“The Raft of the Medusa” Théodore Géricault – A Romanticism Analysis

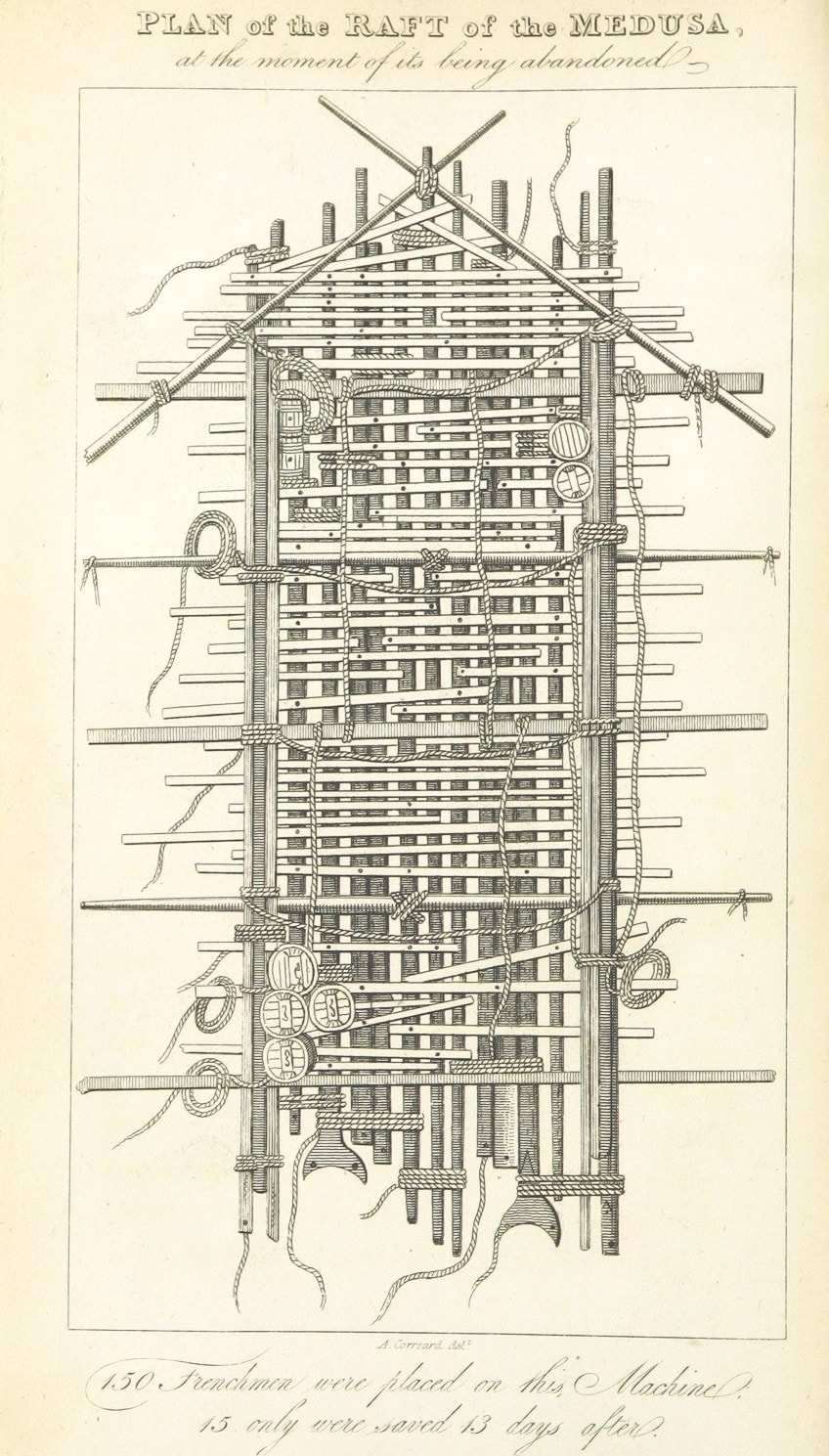

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault, currently located at the Louvre Museum, is regarded as a seminal work of French Romanticism. The Raft of Medusa painting portrays a scene that followed after the French naval ship Méduse‘s wreck, which went aground off the coastline of modern-day Mauritania on the 2nd of July, 1816. Following the incident, at least 147 individuals were abandoned on a hastily made raft; all but 15 perished in the 13 days until their retrieval, and those who managed to survive suffered from malnutrition and extreme dehydration, as well as cannibalism. The incident created international controversy, in part because the blame was generally ascribed to the French captain’s inexperience.

