“Venus de Milo” Sculpture – Discover the Famous Statue Without Arms

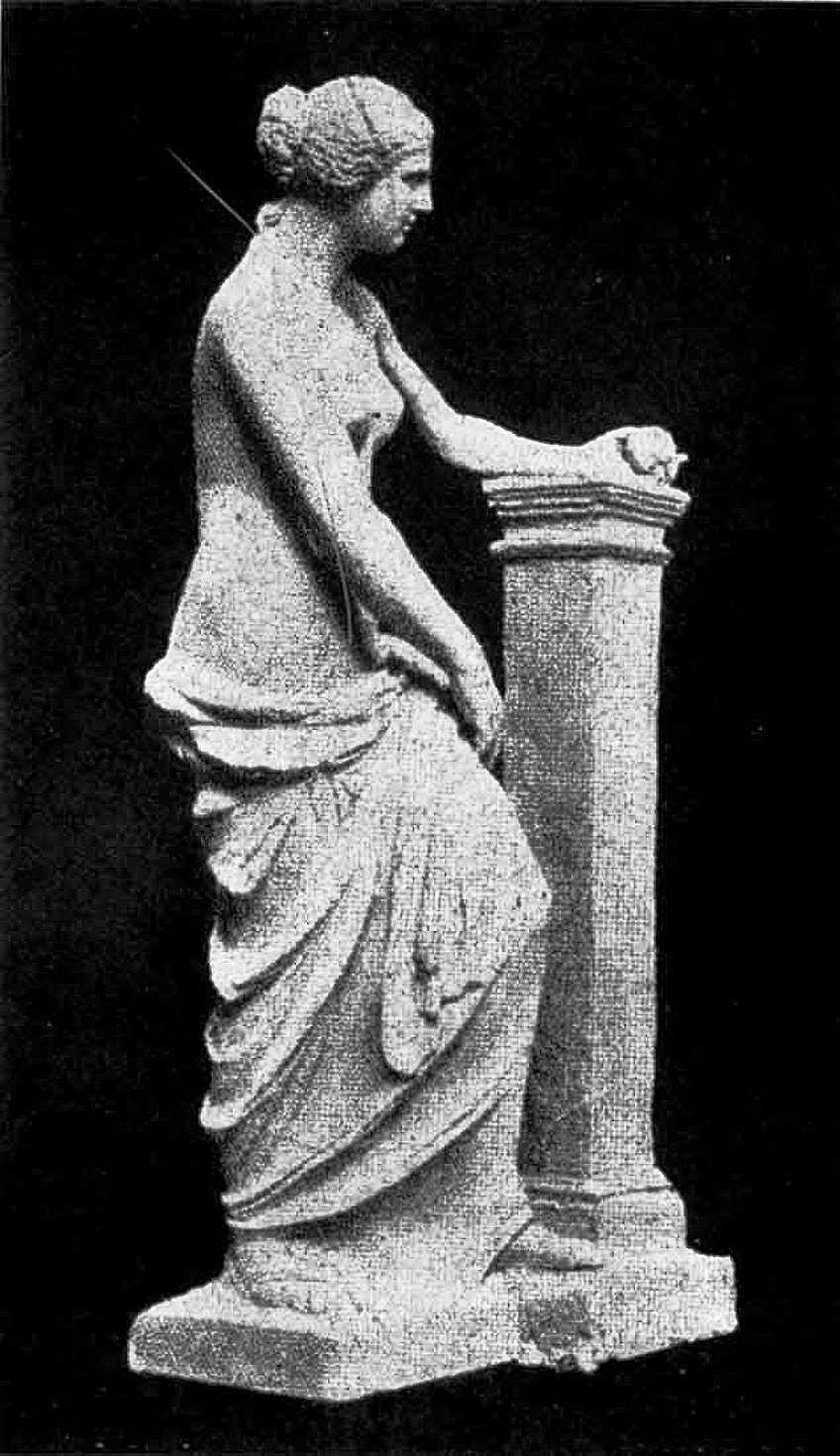

Produced in the Hellenistic art period, the Venus de Milo sculpture is believed to have been created by Alexandros of Antioch between the years 150 BC and 125 BC. The famous statue without arms is thought to portray Venus in Rome, or Aphrodite, as she is known in Greece. Others believe it is a representation of Amphitrite, the sea goddess.

The Venus de Milo Sculpture

| Date Completed | c. 150 BC – 125 BC |

| Medium | Parian Marble |

| Dimensions | 204 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre, Paris |

Since its discovery in 1820 on the little Greek island of Melos in the Aegean Sea, this beautiful goddess sculpture has captivated art enthusiasts for over two hundred years. It is on public exhibit in the Louvre Museum’s gallery of Greek sculpture in Paris and is perhaps the most well-known sculpture in the history of art.

