“The Stone Breakers” Gustave Courbet – A History and Analysis

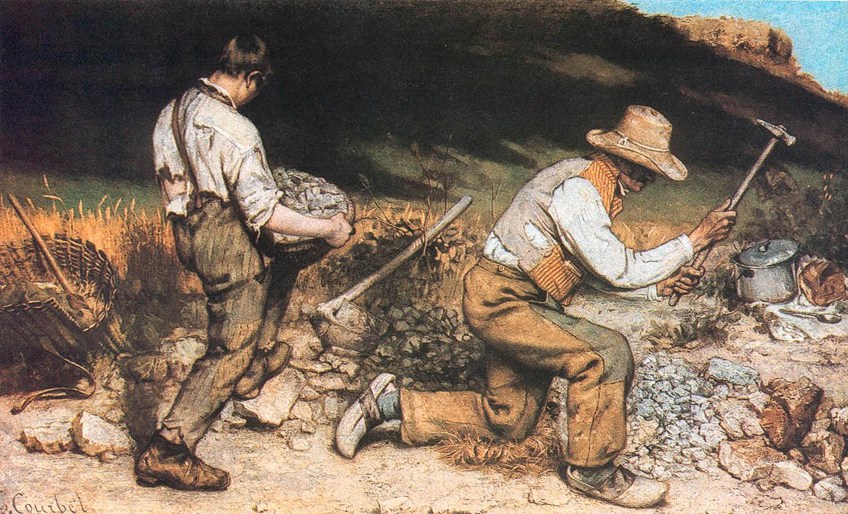

The Stone Breakers by Gustave Courbet is a famous Realism painting created in 1849. The Stone Breakers (1849) portrays two poor workers in the process of breaking rocks apart. The Stonebreakers painting was first displayed in the 1850 edition of the Paris Salon. Gustave Courbet’s Realism artworks always depicted everyday scenes of life. In this article, we will cover Gustave Courbet’s The Stonebreakers analysis and history.

The Stone Breakers by Gustave Courbet in Context

The Stone Breakers (1849) by Gustave Courbet was created to portray the intense labor that the poorer portion of the population endured daily. No facial features were depicted in order for the figures to represent every person and not a particular individual. In February of 1945, the Stonebreakers painting was destroyed when allied forces bombed a vehicle that was transporting the painting as well as more than 150 other works of art.

