“The Dance” Matisse – Analyzing Matisse’s Dancing Circle Painting

The Dance by Matisse was produced in 1910 for Sergei Shchuken, a businessman from Russia. Matisse’s The Dance features a dancing circle of figures and is regarded as a highlight of the artist’s career in the further advancement of contemporary art. It is not the first Dancers painting and was preceded by a preliminary version which has been titled Dance (I) (1909). It was followed by the triptych mural titled The Dance II in 1932.

Table of Contents

The Dance by Matisse

Henri Matisse was fascinated by the notion of dancing and the potential to be moved by music. This curiosity became a recurring theme in Matisse’s artworks. Despite this, his Dancers painting did not earn the acclaim it has today when it was originally presented. In this article, we will try to comprehend a picture full of smart references so that we may better appreciate the actual spirit of the Matisse Dancers.

But who was the artist behind the famous dancing circle painting? Let us first commence with a short introduction to Matisse himself.

A Brief Introduction to Henri Matisse

| Nationality | French |

| Date of Birth | 31 December 1869 |

| Date of Death | 3 November 1954 |

| Place of Birth | Nice, France |

Henri Matisse is typically acknowledged as the most outstanding colorist of the 20th century, rivaling Pablo Picasso in regards to the significance of his innovation. He was a post-Impressionist who grew to recognition as the head of the French movement Fauvism. Despite his fascination with Cubism, he eschewed it in favor of using color as the cornerstone for expressive, ornamental, and very often monumental canvases.

He once said, dubiously, that he wanted to produce work that would have “a soothing, relaxing effect on the psyche, somewhat like a nice couch.”

Still lifes and the naked human form were beloved subjects all throughout the span of his lifetime; North Africa would also prove to be a key influence; and, at the end of his life, he made a significant addition to collage art with a set of pieces utilizing color cut-out forms. He was also a well-known sculptor.

In Matisse’s Fauve artworks, he applied only pure hues and the white of uncovered canvases to generate an environment that was filled with light. Matisse employed opposing sections of pure, unmodulated color to add dimension and form to his paintings rather than utilizing shading or modeling. These concepts remained significant to him throughout his tenure.

Matisse’s artwork was highly influential in spreading the importance of ornamentation in contemporary art.

Despite often being considered an artist committed to bliss and a sense of satisfaction, his application of patterns and colors is quite often disorienting and frightening. Matisse’s line drawings and paintings were highly inspired by various civilizations’ art.

Matisse reportedly stated that he intended his work to be one of “harmony, purity, and tranquility free of disturbing or gloomy subject matter,” and this ambition influenced those, such as Clement Greenberg, who turned to art to give refuge from the confusion of contemporary life. Matisse’s artwork was centered on the human body. He shattered the figure violently at times, while at others he treated it almost as a curved, ornamental feature. Some of his art reflected his subjects’ moods and personalities, but more often than not, he utilized them as vessels for his own sentiments, reducing them to ciphers in his massive works.

After witnessing many displays of Asian art and going to North Africa, he blended some of the decorative aspects of Islamic art, the angular forms of African sculptures, and the flattening of Japanese prints into his own approach.

In the 1950s, scholars saw Matisse and Fauvism as forerunners of Abstract Expressionism and most of contemporary art.

Some Abstract Expressionists, such as artist Lee Krasner, are influenced by Matisse’s many mediums; his paper cut-outs inspired her to slice apart and recreate her own works. Color field artists like Kenneth Noland and Mark Rothko were drawn to his large fields of intense color, as shown in the Red Studio (1911).

In contrast, Richard Diebenkorn was more concerned with how Matisse generated the perception of depth and the spatial friction between his subject matter and the flat canvas. Many, like Robert Motherwell, did not immediately demonstrate Matisse’s impact in their works but were impacted by his perspective on color and form in painting.

Matisse’s The Dance Paintings

Matisse’s artworks frequently incorporated themes such as music and dance. Three of these paintings share the title The Dance, although the first one was a preliminary version and The Dance II was a mural. We will be touching on the first Dancers paintings, but focusing on the last two.