The beautiful statue without arms was previously credited to the sculptor Praxiteles, but it is now largely accepted that the figure was constructed sooner, and is rather the art of Alexandros of Antioch, predicated on the notation on its base.

History of the Venus de Milo Sculpture

The Venus de Milo sculpture was discovered in Melos, a Greek island in the southern Cyclades region. It was discovered in a meadow by a young peasant named Yorgos Kentrotas, concealed in a wall crevice among the remains of Milos.

The statue was found in two sections: the torso and the draped legs. A second left arm clutching an apple, as well as an engraved plinth with a definite connection to a craftsman named “Alexandros from Anchiochia on the Meander,” were unearthed nearby.

A French naval officer from the French armada grounded nearby assisted the farmer in retrieving the monument. As word of the discovery spread, Jules Dumont d’Urville alerted the French Consul. In response, he organized for the sculpture to be brought to France, where it was delivered as a gift to King Louis XVIII, who later gave it to the Louvre. Yet despite this claim, Yorgos Bottonis and his son Antonio are named as the true discoverers in other parts of the world.

The location of the discovery, according to Paul Carus, was “the remnants of an ancient auditorium in the proximity of Castro, the island’s capital,” and Bottonis and his son “unintentionally discovered a narrow cave, skilfully covered with a massive slab and obscured, which encapsulated a wonderful marble sculpture in two pieces, along with several other marble pieces, in February 1820.” He appears to have based his claims on an editorial he read in Century Magazine.

According to Edward Duyker, the Australian historian who cites a letter sent by Louis Brest in Milos in 1820, the discoverer of the sculpture was Theodoros Kendrotas, who was mistaken for his son Yorgos, who subsequently claimed responsibility for the discovery. According to Duyker, Kendrotas was collecting stone from a destroyed chapel on the outskirts of his property — terraced terrain that had formerly been part of a Roman gymnasium.

The statue was discovered in two big sections, together with multiple head-topped pillars, remains of the left arm and hand grasping a fruit, and an engraved plinth. The Venus de Milo sculpture was deemed a great artistic find when it was discovered in 1820, but it did not become an icon until much later. However, the precise circumstances surrounding her discovery remain unknown.

When Napoleon’s plundered art collection was transferred to their nations of origin, the Louvre, and hence French art as a whole, sustained significant losses. Some of the museum’s most prominent artifacts, including Laocoon and His Sons and the Venus de Medici, were lost.

Amphitrite or Aphrodite?

When she was originally received at the Louvre, it was recommended that her missing arms be reconstructed, but the proposal was later dropped because of concerns that it would change the character of the piece. The statue’s absence of arms made it difficult to recognize.

Many portrayals of Greek gods and goddesses have ‘attributes’ (items or natural elements) clutched in their hands; therefore, this sculpture raises the question: is she the sea goddess Amphitrite, who is particularly revered on the island of Melos? Or is she Aphrodite, the deity of perfection, as her seductive, half-naked form could imply?

This second explanation, together with the jewelry she formerly wore, swung the scales in Aphrodite’s favor (Venus for the Romans). Another probable clue was discovered beside the figurine: a hand-sculpted from the very same Parian marble grasping an apple, which is an ornament of Aphrodite.

The Louvre

The Venus de Milo sculpture was first displayed at the Louvre in 1821, although her placement has moved numerous times since then. She was initially displayed at the Galerie des Antiques, where she may still be seen today. The emperor purchased his brother-in-law’s famed art collection, Prince Camille Borghese’s, in 1807. He instructed Pierre Fontaine and Charles Percier, the architects, to extend the newly built Galerie des Antiques to hold the collection.

The new rooms supplanted the royal apartments, but Percier and Fontaine entirely redesigned them, eliminating partition walls to open up the area and adding red and grey marble to contrast with the whiteness of the sculptures.

The dedication took place in 1811, five years before the famous statie without arms arrived. It first appeared at the Louvre in 1821, although its placement within the museum has shifted multiple times since then. She was initially displayed at the Galerie des Antiques, where she may still be seen today.

However, several problems emerged, including whether she should be presented alone or with other artworks. What type of foundation should she build on, and where should she stand it? Would it not be more suitable for her in the Grande Galerie amid the canvases?

After nearly two centuries, the statue was finally restored to the chamber where she was initially presented – and she now has pride of position, standing virtually alone in the center of the exhibition area to provide visitors a better perspective.