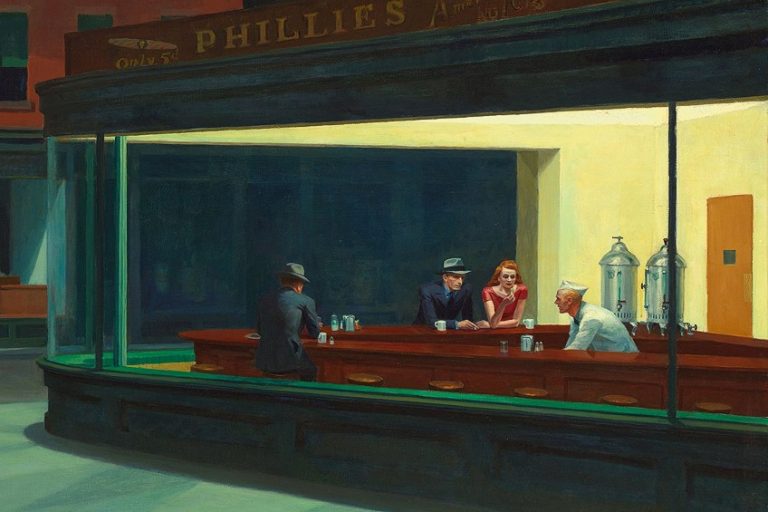

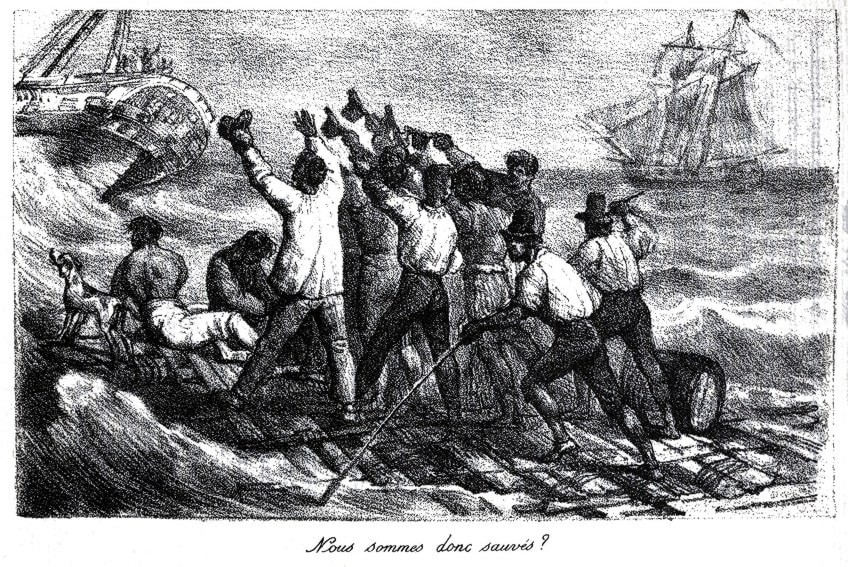

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault

Théodore Géricault opted to represent this event to commence his career with a large-scale uncommissioned piece on a topic that has already piqued the public’s curiosity. He was captivated by the occurrence, and before beginning work on the eventual painting, he conducted a considerable study and created several preparatory sketches. He spoke with two survivors and built a precise size replica of the raft. He went to hospitals and mortuaries to see the texture and coloration of the flesh of the ailing and dead in person.