| Artist | Gustav Courbet (1819 – 1877) |

| Dimensions | 170 cm x 240 cm |

| Medium | Oil Painting on Canvas |

| Year | 1849 |

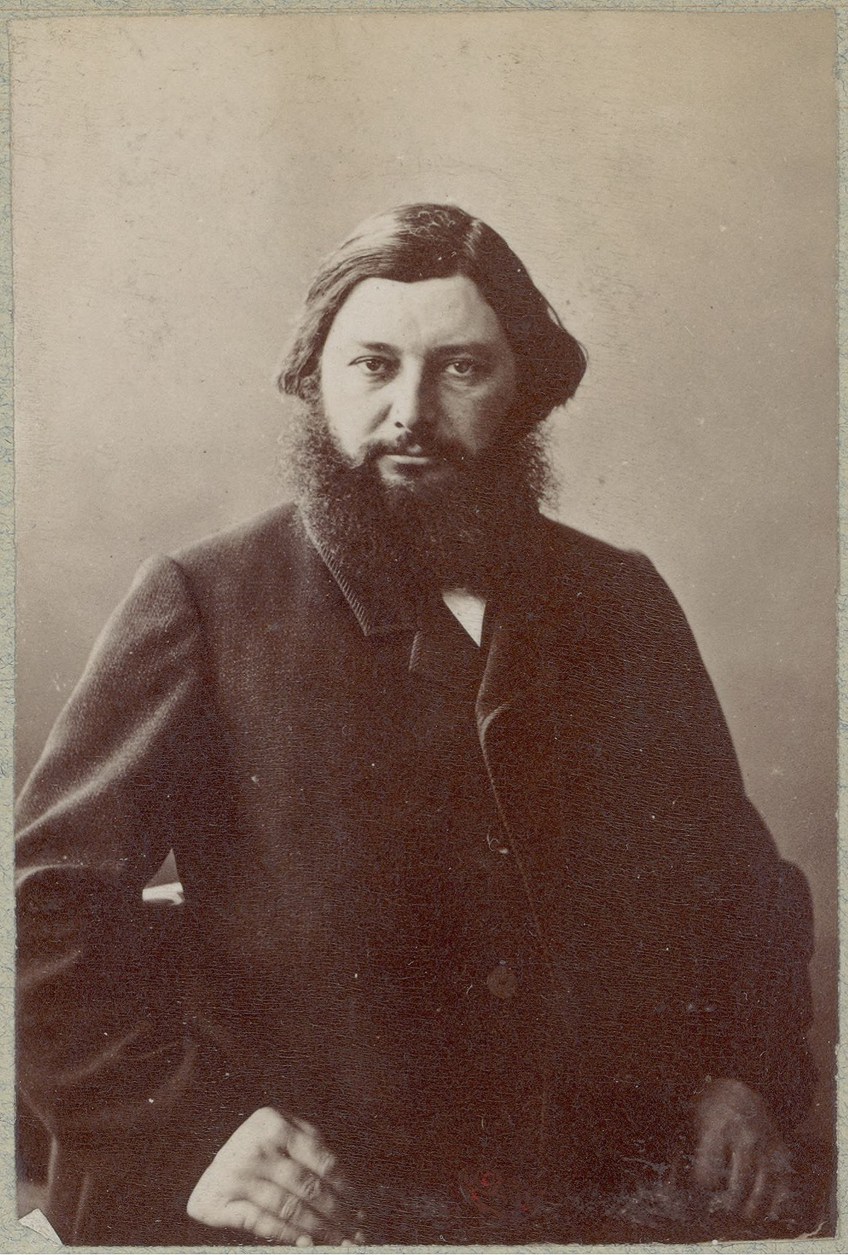

An Introduction to Gustave Courbet

Gustave Courbet was a pivotal figure in the mid-19th-century birth of Realism. Spurning the French Academy’s traditional and dramatic aesthetics, his painting concentrated on the actual truth of the items he viewed – even if that actuality was simple and flawed. As a devoted Republican, he regarded his Realism as a method of defending the farmers and rural folk of his birthplace. He was notable for his reaction to the political changes that engulfed France during his life, and he died while exiled in Switzerland after being declared liable for the expense of reconstructing Paris’ Vendome Column.

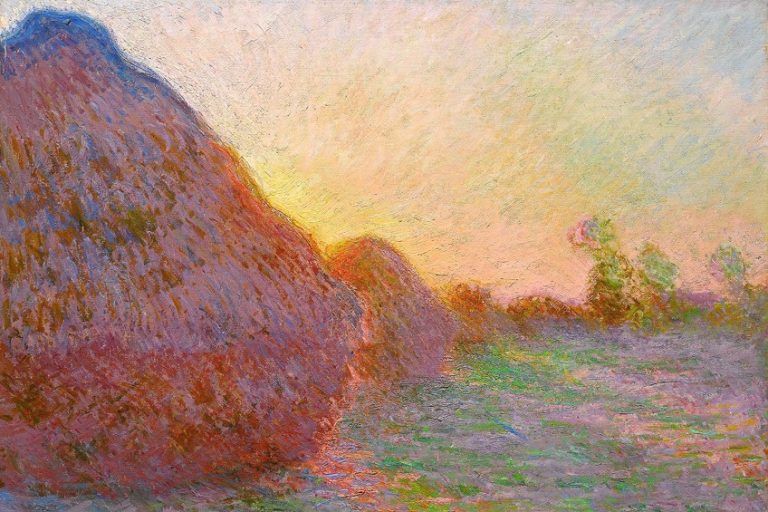

His oeuvre, nevertheless, has recently been viewed by historians as a key precursor to other early modernist painters such as Claude Monet and Édouard Manet.