False Attribution

The museum was still mourning the departure of the Medici Venus, a famous work of classical antiquity that had been transferred to Italy following Napoleon’s loss at Waterloo in 1815. As a consequence, to increase the prestige of its new purchase, it was resolved to disregard the pedestal.

However, the pedestal had inscriptions naming Alexandros of Antioch as the artist. Despite this, the work was assigned to the sculpture to Praxiteles, one of the finest artists of the Classical period.

To achieve this, the officials began a large publicity effort touting the value of the piece, which they cleverly dated to Praxiteles’ Classical period – a move that slowed the appearance of an appropriate scholarly appraisal of the sculpture.

From then onwards, the Venus de Milo has been ascribed to the late Hellenistic art period and assigned to Alexandros of Antioch, a sculptor far lees as renowned as Praxiteles.

Analysis and Characteristics of the Venus de Milo Sculpture

Without its pedestal, the structure stands 6 feet 8 inches tall and is composed of Parian marble. Aphrodite, the Greek goddess of sensual love and elegance, is said to be depicted. According to preservation experts, the monument was fashioned from two slabs of Parian marble and is made up of several components that were carved separately before being joined together with vertical pegs.

Characteristics

Unfortunately, the figure’s limbs and initial pedestal have been lost practically since the artwork arrived in 1820 in Paris. This was primarily due to authentication issues since the neighboring portions of the left hand and arm were not deemed to belong to the monument when it was initially restored due to their general “rougher” appearance.

Despite the difference in polish, specialists are now confident that these additional pieces were part of the initial artwork since it was common practice at the time to spend less time on the sculpture’s less visible parts.

The arm in issue is generally unnoticeable to the casual spectator since it is above eye level. Venus de Milo‘s uniquely carved right arm hung across the torso, with the right hand resting on the raised left knee, gripping the drapery draped over the legs, according to sculpture repair experts.

At the same time, the fruit was held at eye level by the left arm. Scholars debate whether the goddess was looking at the fruit she was holding or out into the distance. The statue would have been stained with color pigments to give it a more lifelike look in its natural condition, then embellished with a bracelet, earrings, and headpiece before being put in a niche inside a shrine or gymnasium. Nevertheless, no evidence of the paint remains now, and the only indications of any metal jewelry are the fastening holes.

To begin, take note of the juxtaposition between the smooth bare flesh of the chest and the rippling pattern of the draperies surrounding the legs. Second, take note of the spiral composition, which consists of a minor rotation of the body – from the pelvis to the shoulder – paired with an outer thrusting of the right hip, culminating in an intriguing S-shaped attitude. Third, take note of the torso’s tiny size.

Lastly, the drapery, which seems to fall off totally, adds an unmistakable touch of sensual tension. These four stylistic characteristics all emerged during the late Hellenistic art period. As a result, the work is perceived as a delicate blend of older and later styles.

Mythology and Enduring Mystery

Most academics believe the Venus de Milo sculpture depicts the Greek divinity Aphrodite and also the story of the Paris Judgment. In this story, the goddess of Discord bestows a golden apple on a young Trojan prince named Paris and instructs him to present it to the most attractive of three candidates: Athena, Aphrodite, and Hera. Aphrodite won the beauty pageant by paying Paris with the affection of Helen of Sparta, the most attractive human woman, and was granted the apple.

During the 19th century, a number of art experts lauded the Venus de Milo as one of the greatest masterpieces of Greek art.

This was because it symbolized the pinnacle of feminine beauty and elegance – not least because of its amazing marriage of majesty and grace. Although times and preferences change – limbless Greek sculptures are not as popular in the 21st century – the deity retains much of her enigma. Although she is thought to symbolize Aphrodite, her sensuous, feminine curves suggest that she might also be the sea goddess Amphitrite, who was adored on the island of Milo at the time.

Likewise, given its similarities to the “Aphrodite of Capua”, the Louvre believes it might be a Roman duplicate of an authentic Greek statue dating back to the late 4th century.

World War II Evacuation

Jacques Jaujard, the director of the French Musées Nationaux, chose to plan the removal of the Louvre collection of art to the provinces before the commencement of the German onslaught during World War II, expecting the surrender of France.

“The Winged Victory of Samothrace”, as well as the famous statue without arms, were held in Château de Valençay, which was saved from German occupation on technical grounds.

Modern Use

The sculpture has had a significant effect on masters of contemporary art, with two notable instances being Salvador Dalí’s works The Hallucinogenic Toreador (1970) and Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936), The sculpture was once part of the emblem of the ASPS (the American Society of Plastic Surgeons).

