also during the excavations led by Leonard Woolley. It was found near the shoulder of a man in the corner of a tomb believed to have been dedicated to Ur-Pabilsag, a king during the First Dynasty of Ur during the 26th century BC.

Woolley suggested the item was used as a standard, which is related to someone carrying an image that relates to a person of high status like a king in this regard.

However, there has been debate as to the real function of this item, some also suggested it was used as a storage box or a sound box. The item was considerably damaged over the centuries from the weight of the soil and the decay of the wood. There have been restoration attempts made to make it appear how it could have looked when it was used.

As we see it now, it is a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimeters in width and 49.53 centimeters in length. There are inlays along each length and end of the box. These are made from red limestone, lapis lazuli, and shell, in a mosaic format. The box’s length is divided into three panels.

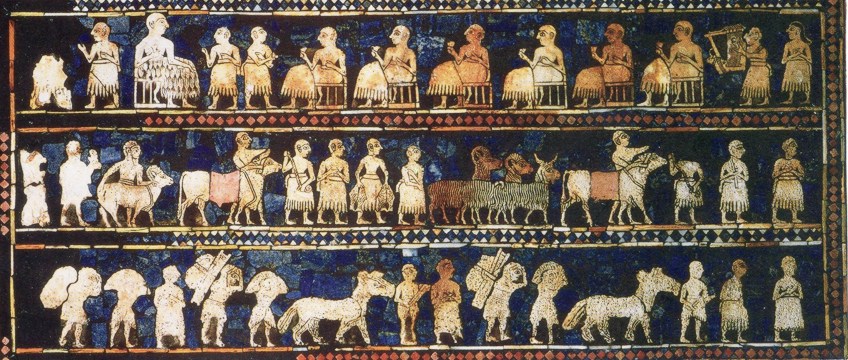

What is so unique about this box is that the mosaic inlays are depicted in detail telling a visual story. The narrative and subject matter have been titled “War” and “Peace” because there are figures that relate to the military and other figures that appear to be involved in a banquet.

If we look closer, the “War” panel depicts various figures from the Sumerian army. In the top panel, from the left, we see a man standing by a wagon pulled by four donkeys. There are members of the infantry with cloaks and spears and a central, taller, figure, possibly the king, holding a spear awaiting a procession of oncoming prisoners from the right. Each prisoner seems to be naked and possibly escorted by members of the infantry.

The middle panel depicts what appears to be more members of the army and perpetrators being struck and killed. From the left, there are eight men wearing the same military garments (cloaks and helmets) with weapons. It appears as if they are approaching an ongoing battle that we see depicted on the right side of the panel. The lower panel of the box depicts four wagons led by four donkeys for each. In each wagon, there is a driver and a soldier ready to fight. We will also notice under three of the wagons are dead bodies of the enemies killed from the wagon’s weight and those on it.

The wheels depicted on the wagons are solid structures, a telling portrayal of what it could have looked like in real life.

There is also a dynamism portrayed in the donkey’s stances; from the left, the first wagon with donkeys is seemingly walking, the wagon and donkeys in front of them seem to be going at a bit of a faster pace, otherwise referred to as a canter. The third set of wagons and donkeys appear to be galloping and the last set of donkeys are rearing.

If we look at the “Peace” panels, starting from the top panel, we will see the king on a stool to the left. There are six figures, also seated, holding cups in their right hands, all facing the king, who also holds a cup in his right hand. There are various attendants and a musician holding a lyre, standing as the second figure from the right side. In the middle portion of the “Peace” panel, we will notice various figures ushering in animals that appear to be rams and cows. Some figures also appear to hold fish.

The lower portion of the panel depicts figures with donkeys and packs on the backs, possibly of foodstuffs. These processions of figures from the middle and lower portion of the panel could be on their way to the banquet with offerings towards the feast.

The Queen’s Lyre (c. 2 600 BC)

The Queen’s Lyre (c. 2 600 BC) was found amongst numerous other lyres from the Royal Cemetery at Ur. With a height of 112.50 centimeters and a length of 73 centimeters, this Lyre was found at Queen Puabi’s gravesite. The wood that composed it was damaged from all the years in the gravesite, but it has been restored in various parts. Leonard Woolley reportedly found two lyres in the queen’s grave.