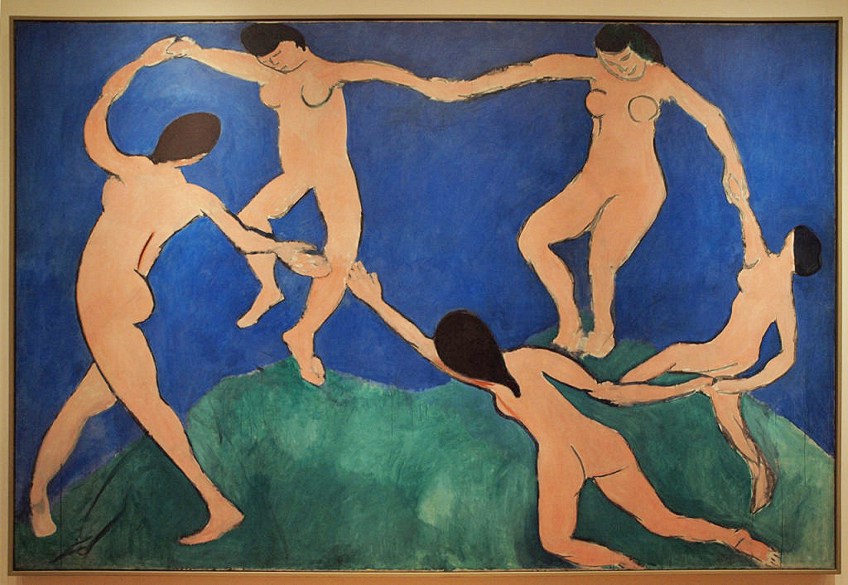

The Dance (1910)

| Title | The Dance |

| Date Created | 1910 |

| Medium | Oil on Canvas |

| Dimensions | 260 cm x 391 cm |

| Current Location | The Hermitage, St. Petersburg |

Matisse created an early version of this piece, known as Dance (I), in March 1909. It’s a compositional exercise with lighter colors and fewer details. The work was highly esteemed by the painter, who once described it as “the overwhelming peak of brilliance”. Dance is a big ornamental panel produced in conjunction with a counterpart piece, Music (1910), for the Soviet industrialist and art connoisseur Sergei Shchukin, with whom Matisse had a long acquaintance.

This picture, together with “Music”, hung on the stairway of Shchukin’s Moscow residence until the October Revolution in 1917.

The image depicts five dancing individuals in bright red against a simple green background and a beautiful blue sky. It recalls Matisse’s early interest in artwork and employs a traditional Fauvist color palette: the strong warm colors against the green-blue backdrop, as well as the syncopated sequence of dancing figures, communicate ideas of emotional liberty and decadence. The picture is frequently connected with Igor Stravinsky’s famous 1913 musical composition Dance of the Young Girls.

When Shchukin ordered Matisse to create this picture, he specifically requested that the dancers be costumed. Matisse’s decision to represent them naked was sensational when he displayed it at the Autumn Salon in Paris. Some even accused him of suffering from a mental ailment. Their artist/patron connection was strained as a result of this predicament.

Eventually, the two agreed that the dancers might be represented naked, but no genitals would be overtly portrayed.

The Dance is really a zoomed-in rendition of a section of Matisse’s 1905 artwork The Joy of Life. It is historically significant, particularly in terms of the emergence of the Fauvist movement. Matisse was inspired to create this painting after witnessing field laborers dancing on a seashore in the south of France.

The figures seem to revolve in a circular motion in both artworks. Matisse, on the other hand, includes just five figures in his circle in The Dance, rather than six. Their physical parts are reduced, making them appear non-binary, with neither female nor male features. Their skin tone is likewise uniformly tanned.

The picture is vast, yet even at these dimensions, the framing is too small for the figures’ stature.

Matisse had to make an arch on some of their backs in order for them to fit completely within the frame. As a result, their circular aspects draw the audience’s eye: the characters on top are curled as if arching their backs, while those on the bottom are extended. Their curves dominate the picture, and their circular form, created by interlocking hands, gives the painting a sense of movement and momentum.