| Year Completed | 1819 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 490 cm x 716 cm |

| Current Location | Louvre Museum, Paris |

An Introduction to Théodore Géricault

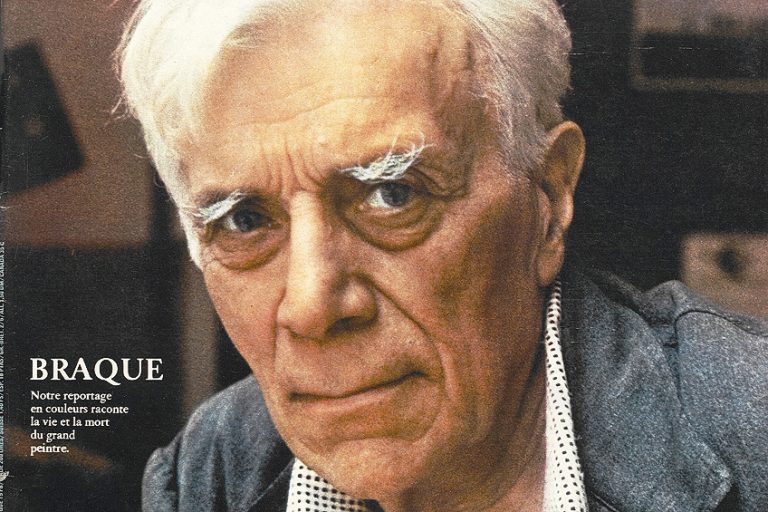

Before we get into the artwork itself, you may be wondering which artist painted the Raft of the Medusa. Géricault’s brief career had a significant effect on the development of modern art, particularly the growth of French 19th-century painting.

His revolutionary use of contemporaneous subjects, his merging of classical aspects with a moody, painterly aesthetic, his love of equines, his interest in sublime and horrendous topics, and his sympathy for society’s weak and helpless make him a peculiarly complicated artist, but one who helped pave the way for Romanticism’s focus on sentimentality and subjective experience.

The Raft of Medusa painting, his most renowned work, was a breakthrough event in the history of contemporary art since it combined the urgency of the latest issues and a firsthand sensibility with the conventional, massive framework of a major Salon painting.

In its focus on current events and the reality of the human condition, Gericault’s work was completely modern.

He drew dramatic events from real life on a grand scale, and as a draftsman, he found ideas in the most mundane topics. This is evident in his huge Raft of Medusa painting, as well as his lithographs of London’s impoverished and his portraiture of the mentally ill.

Despite learning from the Old Masters, notably Michelangelo, Géricault’s use of rapid, dynamic brushstrokes and opposing light effects generated evocative settings that broke loose from the polished Neoclassical school of painting.

Much of Gericault’s art exemplifies what we now call Romanticism, with its emphasis on the exotic, emotive, and sublime.

This might be understood as a reaction to David and Ingres’ earlier Neoclassicism, which represented Enlightenment ideas of structure and logic. The particular artist’s personal, emotional reaction is what matters for Gericault, an idea that would continue through into the 20th century.

Analyzing The Raft of Medusa Painting

The Raft of Medusa painting portrays a scene that followed after the French naval ship Méduse‘s wreck, which went aground off the coastline of modern-day Mauritania on the 2nd of July, 1816. But there is more to this story. Let us now look at a deeper analysis of this painting.

Contextual Background

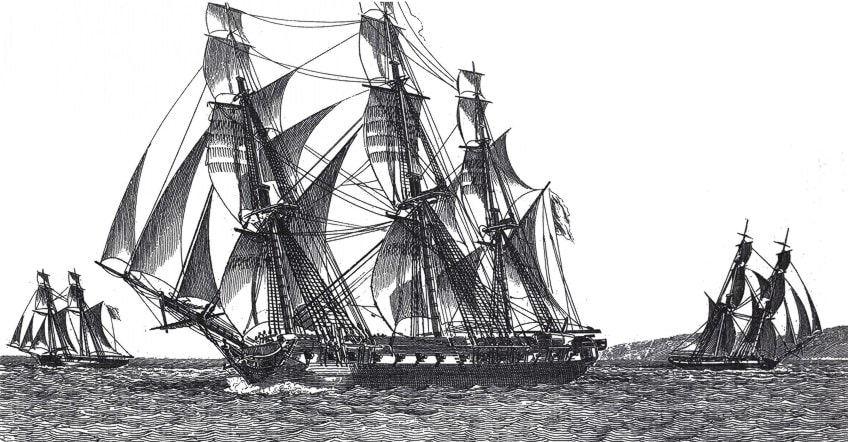

The French galley Méduse set sail from Rochefort in June 1816, heading for the port of Saint-Louis in Senegal. She led a company that included the Loire (a Storeship), the Argus (a brig), and the Écho (a corvette). While having barely sailed in 20 years, Viscount Hugues Duroy de Chaumereys had been named commander of the ship.