Gustave Courbet’s Realism may be regarded as part of a larger investigation into the natural universe that captivated academia in the 19th century. But it was his disdain for the French Academy’s constrictions that motivated him the most in his own field of painting. He disregarded Romantic or Classical approaches in favor of taking lowly images of rural life – themes normally associated with small genre paintings – and transforming them into material for grand historical painting. He became well-known as a result of this. Courbet momentarily gave up art to work in administration during the Paris Commune of 1871. This was typical of his left-wing sympathies.

His art was not openly ideological, but in the backdrop of the period, he was not dismissed because he communicated notions of justice by making heroes of ordinary people, depicting them in large size, and refusing to hide their flaws.

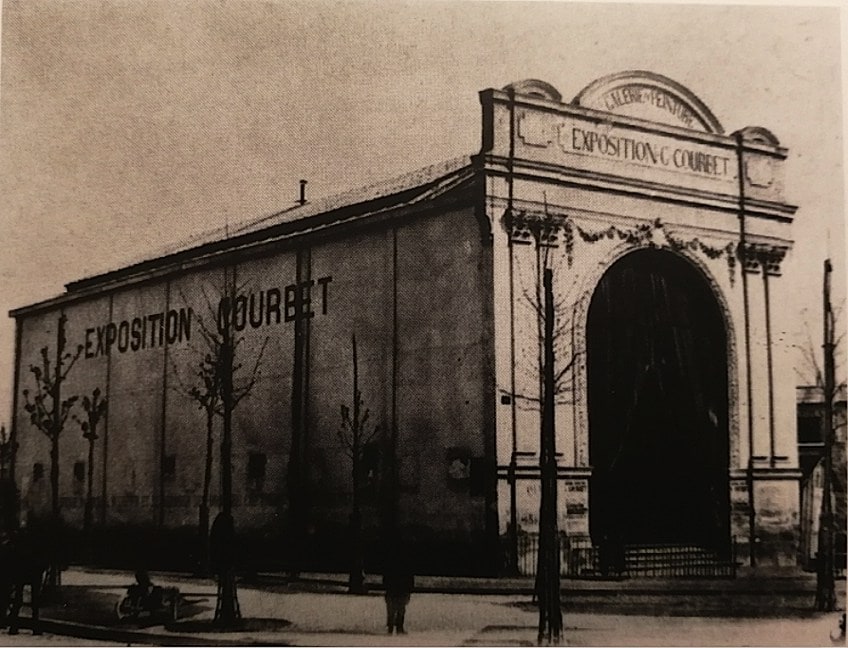

Courbet frequently landed on compositions that appeared collaged and primitive to conventional tastes while wiping away the jargon of Academic art. He also discarded precise modeling at moments in favor of generously layering paint in fragmented specks and chunks. Such artistic developments earned him the admiration of succeeding modernists who advocated for unfettered arrangements and enhanced surface complexity. Rather than relying only on the state-run Salon structure, Courbet established the solo exhibition as a private economic business, a strategy that many later rogue painters adopted.

The Influence of Gustave Courbet’s Realism

Though never a cohesive movement, Realism is regarded as the first contemporary art movement, rejecting conventional forms of art, literature, and social structure as obsolete in the aftermath of the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution. Starting in the 1840s in France, Realism changed painting by broadening perceptions of what constitutes art.

Working in a turbulent era defined by revolution and vast social upheaval, Realist artists replaced classical art’s idealized ideas and intellectual contrivances with real-life happenings, giving the edges of civilization the same weight as big historical paintings and analogies.

Their decision to incorporate ordinary life into their paintings was an early indication of the avant-garde aim to integrate art and reality, and their abandonment of pictorial conventions such as viewpoint foreshadowed the various 20th-century interpretations and new definitions of modernist art.

Realism is often regarded as the birth of contemporary art. Essentially, this is because it believed that ordinary life and the modern world were appropriate topics for art. Metaphysically, Realism supported modernism’s revolutionary goals, seeking new truths via the reconsideration and shattering of established belief and value structures.