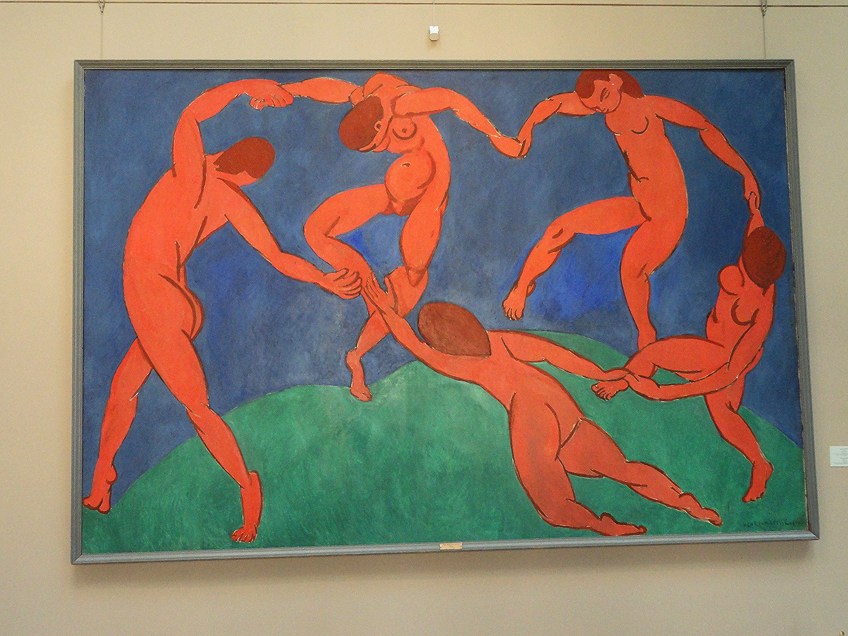

The Dance II (1932)

| Title | The Dance II |

| Date Created | 1932 |

| Medium | Mural |

| Dimensions | 4 m x 13 m |

| Current Location | Barnes Foundation |

Matisse also created a similar Dancer painting, the mural The Dance II. The mural was to be installed over three arches that span the windows of Barnes’ gallery’s main hall. Matisse completed the mural at Nice, France, using canvas given by Barnes, rather than on-site. This was an uncommon technique for such a piece, but the benefactor had given him an unlimited artistic license, and working onsite would have been impracticable in any case.

The endeavor was challenging for Matisse, and it ended up taking him two years, leaving him physically and emotionally exhausted. He was also deeply upset to learn, during the installation, that Barnes had no plans to show the piece to the public. Nonetheless, Matisse was ecstatic about the piece. Matisse wrote:

“It has a magnificence that one can only imagine until one sees it, for the entire roof and its arched vaults spring to life via radiation, and the primary impact runs all the way down to the floor… I’m quite weary yet overjoyed. When I watched the painting being hung, it divorced from me becoming a part of the structure.”

Some critics believe that The Dance II mural was significant in allowing Matisse to reconnect to the most fundamental foundations of his painting. For Matisse, the piece emphasized features such as simplicity, flattening, color focus, and the use of paper cut-outs, all of which would eventually play an essential part in his creative evolution. Barnes granted Matisse complete creative freedom in terms of subject matter; the agreement only defined the size of the mural and its location on the southeast wall of the Main Gallery.

Matisse appears to have chosen the dancing topic early on.

The Barnes Foundation provided him with the chance to retake his place as a prominent figure in the decorative mural art heritage, and to do so publicly and on a huge scale. The Foundation’s Main Gallery featured some of the most significant paintings of the second half of the 19th century in 1930; they, too, would present the artist with both a task and a possibility. Matisse’s difficulty was to locate himself within the French heritage of decorating while proclaiming his work as avant-garde.

The use of dance as a motif, namely the representation of eternal nudes moving in a circle, not only recognized classical heritage but also allowed him to illustrate the continuation of his own works. Decorations were large-scale paintings created to fit into a specific context, such as a private room or a place in a public institution. Matisse’s artistic output was driven by a decorative method of painting and thinking.