When we look at it more closely, we see the music box is in the shape of a bull. The head and face are gold with lapis lazuli composing the head’s hair, the “beard” of hair under the bull’s face, and its eyes, which are also made from shell. The two white horns are apparently not part of the original, ancient, figure, but modern additions that give us an indication of what it looked like.

As we move further down, what would theoretically be towards the ventral view of the bull’s body, but is really the curving of the music box, we see the similar mosaic panels made from the same material as the above Standard of Ur, shell, red limestone, and lapis lazuli.

This front panel is divided into four squares, each depicting images.

The top image is an eagle with a lion’s head and spread wings with two flanking gazelles. The next image is described by various sources as “bulls with plants on hills”. However, when we look closely these appear like two rams standing on their hind legs reaching up a tree on some sort of basal mound. These are reminiscent of the Ram in a Thicket figurines.

The third square, so to say, depicts a figure with the body of a ram or bull and the torso of a man, holding up two Leopards (or Cheetahs?) by their hind legs. The last square depicts a lion busy sinking its teeth into a bull. There is also a tree shape in the background, similar in appearance to the two trees from the second square.

Warka (Uruk) Vase (c. 3 200 BC – 3 000 BC)

Warka is the modern name for the ancient Sumerian city that was called Uruk. The alabaster Warka Vase (c. 3 200 BC to 3 000 BC) is another example of the beauty of Sumerian carvings. The measurements have been debated for this vessel, as a field book entry from 1934 (when it was found) stated it was around 96 centimeters high, whereas other sources state it is 105 and 106 centimeters high.

Regardless of its measurements, it is safe to say it is around one meter tall. Its diameter is measured as being 36 centimeters.

The Warka Vase was found by a group of German excavators around the years 1933 to 1934. It was in the temple dedicated to the Sumerian goddess called Inanna. She presided over beauty, sex, love, justice, and war. The Sumerian carvings are done as relief carvings and span around the vessel divided into four panels, otherwise known as registers.

Each register depicts different figures and objects from nature; the bottom panel is filled with water at the bottom and growing crops of what appears to be barley and wheat amidst reeds; the second panel depicts rams and ewes. In the third panel, we see nine nude figures of men carrying containers or baskets with food in it. The top panel depicts more characters, including the goddess Inanna and the king.

There are differing ideas as to what narrative the subject matter portrays; some suggest it is a marriage between the king and queen and others that it is a celebration of the queen. This vessel is housed in the National Museum of Iraq.

Sumerian Architecture

The Sumerians’ architecture is another important part of not only Sumer culture, but Sumer art. Most buildings were made of clay bricks, a widely spread material. Sumerians were also known as one of the first cultures to undertake urban or city planning. Buildings ranged from houses to palaces and there were different functions, for example, commercial, civic, and residential.

As described from a few examples above, we will typically find a temple as a central building.