Realism was focused on the societal, financial, economic, and cultural structures of life in the mid-19th century. This resulted in frank, often “ugly” depictions of life’s terrible experiences, as well as the use of dark, earthy hues that challenged high art’s absolute beauty ideals.

Realism was the very first artistic movement that was deliberately anti-institutional and contrarian.

Realist artists targeted the aristocracy and royalty, who frequented the art market, with their social mores and ideals. Although they proceeded to submit pieces to the formal Academy of Art Salons, they were not afraid to stage unofficial exhibits to brazenly expose their works. After the Industrial Revolution’s expansion of newspaper publishing and media outlets, Realism introduced a new notion of the painter as a self-publicist. Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, and others actively sparked controversy and exploited the media to boost their popularity, a practice that persists to this day among creators.

Realism, like Romanticism, was a vast cultural movement that had its roots in philosophy and literature. Gustave Courbet was its most notable exponent in painting. His Stonebreakers painting was a gigantic representation of workmen as he had seen them. Courbet created this painting without any obvious emotion, instead of allowing the picture of the two figures to reflect the sentiments of misery and tiredness that he was attempting to represent. By depicting these characters with a nobility all their own, Courbet expresses compassion for the laborers and hatred for the wealthy elite. Proudhon, a Socialist theorist, defined it as a rural emblem. But for Courbet, it was only a recollection of something he had seen: two people cracking stones by the road.

He informed his art journalist colleagues Francis Wey and Champfleury: “It is not often that one sees such a comprehensive depiction of destitution, and so I had the inspiration for work right then and there. I invited them to my workshop the very next morning.”

Many of Gustave Courbet’s Realism artworks depict ordinary people and situations in regular French life. Courbet portrayed these common folk to represent the French citizens as a political body. Courbet’s republicanism shone through in his art in this way. Courbet depicted everyday people and settings without the glitz that other French artists at the period put into their paintings. As a result, Courbet became recognized as the Realist movement’s leader.

Gustave Courbet’s The Stonebreakers: An Analysis

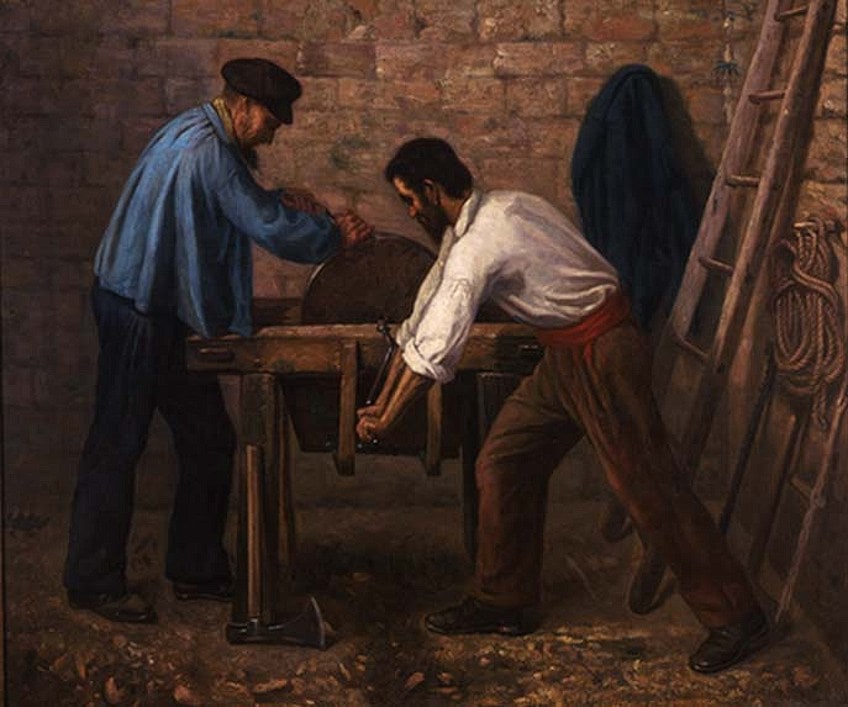

Gustave Courbet rode his family wagon down a route at Maisières, near his birthplace of Ornans in eastern France, in 1849. He walked by two laborers, a male, and a boy, who were crushing stones into pebbles for the roadbed. The artist summoned the duo to his workshop and had them stand for a portrait.