Matisse sought for a picture whose shape is tensile and extending rather than closed and united, and whose surface consists of broad zones of flat colors that defy the conventional sense of depth and its appeal to patient contemplation.

Instead, the colors extend beyond the canvas’s four edges, immersing the viewer in a dynamic sensory experience. It was obvious from the start that creating an acceptable design for the area where The Dance would hang would be tough. The mural was supposed to cover a large area on the southern wall of the Main Gallery, over three French doors and beneath the curved arches of the roof. The area is divided into three semi-continuous lunettes by two pendentives that drop down.

Matisse proceeded to Nice to start work on the mural after finalizing the arrangement, arriving in mid-January 1931. He began by renting a vacant garage in which he could work to scale. Matisse started to paint the canvases at some point during this procedure. He liked to work straight on the canvas, with minimal previous detail research, but he ran into a problem: the mural was too vast to accommodate alterations. To remove paint with a turpentine-soaked rag, or to cover up an earlier stage, was a considerably larger undertaking than with a little easel painting.

He was also almost 60 years old, and the task of creating the pattern repeatedly had fatigued him.

As a result, he devised a design method based on paper cutouts: rather than painting directly on the canvas, he cut out colorful paper and attached it to the surface of the unfinished, partially painted mural. All of Matisse’s previous sketches and color explorations were now laid aside, and he began over. He understood what he intended to achieve this time and worked considerably quicker. He laid down three canvases and sketched in the new group of dancers after double-checking his measurements.

In addition, he modified the composition. Where he had previously constructed a continuous plane of movement, he now separated the work into three points of interest—possibly in reaction to the recalculated size of the pendentives, which were now twice as broad as in the previous plan. He also expanded the number of figures from six to eight, placing two dancers for each of the three lunettes and introducing a pair of goddesses, one beneath each of the pendentives, to serve as a bridge from one lunette to the next.

This impression of expansion, fracturing, and motion was intended to engage the observer in active, active interaction with the adjacent room’s environment.

Matisse claimed that the black grounds of the panels continued the region between the doors, producing the illusion of a “monumental foundation for the vault.” The dark also contrasted with the regions of brilliant light that entered the space through the French doors. The gray figures were meant to represent the stone of the adjacent architecture, while the blue and pink were meant to recall the sky just above the landscape viewable through the doors. The color chord also included the green of the grass, trees, and plants.

Matisse Dance Analysis

Henri Matisse’s artistic choices for this painting generated quite a stir in the art salons of 1910; the brazen nakedness and clumsily placed colors gave the artwork a primal aspect that some observers perceived as barbarous. Matisse depicted this celebration in only three colors: blue, green, and red. These three vibrant colors provide a dramatic contrast, in keeping with Fauvism’s traditional color connotations. According to an art critic who observed Matisse producing the painting in his workshop, “the colors were pure from the tubes.”

Because of the economy of design and detail, the figures are unclear; neither their facial expressions nor gender is easily identified. Against the blue and green backgrounds, red-hued silhouettes are simply contoured with thick curves. Matisse investigated the interaction between colors and lines in order to achieve harmony; colors, for him, were not designed to operate in isolation.

Furthermore, there are no structural or landscape aspects to generate a feeling of scale or perspective. The large canvas features a fairly flat background, with the dancing people as the main focal point.

The Fauves shared the primitivists’ curiosity in indigenous tribes, and primitivism motivated them to produce art that reverted to the spirit of creation and communion. The coarsely sketched figures in dance recall primitivist aesthetics, and the subject matter, individuals communing within an empty, maybe “virgin” terrain, might be understood as an advocate for a required reunion with nature. The nakedness of the figure, for example, symbolizes a rejection of contemporary society.

The artwork is transformed into a symbol of oneness between humanity, heaven, and nature. Matisse’s goal was to produce a synthesis of primitivism; the awkward forms inspired by rudimentary and folk art, as well as the brilliant, lively colors, reflected instinct and environment. Individuals are completely absorbed in their dancing, indifferent to any everyday duties or employment.

Matisse focuses on the movement and rhythm created by the dancers more than their unique look. The dance is the greatest emblem of individual reunion.