Following the disaster, popular outcry incorrectly assigned blame for his employment to Louis XVIII, despite the fact that it was a standard naval post made inside the Ministry of the Navy and much outside the monarch’s interests.

The purpose of the ship was to acknowledge the British surrender of Senegal as part of France’s approval of the Treaty of Paris. Colonel Julien-Désiré Schmaltz, the newly elected governor of Senegal, and his wife and family were counted among the passengers aboard the ill-fated ship.

The Méduse surpassed the other ships in an attempt to make up time, but due to inadequate navigation, it wandered 160 kilometers off track. The ship ended up going aground on a sandbank off the West African coast, on the 2nd of July. The crash was generally blamed on De Chaumereys’ ineptitude, a returning émigré who clearly lacked the necessary experience and skill but had been awarded his appointment as a consequence of political favoritism.

After attempts to liberate the ship proved unsuccessful, the terrified crew and passengers embarked on a 100-kilometer journey to the African shore in the frigate’s six small vessels on July 5.

Despite the fact that the Méduse could carry 400 passengers, including 160 crew members, the boats could only hold roughly 250. The balance of the ship’s capacity, as well as half of a detachment of marine infantrymen, were destined for Senegal.

A minimum of 146 men and one woman were crammed aboard a hurriedly constructed raft, which was partly submerged once loaded. 17 crew members chose to remain on board the stranded Méduse. The captains and crews on the other vessels intended to pull the raft, but after only a few kilometers, the raft was abandoned. The raft’s crew had just a bag of ship’s biscuit (devoured on the very first day), two barrels of water (dropped overboard during battle), and six casks of alcohol.

The boat took the survivors “beyond the limits of human experience”.

Crazed, dehydrated, and hungry, they massacred mutineers, ate their dead colleagues, and slaughtered the weakest. After 13 days, on the 17th of July 1816, the raft was retrieved by happenstance by the Argus – no special search attempt was undertaken for the raft by the French. Only 15 men were alive at this point; the others having been slain or tossed overboard by their companions, died of famine, or thrown themselves into the water in hopelessness. The episode caused great public humiliation for the French monarchy, which had only recently been returned to power following Napoleon’s defeat in 1815.

Description

The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault depicts the exact moment when the surviving 15 last survivors, following 13 days of being lost afloat the ocean on the raft, see a ship arriving on the horizon. The piece is set at a point when “the devastation of the raft may be regarded to be finished,” according to a British critic. The artwork is a monumental size of 491 cm by 716 cm, so the majority of the characters are life-sized, and those in the front are nearly twice life-size, pressed close to the image plane and pushing upon the observer, who is brought into the physical activity as a participant.

The improvised raft is depicted as scarcely seaworthy as it rides the heavy waves, while the men are depicted as shattered and despondent. Another old guy pulls his hair out in despair and defeat as he clutches his son’s body at his knees. A smattering of bodies litters the foreground, ready to be washed away by the raging waves. The men in the center have just seen a lifeboat; one points it out to another, and an African member of the crew, Jean Charles, stands atop a barrel and furiously waves his scarf in an attempt to attract the ship’s notice.