The German publication “Focus” published a doctored picture of Venus flipping Europe off in February 2010, prompting a slander case against the writers and the publisher. The Greek court ruled them not guilty.

Cultural References

As one of the world’s most famous pieces of art, the Venus de Milo sculpture has been mentioned several times in popular culture. The depiction of how the statue purportedly lost its limbs is a typical humorous prank. Charlie Drake did a comedic performance in 1960 in which museum staff accidentally broke off the arms while packaging it. Similarly, a comedy in the 1964 film Carry On Cleo pretended to demonstrate how the sculpture lost its arms.

The eponymous character in the 1997 Disney picture, “Hercules”, skims a stone on water and accidentally smashes both arms of the sculpture.

The 1966 parody espionage thriller The Last of the Secret Agents featuring Steve Rossi and Marty Allen, revolves around a scheme to steal the sculpture. The Venus de Milo is frequently showcased and satirized in television programs, such as The Tick‘s episode in which the bad guys rob a museum of art, and in Only Fools and Horses, in which one character shows another a model of the figurine, remarking that there are sick-minded individuals in the universe who would make such a monument of a disabled person.

The statue without arms has been a huge success since it was discovered by archeologists. The statue is famous for its extraordinarily advanced age, having been carved in sections and combined into a single sculpture. Experts believe it was carved from marble around 100 BCE. The deity was also formerly decked with jewels, as shown by attachment holes. Because her arms have never been located, the Venus de Milo sculpture at the Louvre remains a mystery to this day.

Take a look at our statue of Venus webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Does the Statue Without Arms Portray?

It was suggested that her missing arms be recreated when she was first received at the Louvre, but the request was subsequently discarded due to worries that it would damage the piece’s essence. Because the statue lacked arms, it was impossible to identify. Many depictions of the goddesses and gods from ancient Greece have so-called attributes in their hands, therefore this statue begs the question: is she perhaps Amphitrite, the renowned sea goddess who is especially adored on the island of Milos? Or might she be Aphrodite, the goddess of perfection, as her alluring, half-naked appearance could suggest? This second theory, together with the jewelry she used to wear, tipped the scales in favor of Aphrodite (Venus to the Romans).

Who Created the Venus de Milo Sculpture?

To boost the reputation of its recent acquisition, the Louvre Museum opted to ignore the pedestal, which had inscriptions designating Alexandros of Antioch as the artist, and instead gave the sculpture to Praxiteles, one of the greatest Classical artists. To accomplish this, authorities launched a massive public relations campaign praising the sculpture’s importance, which they skillfully dated to Praxiteles’ Classical era – a move that slowed the appearance of a proper scientific evaluation of the artwork. Since then, the Venus de Milo has been attributed to Alexandros of Antioch, a lesser-known stone sculptor, and placed in the late Hellenistic art period.

Where Is the Venus de Milo Sculpture?

Today, the Venus de Milo may be seen at the end of a long succession of apartments in the Louvre in Paris, nearly alone in her grandeur. The exquisite red marble design comes from Napoleon I’s rule in the early 19th century. The emperor purchased his brother-in-law, Prince Camille Borghese’s, famed art collection in 1807. He instructed the architects Pierre Fontaine and Charles Percier to extend the newly built Galerie des Antiques to hold the collection.

Isabella studied at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and graduated with a Bachelor of Arts majoring in English Literature & Language and Psychology. Throughout her undergraduate years, she took Art History as an additional subject and absolutely loved it. Building on from her art history knowledge that began in high school, art has always been a particular area of fascination for her. From learning about artworks previously unknown to her, or sharpening her existing understanding of specific works, the ability to continue learning within this interesting sphere excites her greatly.

Her focal points of interest in art history encompass profiling specific artists and art movements, as it is these areas where she is able to really dig deep into the rich narrative of the art world. Additionally, she particularly enjoys exploring the different artistic styles of the 20th century, as well as the important impact that female artists have had on the development of art history.

Learn more about Isabella Meyer and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Isabella, Meyer, ““Venus de Milo” Sculpture – Discover the Famous Statue Without Arms.” Art in Context. April 20, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/venus-de-milo-sculpture/

Meyer, I. (2022, 20 April). “Venus de Milo” Sculpture – Discover the Famous Statue Without Arms. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/venus-de-milo-sculpture/

Meyer, Isabella. ““Venus de Milo” Sculpture – Discover the Famous Statue Without Arms.” Art in Context, April 20, 2022. https://artincontext.org/venus-de-milo-sculpture/.