Subsequently, in a handwritten letter, he explained the artwork: “It is made up of two pitiful figures: one is an elderly person, an ancient machine stiffened by duty and age. His burnt head is protected by a straw hat that has become darkened by dirt and moisture. His arms appear springy, and he is clad in a coarse linen shirt. A tobacco bag made of a horn with bronze borders can be seen in his red-striped waistcoat. His hefty pants, which could stand on their own, expose a huge spot at the knee, sitting on a straw matting; through his old blue stockings, one can see his heels in his broken wooden shoes.

Next to him is a young man of around 15 years of age who is afflicted by scurvy. His shirt is a shambles of soiled linen, revealing his arms and side. A shovel, a primitive kettle in which they transport their lunchtime soup, and a slice of brown bread in a scrip are spread on the floor. All of this occurs in broad daylight, next to a roadside ditch. I didn’t make any of it up, my comrade.”

This was not Courbet’s first picture of unsophisticated, country peasants, but it became one of the most significant pieces in an art collective known as Realism.

Despite its epic dimensions, this painting focused on a basic, unheroic topic. Courbet’s approaches were similarly out of the ordinary. His models were not performers or skilled posers, as was more typical at the period, but rather the people the painter wished to depict.

His style was also out of date at the time. Romanticism was the dominant style of the time, emphasizing beauty, fantasy, and melodrama over reality. Courbet, along with fellow painters Jean-Francois Millet and Honoré Daumier, disregarded what they considered as creative aberrations and instead attempted to produce artworks that truly reflected the reality as they experienced it.

Courbet destroyed the concept of an ageless and classless country ideal by showing characters whose economic and social distinctiveness was reinforced by their tangible weight and physical effort when the picture was displayed at the Parisian Salon of 1851.