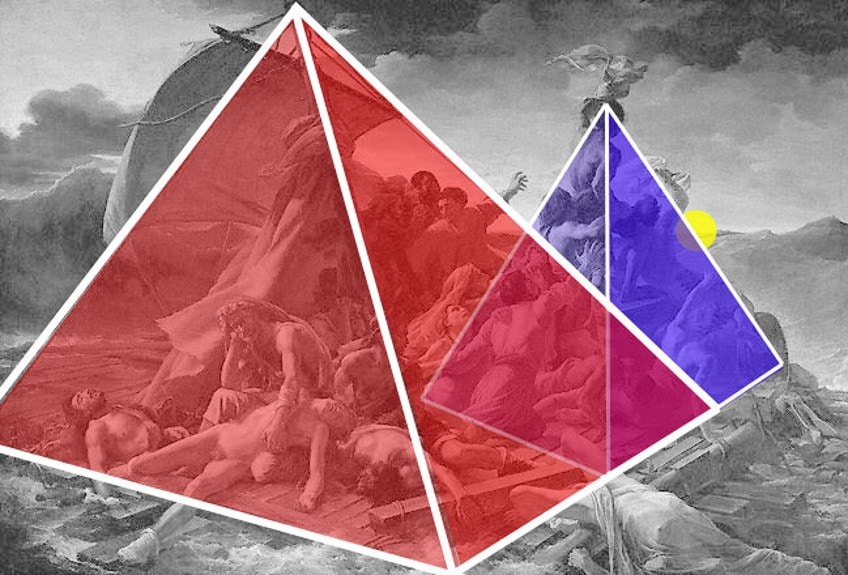

The painting’s graphic arrangement is built around two pyramids. The first is formed by the perimeter of the huge mast on the canvas’s left side. The front horizontal collection of dead and injured persons serves as the foundation from which the survivors emerge, rising upward into the emotional apex, where the focal figure urgently waves at a rescue craft.

The viewer’s gaze is pulled to the center of the painting, then to the directional movement of the survivors’ bodies, seen from behind and stretching to the right.

From the deceased at the lower left to the living at the top, we are led by a single horizontal diagonal beat. Two more diagonal lines are employed to increase the tension and drama. The first traces the mast and its scaffolding and directs the viewer’s gaze to an incoming wave that promises to swallow the raft, while the second, formed of reaching figures, directs the viewer’s gaze to the faraway outline of the Argus, the ship that finally saved the survivors.

Géricault’s palette consists of delicate flesh tones as well as the muddy colors of the survivors’ clothing, the water, and the clouds. Generally, the painting is gloomy and focuses heavily on the use of dismal, predominantly brown hues, which Géricault thought was successful in portraying tragedy and agony.

The lighting of the piece has been characterized as “Caravaggesque,” after the Italian painter who was intimately identified with tenebrism—the use of extreme juxtaposition between light and shade.

Even Géricault’s portrayal of the water is subdued, with darker green hues used instead of the darker blue tones that could have provided a juxtaposition with the tones of the raft and its people. A brilliant light emanates from the far region of the rescue craft, illuminating an otherwise dark brown terrain.

Execution

Géricault was attracted by reports of the well-publicized 1816 shipwreck and realized that depicting the incident may help him build his career as a painter. After deciding to proceed, he conducted a significant study before beginning the painting. He encountered two survivors in early 1818: Henri Savigny, and Alexandre Corréard at the École nationale supérieure d’arts et métiers.

The atmosphere of the final picture was heavily influenced by their emotive recollections of their experiences.

Georges-Antoine Borias, an art historian, claims that “Géricault set up his studio across the street from the Beaujon hospital. And so started a somber decline. He poured himself into his task behind closed doors. Nothing frightened him. He was both feared and shunned.” Géricault’s previous trips had introduced him to sufferers of madness and disease, and when studying the Méduse, his desire to be historically exact and genuine led to a fixation with corpse rigidity.

To accomplish the most accurate rendition of the skin tones of the deceased, he sketched bodies in the Hospital Beaujon mortuary, analyzed the human face of dying patients, decided to bring dismembered appendages back to his workshop to study their deterioration, and ended up drawing a decapitated head loaned from a mental asylum and saved on his workshop ceiling for a couple of weeks.

He collaborated with Corréard, Savigny, as well as another victim, craftsman Lavallette, to create an authentic scale replica of the boat, which was recreated on the completed painting, even displaying the gaps between some of the boards. Géricault posed models, gathered research, copied important works by other painters, and traveled to Le Havre to study the water and sky.

Despite having a fever, he went to the seaside several times to watch storms break on the coastline, and a trip to painters in England provided another chance to study the environment while traversing the English Channel. He created and painted various preliminary sketches while determining which of several different catastrophic scenes to represent in the final painting.

Géricault’s creation of the painting was slow and laborious, and he battled to choose a single graphical successful moment to best convey the intrinsic intensity of the event.