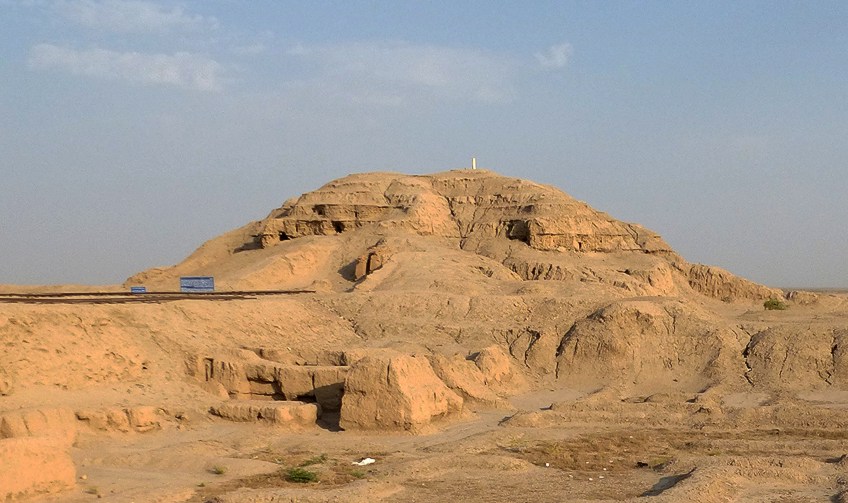

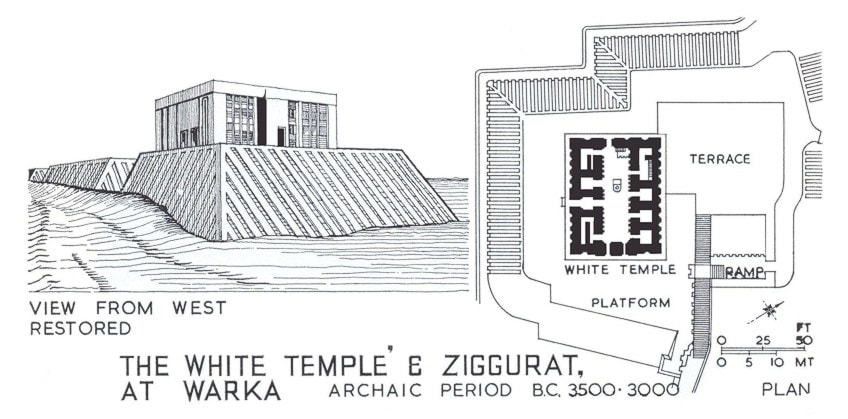

The Ziggurat was an important structure, in the shape of a pyramidal tower, or “raised platform”. It was built to venerate the dedicated god or goddess, and a reminder of the political leaders who acted on behalf of that deity, this was a large part of the Sumerian theocratic system.

An example of the above was the White Temple (c. 3517 BC to 3358 BC) built on the Anu Ziggurat in Uruk. Anu was the god of the sky. However, almost over 30 such temples are recorded to exist in various locations around Mesopotamia.

From Writing to Wheels: The Sumerians Remembered

The Sumerian civilization was succeeded by the Akkadians, led by the ruler Sargon of Akkad, from 2334 BC to 2154 BC. After the Akkadian Empire fell there was a period referred to as a “Dark Age” after which there was a resurgence in Sumerian culture with the beginning of the Third Dynasty of Ur (2112 BC to 2004 BC). This was also called the Neo-Sumerian period. It has been compared to a sort of “Golden Age” of the Sumerian Civilization and revival of arts, especially religious arts.

The Sumerians were undoubtedly advanced in many ways, setting the stage for many civilizations to come in so many disciplines in life like art, science, religion, politics, agriculture, and more. They have been lauded as some of the greatest ancient inventors, think of the wheel and writing. And now in our modern-day, we still remember them as a civilization rich in culture, adorned with gems of wisdom just like the art they created.

Take a look at our Sumerian art period webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

When Was the Sumerian Period?

Sumer was one of the earliest Mesopotamian civilizations originating before the Akkadian Civilization. Sumer is in the southern part of Mesopotamia and is believed to have been settled around 4 500 BC to 4 000 BC.

What Does “Sumer” Mean?

The name Sumer was given to the Sumerians by the Akkadians. “Black-headed people” or “Black-headed ones” is what the Sumerians used as their name for themselves. The word Kengir, meaning “Country of the Noble Lords” was the name the Sumerians used for their land.

What Kind of Art Was Created in Sumer?

The Sumerians created art from different materials like semi-precious stones, shells, wood, red limestone, metals like gold, silver, and copper, to name a few. These were all used in Sumer paintings and mosaics. Sumerian statues, sculptures, figurines, pottery, and various other objects were also discovered in large quantities by various archaeological excavations. The Sumerians’ architecture and tablets to write on in the cuneiform script were mostly built using clay as this was a widespread and naturally occurring medium.

What Was the Purpose of Sumerian Art?

Sumerian art was beautifully decorated with ornamentations and served religious and sacred purposes. Many of the Sumer art objects were discovered from gravesites and were buried with their respective owners. Temples were important structures and were given great care in construction for the purposes of venerating respective deities.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, “Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art.” Art in Context. December 8, 2021. URL: https://artincontext.org/sumerian-art/

Meyer, I. (2021, 8 December). Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/sumerian-art/

Meyer, Isabella. “Sumerian Art – The Pottery, Carvings, and Architecture of Sumer Art.” Art in Context, December 8, 2021. https://artincontext.org/sumerian-art/.