The five characters are walking hand in hand in a ring, but on the left, we can see that the two persons’ hands are divided; they brush against each other rather than holding. Matisse, on the other hand, deliberately placed the rupture where it covers the other figure’s leg so as not to disrupt the harmony of the colors and circle. Because the point of the rupture is closest to the viewer’s location, it might be taken as an invitation to engage in the dance.

The circle comes to identify those who “are outside,” and so to bring people together. Matisse’s dancers are in a similar situation to those in The Joy of Life’s backdrop. The theme piqued Matisse’s interest sufficiently for him to isolate it and devote a whole painting to it. Nonetheless, based upon the research of Charles Caffin, Matisse’s obsession with dancing began at the Moulin de la Galette, where he would watch folks dance. This sort of popular dancing contrasts with more formal, conventional, or classical dance forms such as ballet. The Dance, in this way, provides a commentary on the development of dance.

Despite the painting’s simple manner, Matisse managed to capture a feeling of movement and space in Dance: the boundless sky and rounded curves that comprise the ground appear to be imbued with part of the energy radiating from the rhythmically charged bodies. The characters appear to be in a trance, and the observer can practically hear the pounding of the drums and picture a furious dance as they whirl in a circle. Because music provides rhythm, the articulation of dance with the music is crucial.

In this sense, it is intriguing to compare Dance to its equivalent Music. Dance’s continuous movement contrasts sharply with Music, where the subjects are motionless. The vocalists nearly appear to be spectators, staring up at the dancers while laying their arms on their knees.

That concludes our look at “The Dance” by Matisse. Matisse’s “The Dance “depicts a dancing circle of individuals and is recognized as a high point in the artist’s career as well as the growth of modern art. It is not the first “Dancers” painting, although it was preceded by a preliminary version titled “Dance” (I) (1909). In 1932, it was followed by “The Dance II”, a triptych mural.

Read also our matisse the dance web story.

Frequently Asked Questions

What Is an Example of Matisse’s Line Drawing?

There was a lot of overlap between Henri Matisse’s paintings, sketches, and cut-out artworks. When looking at this artist’s techniques of creation, you might argue that it makes more sense to look at it as a whole rather than breaking it down into different mediums. An example of Matisse’s line drawings is Vase de Fleurs (1944).

Can You Give a Brief Matisse Dance Analysis?

Matisse’s Dancers painting used only three hues to express this celebration: blue, green, and red. In line with Fauvism’s typical color implications, these three bright hues make a dramatic contrast. “The colors were fresh from the tubes,” said an art critic who saw Matisse working on the painting in his workshop. The figures are obscure due to the economy of design and detail; neither their facial expressions nor gender is clearly determined.

Alicia du Plessis is a multidisciplinary writer. She completed her Bachelor of Arts degree, majoring in Art History and Classical Civilization, as well as two Honors, namely, in Art History and Education and Development, at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. For her main Honors project in Art History, she explored perceptions of the San Bushmen’s identity and the concept of the “Other”. She has also looked at the use of photography in art and how it has been used to portray people’s lives.

Alicia’s other areas of interest in Art History include the process of writing about Art History and how to analyze paintings. Some of her favorite art movements include Impressionism and German Expressionism. She is yet to complete her Masters in Art History (she would like to do this abroad in Europe) having given it some time to first develop more professional experience with the interest to one day lecture it too.

Alicia has been working for artincontext.com since 2021 as an author and art history expert. She has specialized in painting analysis and is covering most of our painting analysis.

Learn more about Alicia du Plessis and the Art in Context Team.

Cite this Article

Alicia, du Plessis, ““The Dance” Matisse – Analyzing Matisse’s Dancing Circle Painting.” Art in Context. February 17, 2022. URL: https://artincontext.org/the-dance-matisse/

du Plessis, A. (2022, 17 February). “The Dance” Matisse – Analyzing Matisse’s Dancing Circle Painting. Art in Context. https://artincontext.org/the-dance-matisse/

du Plessis, Alicia. ““The Dance” Matisse – Analyzing Matisse’s Dancing Circle Painting.” Art in Context, February 17, 2022. https://artincontext.org/the-dance-matisse/.