Among the situations he studied were the soldiers’ rebellion on the second day on the raft, cannibalism only after a few days, and the evacuation. Géricault eventually settled on the scene described by one of the victims, when they first noticed, on the skyline, the coming rescue ship Argus – shown in the top right of the picture – to which they sought to signal. The ship, on the other hand, went past.

“From the intoxication of delight, we plummeted into tremendous sorrow and despair,” one of the surviving crew members said.

Exhibition and Reception of the Raft of Medusa Painting

The Raft of Medusa painting was initially presented at the 1819 Paris Salon under the title Shipwreck Scene, despite the fact that its true topic would have been obvious to modern visitors. Louis XVIII funded the show, which included almost 1,300 paintings, 208 sculptures, and several more engravings and architectural drawings.

The exhibition’s headliner was Géricault’s painting, which “strikes and captures all eyes.” “Monsieur Géricault, you’ve portrayed a catastrophe, but it’s not one for you,” Louis XVIII had stated three days before the opening.

Géricault had purposely intended to be both socially and aesthetically antagonistic. Critics reacted to his strong attitude in kind, with either repulsion or acclaim, depending on whether the writer sympathized with the Bourbon or Liberal position. The artwork was widely regarded as being supportive to the people stranded on the raft, and hence to the anti-imperial cause championed by the surviving Corréard and Savigny.

The inclusion of a black person at the composition’s apex was a contentious representation of Géricault’s abolitionist views. Christine Riding, an art critic, believed that the artwork’s later display in London was timed to correspond with anti-slavery protests in the city.

Géricault’s picture, according to art historian and curator Karen Wilkin, is a “jaded condemnation of the blundering misconduct of France’s post-Napoleonic politicians and officials, most of which was drawn from the remaining families of the Ancient Régime.” The artwork mainly attracted viewers, yet its subject matter repulsed many, depriving Géricault of the popular success he had hoped for.

The artwork was given a gold medal by the panel of judges at the end of the show, but it did not receive the higher honor of being selected for the Louvre’s national inventory. The Raft of the Medusa by Théodore Géricault was advocated by the Louvre’s curator, Comte de Forbin, who acquired it from Géricault’s heirs following his death in 1824. The artwork has now taken over the gallery in which it is shown. According to the display description, “the sole hero in this moving narrative is mankind.”

That concludes our look at “The Raft of the Medusa” by Théodore Géricault. Currently located at the Louvre Museum, this painting is regarded as a seminal work of French Romanticism. The incident created international controversy, in part because the blame was generally ascribed to the French captain’s inexperience.

Take a look at our Raft of Medusa painting webstory here!

Frequently Asked Questions

Which Artist Painted the Raft of the Medusa?

Théodore Géricault’s short career had a considerable impact on contemporary art development, notably the expansion of French 19th-century painting. His revolutionary use of contemporary subjects, his blending of classical elements with a moody, painterly aesthetic, his love of equines, his interest in sublime and horrifying subjects, and his sympathy for society’s weak and helpless make him a peculiarly complicated artist, but one who helped pave the way for Romanticism’s emphasis on sentimentality and subjective experience. His most famous work, The Raft of Medusa, was a watershed moment in the history of modern art because it united the immediacy of current events and a direct sense with the traditional, huge framework of a great Salon painting.

What Was the Raft of Medusa Painting About?

The Raft of Medusa painting represents a situation that transpired when the French naval vessel Medusa was destroyed when it went aground off the coastline of Mauritania on July 2, 1816. After the occurrence, at least 147 individuals were left stranded on a hastily built raft; all but 15 perished in the 13 days it took to discover them, and those who did survive endured starvation, extreme dehydration, and cannibalism.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““The Raft of the Medusa” Théodore Géricault – A Romanticism Analysis.” Art in Context. January 13, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-raft-of-the-medusa-theodore-gericault/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 13 January). “The Raft of the Medusa” Théodore Géricault – A Romanticism Analysis. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-raft-of-the-medusa-theodore-gericault/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““The Raft of the Medusa” Théodore Géricault – A Romanticism Analysis.” Art in Context, January 13, 2022. https://artincontext.org/the-raft-of-the-medusa-theodore-gericault/.