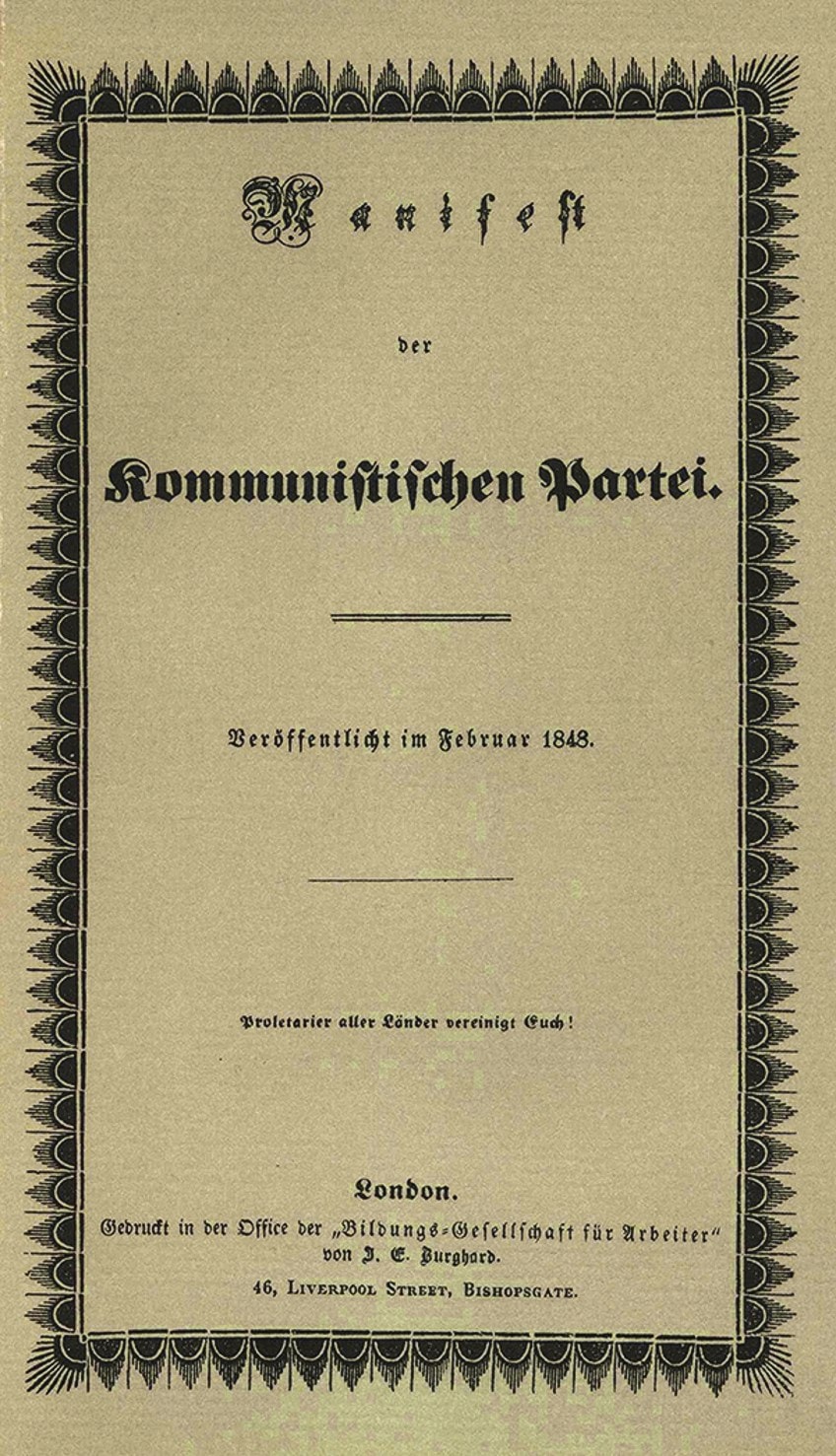

Some reviewers dismissed the painter, whereas others, such as France’s prominent Romantic artist Eugene Delacroix, saw him as a pioneer and a reformer. Indeed, the image, which was made just after the eventful year of 1848, which witnessed uprisings in the Netherlands, France, Germany, the Austrian Empire, Poland, and Italy, as well as the publishing of Friedrich Engels’ and Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto, encapsulated the zeitgeist of the era.

Mid-century unsentimentalized portrayals of the working poor, regardless of whether rural or metropolitan, were irrevocably connected to the political uprisings of 1848 and thus conceivably worrisome, such as Courbet’s The Stonebreakers, with its monumentalized laborers pushed into the center, their bodies contorted and uncomfortable as they work tirelessly at their arduous undertaking.

These farmers are not soothingly attractive tones hidden in a profusion of nature, but magnificently sized and unidealized people, harsh and genuine in their depictions and at variance with scholastic artwork’s intended conclusion. Courbet, Daumier, and others were labeled as Realists, and in 1855, Courbet penned a brief essay that became known as The Realist Manifesto.

In it, he declared that he did not wish to “attain the futile objective of art for the sake of art,” but rather “to interpret the traditions, thoughts, and manifestations of my time according to my own assessment of it, to be not an artist but a man, to produce living paintings, that is my ambition.”

Paradoxically, works like The Stonebreakers painting are significant for their foresight as much as their realistic description of their period, stressing the importance of class disparities that suggest that future fights will be tied to the new circumstances arising in cities. Realism foreshadowed the rural landscapes of Van Gogh and Cézanne, the work of American artists such as Edward Hopper and George Bellows, the works of photographers like Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, and more openly instructional social art groups such as Social Realism.

Contrasting Millet, who was known for representing industrious but glorified farmers in works such as The Gleaners (1857) by Jean-François Millet, Courbet shows humans in shredded and ragged attire. Moreover, unlike Millet’s use of aerial view in The Gleaners to transport us deep into the rural areas of France during the yield, the two quarry workers in Gustave Courbet’s Realism painting are arranged against a low hill typical of the rural French towns in which the painter was brought up and spent much of his time.

In the top right corner, in which a tiny spot of dazzling blue sky emerges, the slope rises to the peak of the canvas. This has the effect of isolating these workers and creating the impression that they are economically and culturally confined. The gleaners’ rounded backs reflect one another in Millet’s picture, producing a composition that feels united, whereas Courbet’s figures appear disconnected.

Courbet wanted to portray what is “true”; thus he represented a person who appears to be too old and a youngster who appears to be too young for such back-breaking activity. This is not meant to be a heroic tale; rather, it is supposed to be an authentic depiction of the abuse and deprivation that was a regular element of mid-century French rural life.

And, as with so many excellent creations of art, there is a strong connection between the storyline and the artist’s technical selections, which include brushstrokes, structure, line, as well as color.

Courbet’s brushstrokes, like the rocks themselves, are rough – rougher than one might anticipate for the mid-19th century. This shows that the artist’s painting approach was a deliberate criticism of the perfectly refined, sophisticated Neoclassicist technique that characterized French painting in 1848.

The unwillingness to emphasize the elements of the scene that would normally garner the greatest interest is perhaps the most distinguishing feature of Courbet’s technique. Typically, a painter would focus the majority of his or her attention on the hands, heads, and foregrounds. It’s not Courbet. If you look closely, you’ll note that he tries to be even-handed, paying equal attention to faces and rock. In these aspects, The Stone Breakers (1849) appears to lack essential artistic elements (such as a composition that picks and arranges, aerial viewpoint, and completion), and as a consequence, it feels more “genuine.”

And that concludes Gustave Courbet’s “The Stonebreakers” analysis and history. “The Stone Breakers” by Gustave Courbet is regarded as one of the first Realism paintings. The Stonebreakers painting was first displayed in the 1850 edition of the Paris Salon. “The Stone Breakers” (1849) portrays two poor workers in the process of breaking rocks apart. It was created by Gustave Courbet, a pivotal figure in the mid-19th-century birth of Realism.

Take a look at our The Stone Breakers webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Who Painted the Stonebreakers Painting?

Gustave Courbet, a French artist, created it. Rather than the conventional and dramatic aesthetics of the French Academy, his painting focused on the actual truth of the objects he saw – even if that truth was plain and defective. As a committed Republican, he saw his Realism as a means of preserving his birthplace’s farmers and rural inhabitants. He was noteworthy for his reaction to the political upheavals that swept over France during his lifetime.

Why Is The Stone Breakers (1849) Such a Popular Painting?

Courbet intended to depict what is “real,” thus he depicted an elderly person and a youngster who looks to be too young for such back-breaking work. This is hardly a heroic story; rather, it is an accurate representation of the brutality and hardship that was a frequent feature of mid-century French rural life. And, like with so many other exceptional works of art, there is a strong relationship between the tale and the artist’s technical choices, which include brushstrokes, structure, line, and color. The Stonebreakers painting is noteworthy for its foresight as well as its accurate depiction of their time period, emphasizing the relevance of class discrepancies, implying that future clashes would be linked to new situations forming in cities. Courbet’s brushstrokes, like the rocks, are rugged – harsher than one might expect for the mid-19nth century. This demonstrates that the artist’s approach to painting was a conscious critique of the flawlessly perfected, advanced Neoclassicist style that defined French painting in 1848.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““The Stone Breakers” Gustave Courbet – A History and Analysis.” Art in Context. January 4, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-stone-breakers-gustave-courbet/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 4 January). “The Stone Breakers” Gustave Courbet – A History and Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-stone-breakers-gustave-courbet/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““The Stone Breakers” Gustave Courbet – A History and Analysis.” Art in Context, January 4, 2022. https://artincontext.org/the-stone-breakers-gustave-courbet/.